11.2: Case studies

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 81941

The first approach to extracting metaphors from corpora starts from a source domain, searching for individual words or sets of words (synonym sets, semantic fields, discourse domains) and then identifying the metaphorical uses and the respective targets and underlying metaphors manually. This approach is extensively demonstrated, for example, in Deignan (1999a,b; 2005). The three case studies in Section 11.2.1 use this approach. The second approach starts from a target domain, searching for abstract words describing (parts of) the target domain and then identifying those that occur in a grammatical pattern together with items from a different semantic domain (which will normally be a source domain). This approach has been taken by Stefanowitsch (2004; 2006c) and others. The case studies in Section 11.2.2 use this approach. A third approach has been suggested by Wallington et al. (2003): they attempt to identify words that are not themselves part of a metaphorical transfer but that point to a metaphorical transfer in the immediate context (the expression figuratively speaking would be an obvious candidate). This approach has not been taken up widely, but it is very promising at least for the identification of certain types of metaphor, and of course the expressions in question are worthy of study in their own right, so one of the case studies in Section 11.2.3 takes a closer look at it.

11.2.1 Source domains

Among other things, the corpus-based study of (small set of) source domain words may provide insights into the systematicity of metaphor (cf. esp. Deignan 1999b). In cognitive linguistics, it is claimed that metaphor is fundamentally a mapping from one conceptual domain to another, and that metaphorical expressions are essentially a reflex of such mappings. This suggests a high degree of isomorphism between literal and metaphorical language: words should essentially display the same systemic and usage-based behavior when they are used as the source domain of a metaphor as when they are used in their literal sense unless there is a specific reason in the semantics of the target domain that precludes this (Lakoff 1993).

11.2.1.1 Case study: Lexical relations and metaphorical mapping

Deignan (1999b) tests the isomorphism between literal and metaphorical uses of source-domain vocabulary very straightforwardly by looking at synonymy and antonymy. Deignan argues that these lexical relations should be transferred to the target domain, such that, for example, metaphorical meanings of cold and hot should also be found for cool and warm respectively, since their literal meanings are very similar. Likewise, metaphorical hot and cold should encode opposites in the same way they do in their literal uses.

Let us replicate Deignans study using the BNC Baby. To keep other factors equal, let us focus on attributive uses of adjectives that modify target domain nouns (as in cold facts), or nouns that are themselves used metaphorically (as in “The project went into cold storage” meaning work on it ceased). Deignan focuses on the base forms of these adjectives, let us do the same. She also excludes “highly fixed collocations and idioms” because their potential metaphorical origin may no longer be transparent – let us not follow her here, as we can always identify and discuss such cases after we have extracted and tabulated our data.

Deignan does not explicitly present an annotation scheme, but she presents dictionary-like definitions of her categories and extensive examples of her categorization decisions that, taken together, serve the same function. Her categories differ in number (between four and ten) and semantic granularity across the four words, let us design a stricter annotation scheme with a minimal number of categories.

Let us assume that survey of the dictionaries already used in Case Study 9.2.1.2 yields the following major metaphor categories:

- \(\mathrm{activity}\), with the metaphors \(\mathrm{high \space activity \space is \space heat}\) and \(\mathrm{low \space activity \space is \space coldness}\), as in cold/hot war, hot pursuit, hot topic, etc.). This sense is not recognized by the dictionaries, except insofar as it is implicit in the definitions of cold war, hot pursuit, cold trail, etc. It is understood here to include a sense of hot described in dictionaries as “currently popular” or “of immediate interest” (e.g. hot topic).

- \(\mathrm{affection}\), with the metaphors \(\mathrm{affection \space is \space heat}\) and \(\mathrm{indifference \space is \space coldness}\), as in cold stare, warm welcome, etc. This sense is recognized by all dictionaries, but we will interpret it to include sense connected with sexual attraction and (un)responsiveness, e.g. hot date.

- \(\mathrm{temperament}\), with the metaphors \(\mathrm{emotional \space behavior \space is \space heat}\) and \(\mathrm{rational \space behavior \space is \space coldness}\), as in cool head, cold facts, hot temper, etc. Most dictionaries recognize this sense as distinct from the previous one – both are concerned with emotion or its absence, but in case of the \(\mathrm{affection}\), the distinction is one between affectionate feelings and their absense, in the case of \(\mathrm{temperament}\) the distinction is one between behavior based on any emotion and behavior unaffected by emotion.

- \(\mathrm{synesthesia}\), a category covering uses described in dictionaries as “conveying or producing the impression of being hot, cold, etc.” in some sensory domain other than temperature, i.e. warm color, cold light, cool voice, etc.

- \(\mathrm{evaluation}\), with the (potential) metaphor \(\mathrm{positive \space things \space have \space a \space temperature}\), as in a really cool movie, a cool person, a hot new idea, etc. This may not be a metaphor at all, as both uses are very idiomatic; in fact, hot in this sense could be included under activity or affection, and cool in this sense is presumably derived from temperament.

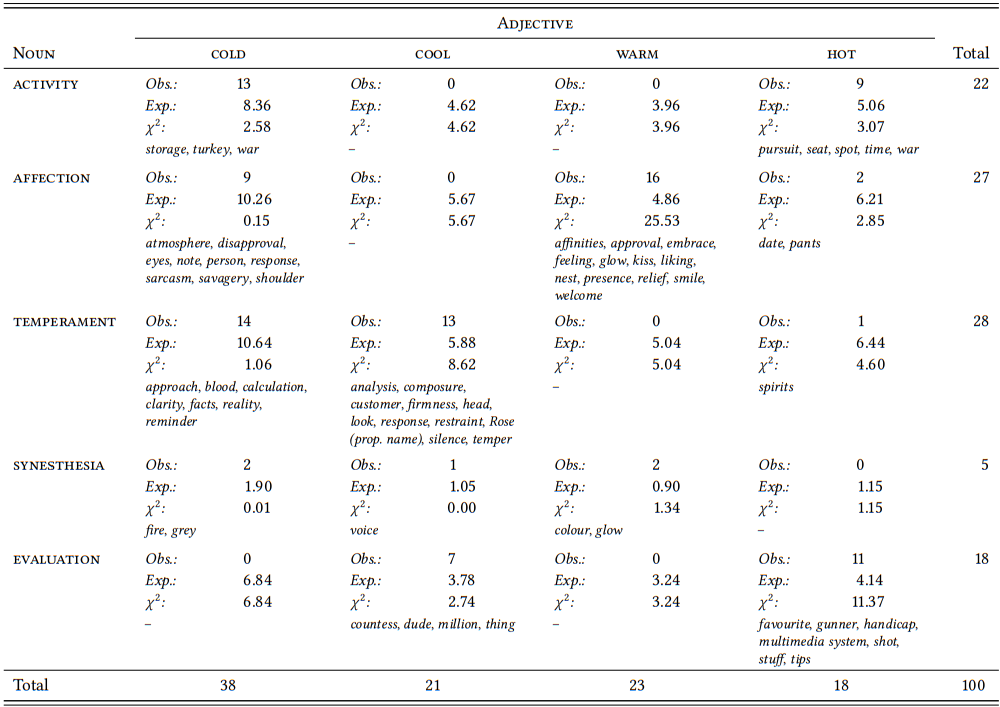

\(Table \text { } 11.1\) lists the token frequencies of the four adjectives with each of these broad metaphorical categories as well as all types instantiating the respective category. There is one category that does not show any significant deviations from the expected frequencies, namely the infrequently instantiated category \(\mathrm{synesthesia}\). For all other categories, there are clear differences that are unexpected from the perspective of conceptual metaphor theory.

The category activity is instantiated only for the words cold and hot and its absence for the other two words is significant. We can imagine (and, in a sufficiently large data set, find) uses for cool and warm that would fall into this category. For example, Frederick Pohl’s 1981 novel The Cool War describes a geopolitical situation in which political allies sabotage each other’s economies, and it is occasionally used to refer to real-life situations as well. But this seems to be a deliberate analogy rather than a systematic use, leaving us with an unexpected gap in the middle of the linguistic scale between hot and cold.

The category affection is found with three of the four words, but its absence for the word cool is statistically significant, as is its clear overrepresentation with warm. This lack of systematicity is even more unexpected than the one observed with activity: for the latter, we could argue that it reflects a binary distinction that uses only the extremes of the scale, for example because there is not enough of a potential conceptual difference between a cold war and a cool war. With

\(Table \text { } 11.1\): \(mathrm{temperature}\) metaphors (BNC Baby)

\(\mathrm{affection}\), in contrast, this explanation is not adequate, as the entire scale is used. It remains unclear, therefore, why warm should be so prominently used here, and why cool is so rare (it is possible: the dictionaries list examples like a cool manner, a cool reply).

With temperament, we find a partially complementary situation: again, three of the four words occur with this metaphor, including, again, the extreme points. However, in this case it is cool that is significantly overrepresented and warm that is significantly absent. A possible explanation would be that there is a potential for confusion between the metaphors affection is temperature and temperament is temperature, and so speakers divide up the continuum from cold to hot between them. However, this does not explain why cold is frequently used in both metaphorical senses.

The gaps in the last category, \(\mathrm{evaluation}\), are less confusing. As mentioned above, this is probably not a single coherent category and we would not expect uses to be equally disributed across the four words.

This case study demonstrates the use of corpus data to evaluate claims about conceptual structure. Specifically, it shows how a central claim of conceptual metaphor theory can be investigated (see the much more detailed discussion in Deignan (1999b).

11.2.1.2 Case study: Word forms in metaphorical mappings

Another area in which we might expect a large degree of isomorphism between literal and metaphorical uses of a word is the quantitative and qualitative distribution of word forms. In a highly intriguing study, Deignan (2006) investigate the metaphors associated with the source domain words flame and flames in terms of whether they occur in positively or negatively connoted contexts.

Her study is generally deductive in that she starts with an expectation (if not quite a full-fledged hypothesis) that there are frequently differences between the singular and the plural forms of a metaphorically used word with respect to connotation.

