Figure \(2.3.1\): Mojave group. Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository

There is some variation in cultural gender-role standards both within the United States and across cultures; however, within the United States, for example, standards vary depending on ethnicity, age, education, and occupation. These variables will be discussed more fully in coming chapters. But now that we’ve explored the definitions and constructions of sex and gender, let’s more closely examine some traditional gendered norms from cultures that don’t totally reflect Eurocentric, Westernized ways of doing gender.

Mojave Native Americans

First we’ll talk about the Mojave in North America. This culture taught and reinforced parallel institutional structures for males and females.15 For example, the Mojave husbands and wives worked together to farm their fields. Men planted and watered the crops, and women harvested them. Both sexes took part in storytelling, music and artwork, and traditional medicine.16

In Mohave society, pregnant women believed they had dreams predicting the anatomic sex of their children. These dreams also sometimes included hints of their child’s future gender variant status. A boy who “acted strangely” before he participated in the boy’s puberty ceremonies in the Mohave tribe would be considered for the transvestite ceremony. The ceremony itself was meant to surprise the boy. Other nearby settlements would receive word to come and watch. A circle of onlookers would sing special songs. If the boy danced like a woman, it confirmed his status as an alyha. He was then taken to a river to bathe, and was given a skirt to wear. The ceremony would permanently change his gender status within the tribe. He then took up a female name. The alyha would imitate many aspects of female life, including menstruation, puberty observations, pregnancy, and birth. The alyha were considered great healers, especially in curing sexually transmitted diseases like syphilis.

Oaxaca, Mexico

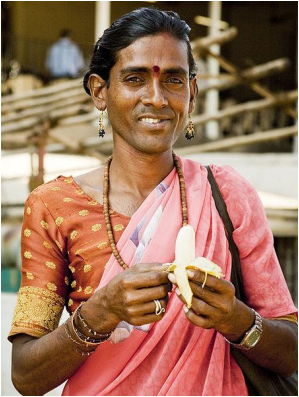

Figure \(2.3.2\) Muxe: Mexican men who take on the traditional dress and gender roles of Mexican women within their communities.

The Juchitán in Oaxaca, Mexico, practice gender norms that do not comply with traditional Western practices. For example, the women traditionally run businesses, wear colorfully bold traditional clothing, and hold their heads firmly high. The women are regarded as being empowered and the tolerance of homosexuality and transgender individuals has been part of their cultural tradition. men who take on the traditional roles of women, referred to as “Muxes,” are not only accepted, but cherished as symbols of good luck. This community exemplifies an alternative gender system unlike the binary gender categories that have been established throughout many parts of the world.

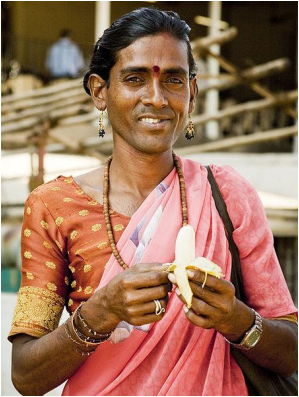

Indian Hijras

Figure \(2.3.4\) Hijra

In Indian Hindu culture, when compared to the native North Americans, the gender system is essentially binary, but the ideas themselves are quite different from Western thoughts. These ideas often come from religious contexts. Some Hindu origin myths feature androgynous or hermaphroditic ancestors. Ancient poets often showed this idea by presenting images with mixed physical attributes between the two sexes. These themes still exist in the culture, and are even still institutionalized. The most prominent group are the hijras.17 Hijras, today, are not seen either male or female, but rather are typically identified as “hijra.” “Being a hijra means making a commitment that gives social support and some economic security, as well as a cultural meaning, linking them to the larger world.”18

Brazil

As in Indian culture, Brazilian culture does follow a gender binary, just not the traditional western one. Rather than men and women, certain areas of Brazil have men and not-men. Men are masculine, and anyone who displays feminine qualities falls under the category of “not-man.” This concept is a result of sexual penetration as the deciding factor of gender. Any one who is penetrated is not-male. Everyone else, regardless of sexual preference, remains a male in Brazilian society.19

The most commonly discussed group of people when discussing gender in Brazil are the travestí, or transgender prostitutes. Unlike in native North America and India, the existence of the travestí is not from a religious context. It is an individual’s choice to become a travestí. Born as males, they go to extensive measures to try to appear female. The travestí recognize they are not female, and that they cannot ever become female. Instead, their culture is based on this man/not-man premise.20

Thailand

Figure \(2.3.5\) A Kathoey. Photo Source: https://maytermthailand.org/2015/04/27/the- third-gender-in-thailand-kathoey/

In Thailand the term kathoey is used by both males and females and allows and refers to cross-dressing and adopting masculine and feminine identities opposite their assigned birth gender. Up until the 1970s cross-dressing men and women could all come under the term kathoey, however the term has been dropped for the cross-dressing masculine females who are now referred to as tom.21 As a result of the shifts, kathoey today is most commonly understood as a male transgender category, and these people are now sometimes referred to as “lady-boys.” Kathoey is derived from the Buddhist myth that describes three original human sex/genders, male, female, and a biological hermaphrodite or kathoey.22 Kathoey is not defined as merely being a variant between male or female but as an independently existing third sex.

