1.3: Exploitation or Preservation? Your Choice! Digital Modes of Expressing Perceptions of Nature and the Land1

- Page ID

- 122271

Coppélie Cocq

© Coppélie Cocq, CC BY 4.0 http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0096.03

This chapter examines the role played by participatory media in environmental activism. The starting point for this study is the current debate on the exploitation of natural resources in Sweden’s Sámi region. When discussing this issue, different points of view about the environment are expressed. Some commentators believe that nature should be viewed as a commodity, while others perceive it as a heritage that must be protected. These views are expressed during demonstrations and in newspaper articles. They also circulate online in, for instance, Facebook groups, on Twitter, and through various blogs and YouTube uploads. They are articulated in posts and comments and voiced through music, short films, pictures, and posters. This chapter focussed on YouTube video clips, shedding light on how those who oppose mining depict nature and make their contribution to the environmental debate.

Perceptions of the environment differ according to cultural and social background. Sometimes nature is perceived as a commodity, something to be consumed. Sometimes it is seen as a heritage to preserve. As became evident in interviews conducted in a previous project,2 perceptions of nature and landscape, and an intimate relationship to the land, are experiences that are difficult to convey in words (Cocq 2014a, 2014b). This sense of ineffability is confirmed by the central role played by cultural workers in the debate about the Sámi land exploitation situation. Through fine arts, music, and performance, artists and cultural workers take a stance in the debate, adopting an indigenous, emic perspective. These initiatives contribute to the debate by raising questions about the rights of indigenous people, and by increasing the visibility of Sámi groups in rural areas.

This chapter will explore how visual and audiovisual participatory media can express, shape, and convey perceptions and understanding of nature — that is, perspectives that are difficult to communicate verbally in the public debate on environment and its exploitation. The study focuses on the relationship between media, culture, and society rather than on the use of media for the communication of meaning.

The increasing need to communicate emic perspectives on environmental and indigenous issues is met, and becomes visible through, an increased use of social and participatory media in, among other things, social movements. In contrast to traditional mass media, social media platforms are said to provide ‘prosumers’ (Olin-Scheller and Wikström 2010; Bruns 2008) due to easier modes of production, diffusion, and consumption.

The potential of social media for enabling marginalised voices to reach arenas they would otherwise not have access is the subject of much debate. As Saskia Sassen (2004) pertinently emphasises, social media are not isolated from social logic. Discourses of democratisation nuance the effects of new media on any larger political debate (O’Neil 2014). Critical voices suggest that social media, in fact, contribute to maintaining or even strengthening existing structures and power relations (Dean 2003; Fuchs 2010).

This study investigates how marginalised voices search for a venue in the media landscape. The case used as an example is that of the environmental movement’s resistance to the mining industry’s plans for the territory known as Sápmi. The movement is both local — it is concerned with Sápmi, the traditional area of the indigenous people of Europe — and global, insofar as it concerns indigenous rights and environmental struggle.

Mining Boom, Land Rights, and Perceptions of the Environment

Sápmi, the traditional area of Sámi settlement, comprises the northern regions of Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Russia. It is a heterogeneous area in terms of languages, livelihoods, and population. Discourses of decolonisation, cultural and linguistic revitalisation, and mobilisation for strengthening indigenous land rights are topics of immediate interest in contemporary Sápmi. In Sweden, this discourse is becoming increasingly prominent at the national level.

An increasing number of permits for exploration for minerals in Sweden has led to a ‘mining boom’. This, in combination with multiple types of exploitation (wind power, etc.) located in reindeer-herding areas, has led to a growing debate about the Swedish Minerals Act, as well as issues such as traditional land use, indigenous rights, mining, and growth in relation to what is termed majority society.

The summer of 2013 was a milestone for the mining resistance movement. That was when reindeer herders, various local actors, environmentalists, and others worked together to prevent a foreign exploration company from conducting exploratory drilling in Gállok (Jokkmokk municipality). From July to September 2013, a group of activists occupied the area in order to block the way for vehicles attempting to enter the prospection area. On several occasions there were confrontations with the police. Through demonstrations, art installations, and debates in social media, the protest movement brought national and international attention to the Gállok events.

Cultural variations in perceptions of the environment have been the subject of previous research. Such variations have been studied in a Sámi context by Rydberg, whose work shows how memories and language link the landscape to the identity of the Sámi in Handölsdalen sameby (administrative unit for reindeer herding; Rydberg 2011, 91–93). Conflicts between indigenous groups and international commercial interests elsewhere in the world have also been discussed, in terms of the spillover effects of globalization (e.g., Tsing 2005).

Previous research has also emphasised the need for the investigation of environmental issues in relation to human practices, representations, and behaviour (Nye et al. 2013; Evernden 1992) as well as ecological ethics (Plumwood 2002). The approach to nature as a construct and the rejection of the human-nature dichotomy open up the investigation of our practices, narratives, and understandings of the environment as modes of shaping, maintaining, and questioning representations.