A cursory look at a few relatively randomly selected examples appears to corroborate this expression. More precisely, it seems that the singular form flame has positive connotations more frequently than expected (cf. 1), while the plural form flames has negative connotations more frequently than expected (cf. 2):

-

- [T]he flame of hope burns brightly here. (BNC AJD)

- Emilio Estevez, sitting on the sofa next to old flame Demi Moore... (BNC CH1)

-

- ...the flames of civil war engulfed the central Yugoslav republic. (BNC AHX)

- The game was going OK and then it went up in flames. (BNC CBG)

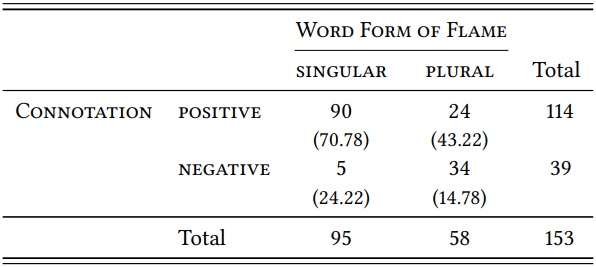

Deignan studies this potential difference systematically based on a sample of more than 1500 hits for flame/s in the Bank of English (a proprietary, non-accessible corpus owned by HarperCollins), from which she manually extracts all 153 metaphorical uses. These are then categorized according to their connotation. Deignan’s design thus has two nominal variables: \(\mathrm{Word \space Form \space of \space Flame}\) (with the variables \(\mathrm{singular}\) and \(\mathrm{plural}\)) and \(\mathrm{Connotation \space of \space Metaphor}\) (with the values \(\mathrm{positive}\) and \(\mathrm{negative}\)). She does not provide an annotation scheme for categorizing the metaphorical expressions, but she provides a set of examples that are intuitively quite plausible. \(Table \text { } 11.2\) shows her results (\(\chi^{2}\) = 53.98, df = 1, \(p\) < 0.001).

\(Table \text { } 11.2\): Positive and negative metaphors with singular and plural forms of flame (Deignan 2006: 117)

Clearly, metaphorical singular flame is used in positive metaphorical contexts much more frequently than metaphorical plural flames. Deignan tentatively explains this in relation to the literal uses of flame(s): a single flame is “usually under control”, and it may “be if use, as a candle or a burning match”. If there is more than one flame, we are essentially dealing with a fire – “flames are often undesired, out of control and very dangerous” (Deignan 2006: 117).

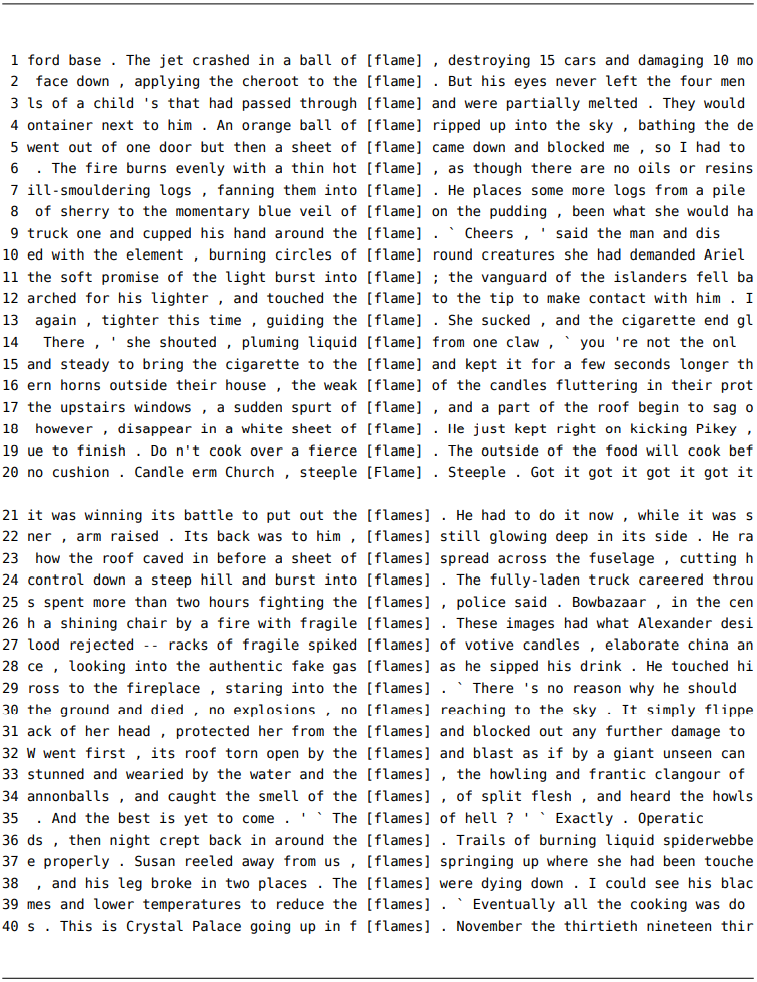

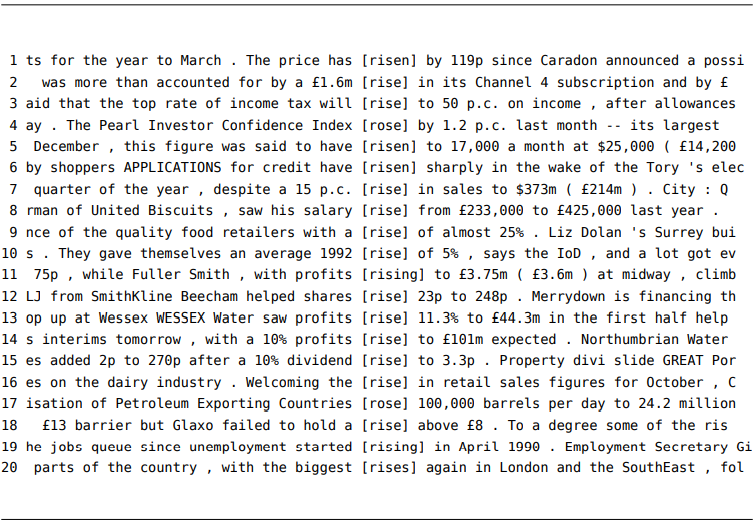

This explanation itself is of course a hypothesis about the literal use of singular and plural flame that must be tested separately. Deignan does not provide such a test, so let us do it here. Let us select a sample of 20 hits each for literal uses the singular and plural of flame(s) from the BNC (as mentioned above, Deignan’s corpus is not accessible, so we must hope that the BNC is roughly comparable). \(Figure \text { } 11.1\) shows the sample for singular (lines 1–20) and plural (21–40).

\(Figure \text { } 11.1\): Concordance of flame(s) (BNC, Sample)

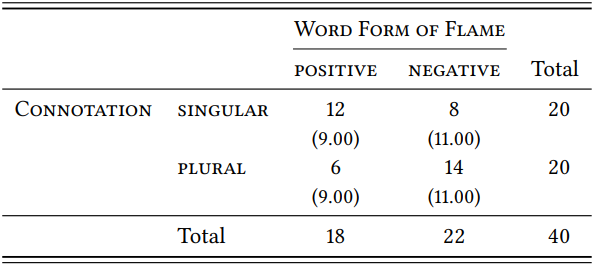

It is difficult to determine which hits should be categorized as positive and which as negative. Let us assume that any unwanted and/or destructive fire should be characterized as negative, and, on this basis, categorize lines 1, 3, 4, 5, 11, 14, 17, 18, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 and 40 as \(\mathrm{negative}\) and the rest as \(\mathrm{positive}\). This would give us the result in \(Table \text { } 11.3\) (if you disagree with the categorization, come up with your own and do the corresponding calculations).

\(Table \text { } 11.3\): Positive and negative contexts for literal uses of singular and plural forms of flame/s

It does seem that negative connotations are found more frequently with literal uses of the plural form flames than with literal uses of the singular form flame. Despite the small size of the sample used here, this difference only just fails to reach statistical significance (\(\chi^{2}\) = 3.64, df = 1, \(p\) = 0.0565). The difference would likely become significant if we used a larger sample. However, it is nowhere near as pronounced as in the metaphorical uses presented by Deignan. A crucial difference between literal and metaphorical uses may be that fire is inherently dangerous and so literal references to fire are more likely to be negative than metaphorical ones, that allow us to focus on other aspects of fire. Interestingly, however, most of the negative uses of singular flame occur in constructions like ball of flame, sheet of flame and spurt of flame, where flame could be argued to be a mass noun rather than a true singular form. If we remove these five uses, then the difference between singular and plural becomes very significant even in the now further reduced sample (\(\chi^{2}\) = 8.58, df = 1, \(p\) < 0.01).

Thus, Deignan’s explanation appears to be generally correct, providing evidence for a substantial degree of isomorphism between literal and figurative uses of (at least some) words. An analysis of more such cases could show whether this isomorphism between literal and metaphorical uses is a general principle (as the conceptual theory of metaphor as Lakoff (1993) suggests it should be.

This case study demonstrates first, how to approach the study of metaphor starting from source-domain words, and, second, that such an approach may be applied not just descriptively, but in the context of answering fundamental questions about the nature of metaphor.

11.2.1.3 Case study: The impact of metaphorical expressions

A slightly different example of a source-domain oriented study is found in Stefanowitsch (2005), which investigates the relationship between metaphorical and literal expressions hinted at at the end of the preceding case study. The aim of the study is to uncover evidence for the function of metaphorical expressions that have literal paraphrases, such as [dawn of NP] in examples like (3a), which is seemingly equivalent to the literal [beginning of NP] in (3b):

-

- [I]t has taken until the dawn of the 21st century to realise that the best methods of utilising . . . our woodlands are those employed a millennium ago. (BNC AHD)

- Communal life survived until the beginning of the nineteenth century and traditions peculiar to that way of life had lingered into the present. (BNC AEA)

Other examples studied in Stefanowitsch (2005) are in the center/heart of, at the center/heart of and a(n) increase/growth/rise in. The studies have two nominal variables: the independent variable is \(\mathrm{Metaphoricity \space of \space Pattern}\) (whose values are pairs of patterns like the one illustrated in examples (3a, b)), the dependent variable is \(\mathrm{Noun}\) (whose values are the nouns in the NP slot provided by these patterns. Methodologically, this corresponds to a differential collexeme analysis (Chapter 8, Case Study 8.2.2.2).

The studies are deductive in that they aim to test the hypothesis that metaphorical language serves a cognitive function and that for each pair of patterns investigated, the metaphorical variant should be used with nouns referring to more complex entities. The construct \(\mathrm{complexity}\) is operationalized in the form of axioms derived from gestalt psychology, such as the following:

Concepts representing entities that have a simple shape and/or have a clear boundary are less complex than those representing entities with complex shapes or fuzzy boundaries (because they are more easily delineable). This follows from the gestalt principles of closure and simplicity (Stefanowitsch 2005: 170).

