3.3: How We Got Here- Lifting “The Veil”

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 143290

- Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick & Teresa Hodges

The Veil and Double-Consciousness

In Sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois’ (1903) seminal work outlining double consciousness theory, he argued that “the problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line” (p. 281). Despite reductions in de jure racial discrimination, which is legally codified explicit racism, improved racial attitudes among the general public, and the election of the United State's first biracial Black president, the trouble of the color line persists in reproducing racial disparities in the United States and around the globe (Alexander, 2010; Bobo, 2017; Bonilla-Silva, 2013; Williams and Collins, 2001). As exemplified by the 2016 election of a Presidential candidate who campaigned on an explicitly racist, anti-immigrant, and nationalist platform (Bobo, 2017), national discourse and political rhetoric have become more divisive while hate crimes and brutality towards people of color and immigrants have risen (Eligon, 2018).

In this context, the Du Boisian theory of double consciousness is relevant for understanding the racial politics of the 21st century. For Du Bois, double consciousness symbolized the psychological impact of living in a racist society for African Americans in the years following the end of slavery. Societal treatment of African Americans as a “problem” contributed to the development of the Veil, a lens through which [African Americans] viewed themselves from the perspective of White Americans. Despite being citizens, African Americans were not fully regarded as such, a plight that contemporary Black Americans and other Americans of color still experience.

The content in the preceding two paragraphs was initially published in the article "Double Consciousness in the 21st Century: Du Boisian Theory and the Problem of Racialized Legal Status" by Tiffany Joseph and Tanya Golash-Boza (2021, p. 345) in Social Sciences, which is licensed CC BY 4.0.

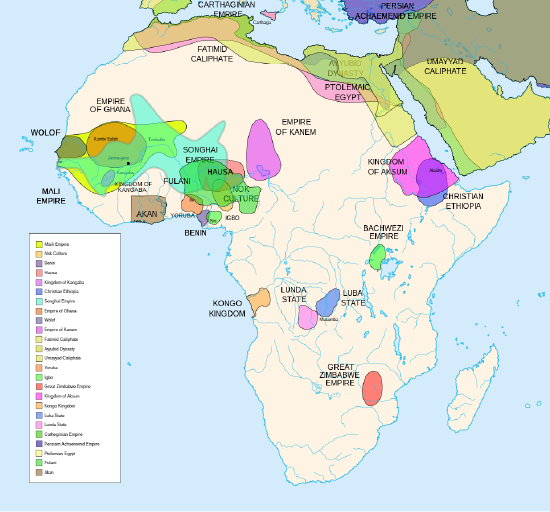

Pre-colonial Africa

The African continent has been home to complex human societies for over 10,000 years. Families formed tribal groups and created some of the first known markers of culture and social organization, including tools, sharing resources, and agriculture. Many groups co-existed peacefully, while others fought over territory and other disputes. Before any contact with colonial outsiders, multiple large empires and kingdoms were created with systems of trade, taxation, and political representation. In Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), there is a map that has the territorial borders of kingdoms and empires located throughout the continent, with some groups overlapping land claims with one or more other groups. This includes Mali Empire, Nok Culture, Fulani Empire, Akan States, Benin, Hausa, Kingdon of Kangaba, Christian Ethiopia, Songhai Empire, Empire of Ghana, Wolof, Empire of Kanem, Fatimid Caliphate, Ayyubid Dynasty, Umayyad Caliphate, Yoruba Yorubaland, Igbo, Great Zimbabwe, Kingdom of Aksum, Kongo Kingdom, Luba State, Lunda State, Carthaginian Empire, Persian Achaemenid Empire, and The Ptolemies.

For many centuries, the tribal groups and empires of Africa operated with relative autonomy. There was no sense of African or Black identity, but people identified instead with their local context, such as the Kingdom of Kush, which bordered Egypt to the south around 1070 BCE. One of the largest and most powerful empires was the Kingdom of Aksum, which operated for nearly a thousand years in the areas now claimed by Eritrea and Ethiopia. The kingdom of Ghana was the first state with a system of political representation starting in 350 CE. Outsiders to the continent first spread influence in the 600s, with the proliferation of Islam across northern Africa. Then, in the 15th century, Europeans, beginning with the Portuguese, began to arrive in large boats and enslave large numbers of West Africans from various groups and empires (Finlayson, 2020).

Chattel Slavery

By 1700, 50,000 people were being enslaved each year, and scholars estimate that, in total, 12 million African people were captured and trafficked to the western hemisphere (Finlayson, 2020). This historical era was defined by what scholars call the Transatlantic Triangular Trade, which exploited the people and natural resources of West Africa and the eastern segments of North, Central, and South America for the financial benefit and production of industrialization in Europe and European colonies. In Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), a map displays visual icons representing the flow of people and products between the three regions. Arrows depict the flow of people and goods from each region. From Europe to West Africa: textiles, weapons, iron, and alcohol; From West Africa to Europe: gold, spices, and wood; From West Africa to South America: slaves; From West Africa to the Caribbean: gold, slaves, and spices; From the Caribbean to West Africa: textiles, spices, alcohol, and tools; From the Caribbean to the southeastern colonies: slaves, spices; From southeastern colonies to the Caribbean: wood, flour, fish, and meat; From the colonies to Europe: tobacco, wood, and fur; From Europe to the colonies: textiles and luxury items.

