After doing an audience analysis, selecting a topic considering the audience’s needs and interests, and creating the thesis, we need to develop the body of the speech. The body is the largest component of the speech, about 85 percent, and where we actually do what the thesis says. In the body, the speaker gives the information or arguments necessary to fulfill the intention of the thesis.

|

“Writing” a Speech

When a student says, “I’m going to write my speech,” we cringe. The way we use language is different when spoken versus when written. Inevitably, if a student sits down to write a speech, they will slip into a written style of language, like they are writing a paper for class. However, when this written speech is presented orally, it will sound dull, awkward, and artificial; it will sound like someone reading a paper for class. Instead, we develop or create speeches. We work from outlines to plan the flow of ideas and to keep the oral style of language. Avoid writing out any more than necessary to keep the speech in a conversational style of language.

Read more about the differences between speaking and writing. |

Most commonly, speeches are broken into 2-4 main points. Main points are the major subdivisions of the thesis. Having too many main points can be overwhelming to the audience; fewer main points are more manageable for the speaker and the listener. Imagine hearing a speaker say, “Today I want to review 14 types of financial aid.” Chances are most audience members would feel a sense of dread over how long they assume the speech will be. If, however, that speaker groups those 14 types into 4, saying “Today I want to review four categories of financial aid,” most would find the thesis far less overwhelming.

Coordination and Subordination

|

Main points have two key issues. First, the main points are coordinate with each other. The main points are of relatively equal importance, justifying them being set off as separate points. Second, each main point is part of the thesis, and once they are addressed, they fulfill the thesis. The main points are subordinate to the thesis; they fit within it and are part of it.

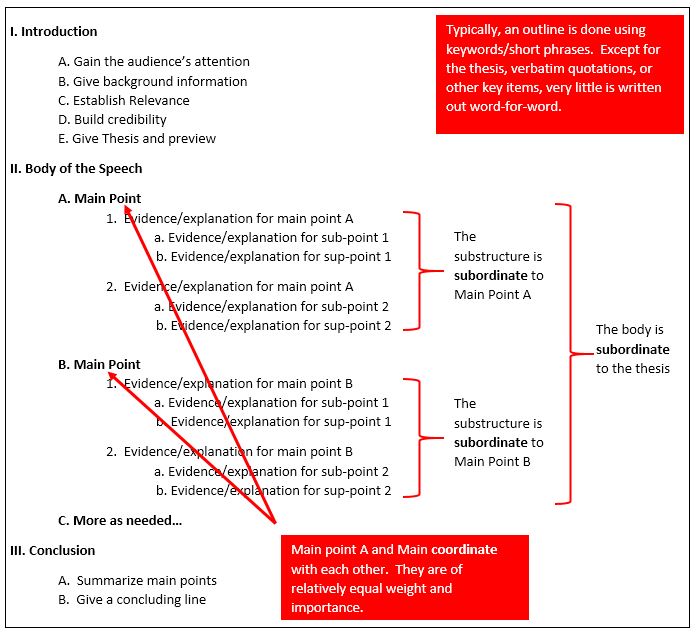

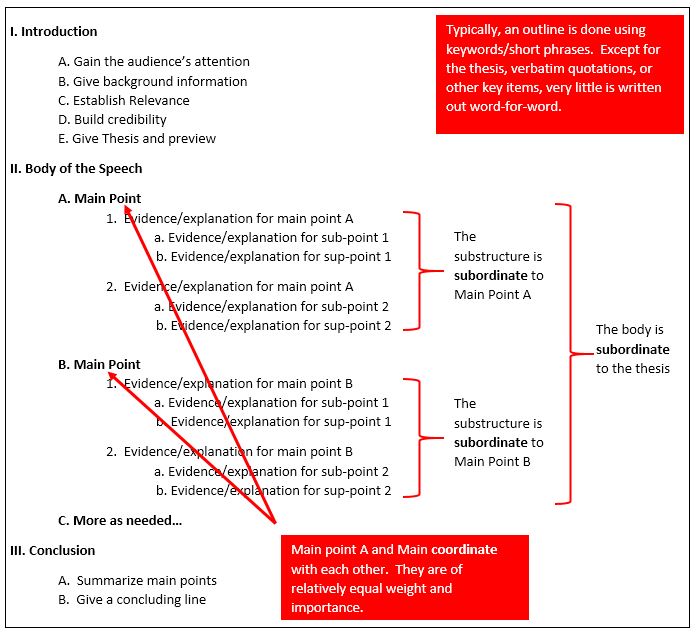

Image 1 is a generic sample of an outline demonstrating coordination and subordination. There are many different formats for outlines, so be aware that specific expectations for instructors will vary.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Figure 1

|

Organizing the Main Points

|

When developing the speech, an important step is to decide the order in which to present the main points. Speakers need to remember although they will have a thorough understanding of the content, they need to stop and think what will work well with the given audience. Just because the speaker is well versed in the information does not mean the audience will understand it clearly, unless the speaker presents it in a well-planned structure based on the audience’s needs.

Clear organization is important for three reasons:

- It makes the information much more memorable for the audience. To remember information, we need it organized, and it is up to the speaker to provide the organization.