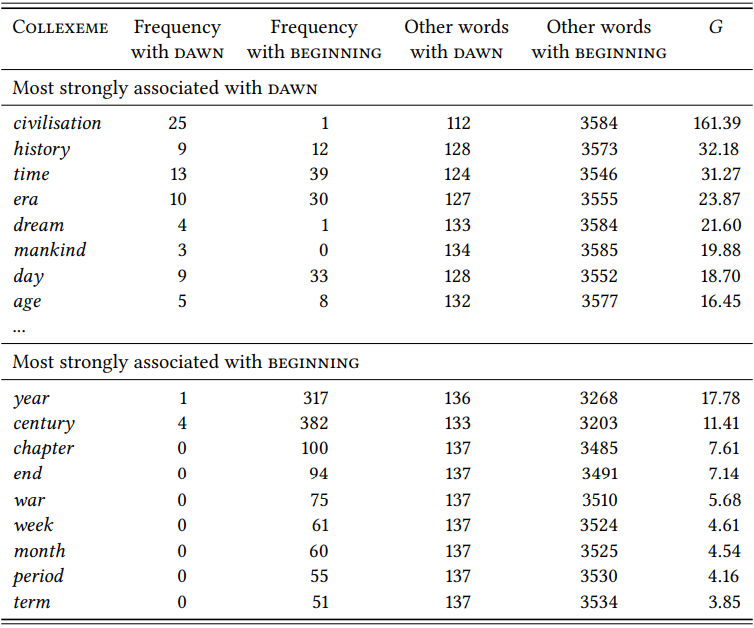

For each pair of expressions, the differential collexemes are identified and the resulting lists are compared against these axiomatic assumptions. Let us illustrate this using the pattern the dawn/beginning of NP. A case insensitive query for the \(\text {string dawn}\) or \(\text {beginning}\), followed by of, followed by up to three words that are not a noun, followed by a noun yields the results shown in \(Table \text { } 11.4\) (they are very similar to those based on a more careful manual extraction in Stefanowitsch 2005).

Table 11.4: Differential collexemes of beginning of NP and dawn of NP (BNC)

Unsurprisingly, both expressions are associated almost exclusively with words referring to events and time spans (or, in some cases, with entities that exist through time, like mankind, or that we interact with through time, like chapter). Crucially, most of the nouns associated with the literal beginning of refer to time spans with clear boundaries and a clearly defined duration (year, century, etc.), while those associated with the metaphorical dawn of refer to events and time spans without clear boundaries or a clear duration (civilization, time, history, age, era, culture). The one apparent exception is day, but this occurs exclusively in literal uses of dawn of, such as It was the dawn of the fourth day since the murder (BNC CAM). This (and similar results for other pairs of expressions) are presented in Stefanowitsch (2005) as evidence for a cognitive function of metaphor.

In a short discussion of this study, Liberman (2005) notes in passing that even individual decades and centuries may differ in the degree to which they prefer beginning of or dawn of : using internet search engines, he shows that dawn of the 1960s is more probable than dawn of the 1980s compared to beginning of the 1960s/1980s, and that dawn of the 21st century is more probable than dawn of the 18th century compared to beginning of the 18th/21st century. He rightly points out that this seems to call into question the properties of boundedness and well-defined length that Stefanowitsch (2005) appeals to, since obviously all decades/ centuries are equally bounded.

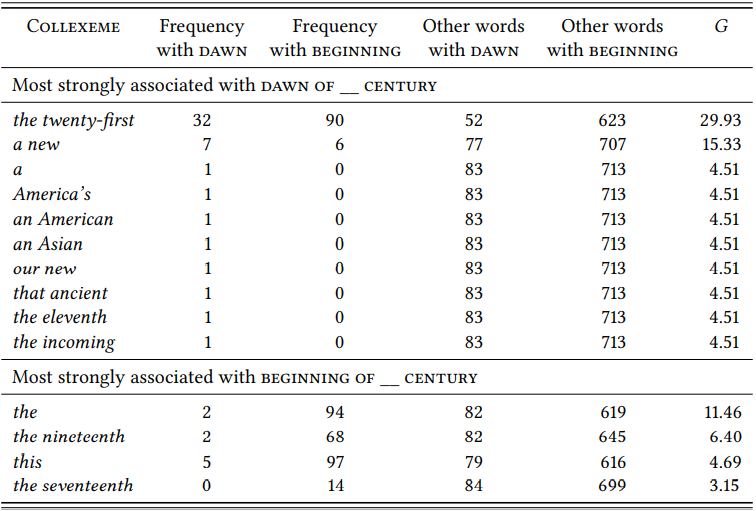

Since search engine frequency data are notoriously unreliable, let us replicate this observation in a large corpus, the 400+ million word Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). The names of decades (such as 1960s or sixties) occur too infrequently with dawn of in this corpus to say anything useful about them, but the names of centuries are frequent enough for a differential collexeme analysis.

\(Table \text { } 11.5\) shows the percentage of dawn of for the past ten centuries (spelling) variants of the respective centuries, such as 19th century, nineteenth century, etc.) as well as spelling errors were normalized to the spelling shown in this table.

There are clear differences between the centuries associated with \(\mathrm{dawn}\) and those associated with \(\mathrm{beginning}\): the literal expression is associated with the past (nineteenth, seventeenth (just below significance)), while the metaphorical expression, as already observed by Liberman, is associated with the twenty-first century, i.e., the future (the expressions a new, our new and the incoming also support this). I would argue that this does point to a difference in boundedness and duration. While all centuries are objectively speaking, of the same length and have the same clear boundaries, it seems reasonable to assume that the past feels more bounded than the future because it is actually over, and we can imagine it in its entirety. In contrast, none of the speakers in the COCA will live to see the end of the 21st century, making it conceptually less bounded to them.

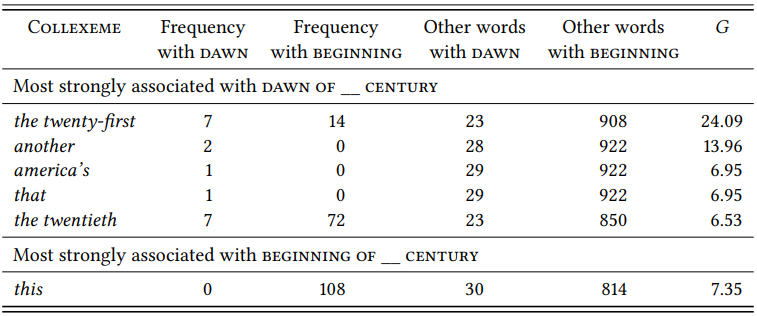

If this is true, then we should be able to observe the same effect in the past: When the twentieth century was still the future, it, too, should have been associated with the metaphorical dawn of. Let us test this hypothesis using the Corpus of Historical American English, which includes language from the early nineteenth to the very early twenty-first century – in a large part of the corpus, the twentieth century was thus entirely or partly in the future. \(Table \text { } 11.6\) shows the differential collexemes of the two expressions in this corpus.

\(Table \text { } 11.5\): Differential collexemes of dawn/beginning of __ century (COCA)

\(Table \text { } 11.6\): Differential collexemes of dawn/beginning of __ century (COHA)

As predicted, the twentieth century is now associated with the metaphorical expression (as is the twenty-first). In addition, there is the expression America’s century in both corpora, and an American and an Asian in COCA. These, I would argue, do not refer to precise centuries but are to be understood as labels for eras. In sum, I would conclude that the idea of boundedness accounts for the apparent exceptions too, at least in the case of centuries, supporting a cognitive function of metaphor.

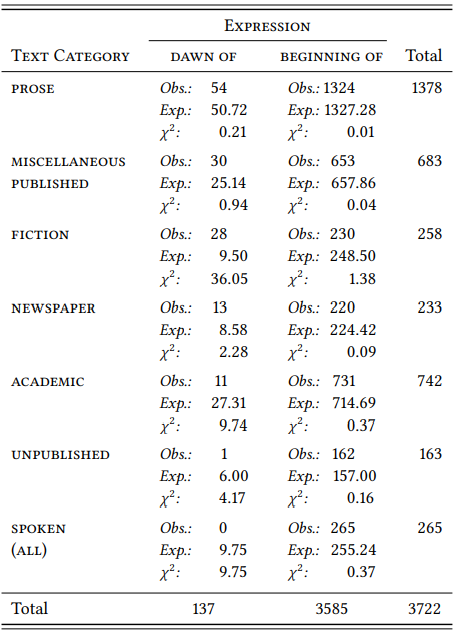

Even if we agree with this conclusion in general, however, it does not preclude a more literary, rhetorical function for metaphor in addition: while some of the expression pairs investigated in Stefanowitsch (2005) are fairly neutral with respect to genre or register, metaphorical dawn of intuitively has a distinctly literary flavor. To conclude this section, let us check the distribution of the hits for the query outlined above across the text categories defined in the BNC. \(Table \text { } 11.7\) shows the results (note that the categories Spoken Conversation and Spoken Other from the BNC have been collapsed into a single category here).

It is very obvious that the metaphorical expression the dawn of is significantly overrepresented in the text category \(\mathrm{fiction}\) and underrepresented in the text categories \(\mathrm{academic}\) and \(\mathrm{spoken}\), corroborating the intuition about the literary-ness of the expression. Within this text category, of course, it may well have the cognitive function attributed to it in Stefanowitsch (2005).

This case study demonstrates use of the differential collexeme analysis (and thus of collocational methods in general) that goes beyond associations between words and other elements of structure and instead uses words and grammatical patterns as ways of investigating semantic associations. Direct comparisons of literal and metaphorical language are rare in the research literature, so this remains a potentially interesting field of research. The study also demonstrates that the distribution of particular metaphorical expressions across varieties, which can easily be determined in corpora that contain the relevant metadata, may shed light on the function of those expressions (and of metaphor in general).

11.2.2 Target domains

As discussed in Chapter 4, there are two types of metaphorical utterances: those that could be interpreted literally in their entirety (like the example I am burned up from Lakoff & Kövecses 1987: 203), and those that contain vocabulary from both the source and the target domain (like He was filled with anger). Stefanowitsch (2004; 2006c) refers to the latter as metaphorical patterns, defined as follows:

A metaphorical pattern is a multi-word expression from a given source domain (SD) into which one or more specific lexical item from a given target domain (TD) have been inserted (Stefanowitsch 2006c: 66).

\(Table \text { } 11.7:\) The expressions dawn of and beginning of by text category (BNC)

In the example just cited, the multi-word source-domain expression would be [NPcontainer be filled with NPsubstance], the source domain would be that of substances in containers. The target domain word that has been inserted in this expression is anger, yielding the metaphorical pattern [NPcontainer be filled with NPemotion]. The metaphors instantiated by this pattern include “an emotion is a substance” and “experiencing an emotion is being filled with a substance”.

A metaphorical pattern analysis of a given target domain (like ‘anger’) thus proceeds by selecting one or more words that refer to (or are inherently connected with) this domain (for example, the word anger, or the set irritation, annoyance, anger, rage, fury, etc.) and retrieve all instances of this word or set of words from a corpus. The next step consists in identifying all cases where the search term(s) occur in a multi-word expression referring to some domain other than emotions. Finally, the source domains of these expressions are identified, 41111 Metaphor giving us the metaphor instantiated by each metaphorical pattern. The patterns can then be grouped into larger sets corresponding to metaphors like “emotions are substances”.

