1.1: What is Biopsychology?

- Page ID

- 110184

This page is a draft and under active development. Please forward any questions, comments, and/or feedback to the ASCCC OERI (oeri@asccc.org).

- Describe the field of biopsychology, its areas of focus, and other names for the field.

- Discuss a common myth about the brain and why it is false.

- Describe several brain imaging methods.

- Discuss materialism (physicalism) and determinism as assumptions underlying biopsychology.

- Describe the principle of brain organization referred to as "the localization of function."

Overview

Biopsychology is the study of biological mechanisms of behavior and mental processes. It examines the role of the nervous system, particularly the brain, in explaining behavior and the mind. This section defines biopsychology, critically examines a common myth about the brain, and briefly surveys some of the primary areas of research interest in biopsychology.

Biopsychology - The Interaction of Biology and Psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of behavior and mental processes in animals and humans. Modern psychology attempts to explain behavior and the mind from a wide range of perspectives. One branch of this discipline is biopsychology which is specifically interested in the biological causes of behavior and mental processes. Biopsychology is also referred to as biological psychology, behavioral neuroscience, physiological psychology, neuropsychology, and psychobiology. The focus of biopsychology is on the application of the principles of biology to the study of physiological, genetic, evolutionary, and developmental mechanisms of behavior in humans and other animals. It is a branch of psychology that concentrates on the role of biological factors, such as the central and peripheral nervous systems, neurotransmitters, hormones, genes, and evolution on behavior and mental processes.

Biological psychologists are interested in measuring biological, physiological, or genetic variables in an attempt to relate them to psychological or behavioral variables. Because all behavior is controlled by the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), biopsychologists seek to understand how the brain functions in order to understand behavior and mental activities. Key areas of focus within the field include sensation and perception; motivated behavior (such as hunger, thirst, and sex); control of movement; learning and memory; sleep and biological rhythms; and emotion. With advances in research methods, more complex topics such as language, reasoning, decision making, intelligence, and consciousness are now being studied intensely by biological psychologists.

Do humans use only 10% of their brains?

The frequently repeated claim that humans use only 10% of their brains is false. The exact origin of this myth is unknown, but misinterpretations of brain research are likely to blame. In experiments with animal brains during the 1800's through the early 1900's, Marie-Jean-Pierre Flourens and Karl Lashley destroyed and/or removed as much as 90% of the brain tissue of their animal subjects. Nevertheless, these animals could still perform basic behavioral and physiological functions. Some who read these results made the incorrect assumption that this meant that animals were using only 10% of their brains. Subsequently, this interpretation was generalized to humans (Elias and Saucer, 2006). Furthermore, prominent psychologists and researchers, such as Albert Einstein, Margaret Mead, and William James, were also quoted as saying that humans are using only a small portion of their brain (Elias and Saucer, 2006), fueling the 10% myth.

Due to advances in biopsychology and other related fields, we now have a greater understanding of the complexity of the brain. We may not be using our brains as efficiently as possible at all times, but we are using the entirety of our brain as each part contributes to our daily functioning. Studies of humans with brain damage have revealed that the effects of brain damage are correlated with where the damage is and how extensive it is. In other words, where damage occurs determines what functions are impacted and more damage has more of an effect. This reflects a key organizational principle of the brain: the localization of function. This principle means that specific psychological and behavioral processes are localized to specific regions and networks of the brain. For example, we now know that damage to an area of the brain known as the primary visual cortex, at the very back of your head in the occipital lobe, will result in blindness even though the rest of your visual system, including your eyes, is functioning normally. This syndrome is known as cortical blindness, to distinguish it from blindness that is caused by damage to the eyes. We now know that damage to a small area less than the size of a quarter at the very base of your brain results in disruption of feeding and regulation of body weight. Damage to another area of the brain located near your temples disrupts your ability to form new memories for facts and events, while leaving your ability to learn new motor tasks (such as skating or riding a bike) completely unaffected. Damage to another brain area causes face blindness, or prosopagnosia, a disorder in which the afflicted individual can still see normally except that they cannot recognize familiar faces, even the faces of close family members or even their own face in a photograph.