- It reduces the chance of the audience getting lost or confused. Once they are lost, it is very hard to get the audience back on track. Creating confusion is easy; reducing confusion is difficult.

- A well-organized speech is easier for the speaker to better recall the order of the ideas to be presented.

In ordering the main points, use a logical idea development pathway. The speaker considers which order of presentation will be most effective with the audience in leading them to an understanding of the material. There are no concrete rules about what does/does not work because it depends on the topic and audience, but there are some common ways to do this:

- Present the information chronologically. For a process speech, take us through it in time-order, e.g., first step, second step, etc.

- Present the information spatially. In describing a place, take us through it by location. For example, if describing vacation opportunities in Minnesota, dividing the state into southern, central, and northern Minnesota provides structure to the information.

- Present the information topically. Divide the speech into major subtopics, and order them in a logical pattern. Start from specific and go broad, or start broad and move to specifics. To inform about financial aid, perhaps start with the most common to the least common. Or for a speech on iPads, the speaker might begin with what an iPad is and how it developed, then on to the ways students are using them, and then look at some unique and different ways iPads are being employed.

- Use a problem/solution format. Show us the problem being addressed, and then lay out the solution that is being used or advocated. The problem/solution format is commonly used in persuasion. For example, if a student wants to argue that college textbook prices are too high, they might first explain why they are expensive, then offer an alternative to using traditional bookstore texts. The format can also be used for informative speaking if the purpose of the speech is to discuss a problem and how it was solved, not advocating a solution, just telling us about what others did.

- Use a cause/effect format. For speeches attempting to show two things are linked causally, tell us about the causes and the impacts of those causes. This can be used in either informative or persuasive speaking. For example, a speaker could inform an audience on how caffeine affects memory by discussing how caffeine works chemically and then how it interacts with the body. For a persuasive speech, the speaker could attempt to persuade the audience that artificial sweeteners are bad for a person using the same structure; talk about how they work and how they impact the body.

Regardless of how the speaker orders the main point, the goal is always the same, move the audience along an idea development pathway that is logical, easy to follow, enhances memory value and understanding.

The substructure of the speech is the content included within each main point. The substructure contains the actual information, data, and arguments the speaker wishes to communicate to the audience. Within the substructure, the speaker must continue to determine the best order for items to be presented so the speaker and the audience can follow the development of ideas. This is the core of the speech. How to use evidence and sources will be addressed in a later section.

Incorporating Transitions

|

Transitions are a vital component of any good speech. Their role is to verbally move the audience from point to point, keep the audience on track, and to clearly lead the audience through the organization. It is important to have the audience on track from the start, and to keep them on track. If a reader gets lost, they can simply go back and re-read, but in speaking, if the audience gets lost, it can be very hard to get them back on track.

In public speaking, we like to use signpost transitions which are blatant transitions, such as “My second point is….” We are far less subtle in speaking than in writing.

There are five types of transitions we use in speaking:

"Today I will be telling you about some other forms of financial aid. I'll be looking at special scholarships, work reimbursement programs, and grants designed for individuals in special cases."

Note the thesis and the brief reference to the three main points. Another version of a preview is incorporated directly into the thesis. For example,

“Today I will tell you about three forms of financial aid you probably have not considered.”

Although not as detailed as the first example, it does let the audience know there are three main points to be covered. Regardless of which type is used, a key to a good preview is that it is not overdone, and merely mentions what is coming up. Do not over-preview.

- Thesis/Preview: This is a special transition used immediately after the thesis to preview the main points. Each point is briefly mentioned to let the audience know what is coming. For example,

- Single Words/phrases: These are general transition terms used throughout the speech, but mainly in the substructure. These include terms and phrases such as "also," "in addition to," "furthermore," "another," and so on.

- Numerical terms: Numbering is a common and very effective way to aid an audience in keeping track of a series of points. Terms such as "first," "second," and "third," can be very effective in clearly identifying major points. The major danger with these is their overuse. If a speaker uses numerical terms as transitions between main points, then uses them again in the substructure, the audience is likely to get confused.

“One type of alternative financial aid is special scholarships.”

“Another type of alternative financial aid is work reimbursement.”

“Another type of alternative financial aid is special grants.”

When heard back-to-back, they seem redundant. There will be discourse between the main point statements, so when they appear, they jump out as main point markers.

- Parallel Structure: Parallel structure is mainly used as main point transitions. The main point statements are worded very similarly. Once the audience hears the similarly worded statements, they know they are moving into a new topic. For example, referring to the earlier example, the three main points could be worded as:

- Summary/Preview: Summary/Preview transitions are an excellent choice for moving between main points. At the end of the main point, the speaker says one sentence in which the first half summarizes what was just covered, and the second half previews what is coming up. For example, "Now that we have looked at special scholarships, we can move on and consider reimbursements you can get from your workplace." This is a very distinct, clean, and effective transition. Also, by stating the focus of the next main point, the speaker can now move directly into the sub-structure of the main point.

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

Body of the Speech

Writing a speech versus Developing a speech

Main Points

Organization Patterns

Substructure

Transitions