11.2.2.1 Case study: Happiness across cultures

Stefanowitsch (2004) investigates differences in metaphorical patterns associated with happiness in American English and its translation equivalent Glück in German. The study finds, among other things, that the metaphors \(\mathrm{attempt \space to \space achieve \space happiness \space is \space a \space search/pursuit}\) and \(mathrm{causing \space happiness \space is \space a \space transaction}\) are instantiated more frequently in American English than in German. The question, raised but not addressed in Stefanowitsch (2004), is whether this is a linguistic difference or a cultural difference. The word Glück is a close translation equivalent of happiness, but the meaning of these two words is not identical. For example, as Goddard (1998) argues and Stefanowitsch (2004) shows empirically (cf. Case Study 11.2.2.2), the German word describes a more intense emotion than the English one. This may have consequences for the metaphors a word is associated with. Alternatively, the emotional state described by both Glück and happiness may play a different role in German vs. American culture, for example, in regard to beliefs about whether and how one can actively try to cause or achieve it. In order to answer this question, we need to compare metaphorical patterns associated with happiness in different English-speaking cultures (or patterns associated with Glück in different German-speaking ones).

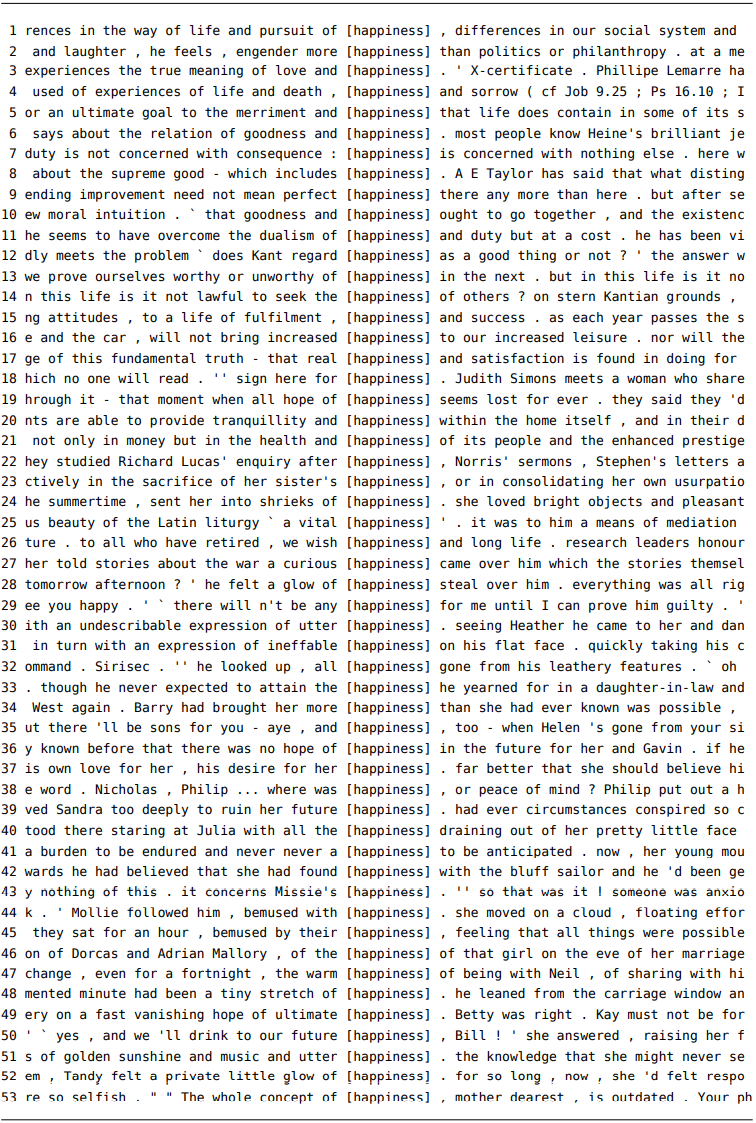

Let us attempt to do this, focusing on the two metaphors just mentioned but discussing others in passing. In order to introduce the method of metaphorical pattern analysis, let us limit the study to small samples of language, which will allow us to study the relevant concordances in detail. This will make it less probable that we will find statistically significant differences, so let us treat the following as an exploratory pilot study. Given how frequently we have compared British and American English in this book, these two varieties may seem an obvious place to start, but the two cultures may be too similar, and the word happiness happens to be too infrequent in the BROWN corpus anyway. Let us compare British English (the LOB corpus) and Indian English (the Kolhapur corpus constructed along the same categories) instead. Figure 11.2 shows all hits of the query \(\langle\text { [word="happiness"}\% \text{c}]\rangle\).

The very first line contains an example of one of the \(\mathrm{search/pursuit}\) metaphor, namely the metaphorical pattern [pursuit of NPEMOT]. If we go through the entire concordance, we find three additional patterns instantiating this metaphor, namely [seek NPEMOT] (line 14), [NPEMOT be found in Ving] (line 17) and [NPEXP

\(Figure \text { } 11.2\): Concordance of happiness (LOB)

find NPEMOT] (line 42), with NPEXP indicating the slot for the noun referring to the experiencer of the emotion. Note that, as is typical in metaphorical pattern analysis, the patterns are generalized with respect to the slot of the emotion noun (we could find the same patterns with other emotions), and they are relatively close in form to the actual citation. We could subsume the passive in line 17 under the same pattern as the active in line 42, of course, but there might be differences across emotion terms, varieties, etc. concerning voice (and other formal aspects of the pattern), and there is little gained by discarding this information.

The \(\mathrm{transfer}\) metaphor is also instantiated a number of times in the concordance, namely as [NPSTIM bring NPEMOT] (lines 16 and 42), and [NPSTIM provide NPEMOT] (line 20).

Additional clear cases of metaphorical patterns are [glow of NPEMOT] (lines 28 and 53) and [warm NPEMOT] (line 47), which instantiate the metaphor \(\mathrm{happiness \space is \space warmth}\), and [NPEMOT drain out of NPEXP’s face] (line 40), which instantiates \(\mathrm{happiness \space is \space a \space liquid \space filling \space the \space experiencer}\). In other cases, it depends on our judgment (which we have to defend within a given research design) whether a hit constitutes a metaphorical pattern. For example, do we want to analyze [NPSTIM’s NPEMOT] (lines 23 and 43) and [PRON.POSS.STIM NPEMOT] (lines 37, 39, 45, 50) as \(\mathrm{happiness \space is \space a \space possessed \space object}\), or do we consider the possessive construction to be too abstract semantically to be analyzed as metaphorical? Similarly, do we analyze [NPSTIM engender NPEMOT] (line 2) as an instance of \(\mathrm{happiness \space is \space an \space organism}\), based on the etymology of engender, which comes from Latin generare beget and was still used for organisms in Middle English (cf. Chaucer’s ...swich licour, / Of which vertu engendred is the flour)? You might want to think about these and other cases in the concordance, to get a sense of the kind of annotation scheme you would need to make such decisions on a principled, replicable basis.

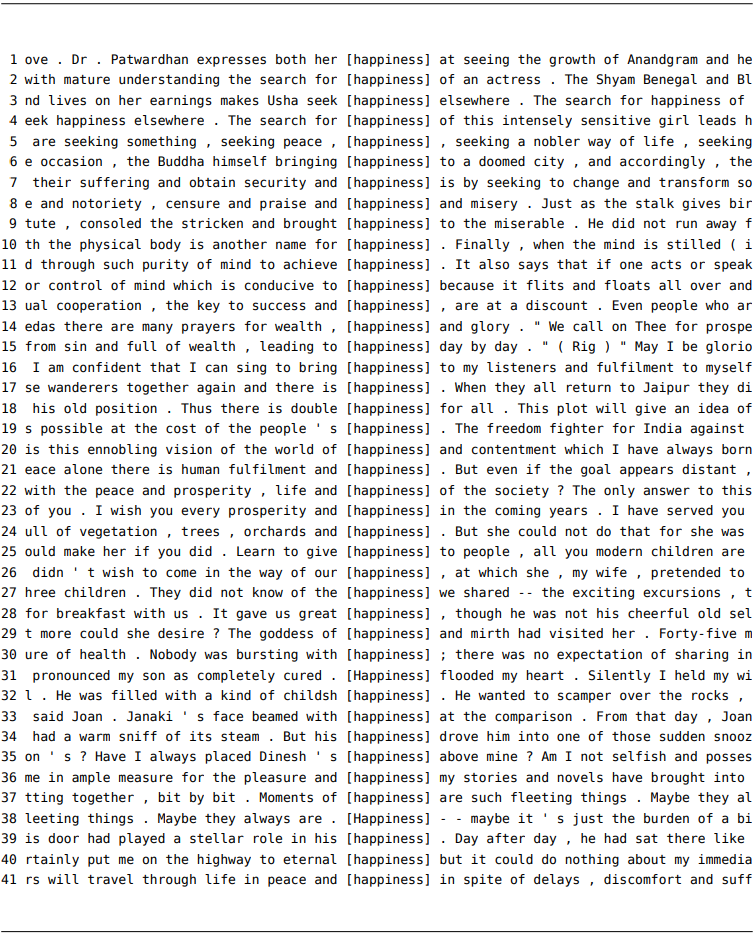

For now, let us turn to Indian English. \(Table \text { } 11.3\) shows the hits for the query \(\langle\text { [word="happiness"}\% \text{c}]\rangle\) in the Kolhapur corpus. Here, 35 hits for the phrase harmonious happiness have been removed, because they all came from one text extolling the virtues of the principle of harmonious happiness (17 hits), (moral) standard of harmonious happiness (15 hits), (moral) good of harmonious happiness (2 hits) or nor of harmonious happiness (1 hit). This text is obviously very much an outlier, as it contains almost as many hits as the entire rest of the corpus combined, and as the hits are extremely restricted in their linguistic behavior. To discard them might not seem ideal, but to include them would be even less so.

Again, the \(\mathrm{search}\) metaphor is instantiated several times in the concordance: we find [search for NPEMOT] (lines 2 and 4) and [NPEXP seek NPEMOT] (lines 3 and 5). They all seem to be from the same text, so similar considerations apply

\(Figure \text { } 11.3\): Concordance of happiness (Kolhapu)

as in the case of the principle/standard of harmonious happiness. We also find the transfer metaphor quite strongly represented: [NPSTIM bring NPEMOT] (lines 6, 9, 16), [NPEXP obtain NPEMOT] (line 7), [NPSTIM give NPEMOT] (lines 25, 28) and [NPEXP share NPEMOT] (line 27).

Again, there are other clear cases of metaphor, such as [NPEXP burst with NPEMOT] (line 30), [NPEMOT flood NPEXP’s heart] (line 31), and [NPEXP be filled with NPEMOT] (line 32) (again, they seem to be from the same text).

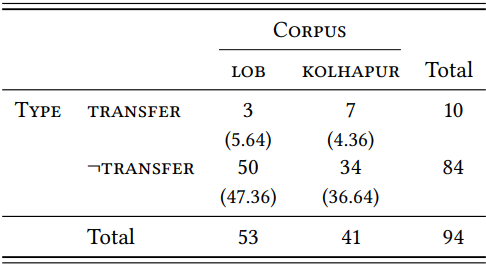

Comparing the metaphors we set out to investigate, we see that the \(\mathrm{pursuit}\) and \(\mathrm{search}\) metaphors are fairly evenly distributed across the two varieties, with no significant difference even on the horizon. The \(\mathrm{transfer}\) metaphor, in contrast, shows clear differences, and as \(Table \text { } 11.8\) shows, this difference is almost significant even in our small sample (\(\chi^{2}\) = 3.17, df = 1, \(p\) = 0.075). This would be an interesting difference to look at in a larger study, especially since the two varieties differ not only in the token frequency of this metaphor, but also in the type frequency – the LOB corpus contains only two different patterns instantiating this metaphor, the Kolhapur corpus contains four.