Internet videos make it possible to combine different media materials. They disseminate images and movies — along with lyrics and music. This form of digital expression provides new tools that are being used strategically in activist movements. Social media have become a natural channel for activism, and the Web 2.0 has enabled increased communication, commitment, and coordination in activism. The effort to achieve ideological homogeneity is not the most interesting part of this development, but rather the efforts toward dialogue and understanding (Dahlberg 2007).

YouTube: A Channel for Environmental Activism

In order to investigate the use of participatory media in communicating nature, I have chosen two short films on YouTube as case studies. These films circulated in the summer of 2013, at the time of the Gállok conflict. YouTube was the platform that was used to publish videos and give an account of the ongoing struggle, for instance during interventions and clashes with the police. As part of the campaign against the mining industry, short clips were produced and published on YouTube.

The first YouTube video that concerns us was produced under the YouTube account name ‘whatlocalpeople’. ‘What local people?’ is the question that Clive Sinclair-Poulton, president of the British mining company, Beowulf Mining, asked at a presentation of one of its mining projects. The local people that he referred to, or rather questioned the existence of, were the people living in the area of Gállok (Kallak), located 45 kilometres outside Jokkmokk. Sinclair-Poulton’s question was rhetorical, and came as a response to a query about possible objections from the local population to a mining project.

The answer to Sinclair-Poulton’s statement came partly in the form of a website, http://www.whatlocalpeople.se. When we enter the website, we are met by a short movie showing Sinclair-Poulton’s presentation and statement, reinforced by a picture of clear-cutting (a forestry practice in which most or all trees are cut down within a given tract of forest). His question, ‘What local people?’ is followed, on the website, by an answer in the form of a series of portrait photographs — the faces of the people who live and work in the area, along with the text ‘We are the locals!’

Furthermore, the homepage contains tabs with which the web-visitor can navigate and find information about several mining projects in Sápmi. Under the tab ‘Vi finns’ [We exist], we learn about the website’s background:

The background for the creation of this website was anger. An anger caused by a statement made during an international mining conference in Stockholm. There, representatives of Beowulf Mining (Jokkmokk Iron Mines AB) presented their plans for mining of iron ore in an approximately 4.5 × 5 km large open pit in Gállokjávrre (known as Kallak), 50 kilometres west of Jokkmokk.3

Black and white photos are displayed at the head of the webpage — faces that demonstrate the existence of local people, satirising the manner in which Sinclair-Poulton used clear-cutting to illustrate the absence of a local population. The images used here emphasise the statement ‘Vi finns!’ [We exist]. ‘What local people’ is also the name of an exhibition, a YouTube account, and has become a slogan in the fight against exploration in the area around Gállok. It is also the title of a spoken-word poem by the artist Mimie Märak, performed at the site of Gállok.4

The video Vägvalet — för fast mark och rent vatten5 [Choice at the crossroads — for solid ground and clean water], the first example discussed in this chapter, was published by the whatlocalpeople account on 3 July 2013. The video does not mention any specific producer; it simply refers to the movement ‘whatlocalpeople’. This was at the beginning of the Gállok occupation, before the events got the attention of local, national, or international media. Almost two years later, the video again circulated in social media forums: on 13 February 2015, a post in the Facebook group Gruvfritt Jokkmokk [Mine-free Jokkmokk] linked to the video, maintaining that it was still of great interest, given the recent resolution from Sweden’s Mining Inspectorate referring the final decision on the Gállok mine project to the government.

Other YouTube video materials by whatlocalpeople include records of performances, speeches held at festivals, and demonstrations. Not least, it is this account that posted videos of confrontations with the police during the summer of 2013 in Gállok.6 These are the videos that attract the most viewers.

A short text introduces Vägvalet, a 2.30 minute long video:

En underbar värld eller feta nackars välde. Miljöbalk mot mineralstrategi. Vad väljer du?’ [A wonderful world or the empire of the ‘fat necks’. Environmental code against mineral strategy. What do you choose?]

Bli en del av den växande rörelsen [Become part of a growing movement]:

www.urbergsgruppen.se

www.whatlocalpeople.se

www.facebook.com/groups/ingagruvor

#Kallak

The clip starts with a quote from Dag Hammarskjöld, United Nations Secretary-General from 1953 to 1961 and a Swedish diplomat.

‘Din skyldighet är “att”. Du kan aldrig rädda dig genom “att icke”.’

[‘Your duty is “to”. You can never save yourself by “to not”.’]

The clip is introduced by the first two verses of the song ‘What a Wonderful World’ by Louis Armstrong. Images of forests, flowers and plants, mountain landscapes, birds, moose, and water are displayed on the screen. A banner at the bottom provides information about the Swedish Environmental Code (1998, 808), sustainability, and our responsibility to ‘administer nature’.