Nigeria

The Nigerian Yoruba social life and gender roles do not duplicate those found in the West. Instead of focusing on gender distinctions, this culture typically focuses on age distinctions. In addition, men who choose to wear women’s clothing, jewelry, and cosmetics will be labeled as “wife of the god,” as only women can be wives of mortal men.

Waria, Indonesia

Waria is a term used for the third gender in Indonesia outside of the masculine and feminine ideals in this Islamic nation. The waria are born male but live along a continuum of gender identity not constrained to the traditional Western interpretation of the masculinity. The term “waria” includes individuals who continue to identify as male but who imitate certain femi nine mannerisms, and can occasionally wear makeup, jewelry, and women’s clothing. Others identify so closely as female that they are able to pass as female in their daily interactions in society.

Sistergirls and Brotherboys, Australia

In Australia, indigenous transgendered people are known as "sistergirls" and "brotherboys". As in some other native cultures, there is evidence that transgender and intersex people were much more accepted in their society before colonization. Therefore, the Eurocentric tendencies that shaped Western gender ideals have also played a huge part in the contemporary view of the sistergirls and brotherboys in Australia today. For example, today there are more stigmas attached to these individuals. But through an increasing number of support groups specifically aimed at sistergirls and brotherboys, perhaps times will change again. If there’s anything we’ve learned from gender so far, it’s that it is constantly being constructed and re-constructed.

Mahu, Hawaii

In traditional Hawaiian culture, creative expression of gender and sexuality was celebrated as an authentic part of the human experience. Throughout Hawaiian history, “mahu” appear as individuals who identify their gender between male and female. A multiple gender tradition existed among the Kanaka Maoli indigenous people. The mahu could be biological males or females inhabiting a gender role somewhere between or encompassing both the masculine and feminine. Their social role is sacred as educators and conservators of ancient traditions and rituals. The arrival of Europeans and the colonization of Hawaii nearly eliminated the native culture, and today mahu face discrimination in a culture dominated by white Eurocentric ideology.

Suggested Articles for Further Reading:

Candace West; Don H. Zimmerman. (1987). Doing Gender. Gender and Society, Vol. 1, No. 2. (Jun., 1987), pp. 125-151.

Patricia A. Adler, Steven J. Kless and Peter Adler. (1992). Socialization to Gender Roles: Popularity among Elementary School Boys and Girls. Sociology of Education. Vol. 65, No. 3 (Jul., 1992), pp. 169-187.

Suggested Films:

Middle Sexes: Refining He and She (2005)

Examines the diversity of human sexual and gender variance around the globe, with commentary by scientific experts and first-handaccounts of people who do not conform to a simple male/female binary.

Two Spirits (2009)

Filmmaker Lydia Nibley explores the cultural context behind a tragic and senseless murder. Fred Martinez was a Navajo youth slain at the age of 16 by a man who bragged to his friends that he 'bug-smashed a fag'. But Fred was part of an honored Navajo tradition -the 'nadleeh', or 'two-spirit', who possesses a balance of masculine and feminine traits. Through telling Fred's story, Nibley reminds us of the values that America's indigenous peoples have long embraced. - Written by Outfest

Half the Sky (2012)

This documentary—filmed in 10 countries with narrations from celebrities such as Olivia Wilde, Eva Mendes and Meg Ryan—tellsuplifting stories of women around the world who are fighting back against systemic oppression. The film presents gender equality as the unfinished business of the our time and highlights women who are working to improve everything from healthcare to education.

15 Hill, W. W. (1935). The status of the hermaphrodite and transvestite in Navaho culture. American Anthropologist, 37,

273-279.

16 Nanda, Serena. Gender Diversity: Crosscultural Variations. Waveland Press, 1999. Print. Pages 21-23

17 Nanda, Serena. Gender Diversity: Crosscultural Variations. Waveland Press, 1999. Print.pg. 27,28

18 Ibid

19 Kulick, D. "The Gender of Brazilian Transgendered Prostitutes." American Anthropologist 99.3 (1997): 574-85. Page

578

20 Ibid

21 Nanda, Serena. Gender Diversity: Crosscultural Variations. Waveland Press, 1999. Print. Page 73

22 Ibid