\(Table \text { } 11.8\): \(\mathrm{causing \space happiness \space is \space a \space transfer\) in two corpora (LOB, Kolhapur)

This case study demonstrates the basic procedure of Metaphorical Pattern Analysis and some of the questions raised by the need to categorize corpus hits. It also shows that even a small-scale study of such patterns may provide interesting results on which we can build hypotheses to be tested on larger data sets. Finally, it shows that there may well be differences between cultures in the metaphorical patterns and the overarching metaphors they instantiate (cf. e.g. Rojo López & Orts Llopis 2010, Rojo López 2013 and Ogarkova & Soriano Salinas 2014 for cross-linguistic comparisons and Dıaz-Vera & Caballero 2013 ́ , Dıaz-Vera 2015 ́ and Güldenring 2017 for comparisons across different varieties of English; cf. also Tissari 2003; 2010 for comparisons across time periods within one language).

11.2.2.2 Case study: Intensity of emotions

Whether we start from the source domain or from the target domain, the extraction of metaphorical patterns from large corpora typically requires time-consuming manual annotation. However, if we are interested in specific metaphors, we can speed up the extraction significantly, by looking for utterances containing vocabulary from the source and target domains we are interested in. For example, Martin (2006) compiles lists of words from two domains (such as \(\mathrm{war}\) and \(\mathrm{commercial \space activity}\) and then searches a large corpus for instances where items from both lists co-occur in a particular span.

We can take this basic idea and apply it in a linguistically slightly more conservative way to target-item oriented versions of metaphorical pattern analysis. Instead of searching for co-occurrence in a span, let us construct a set of structured queries that would find metaphorical patterns instantiating a given metaphor. As mentioned in Case Study 11.2.2.1, the word happiness and its German translation equivalent Glück may differ in the intensity of the emotion they refer to. In Stefanowitsch (2004), this hypothesis is tested by investigating metaphors that plausibly reflect such a difference in intensity. Specifically, it is shown that while both happiness and Glück are found with metaphors describing an emotion as a substance in a container (the experiencer), Glück is found significantly more frequently with metaphors describing the experiencer as a container that disintegrates because it cannot withstand the pressure of the substance. The same difference is found within English between the words happiness and joy.

Let us investigate these metaphors with respect to frequent basic emotion terms in English, to see whether there are general differences between emotions with respect to metaphorical intensity. Stefanowitsch (2006c) lists the metaphorical patterns for five English emotion terms, categorized into general metaphors. Combining all patterns occurring with at least one emotion noun, the patterns in (4) are identified or the metaphor \(\mathrm{emotions \space are \space a \space substance \space in \space a \space container}\) with an experiencer is a container (instead of the experiencer themselves, the patterns may also refer to their heart, face, eyes, mind, voice, etc.):

-

- NPEMOT fill NPEXP

- NPSTIM fill NPEXP with NPEMOT

- NPEXP fill (up) with NPEMOT

- NPEXP be filled with NPEMOT

- NPEXP be full of NPEMOT

- NPEXP be(come) filled with NPEMOT

- NPEMOT seep into NPEXP

- NPEMOT spill into NPEXP

- NPEMOT flood through NPEXP

Let us ignore the patterns in (4g–i), which occurred only once each in Stefanowitsch (2006c). The rest then form a set of expressions with relatively simple structures that we can extract using the following queries (shown here for the noun happiness):

-

- \(\text{[hw="full"] [hw="of"] []{0,2} [word="happiness"%c]}\)

- \(\text{[hw="(fill|filled)"] [hw="with"] []{0,2} [word="happiness"%c]}\)

- \(\text{[word="happiness"%c] [pos=".*(VB|VD|VH|VM).*"] [pos=".*AV0.*"] [hw="fill" & pos=".*VV.*"]}\)

The paper also lists a number of metaphorical patterns that describe an increasing pressure, e.g. [NPEMOT build inside NPEXP] or an overflowing, e.g. [NPEXP brim over with NPEMOT], but let us focus on those patterns that describe a sudden failure to contain the substance. These are listed in 6.:

-

- burst/outburst/explosion of NPEMOT

- NPEMOT burst in/through NPEXP

- NPEMOT burst (out)

- NPEMOT erupt/explode

- NPEMOT blow up

- NPEXP burst/erupt/explode with NPEMOT

- explosive NPEMOT

- volcanic NPEMOT

We can extract these patterns using the following queries (shown, again, for happiness):

-

- \(\text{[word="happiness"%c & pos=".*NN.*"] [hw="(burst|erupt| explode)" & pos=".*VV.*"]}\)

- \(\text{[word="happiness"%c & pos=".*NN.*"] [hw="(blow)" & pos=".*VV.*"][word="up"%c]}\)

- \(\text{[hw="(explosive|eruptive|volcanic)"] [word="happiness"%c & pos=".*NN.*"]}\)

- \(\text{[hw="(burst|erupt|explode)" & pos=".*VV.*"] [word="(in| with)"%c] [word="happiness"%c & pos=".*NN.*"]}\)

- \(\text{[hw="(outburst|burst|eruption|explosion)"] [word="of"%c] [word="happiness"%c & pos=".*NN.*"]}\)

We are now searching for combinations of a target-domain item with specific source domain items in specific structural configurations. In doing so, we will reduce recall compared to a manual extraction, but the precision is very high, allowing us to query large corpora and to work with the results without annotating them manually.

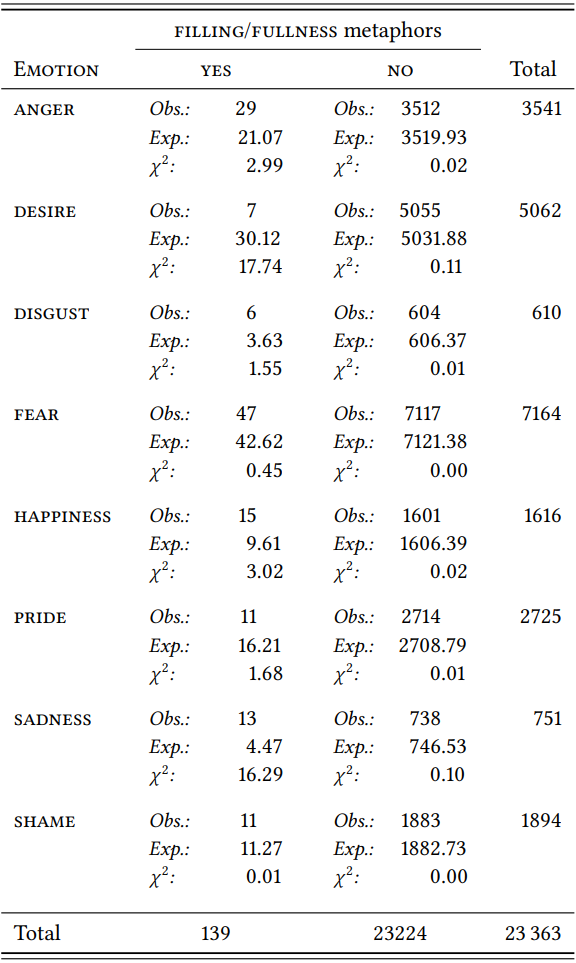

Let us apply both sets of queries to the basic emotion nouns anger, desire, disgust, fear, happiness, pride, sadness, shame. \(Table \text { } 11.9\) shows the tabulated results for the queries in (5) compared against the overall frequency of the respective nouns in the BNC.

There are two emotion nouns whose frequency in these metaphorical patterns deviates from the expected frequency: desire is described as a substance in a container less frequently than expected, and sadness is more frequently than expected. It is an interesting question why this should be the case, but it is not plausibly related to the intensity of the respective emotions.

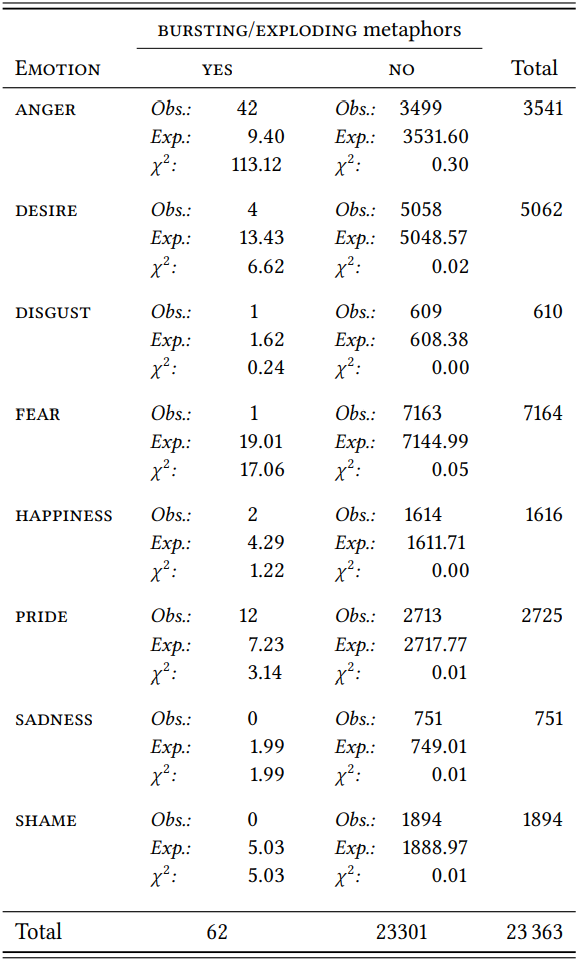

\(Table \text { } 11.10\) shows the tabulated results for the queries in (7) compared against the overall frequency of the respective nouns in the BNC.

Two emotion nouns occur with the \(\mathrm{bursting}\) metaphors noticeably more frequently than expected, namely anger and pride (the latter marginally significantly); three occur noticeably less frequently, desire, fear and shame. Again, this does not seem to be related to the intensity of the emotion – fear or desire can be just as intense as anger or pride. Instead, it seems to be related to the likelihood that the emotion will be outwardly visible, for example, by resulting in a particular kind of behavior toward others. Again, desire is an exception, it may be that it does not participate in container metaphors at all.