Fig. 3.1 Screenshot from Vägvalet (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=adJDdTw5AsQ)

Images of unpopulated natural areas are combined with the music to give a sense of harmony. About one minute into the movie, a voice interrupts Armstrong and the slideshow by shouting ‘Hallå?! Hallå?!’. This marks the beginning of the second part of the video. The music changes to the song ‘Staten och kapitalet’ [‘State and capital’] by the Swedish punk band Ebba Grön. This gives the slideshow a different tone. A banner with the text ‘test pit at Gállok (Kallak) July 1, 2013’ provides information about the images displayed, including a video of a great trench dug through the forest by machines. The text at the bottom of the screen now concerns the global demand for minerals. Headlines of news articles about the mining industry and its profits are shown in a collage, followed by images of machines and wide tracks dug into the ground, as well as of representatives of the government and the mining industry. Headlines of news articles appear again, this time referring to a possible environmental disaster, followed by pictures of an open mining pit.

The video ends with the words: ‘You can choose — your children and grandchildren cannot’. ‘Be part of an emerging/growing movement’ appears, with links to websites and Facebook groups. In the background, we hear voices shouting, as they do at demonstrations: ‘No mines in Jokkmokk’. In the last image, a text reads, ‘We believe in the future’.

Fig. 3.2 Screenshot from Vägvalet (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=adJDdTw5AsQ)

The video is divided into two parts, each representing contrasting and conflicting descriptions of the environment. The first illustrates the values of sustainability and responsibility, reinforced by text about the Swedish Environmental Code. The images connote harmony, showing wildlife, pristine nature, etc. The music is meant to reinforce the frame of harmony, hope, and celebration of life and the world. The video’s aesthetics anthropomorphise nature. This is a recurrent rhetorical strategy used in environmental discourse that has been proven effective in influencing people’s relation to nature, fostering conservation behaviour, and enhancing connectedness to nature (Tam et al. 2013).

The video’s second part stands in contrast to this, not least because of the abrupt break and change in the tone of images and sound. The focus is now on financial gain and the risks run by environment and population. The pictures show traces left in the landscape and images of politicians and mining companies. The music, the lyrics of which make a statement about government and capitalism, aims at inspiring anger. The voice heard at the beginning of the Ebba Grön song, which interrupts the middle of the film, functions as a wake-up call. The two perspectives are set out in contrast, placed next to each other in order to offer the viewer a choice: the one or the other. The title indicates that we have reached a ‘crossroads’ and that this is about the future (‘your children and grandchildren’).

The second video considered here is entitled Our land, our water, our future.7 It was produced and published by the photographer Tor Lundberg Tuorda on 19 December 2012. He has produced and published several videos on YouTube on the topics of the mining boom, the preservation of the environment, and responses to and actions against colonialism. He participates regularly in events related to the mining boom, including protest marches, and meetings. Tor Lundberg Tuorda is also active in academic circles. In an interview, he explains his work and the ambition behind his films:

The only thing I can do is to inform, to be stubborn. There is so much total madness in this. That’s what I do, it is the only power I have — with my camera as a weapon.8

Other films by Lundberg Tuorda include the recent ‘The Parasite’,9 about Swedish colonisation. His works have been screened in various contexts. His short film Mineralernas förbannelse [The Curse of Minerals] has, for instance, been shown as part of the museum exhibition ‘Inland’10 at the Västerbotten Museum in 2015.

The video Our land, our water, our future is a 1:54-long English-language clip introduced with the words: ‘This video was shown in Stockholm 17/11 at [2012] at the manifestation “Our land, Our water, Our Future” (© Tor Lundberg)’.

Our land, our water, our future is composed of stills and moving pictures. The images depict water, a child drinking out of a guksi (Sámi drinking vessel of birch wood), a person swimming in a lake, a reindeer herd in a snow landscape, a child making a snow angel, animals in the forests. A female voice accompanies the video declaims: ‘Clean water, fresh air, white snow, deep forests. This is where we come from. This is what we live off’. As the voice continues speaking, the film shows people picking berries and herbs, hunting, fishing, boiling water over an open fire, cooking and eating outdoors, all activities that are in harmony with nature, that use natural resources, and that involve children.

Fig. 3.3 Screenshot from Our Land (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5p6BygBUmGA)

A shift occurs in the story, however, when the voice says:

Now, [the] mining industry threatens to destroy our lands. Companies from all over the world want to convert the natural wealth into money. They leave only devastated mountains, forests and rivers behind: an impoverished future for our children.