In response to the widespread abduction and enslavement of African people, communities resisted this form of colonization and exploitation. Rebellions broke out on the ships that carried Africans to the western hemisphere, while others took their own life by jumping into the sea to avoid being enslaved and forced into hard labor. African people and their descendants have continued this legacy of resistance through a shared commitment to survival, political protest, armed rebellion, solidarity with Native Americans and Indigenous peoples, forging family connections, and building community with biological and chosen kin. At least 250 organized rebellions were conducted that included a group of 10 or more enslaved people, and countless more small-scale and individual rebellions were carried out (Zinn, 2015). In the United States, the colonial economy was built on the labor of slaves, including the large-scale cotton plantations in the South, as well as the infrastructure, construction, and service labor industries. In Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), a painting of two Black women cotton pickers shows the central work done by enslaved women of African descent in the United States amidst the vast and prosperous fields that resulted.

The system of chattel slavery meant that not only were individuals enslaved, but their descendants inherited the quality of being enslaved as well. To maintain this on a large scale, a racialized ideology of dehumanization and exploitation was created, which has grown and evolved over time to reproduce inequity and injustice in different forms. This can be understood through the many laws that legally defined Black people as property. Following the American Revolution, in which settlers of European descent overtook the system of colonial rule, the U.S. Constitution was built around this system. The three-fifths compromise was a decision in the 1787 U.S. Constitutional Convention that determined that while enslaved people were not eligible to vote, they would be counted toward the population when determining the number of representatives from each state, but only at 3/5th the rate of the free, white population. This meant that slave-owning states would have increased representation based on the number of enslaved people in their state despite those people not being represented in elections. This was the law of the land, which was supported by Court decisions like Dred Scott v. Sandford. In 1856, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Black people were never meant to be included within the terms of citizenship defined by the U.S. Constitution. The government would continue to support the maintenance and growth of slavery.

Sidebar: Voting Rights and Representation

Although the three-fifths compromise is no longer officially used in counting the population for elections, it still lives on in the current-day prison system. In 48 states, individuals who are convicted of a crime lose their right to vote while serving their sentence, and in 11 states, individuals must file a special petition to restore their voting rights, even after completing all terms of punishment, probation, and parole. However, those individuals are still counted toward the population when creating district maps and determining levels of representation. Individuals are counted in the communities where they are incarcerated, and this creates a pattern where white, middle-class communities gain political standing through the increased population, despite the prison population being disproportionately low-income and people of color. For up-to-date information on this topic and details about the policy in your state, you can view the interactive map of voting rights on the Movement Advancement Project website.

Abolition Movement

Resistance to slavery is as old as the institution itself. As noted above, people who were captured for the purpose of being enslaved often fled, fought back, or willfully ended their lives to avoid themselves and their families being forced into labor. In addition, religious and political elites critiqued the institution of slavery and the economies that built their prosperity on the backs of slave labor. Prominent among these voices for freedom were free Black people who fought against racist laws to receive an education and speak for human rights. This included prominent figures like Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglas, and Harriet Tubman. Harriet Tubman, shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\), was also famous for her daring leadership in helping to free enslaved people and bring them to safety through a network of activists called the Underground Railroad. The Underground Railroad operated to provide safe hiding spaces and routes of travel for self-emancipated people who were fleeing to places where slavery was not legal and they could begin life anew. This included Canada, Mexico, and for a period of time, the Spanish-controlled colony of Florida.

Abolitionist activists also created pressure to outlaw slavery and prevent its growth into new territories. Ongoing tensions between abolitionism and the proponents of slavery eventually resulted in the U.S. Civil War, a five-year struggle from 1861-1865 in which southern slave-owning states seceded from the United States in order to continue the institution of slavery. During the war, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which gave the U.S. army the legal right to free enslaved people in the confederate states. The union army eventually won the war, in part due to the bravery and hard work of Black people from the north and south who often fought in the most dangerous and perilous parts of the war. In June of 1865, union general Major General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, and proclaimed freedom for the people still held in bondage and slavery in Texas.

This became the basis of Juneteenth celebrations, which are observed in Mexico and the United States and commemorate the end of slavery and the hard work that led to that victory. At the end of that year, the U.S. Congress passed the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which formally abolished chattel slavery throughout the country. It states:

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Importantly, the amendment allows for slavery in cases where the individual is convicted of a crime. This amendment is used by federal and state governments to employ incarcerated individuals for paltry wages, at hourly rates of less than $1/hour, a system which constitutes a continued version of legal slavery (Alexander 2010). You can learn more about the prison industrial complex in the context of current systems of control and exploitation in Chapter 10.