This case study demonstrates how central metaphors for a given target domain can be identified by searching for combinations of words describing (aspects of) the source and the target domain in question. It also shows that these metaphors can be associated to different degrees with different words within a given target domain (cf. e.g. Stefanowitsch 2006c, Turkkila 2014). It is unclear to what extent this lexeme specificity of metaphorical mappings supports or contradicts current cognitive theories of metaphor, so it is potentially a very interesting area of research

\(Table \text { } 11.9\): The metaphor \(\mathrm{emotions \space are \space a \space substance \space filling \space the \space experiencer}\) (BNC)

Table 11.10: The metaphor \(\mathrm{emotions \space are \space a \space substance \space bursting \space the \space experiencer}\) (BNC)

11.2.3 Metaphor and text

11.2.3.1 Case study: Identifying potential source domains

If we are interested in questions relating to a particular source domain, as in Section 11.2.1, or to a particular target domain, as in Section 11.2.2, our first task is to define a representative set of lexical items to query. This set may be dictated by the hypothesis we are planning to test, or we may, in more exploratory studies, assemble it on the basis of thesauri or words and patterns identified in previous studies. If, on the other hand, we are interested in source domains associated with a particular target domain, matters are more complicated. We can start by selecting a set of target-domain items and then identify all source domains in the metaphorical patterns of these items, but while this will tell us something about these items, it does not tell us much about the target domain as a whole. Or we can identify the source domains manually, which restricts the amount of data we can reasonably process.

Partington (1998) suggests a promising solution to this problem: If we apply a keyword analysis (cf. Chapter 10) to a thematic corpus dealing with the target domain in question, then the dominant source domains in that target domain should be visibly represented among the keywords. Thus, searching the results for items that do not, in their literal meaning, belong to the target domain should identify items that ar used metaphorically in the target domain.

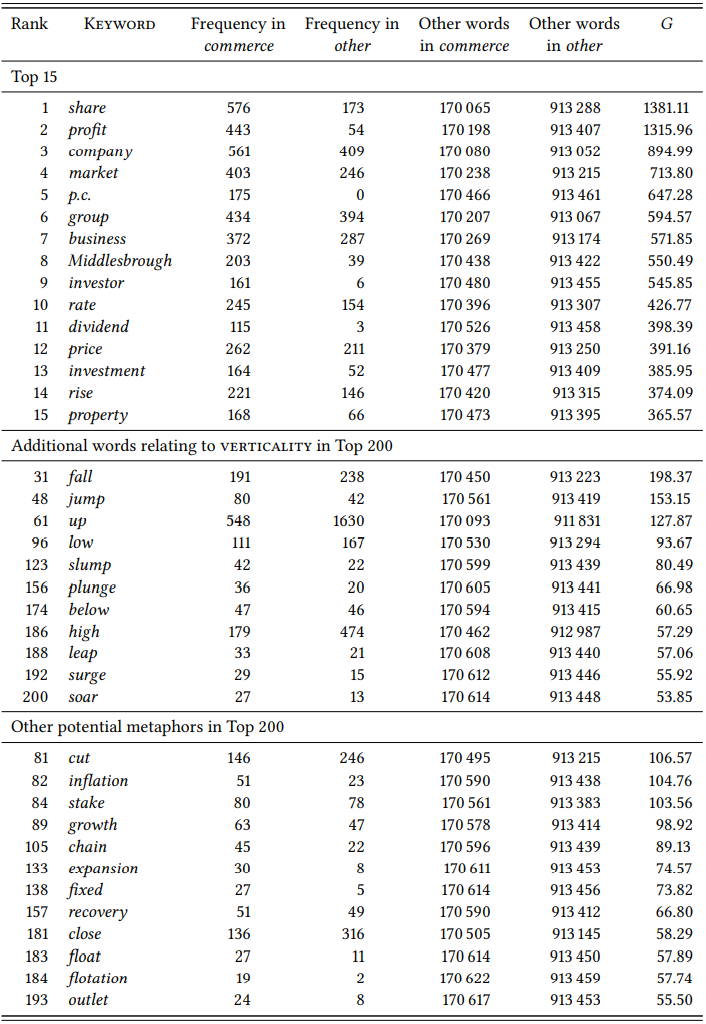

To demonstrate this method, let us define a subcorpus for the domain \(\text{economy}\) in the BNC Baby. This is easiest done by using the meta-information supplied by the corpus makers, which includes the category “commerce” as a subcategory of “newspaper” (cf. Table 2.2 in Chapter 2). Let us determine the keywords in this subcorpus compared to the rest of the \(\text{newspaper}\) subcorpus (excluding the \(\text{spoken}\), \(\text{fiction}\) and \(\text{academic}\) subcorpora, in order to reduce the number of keywords that are typical for newspaper language in general). \(Table \text{ } 11.11\) shows selected results of a keyword analysis of these files.

As expected, most of the strongest keywords for the subcorpus are directly related to the domain of economics. Among the Top 15 (shown in the first part of the table), only two are not directly related to this domain: the proper name Middlesbrough and the word rise. The keyness of the former is due to the fact that one of the files in the BNC Baby \(\text{commercial}\) subcorpus is from the Northern Echo, a regional newspaper covering County Durham and Teesside – Middlesbrough is the largest town in this region and is thus mentioned frequently, but it is not generally an important town, so it is hardly mentioned outside of this text. The keyness of the latter is more interesting, as it is the kind of word we are looking for: its literal meaning, ‘motion from a lower to a higher position’, would

\(Table \text { } 11.11\): Selected keywords from the newspaper subcategory \(\mathrm{commerce}\) (BNC Baby)

not be expected to be particularly central to the domain of economics. More interestingly, there are 11 additional words from the domain of ‘vertical motion’ among the Top 200 keywords, making it the largest single semantic field other than ‘economy’ (see second part of the table). There are only 12 other words whose literal meaning is not directly related to economy, listed in the third part of the table, from source domains such as ‘increase in size’ (inflation, growth, expansion), ‘health’ (recovery) and ‘bodies of water’ (float(ation), outlet).

This suggests that ‘vertical motion’ is a central source domain in the domain of economics, which we can now study by querying the respective keywords as well as other words from this domain (which we could get from a thesaurus). As an example, consider the concordance of the lemma rise in \(Figure \text { } 11.4\) (a random sample of 20 hits from the 221 hits in the \(\mathrm{commerce}\) section in the BNC Baby).

\(Figure \text{ } 11.4\): A concordance of the wordform rise in \(\mathrm{commerce}\) texts (BNC Baby, sample)

First, the concordance corroborates our suspicion that rise is not used literally in the domain of economics. All 20 hits refer not to vertical motion, but to an increase in quantity, i.e., they instantiate the metaphor \(\mathrm{more \space is \space up}\). This is true both of verbal uses (in lines 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 11, 12, 13, 17, and 19) and to the nominal uses in the remaining lines. Second, the nouns in the surrounding context show where this metaphor is applied, namely overwhelmingly to genuinely economic concepts like prices, tax rates, salaries, sales, dividends, profits, shares, etc.

The results of such a keyword analysis can now be used as a basis for all kinds of studies. For example, we may simply be interested in describing frequent metaphorical patterns in the data (say, in the context of teaching English for Special Purposes); some very noticeable examples are [riseN in NP] (lines 2, 7, 16) and [see NP riseV] (lines 8, 13), or [hold a riseN] (line 18).

Or we may be interested in the kind of research question discussed in Case Study 11.2.1.1, i.e. in whether literal synonyms and antonyms of rise are mapped isomorphically onto the domain of economics (the fact that jump, surge and soar as well as fall, slump and plunge are among the top 200 keywords certainly suggests they are.

Or we may be interested in the kind of research question discussed in Case Study 11.2.1.3, i.e. in what, if any, differences there are between the metaphorical pattern [rise in NP] and its literal equivalent [increase in NP]. For example, a query of the BNC for (8) results in 84 hits for rising cost(s) as opposed to 34 hits for increasing cost(s) and 7 hits for rising profit(s) as opposed to 12 hits for increasing profit(s):

- \(\text{[word="(rising|increasing)"%c] [word="(cost|profit)s?"%c]}\)

It is left as an exercise for the reader to test this distribution for significance using the \(\chi^{2}\) test or a similar test (but use a separate sheet of paper, as the margin of this page will be too small to contain your calculations). If more such differences can be found, this might suggest that the metaphor “increase in quantity is upward motion” is associated more strongly with spending money than with making money.

This case study demonstrates that central metaphors for a given target domain can be identified by applying a keyword analysis to a specialized corpus of texts from that domain. The case study does not discuss a particular research question, but obviously, the method is useful in the context of many different research designs. Of course, it requires specialized corpora for the target domain under investigation. Such corpora are not available (and in some cases not imaginable) for all target domains, so the method works better for some target domains (such as \(\mathrm{economics}\)) than for others (like emotions).

11.2.3.2 Case study: Metaphoricity signals

Although metaphorical expressions are pervasive in all language varieties and speakers do not generally seem to draw special attention to their occurrence, 42511 Metaphor there is a wide range of devices that mark non-literal language more or less explicitly (as in metaphorically/figuratively speaking, picture NP as NP, so to speak/ say):

-

- ...the princess held a gun to Charles’s head, figuratively speaking... (BNC CBF)

- He pictures eternity as a filthy Russian bathhouse... (BNC A18)

- ...the only way they can deal with crime is to fight fire, so to speak, with fire. (BNC ABJ)

Wallington et al. (2003) investigate the extent to which these devices, which they call metaphoricity signals, correlate systematically with the occurrence of metaphorical expressions in language use. They find no strong correlation, but as they note, this may well be due to various aspects of their design. First, they adopt a very broad view of what constitutes a metaphoricity signal, including expressions like a kind/type/sort of, not so much NP as NP and even prefixes like super-, mini-, etc. While some or all of these signals may have an affinity to certain kinds of non-literal language, one would not really consider them to be metaphoricity signals in the same way as those in (9a–c). Second, they investigate a carefully annotated, but very small corpus. Third, they do not distinguish between strongly conventionalized metaphors, which are found in almost every utterance and are thus unlikely to be explicitly signaled, and weakly conventionalized metaphors, which seems more likely to be signaled explicitly a priori).

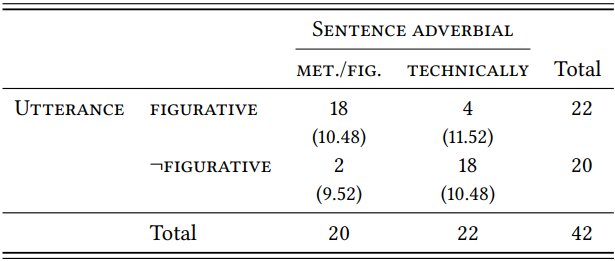

More restricted case studies are needed to determine whether the idea of metaphoricity signals is, in principle, plausible. Let us look at what is intuitively the clearest case of such a signal on Wallington et al.’s list: the sentence adverbials metaphorically speaking and figuratively speaking. As a control, let us use the roughly equally frequent sentence adverbial technically speaking, which does not signal metaphoricity but which can, of course, co-occur with (conventionalized) metaphors and which can thus serve as a baseline.