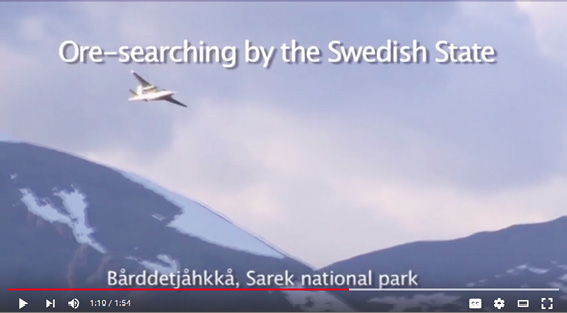

At 0:57 in the film, a picture of Ruovddevárre, located in the Laponia World Heritage Area, appears along with the text ‘Owned by English Beowulf Mining’ — that is, the British company prospecting in Gállok. While the view zooms in on the mountain, we hear the sound of an explosion. The mountain and trees tremble. Next, we see a photo of Sarek National Park, the world heritage area of Laponia, while hearing the sound of an airplane in the background. A text reads: ‘Ore-searching by the Swedish State. Bårddetjåhkkå, Sarek national park’.

Fig. 3.4 Screenshot from Our Land (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5p6BygBUmGA)

Following that is a picture with the text ‘Gállok (Kallak) owned by English Beowulf mining’. Here again, we hear the sound of ongoing blasting. A hole emerges in the middle of the picture that expands to another photo: one of a mine (an open pit). The forests and mountains are erased by the mine, illustrating what Gállok would look like if a mine were to be built there.

Fig. 3.5 Screenshot from Our Land (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5p6BygBUmGA)

The loud noise of machines takes over and the frame suddenly becomes a dark screen. The voice comes back, asking ‘Is this what we need? Is this what we want?’. The video concludes with brief information about the producer.

This video is built as a story that begins with humans in harmony with nature. The natural resources are berries, game, fish, etc. A complication in the narrative occurs when the mining industry comes into the picture. In the second part of the story, the harmony is disrupted. This disruption is visualised through the blurring of images, trembling, and noises. The end of the story is uncertain. The narrative voice turns back to the audience, sharing the concern depicted in the film, as well as a sense of responsibility.

Contesting Narratives

The two short films presented above produce two parallel discourses about the environment. These discourses stand out by virtue of their contrast, which establishes them as mutually exclusive. One discourse focuses on sustainability, harmony between humans and nature, and a long-term perspective. The other focuses on exploitation (mining) and how it affects the landscape. The portrayal of an exploitative attitude’s effects on the environment amounts to a portrayal of devastation which reinforces the idea of preservation suggested in the first discourse.

Although these ways to represent the environment stand in contrast to each other, they are presented from the same perspective. Traditional use of the environment and traditional interaction with the land and the landscape are core values. Other uses and interactions, an open pit for instance, are associated with devastation.

The articulation of the two conflicting discourses on the environment does not suggest a dialogue between the two different representations. When it comes to communication, these films are concerned with communicating one perception of the environment, that of the protest movement opposed to the mining industry; they do not communicate the discourses of the pro-mining movement.11

Bringing into question the existence of local people, exemplified by the statement of Clive Sinclair-Poulton, transforms Gállok into a ‘terra nullius’ (Fitzmaurice 2007), an unoccupied area belonging to no one. This discourse legitimises exploitation of the area. It also justifies the area’s use as a potential solution to the shortage of jobs and an increasing need for minerals (cf. Frost 1981).

The question ‘what local people?’ is therefore a strong rhetorical position. It does more than question the presence of a local population and local rights to land and water. Those who feel a strong connection to that particular place find their identity and existence questioned. The short films described in this chapter can be interpreted as a response, an effort to increase the visibility of people in the Sápmi region. The films and stills show locals (presumably) in interaction with nature — not a terra nullius. Human presence in the landscape is almost exclusively represented by local people. The ‘others’ are machines, represented here by an airplane, digging machines, and other heavy equipment. Politicians and leaders from the mining industry are not present on site; they appear in excerpts from the media’s coverage. The human presence involved in the area’s exploitation is, accordingly, toned down and hidden behind machines. This creates a dehumanisation of the mining industry that in itself produces a contrast with the anthropomorphism of nature illustrated in the first part of each video.

Both videos make use of rhetorical techniques to include the audience. The online visitor is not addressed as a passive viewer: at the end of each video, the audience is asked ‘Is this what we need? Is this what we want?’, and is reminded that ‘You can choose — your children and grandchildren cannot’. The use of ‘we’ and ‘you’ explicitly addresses the person watching the video. Thus, the audience is asked to take a side when faced with the two contrasting views of nature and the environment. The use of pronouns such as ‘we’ and ‘our’, however, does not only serve to include the audience. They also express a sense of possessiveness. Still more directly, the question of responsibility is addressed — that is, the mining industry’s and politicians’ irresponsibility. At the end of each of the short films, the question is turned back to the viewer: what is YOUR choice? Take a stand! — that is to say, assume responsibility.