Sidebar: Attacks on Historical Truth, Black Studies, and the 1619 Project

The institution of racialized slavery came to American shores in 1619. On the 400th Anniversary of this event, historian Nikole Hannah-Jones launched The 1619 Project with the New York Times magazine to highlight this history and its legacy on Black communities and racial politics today. While this project is rooted in decades of peer-reviewed historical research, it has come under attack in conservative attempts to censor “Critical Race Theory,” among other aspects of discussing race, racism, and identity in schools. Critical Race Theory is an advanced legal framework that examines the relationship between U.S. laws and systemic racism. However, there are seventeen states that have created a ban on Critical Race Theory in K-12 schools through state-level executive action or legislation, along with four states currently considering such measures, as of September 2022. For up-to-date information on this censorship, you can visit the Edweek article on the topic, which details current information about legislative efforts targeting Critical Race Theory. Similarly, state-approved textbooks in places like Texas often exclude mention of slavery or use misleading language to describe enslaved peoples as immigrant workers without mention of the historical realities that were enacted on slaves (Isensee 2015).

Reconstruction

The end of the Civil War in 1865 led to a wide-scale economic, cultural, political, and social shift in the United States. While the end of slavery was a huge achievement, the promise of equal opportunity and citizenship still faced significant resistance in the laws, traditions, and beliefs of the nation. Formerly enslaved Black communities had their basic freedom restored, but this did not undo the legacy of hundreds of years of forced labor, institutionalized sex slavery, being barred from education, intentional separation of families, and the destruction of traditional religious and cultural practices rooted in West African traditions.

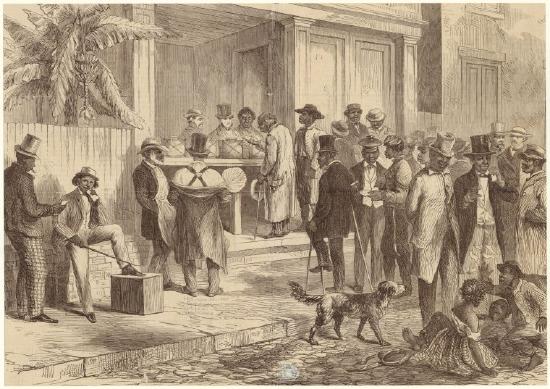

The government sought to provide aid through the creation of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and religious organizations provided basic services like food and education for children. During this time, Black people sought to exercise their right to vote and nurtured autonomous institutions of education, religion, and trade. In Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\), an artistic rendition is shown of free Black men in 1867 voting in New Orleans. Although there were no reparations from the government or from employers for years of unpaid wages, Black communities used their knowledge of the land and community ties with one another to begin healing from the history of slavery and working for justice.

The Era of Jim Crow

The Reconstruction years saw many gains for the newly freed Black populations living in the United States at that time. However, while federal protections created a favorable political context in general, local realities were heavily influenced by regional and state laws and practices that maintained discrimination. These new laws, called Black Codes, were laws that created restrictions on Black people’s abilities to own property, conduct business, lease land, and move freely through public spaces. These regulations worked to keep separate the established white society from the lives of Black people.

It is unsurprising that in 1877 when federal troops were removed from the U.S. South, policies rapidly shifted to what is now called the Jim Crow era. This was a time when public institutions actively established racial segregation. Despite the promises of the 14th and 15th Amendments that Black people would enjoy the rights and responsibilities of full citizenship, segregation created an explicitly tiered version of citizenship. The Courts upheld this doctrine through the notion of “separate but equal,” which was codified in the 1896 decision in the Plessy v. Ferguson case. While separate but equal was eventually struck down in the 1950s it took nearly a century of activism to achieve this fundamental civil rights perspective.

When racial identity became a legal category of inclusion and exclusion, that also meant that race had to be clearly defined. In practice, the “one drop” rule was applied to mixed-race people, meaning that if you had even one drop of Black blood, that made you legally and socially considered to be Black. While identity is much more complicated than one’s heritage or genetic material, this idea has enduring effects on the treatment of people of color in the United States.

Sidebar: Black Wall Street and the Tulsa Race Massacre

In the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, Black business owners and professionals had organized a prosperous and autonomous area, which included Black-owned grocery stores, newspapers, movie theaters, churches, and healthcare providers. The city was a testament to Black communities’ capacity and a centralized hub of intellectual and financial capital. It became known as Black Wall Street due to its economic, political, and social significance. However, in 1921, the District was massacred by a white mob for two days in one of the largest acts of racialized terrorist violence in U.S. history. Hundreds of people died or went missing, and nearly a thousand were injured. This attack was devastating not just for the victims, but it also became an enduring symbol of the threat of white violence in the face of Black prosperity, fueling the flames of white supremacy.