There are 22 cases of technically speaking in the BNC:

-

- Do you mind if, technically speaking, I resign rather than you sack me? (BNC A0F)

- Technically speaking as long as nobody was hurt, no injuries, no damage to the other vehicle, this is not an accident. (BNC A5Y)

- [T]echnically speaking, [...] if you put her out into the road she would have no roof over her head and we should have to take her in. (BNC AC7)

- You will have to be the builder, technically speaking. (BNC AM5)

- Technically speaking, the only difference between VHS and VHS-C is in the length of the tape in the cassette [...]. (BNC CBP)

- [U]nlike financial controllers, directors can, technically speaking, be held liable for negligence and consequently sued. (BNC CBU)

- Technically speaking [...], the unique formula penetrates the hair, enters the cortex and strengthens the hair bonds. (BNC CFS)

- As novelists, however, Orwell and Waugh evolve not towards each other but, technically speaking, in opposite directions. (BNC CKN)

- Under the Net [...] is technically speaking a memoir-novel [...], being composed as autobiography in the first person [...]. (BNC CKN)

- [T]he greater part of the works of art in the trade are technically speaking ‘second-hand goods’. (BNC EBU)

- [T]he listener feels uncomfortably voyeuristic at times (yes, yes, I know that technically speaking, a listener can’t be voyeuristic. (BNC ED7)

- Adulterers. That’s what they both were, technically speaking. (BNC F9C)

- Technically speaking, this [walk] will certainly lead to the semi-recumbent stone circle of Strichen in the district of Banff and Buchan [...]. (BNC G1Y)

- Richard was quite correct, as technically speaking they were all in harbour, in addressing them by the names of their craft. (BNC H0R)

- ‘What’s to stop you simply saying that my designs aren’t suitable [...]’ ‘Nothing, I suppose, technically speaking.’ (BNC H97)

- At least I was still a virgin, technically speaking. (BNC HJC)

- The mike concealed in the head of the figure is only medium-quality, technically speaking [...]. (BNC HTT)

- ‘Well, technically speaking [...] you are no longer in a position to provide him with employment.’ (BNC HWN)

- Getting it right – technically speaking (BNC HX4)

- Technically speaking, of course, she was off duty now and one of the night sisters had responsibility for the unit [...]. (BNC JYB)

- [T]echnically speaking I suppose it is burnt but well done [...] (BNC KBP)

- [Speaker A:] And they class it as the south. Bloody ridiculous. [Speaker B:] Well it is, technically speaking, south of a ...(BNC KDD)

Taking a generous view, four of these are part of a clause that arguably contains a metaphor: (10f) uses hold as part of the phrase hold liable, instantiating a metaphor like “believing something about someone is holding them” (cf. also hold s.o. responsible/accountable, hold in high esteem); (10h) uses the verb evolve metaphorically to refer to a non-evolutionary development and then uses the spatial expressions towards and opposite direction metaphorically to describe the quality of the development; (10r) uses provide as part of the phrase provide employment, which instantiates a metaphor like “causing someone to be in a state is transferring an object to them” (cf. also provide s.o. with an opportunity/insight/ power...); (10t) contains the spatial preposition off as part of the phrase off duty, which could be said to instantiate the metaphor “a situation is a location”. Note that all four expressions involve highly conventionalized metaphors, that would hardly be noticed as such by speakers.

There are 7 hits for the sentence adverbial metaphorically speaking in the BNC:

-

- A convicted mass murderer has, for the second time, bloodied the nose, metaphorically speaking, of Malcolm Rifkind, the Secretary of State for Scotland, by successfully pursuing a claim for damages. (BNC A3G)

- Yet, when I was seven years old, I should have thought him a very silly little boy indeed not to have understood about metaphorically speaking, even if he had never heard of it, and it does seem that what he possessed in the way of scientific approach he lacked in common sense. (BNC AC7)

- Good caddies have good temperaments. Just watch Ian Wright getting a lambasting from Seve Ballesteros and see if Ian ever answers back, or, indeed, reacts in any way other than to quietly stand and take it on the chin, metaphorically speaking of course. (BNC ASA)

- Family [are] a safe investment, but in love you can make a killing overnight. Metaphorically speaking, I hasten to add. (BNC BMR)

- Metaphorically speaking, the research front is a frozen moment in time [...]. (BNC HPN)

- Gregory put the boot in... metaphorically speaking! (BNC K25)

- Mr Allenby are you ready to burst into song? Metaphorically speaking. (BNC KM7)

In clear contrast to technically speaking, six of these seven hits occur in clauses that contain a metaphor: bloody the nose of sb in (11a) means ‘be successful in court against sb’, instantiating the metaphor \(\mathrm{legal \space fight \space is \space physical \space fight}\); take it on the chin in (11c) means ‘endure being criticized’, instantiating the metaphor \(\mathrm{argument \space is \space physical \space fight}\); make a killing in (11d) means ‘be financially successful’, instantiating the metaphor \(\mathrm{commercial \space activity \space is \space a \space hunt}\); a frozen moment in time in (11e) means ‘documentation of a particular state’, instantiating the metaphor \(\mathrm{time \space is \space a \space flowing \space body \space of \space water}\); put the boot in in (11f) means ‘treat sb cruelly’, instantiating the metaphor \(\mathrm{life \space (or \space sports) \space is \space physical \space fight}\); burst into song in (11g) means “take one’s turn speaking”, instantiating the metaphor \(\mathrm{speaking \space is \space singing}\). The only exception is (11b); this is a metalinguistic use, indicating that someone did not understand that an utterance was meant metaphorically, rather than marking an utterance as metaphorical.

There are 13 hits for figuratively speaking in the BNC:

-

- The darts, the lumps of poison and the raw materials from which it is extracted all provide a challenge for others with a taste (figuratively speaking) for excitement. (BNC AC9)

- Alternatively, you could select spiky, upright plants like agaves or yuccas to transport you across the world, figuratively speaking, to the great deserts of North America. (BNC ACX)

- Palladium, statue of the goddess Pallas (Minerva) at Troy on which the city’s safety was said to depend, hence, figuratively speaking, the Bar seen as a bulwark of society. (BNC B0Y)

- Figuratively speaking, who would not give their right arm to find such a love? (BNC B21)

- [I]t is surprising to me that this process was ever permitted on this site at all (being figuratively speaking within arms length of the dwellings). (BNC B2D)

- Figuratively speaking, we also make the law of value serve our aims. (BNC BMA)

- This schlocky international movie, photographed in eye-straining colour, cashing in (figuratively speaking) on the craze for James Bond pictures [...]. (BNC C9U)

- He said: ‘I’m not sure if the princess held a gun to Charles’s head, figuratively speaking, but it seems if she wanted something said.’ (BNC CBF)

- Let’s pick someone completely at random, now we’ve had Tracey figuratively speaking! (BNC F7U)

- ‘Figuratively speaking’, he declared, ‘in case of need, Soviet artillerymen can support the Cuban people with their rocket fire [...]’. (BNC G1R)

- [Customer talking to a clerk about a coat.] ‘You told me it it was guaranteed waterproof.’ ‘I didn’t! I’ve never seen you before in my life!’ [...] ‘Figuratively speaking, I meant. I bought it a few months ago and I was assured they were waterproof.’ (BNC HGY)

- [T]he superego [...] possesses the notable psychological property of being – figuratively speaking – partly soluble in alcohol! (BNC HTP)

- Joan Daniels has now been appointed Honorary Treasurer of the Medau Society and we wish her the best of luck in balancing the books – figuratively speaking! (BNC KAE)

Here, we would expect to find not just metaphors but also other kinds of nonliteral language – which we do in almost all cases. The one exception is (12i), where the context (even enlarged beyond what is shown here) does not contain anything that could be a metaphor (it might be a metalinguistic use, indicating that the person called Tracey has been speaking figuratively). All other cases are clearly figurative: a taste for excitement in (12a) means ‘an experience’, instantiating the metaphor \(\mathrm{experience \space is \space taste}\); transport sb. across the world in (12b) means ‘make sb think of a distant location’, instantiating the metaphor \(\mathrm{imaginary \space distance \space is \space physical \space distance}\), bulwark of society in (12c) means ‘defender of society’, instantiating the metaphor \(\mathrm{defense \space is \space a \space wall}\), give one’s right arm to do sth in (12d) means ‘want sth very much’, instantiating the metonymy \(\mathrm{body \space part \space for \space personal \space value}\); be within arm’s length in (12e) means ‘be in close proximity’, instantiating the metonymy \(\mathrm{arm’s \space length \space for \space short \space distance}; make sth serve one’s aims in (12f) means ‘put sth to use in achieving sth’, instantiating the metaphor \(\mathrm{to \space be \space used \space is \space to \space serve}\); cash in in (12g) means ‘be successful’, instantiating the metaphor \(\mathrm{life \space is \space commercial \space transaction}\); hold gun to sb’s head in (12h) means ‘coerce sb to act’, instantiating the metaphor \(\mathrm{power \space is \space physical \space force}\); (12j) is from a speech by the Soviet head of state Nikita Khrushchev in which he uses artillery to refer metonymically about nuclear missiles; you told me in (12k) means ‘your co-employee told me’, instantiating the metonymy \(\mathrm{employee \space for \space company}\); the superego is soluble in alcohol in (12l) means ‘self-control disappears when drunk ’, instantiating the metaphor \(\mathrm{character \space is \space a \space physical \space substance}\); balance the books in (12m) means ‘make sure debits and credits match’, instantiating the metaphor \(\mathrm{abstract \space entities \space are \space physical \space entities}\).

We can now compare the literal and metaphorical contexts in which the expressions technically speaking and metaphorically/figuraltively speaking occur. If the latter are a metaphoricity signal, they should occur significantly more frequently in metaphorical contexts than the former. \(Table \text { } 11.12\) shows the tabulated results from the discussion above, subsuming metaphors and metonymies under \(\mathrm{figurative}\). The expected difference between contexts is clearly there, and statistically highly significant (\(\chi^{2}\) = 21.66, df = 1, \(p\) < 0.001, \(\phi\) = 0.7182).

\(Table \text { } 11.12\): Literal and figurative utterances containing the sentence adverbials metaphorically/figuratively speaking and technically speaking (BNC)

Of course, the question remains, why some metaphors should be explicitly signaled while the majority is not. For example, we might suspect that metaphorical expressions are more likely to be explicitly signaled in contexts in which they might be interpreted literally. This may be the case for put the boot in in (11f), which occurs in a description of a rugby game where one could potentially misread it for a statement that someone was actually kicked. Alternatively (or additionally), a metaphor may be signaled explicitly if its specific phrasing is more likely to be used in literal contexts. This may be the case with hold a gun to sb’s head in (12f): there are ten hits for this phrase in the BNC, only one of which is metaphorical. Again, which of these hypotheses (if any of them) is correct would have to be studied more systematically.

This case study found a clear effect where the authors of the study it is based on did not. This demonstrates the need to formulate specific predictions concerning the behavior of specific linguistic items in such a way that they can be tested systematically and the results be evaluated statistically. The study also shows that the area of metaphoricity signals is worthy of further investigation.