The videos give an illusion of interaction: ‘you’ can choose how the narrative will continue, how it will end. The course of the film is determined, but what will happen next is indeterminate. In Vägvalet, we are invited to contribute to developing the narrative towards a harmonic interplay between humans and nature, by agreeing to ‘join the movement’.

Media Logic

‘Activist media’ (Lievrouw 2011) set themselves apart from traditional communication by being different channels rather than different forms of communication. As has been emphasised in other studies (Altheide 2013), the conceptual logic remains unchanged across media. This media logic is ‘a form of communication and the process through which media transmit and communicate information’ (Altheide 2013, 225). The video clips are examples of tools for communicating points of view and perceptions of nature. They are not isolated; their context, i.e., their origin in activist movements and reactions to prospections in Gállok and in Sápmi, is formed not only by the contemporary debate about the environment and indigenous rights, but also by the media landscape from which they emerge, as well as by a social logic composed by power structures and authorities.

The debate links together different networks of alternative and marginalised voices, authorities and elites. In the videos, one can discern the following networks: Sámi reindeer herders, other locals, environmental activists — through reference to the demonstration in Stockholm — politicians, and the mining industry. Authority and power relations are expressed in the positions given to the actors. Politicians are viewed in settings that denote authority, such as political meetings and conferences. Locals, on the other hand, are portrayed as isolated from larger social contexts, but in their home environment, illustrating traditional knowledge and emic understanding — which also lends authority.

The offline context in which the YouTube clips emerged is yet another aspect to be taken into account. The film by Tor Lundberg Tuorda, for instance, was shown at a demonstration. Tuorda and whatlocalpeople (as a YouTube account and a catch phrase) are closely associated with the coverage of the events of Gállok in the summer of 2013. At that time, neither local nor national media were covering the conflict. The first police actions at the site would have taken place unnoticed had it not been for the cameras and smartphones of activists and locals. Amateur films were posted on YouTube and photos were shared on social media forums, eventually attracting the attention of international and, subsequently, Swedish media.

The issue of exploitation and land rights has, since then, attracted the attention of the mass media and been the topic of several articles in international, national, and local newspapers. It has been the subject of books (Müller 2013; Müller 2015; Tidholm 2012) and national and international television documentaries. Before such attention, the topic was rarely discussed in media or touched upon in public discourse. Emic perspectives were marginalised. Today, even though locals and environmentalists have succeeded in making their voices heard in the mass media, neither these media nor public discourse sufficiently reflect the variety of perspectives on the issue.

The video clips discussed in this chapter operate within the context of a debate about exploitation in Sápmi. They borrow elements from media and political discourses, from demonstrations, and from activism. This entwinement and interplay between the videos and the social logic of the debate illustrate the ‘new social condition’ defined as mediatization, where ‘the media may no longer be conceived as being separate from social and cultural institutions’ (Hjarvard 2013).

The clips make use of principles of form, language, and aesthetics borrowed from other media. Depictions of nature as harmonious, quiet, and rich have connotations similar to those found in advertisements promoting biological products or tourist brochures, for instance. But the videos also copy other media, such as traditional media news channels: the banner at the bottom of the screen, with its informative text, and the chaotic pictures (movement, sound) bring to mind reports from conflict areas. The voice that interrupts Louis Armstrong in Vägvalet suggests a reporter trying to make us pay attention to a live report from the field, thus creating an impression of immediacy.

In terms of affordance and usability (Norman 1999), YouTube facilitates the diffusion of the videos, which can be posted or linked to on other social media platforms — common sharing practices that can result in a quick, free, and large-scale dissemination of information. The short format of the videos and the fact that information about the legislation (the Environmental Code) is given in an accessible way — devoid of legal jargon — also increases the videos’ usability.

Mediatization and media logic imply that short films, such as those studied here, create and are forced into a mode of communication that is familiar, appealing, and recognisable in terms of language and framing. The format of the films makes it apparent that they were produced with limited resources. Thus, even an uninformed viewer would rapidly recognise these videos as the products of activists rather than as the products of the mining industry or a lobby organisation. In a polarised debate such as this one, the ‘home-made’, DIY aspect lends credibility and authenticity to the message that the video clips convey.

The choice of aesthetics, language, and principles of form indicates that the producers prefer to communicate according to the logic and mechanism typical of activist movements, rather than adopt the system mechanisms used by professionals. The media logic of activist media prevails here. This implies that the videos address an audience that recognises and is receptive to this particular logic. Interestingly, although the DIY aspect of these activist initiatives is manifest in the format, some aspects are, on the other hand, ‘borrowed’ from traditional media (the banner, the speaker voice) — as discussed above.