In the pages that follow in this textbook, you will learn many amazing things about the brain, and the nervous system in general. Get ready for many surprises as we explore the 3 pounds of brain tissue between our ears that make up the most complex piece of matter in the known universe. In this book, we examine some of what scientists now know about this astonishing organ, the brain, and how it functions to produce mind and behavior.

The Brain

The most important organ controlling our behavior and mental processes is the brain. Therefore, biopsychologists are especially interested in studying the brain, its neurochemical makeup, and how it produces behavior and mental processes (Wickens, 2021).

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Photo of the left side of a human brain. Front is at the left. The massive cerebral cortex hides many subcortical brain structures beneath. Note the folds on the surface of the cerebral cortex. This folding increases in mammal species with increasing complexity of the brain of the species and is thought to originate from the "cramming" of more cortical tissue into the skull over evolutionary time. (Image from Wikimedia Commons; File:Human brain NIH.png; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/F..._brain_NIH.png; image is from NIH and is in the public domain.).

Modern technology through neuroimaging techniques has given us the ability to look at living human brain structure and functioning in real time. Neuroimaging tools, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans, are often used to observe which areas of the brain are active during particular tasks in order to help psychologists understand the link between brain and behavior.

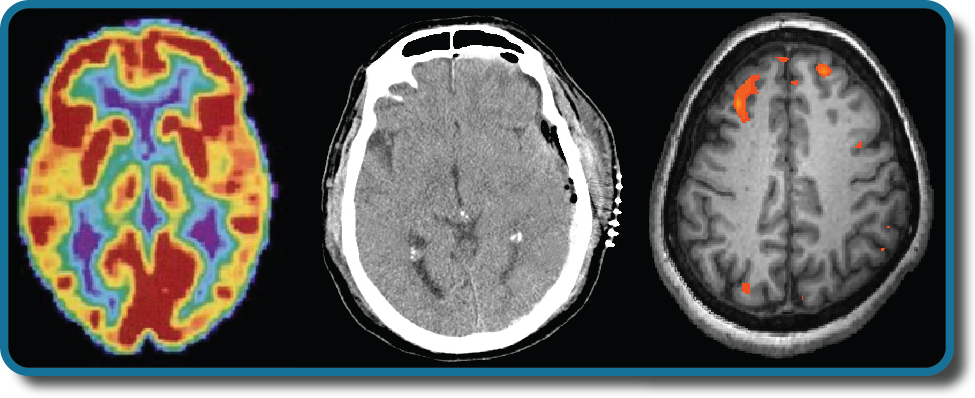

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Brain Imaging Techniques (Copyright; author via source)

Different brain-imaging techniques provide scientists with insight into different aspects of how the human brain functions. Three types of scans include (left to right) PET scan (positron emission tomography), CT scan (computed tomography), and fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging). (credit “left”: modification of work by Health and Human Services Department, National Institutes of Health; credit “center": modification of work by "Aceofhearts1968"/Wikimedia Commons; credit “right”: modification of work by Kim J, Matthews NL, Park S.)

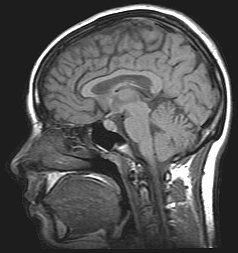

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the head are often used to help psychologists understand the links between brain and behavior. As will be discussed later in more detail, different tools provide different types of information. A functional MRI, for example, provides information regarding brain activity while an MRI provides only information about structure.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): MRI of Human Brain (public domain; via Wikimedia Commons)

A Scientific Model of the Universe: Two Basic Assumptions

The modern scientific view of the world assumes that there are at least two fundamental properties of the universe. The first assumption common to most scientists is that the entire universe is material or physical, composed exclusively of matter (including so-called dark matter) and energy (including electromagnetic energies such as light, heat, ultraviolet, and various other radiant energies, as well as other physical energies and forces such as electrical, gravitational, nuclear, and so forth). The entire universe is governed by physical laws. This view of the universe is called materialism or physicalism--the view that everything that exists in the universe consists of matter, energy, and other physical forces and processes.