11.2.3.3 Case study: Metaphor and ideology

Regardless of whether metaphor is a rhetorical device (as has traditionally been assumed) or a cognitive device (as seems to be the majority view today), it is clear that it can serve an ideological function, allowing authors suggest a particular perspective on a given topic. Thus, an analysis of the metaphors used in texts manifesting a particular ideology should allow us to uncover those perspectives.

For example, Charteris-Black (2005) investigates a corpus of “right-wing communication and media reporting” on immigration, containing speeches, political manifestos and articles from the conservative newspapers Daily Mail and Daily Telegraph. He finds, among other things, that the metaphor “immigration is a flood” is used heavily, arguing that this allows the right to portray immigration as a disaster that must be contained, citing examples like a flood of refugees, the tide of immigration, and the trickle of applicants has become a flood.

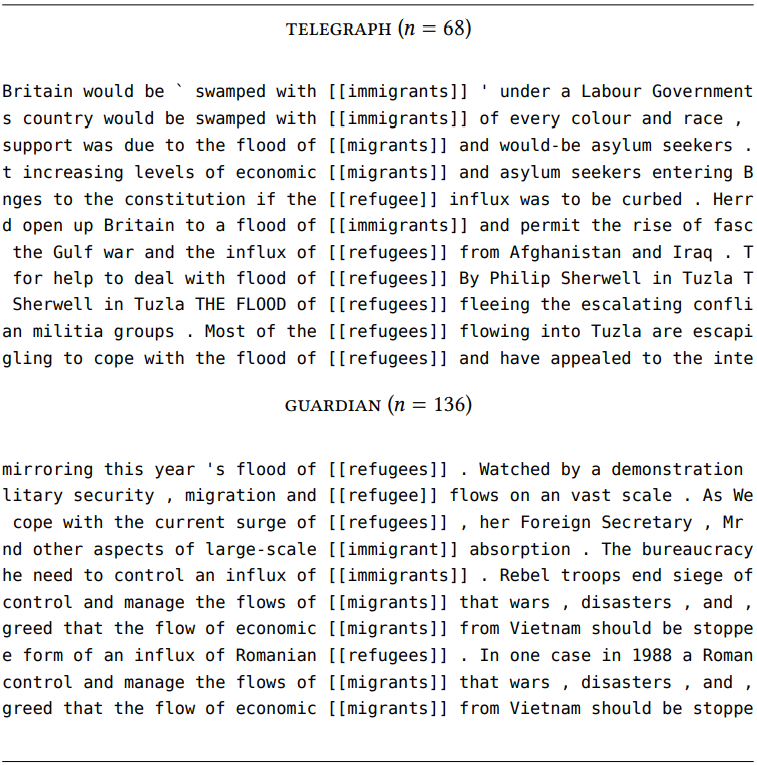

Charteris-Black’s findings are intriguing, but since he does not compare the findings from his corpus of right-wing materials to a neutral or a corresponding left-wing corpus, it remains an open question whether the use of these metaphors indicates a specifically right-wing perspective on immigration. Let us therefore replicate his analysis more systematically. The BNC contains 1 232 966 words from the Daily Telegraph (all files whose names begin with AH, AJ and AK), which will serve as our right-wing corpus, and 918 159 words from the Guardian (all files whose names begin with A8, A9 or AA, except file AAY), which will serve as our corresponding left-wing (or at least left-leaning) corpus. Since CharterisBlack’s examples all involve reference to target-domain items such as refugee and immigration, a metaphorical pattern analysis (cf. Section 11.2.2 above) suggests itself. \(Figure \text { } 11.5\) shows all concordance lines for the words migrant(s), immigrant(s) and refugee(s) containing metaphorical patterns instantiating the metaphor “immigration is a mass of water”.

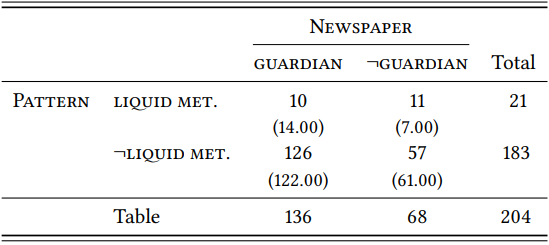

In terms of absolute frequencies, there is no great difference between the two subcorpora (10 vs. 11), but the overall number of hits for the words in question differs drastically: there are 136 instances of these words in the Guardian subcorpus but only half as many (68) in the Telegraph subcorpus. This means that relatively speaking, in the domain of migration liquid metaphor are more frequent than expected in the Telegraph and less frequent than expected in the Guardian (see \(Table \text{ } 11.13\)), which suggests that such metaphors are indeed typical of rightwing discourse. The difference just misses statistical significance, however, so a larger corpus would be required to corroborate the result (\(\chi^{2}\) = 3.822, df = 1, \(p\) = 0.0506, \(\phi\) = 0.1369).

This case study demonstrates that even general metaphors such as “immigration is a mass of water” may be associated with particular political ideologies. There is a large research literature on the role of metaphor in political discourse (see, for example, Koller 2004, Charteris-Black 2004, cf. also Musolff 2012), although at least part of this literature is not as systematic and quantitative as it

\(Figure \text { } 11.5\): Selected \(\mathrm{Liquid}\) metaphors with migrants(s), immigrants(s), refugee(s)

should be, so this remains a promising area of research). The case study also demonstrates the need to include a control sample in corpus-linguistic designs (in case that this still needed to be demonstrated at this point).

\(Table \text { } 11.13\): Liquid patterns with the words migrant(s), immigrant(s), refugee(s)

11.2.4 Metonymy

11.2.4.1 Case study: Subjects of the verb bomb

This chapter was concerned with metaphor, but touched upon metonymy in Case Study 11.2.3.2. While metaphor and metonymy are different phenomena, they are related by virtue of the fact that both of them are cases of non-literal language, and they tend to be of interest to the same groups of researchers, so let us finish the chapter with a short case study of metonymy, if only to see to what extent the methods introduced above can be transferred to this phenomenon.

Following Lakoff & Johnson (1980: 35), metonymy is defined in a broad sense here as “using one entity to refer to another that is related to it” (this includes what is often called synecdoche, see Seto (1999) for critical discussion). Text book examples are the following from Lakoff & Johnson (1980: 35, 39):

-

- The ham sandwich is waiting for his check

- Nixon bombed Hanoi.

In (13a), the metonym ham sandwich stands for the target expression ‘the person who ordered the ham sandwich’, in (13b) the metonym Nixon stands for the target expression ‘the air-force pilots controlled by Nixon’ (at least at first glance).

Thus, metonymy differs from metaphor in that it does not mix vocabulary from two domains, which has consequences for a transfer of the methods introduced for the study of metaphor in Section 11.1.

The source-domain oriented approach can be transferred relatively straightforwardly – we can query an item (or set of items) that we suspect may be used as metonyms then identify the actual metonymic uses. The main difficulty with this approach is choosing promising items for investigation. For example, the word sandwich occurs almost 900 times in the BNC, but unless I have overlooked one, it is not used as a metonym even once.

A straightforward analogue to the target-domain oriented approach (i.e., metaphorical pattern analysis) is more difficult to devise, as metonymies do not combine vocabulary from different semantic domains. One possibility would be to search for verbs that we know or suspect to be used with metonymic subjects and/or objects. For example, a Google search for \(\langle \text{"is waiting for (his|her| their|the) check"} \rangle\) turns up about 20 unique hits; most of these have people as subjects and none of them have meals as subjects, but there are three cases that have table as subject, as in (14):

- Table 12 is waiting for their check. (articles.baltimoresun.com)

Let us focus on the source-domain oriented perspective here, and let us use the famous example sentence in (13) as a starting point, loosely replicating the study in Stefanowitsch (2015). According to Lakoff and Johnson, this sentence instantiates what they call the “controller for controlled” metonymy, i.e. Nixon would be a metonym for the air force pilots controlled by Nixon.1 Thus, searching a corpus for sequences of a noun followed by the verb bomb should allow us to asses, for example, the importance of this metonymy in relation to other metonymies and literal uses.

Querying the BNC for \(\langle \text{[pos=".*NN.*"] [lemma="bomb" & pos=".*VB.*"]} \rangle\) yields 31 hits referring to the dropping of bombs. Of these, only a single one has the ultimate decision maker as a subject (cf. 15a). Somewhat more frequent in subject position are countries or inhabitants of countries (5 cases) (cf. 15b, c). Even more frequently, the organization responsible for carrying out the bombing – e.g. an air force, or part of an air force – is chosen as the subject (9 cases) (cf. 15d, e). The most frequent case (14 hits) mentions the aircraft carrying the bombs in subject position, often accompanied by an adjective referring to the country whose military operates the planes (cf 15f) or some other responsible group (cf. 15g). Finally, there are two cases where the bombs themselves occupy the subject position (cf. 15h).

-

- Mussolini bombed and gassed the Abyssinians into subjection.

- On the day on which Iraq bombed Larak...

- Seven years after the Americans bombed Libya...

- [T]he school was blasted by an explosion, louder than anything heard there since the Luftwaffe bombed it in 1944.

- ...Germany, whose Condor Legion bombed the working classes in Guernica...

- ... on Jan. 24 French aircraft bombed Iraq for the first time ...

- ... Rebel jets bombed the Miraflores presidential palace ...

- ... Watching our bombs bomb your people ...

Cases with pronouns in subject position – resulting from the query \(\langle \text{[pos=".* PNP.*"] [lemma="bomb" & pos=".*VB.*"]} \rangle\) – have a similar distribution, again, there is only one hit with a human controller in subject position. All hits (whether with pronouns, common nouns or proper names), interestingly, have metonymic subjects – i.e., not a single example has the bomber pilot in the subject position. This is unexpected, since literal uses should be more frequent than figurative uses (it leads Stefanowitsch (2015) to reject an analysis of such sentences as metonymies altogether). On the other hand, there are cases that are plausibly analyzed as metonymies here, such as examples (15d–e), which seem to instantiate a metonymy like \(\mathrm{military \space unit \space for \space member \space of \space unit}\) (i.e. \(\mathrm{whole \space for \space part}\)) and (15f–h), which instantiate \(\mathrm{plane \space for \space pilot}\) (i.e. \(\mathrm{instrument \space for \space controller}\)).

More systematic study of such metonymies by target domain could uncover more such facts as well as contributing to a general picture of how important particular metonymies are in a particular language.

This case study sketches a potential target-oriented approach to the corpusbased study of metonymy, along with some general questions that we might investigate using it (most obviously, the question of how central a given metonymy is in the language under investigation). Again, metonymy is a vastly under-researched area in corpus linguistics, so much work remains to be done.

1Alternatively, as argued by Stallard (1993), it is the predicate rather than the subject that is used metonymically in this sentence, which would make this a metonym-oriented case study.