The music in the short videos is another vehicle for perspectives, ideologies, and identities. ‘What a Wonderful World’ and the soundtrack of Our land reinforce the sense of harmony expressed in the photos and moving pictures. The song Staten och kapitalet in the second part of Vägvalet, an anti-capitalist critique of the relation of the state to capitalist corporations, is a Swedish classic. It was created by the Progg-band12 Blå tåget [Blue Train] in 1972. The version used in the video is a cover from 1980s by the Swedish punk band Ebba Grön. The choice of the song in itself conveys an ideology and a message (Arvidsson 2008). Re-emerging in a new context, the song carries power and resonance from the original context (Frandy 2013), creating continuity between anti-capitalist movements of the 1970s and environmental activism in 2013.

The familiar narrative structure of the videos contributes to their affordance. The narratives of the two clips are similar and follow a structure recognisable from oral genres. Borrowing terminology from narrative research (Labov and Waletzky 1967), we can describe this structure as consisting of various phases, including an abstract (an introduction to what the story is about, that is, the traditional use of the land), an orientation (the main actors are local people, the story takes place in Sápmi, in our time), and a complicating action (exploitation). The next phase, the evaluation, tells us about the threats and dangers that arise. The concluding phases (result and coda) are not provided; the story remains incomplete and the viewer is addressed directly, encouraged to influence the final outcome. The course of action is simplified and the actors are depicted, crudely, as good and peaceful or bad and aggressive. Nature is anthropomorphised, while the workers of the mining companies are left out, with the focus being on technique and infrastructure.

Due to the format and the context of the production of short films, it is a challenge to present the complexity of the situation. To some extent, the narratives illustrated in Vägvalet and Our land fail in representing the many actors, the variety of perspectives, the various conditions, and the geographical specificity of different mining projects at play in the debate over exploitation in Sápmi. On the other hand, communicating a message concerning the environment in the format of a short video in participatory media inherently implies and requires a degree of simplification. This is the case in the videos meant to reach out and illustrate the impact of mining in Sápmi.

The anonymous producer(s) of the whatlocalpeople homepage and user of the YouTube account of that same name both stress the utility of participatory media as a benefit. ‘It is a good way to convey a message, by linking […] One can quickly get a knock-on effect’.13 The producer also mentioned the opportunity to be thought-provoking without forcing an interpretation on people. ‘One must make people think, not make things too easy for them — let them put two and two together’.

To achieve this, the producer uses pictures and films, ‘as a complement to text. It can be tiresome to read a compendium. But with pictures, one can create interest in reading that compendium. Like the pictures in opinion pieces in DN [Dagens Nyheter, the national newspaper]’.

When it comes to the participatory aspects of these YouTube videos, it is difficult to determine their impact. Vägvalet had (as of 18 February 2015) no visible comments on YouTube; it had 944 viewings. Our land had 493 viewings and 2 comments to the producer (by 18 February 2015). The videos have been spread on Facebook, a platform more welcoming to comments and responses than YouTube. Interaction through comments, in other words, takes place to a greater extent outside the frame of YouTube. Sharing videos on other platforms, such as Facebook, is indeed in itself a mode of interaction. Although it would be relevant to examine the reception of the videos in relation to the producer’s intention and ambition to reach an audience, this falls outside of the scope of this chapter.

Polarisation or Zone of Contact

One important question in studies of activism and social media is whether social media can create a zone of contact for increased dialogue between the parties in a conflict, or if, on the contrary, social media contribute to a polarisation of the debate by creating spaces primarily for those who are already in agreement with each other.

In the case of this particular study, there is one aspect that one must keep in mind. The general Swedish population has little knowledge of Sámi culture, history, and living conditions. Lack of knowledge is one factor that might complicate the creation of mutual understanding, leading to a polarisation of the debate. From this perspective, any effort aimed at spreading knowledge and information about Sápmi as a cultural landscape, and about its population, would improve people’s understanding of the Sámi perspective on the conflict.

The controversy over mining and exploitation is, however, not only a Sámi issue. It is also an environmental concern, a question of human and indigenous rights. Debates over the opening of new mines are related to specific geographical places. The environment and specific places become common denominators for various groups concerned with the issue — environmentalists, reindeer herders, indigenous rights activists, and locals. The importance of local attachment in framing social movements is articulated in social media. These media play a role in bringing together different groups and interests in activist movements, as happened in the case of the movement against the mining industry. Participatory media are a meeting point where one talks, organises, fetches and spreads information; they facilitate the emergence of networks. From this perspective, social media constitute a zone of contact (cf. Pettersen 2011) for different groups concerned with the same issue.

The question remains, however, whether social media can be a zone of dialogue and exchange for those on opposite sides of a debate.14 The videos, through their aesthetics and principles of form and language, address an audience receptive to arguments about sustainability, environmental preservation, traditional use of natural resources (fishing, berry picking, etc.), and respect for the natural and cultural landscape. The opposite standpoint is depicted in negative terms, with focus on devastation, destruction, disturbance, and greed. As seen from this perspective, the videos do not invite dialogue. Rather, these examples illustrate how participatory media are used for creating a space for marginalised voices and counter discourses, and for diffusion of information.

The videos also address people who are interested in debating the advantages and disadvantages of the mining project as it relates to the wider issue concerning the exploitation of natural resources. At the very least, the videos might ‘make people think’, to quote the producer of whatlocalpeople. The videos invite people to take sides. They give information; they communicate a perspective in an effort to convince. To address such a heterogeneous audience is naturally challenging. The videos elaborate a perception of the environment and of the relationship between landscape and people based on a direct, unmediated experience of nature. Part of the audience might very probably be composed of people who have experienced nature in Sápmi only from a distance. Discourses about, and representations of, a landscape from which the actor is distanced tend to reproduce a ‘coloniser gaze’ (see for instance Jørgensen 2014) as opposed to a local gaze. There is a risk that communicating nature through Internet videos to a broad audience might, thus, create distance to the landscape. The clips are produced from an emic, local perspective, and their context of production (including producers, social context, media logic, and conduits) must necessarily be taken into account if one is to fully understand the relationship between the landscape and people that these clips illustrate and shape.

Conclusions

The short videos do more than provide a narrative about the environment. They can also include, reflect, and shape the debate about mining in Sápmi. They illustrate how, for voices in the margin, participatory media open up alternative modes of outreach communication. These can be means for self-representation, in this case they allow the locals to stress their presence in the landscape and their view about what nature is. The circulation of information which YouTube made possible is primarily a diffusion of information in an effort to raise awareness.

The perception of nature and the environment shaped and narrated in the films focuses on harmony and the interaction between people and landscape that results from traditional land use. The way in which nature is depicted is framed by the need to protect the environment and assume responsibility, particularly now when exploitation threatens its existence.

The videos present polarised narratives. Although these narratives represent two differing views on natural resources, they do so from a single perspective. They represent the point of view of people who have a specific agenda, one of many viewpoints expressed during the debate. Other actors, such as local pro-mining movements, are not represented. This simplification of the debate can be understood as partially rhetorical, a consequence of a media logic and mode, influenced by the choice of media. This chapter’s analysis of the films indicates that their main target audience are those concerned about issues such as environmental preservation.

It would therefore be hazardous to draw conclusions about the potential of participatory media for opening a dialogue or for preventing conflict. But, less than two years after the publication of the first YouTube videos of the kind discussed here, the topic of the mining boom on indigenous land has moved from the periphery to the centre of public debate. Undeniably, extensive use of YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and blogs during and after the conflict in Gállok has, at the very least, helped trigger this shift.

References

Altheide, David L., ‘Media Logic, Social Control, and Fear’, Communication Theory, 23(3) (2013), 223–238, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/comt.12017

Arvidsson, Alf, Musik Och Politik Hör Ihop: Diskussioner, Ställningstaganden Och Musicerande 1965–1980 (Möklinta: Gidlund, 2008).

Bruns, Axel, Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and Beyond: From Production to Produsage (New York: Peter Lang, 2008).

Cocq, Coppélie, ‘Kampen Om Gállok. Platsskapande Och Synliggörande’, Kulturella Perspektiv. Svensk Etnologisk Tidskrift, 23(1) (2014a), 5–12.

―, ‘Att Berätta Och återberätta: Intervjuer, Interaktiva Narrativer Och Berättigande’, Kulturella Perspektiv. Svensk Etnologisk Tidskrift, 23(4) (2014b), 22–29.

Dahlberg, L., ‘Rethinking the Fragmentation of the Cyberpublic: From Consensus to Contestation’, New Media & Society, 9(5) (2007), 827–847, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1461444807081228

Dean, Jodi, ‘Why the Net Is Not a Public Sphere’, Constellations, 10(1) (2003), 95–112, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.00315

Evernden, Lorne Leslie Neil, The Social Creation of Nature (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992).

Fitzmaurice, Andrew, ‘The Genealogy of terra nullius’, Australian Historical Studies, 38(129) (2007), 1–15, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10314610708601228

Frandy, Tim, ‘Revitalization, Radicalization, and Reconstructed Meanings: The Folklore of Resistance During the Wisconsin Uprising’, Western Folklore, 72(3–4) (2013), 368–391.

Frost, Alan, ‘New South Wales as terra nullius: The British Denial of Aboriginal Land Rights, Historical Studies, 19(77) (1981), 513–523, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10314618108595656

Fuchs, C., ‘Alternative Media as Critical Media’, European Journal of Social Theory, 13(2) (2010), 173–192, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1368431010362294

Hjarvard, Stig, The Mediatization of Culture and Society (New York: Routledge, 2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203155363

Jørgensen, Finn Arne, ‘The Armchair Traveler’s Guide to Digital Environmental Humanities’, Environmental Humanities, 4(1) (2014), 95–112, http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3614944

Labov, William, and Waletzky, Joshua, ‘Narrative Analysis’, in Essays on the Verbal and Visual Arts, ed. by J. Helm (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1967), pp. 12–44, http://www.ling.upenn.edu/~rnoyer/courses/103/narrative.pdf

Lievrouw, Leah, Alternative and Activist New Media (Cambridge: Polity, 2011).

Müller, Arne, Smutsiga Miljarder. Den Svenska Gruvboomens Baksida (Skellefteå: Ord & Visor, 2013).

―, Norrlandsparadoxen — En Utvecklingsdröm Med Problem (Skellefteå: Ord & Visor, 2015).

Norman, Donald, ‘Affordance, Conventions and Design’, Interactions, 6(3) (1999), 38–43, http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/301153.301168

Nye, David E., Rugg, Linda, Fleming, James and Emmet, Robert, ‘The Emergence of the Environmental Humanities’ (2013), http://www.mistra.org/download/18.7331038f13e40191ba5a23/Mistra_Environmental_Humanities_May2013.pdf

O’Neil, Mathieu, ‘Hacking Weber: Legitimacy, Critique, and Trust in Peer Production’, Information, Communication & Society, 17(7) (2014), 872–888, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2013.850525

Olin-Scheller, Christina, and Wikström, Patrik, ‘Literary Prosumers: Young People’s Reading and Writing in a New Media Landscape’, Education Inquiry, 11 (2010), 41–56, http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/edui.v1i1.21931

Pettersen, Bjørg, ‘Mind the Digital Gap: Questions and Possible Solutions for Design of Databases and Information Systems for Sámi Traditional Knowledge’, Dieđut 1 (2011), 163–192.

Plumwood, Val, Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason (London: Routledge, 2002).

Rydberg, Tomas, Landskap, territorium och identitet — exemplet Handölsdalens sameby (Landscape, territory and identity — examples Handöldalens Sami village). Kulturgeografiska institutionen. Forskarskolan I Geografi (Uppsala: Uppsala universitet, 2011), http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:413828/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Sassen, Saskia, ‘Local Actors in Global Politics’, Current Sociology, 52(4) (2004), 649–670, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0011392104043495

Swedish Environmental Code, SFS 1998:808 (Stockholm: Ministry of the Environment and Energy, 1998), http://www.government.se/contentassets/be5e4d4ebdb4499f8d6365720ae68724/the-swedish-environmental-code-ds-200061

Tam, Kim-Pong, Lee, Sau-Lai and Chao, Melody Manchi, ‘Saving Mr. Nature: Anthropomorphism Enhances Connectedness to and Protectiveness toward Nature’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49 (2013), 514–521, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2013.02.001

Tidholm, Po, Norrland: Essäer Och Reportage (Luleå: Teg Publishing, 2012).

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005).

Internet resources

Videos by Tor Lundberg Tuorda:

Our Land, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5p6BygBUmGA

The Parasite, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IYM3grMxYJs

Videos by Whatlocalpeople:

The Answer https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-FPeOPTDhio

Poem, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JiFcEvjIG8w

Vägvalet, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=adJDdTw5AsQ

Gruvmotståndet trappas upp i Gállok, dag 1, https://www.youtube.com/watch

?v=5Ry06RncwYI

Polisingripande i Kallak, del 3, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YhhFdLvPinU

Other resources

Exhibition

Inland, Västerbottens Museum, http://www.inland.nu

Interviews

Tor Lundberg Tuorda (30 May 2013), personal interview.

Producer of Whatlocalpeople (31 May 2013), personal interview.

1 The research for this paper was financially supported by the Swedish Foundation for Humanities and Social Sciences, Riksbankens Jubileumsfond.

2 Andersson and Cocq, ‘Nature Narrated. A Study of Oral Narratives about Environmental and Natural Disasters from a Folkloristic and Linguistic Ethnographic Perspective’, 2012–2014.

3 http://www.whatlocalpeople.se/vi-finns [my translation].

6 For instance: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Ry06RncwYI; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YhhFdLvPinU

8 Personal interview, 30 May 2013.

9 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IYM3grMxYJs, published on 23 January 2015.

11 A study of how nature is communicated by the pro-mining advocates is not included in this chapter.

12 Progg was a left-wing, anti-commercial musical movement in Sweden in the late 1960s and 1970s.

13 Personal interview, 31 May 2013.

14 Without data about the consumption and reception of the YouTube videos, any discussion of their impact on pro-mining advocates would be hazardous.