Most important to biopsychology is the application of this principle to psychology and psychological processes. If everything in the universe is physical, then applied to psychology, including biopsychology, this means that the mind, our mental processes and subjective mental experiences, must also be entirely physical processes in an entirely material brain. Using this fundamental assumption of the modern scientific view of the universe, this means that the mind is entirely material, dependent upon the physical activities of an entirely material organ, the brain. On this view, the mind is what the brain does, and the brain and its processes are completely physical, material, just matter and energy in highly specific and organized form. This does not mean that all matter is conscious, nor does it mean that the mind is just energy. The key idea is that the matter and energy must be organized in a particular way. That is, a mind, consciousness, can only emerge from matter, energy, and physical processes if they are organized in a very specific and complex form--that form that we know as a brain and its physical operations. Where did brains come from and how did they acquire the specific organization of matter and energy needed to make a conscious mind within them? The scientific answer is evolution.

Although this is the view among most biological psychologists, there are a few who believe, like many students do, that the brain, along with the rest of life, was created by a divine being and that therefore the mind has divine origins. Typically, this belief is accompanied by the assumption that the mind is not physical, but that it is akin to the soul and the soul is believed to be non-material. Belief that the mind is non-material and therefore independent of the physical brain and its physical processes is known as mind-body dualism or mind-brain dualism, which literally means that the mind and the functioning of the brain (assumed to be entirely physical) are two (dual) separate processes, completely independent of one another. The origin of dualism is often attributed to the 17th century French philosopher and mathematician, Rene Descartes. If this view were true, then we would expect that brain damage would have no effect on the mind. However, brain damage does affect the mind and the specific location of the damage produces more or less specific, fairly predictable, effects on the mind, modifying the mind and behavior in various ways. Examples of this are coma due to head injury; the effects of Parkinson's disease on movement after the disease damages areas of the brain known as the basal ganglia; changes in personality and emotion due to injury to the front of the brain, specifically the frontal lobes; memory loss in Alzheimer's Disease; and so on. Though you don't have to accept the assumption of physicalism when studying the brain if your religious beliefs are contrary to the idea, nevertheless it is important that you be aware of the assumption of physicalism/materialism that most biological psychologists accept, at least as a working hypothesis, if not a philosophical position, as they do their brain research.

The second major assumption among most scientists is determinism--the belief that all events in the universe have prior causes and that these causes are external to the human will. This implies that humans do not have free will. Instead human behavior is caused by events external to us such as our upbringing, our social and cultural environment, by our brain structure and functioning, and by our genes and our evolution as a species. In some versions of this viewpoint, since we do not have control over many of the factors in our environment, our genes, and our evolution as a species, our brain function and thus our behavior is actually controlled by causes outside of our control. On this view, free will is an illusion that arises from our awareness of our mental processes as we make choices based on our selection of various behavioral options that we see open to us, but what we often fail to realize is that those choices are determined by many factors beyond our awareness and control (Koenigshofer, 2010, 2016). Free will vs. determinism is an issue that is far from being resolved and remains controversial even among scientists, including biological psychologists. Investigation by biological psychologists of the brain processes involved in choice and decision-making is ongoing and may eventually shed light on this difficult issue. Again, it is not necessary for you to be a determinist to study the brain, but it is important for you to be aware of the doctrine of determinism as you consider the implications of brain research as you progress through this textbook and your course in biological psychology.

References

Elias, Lorin J. and Saucier, Deborah M. (2006). Neuropsychology: Clinical and Experimental Foundations. Pearson.

Fredrickson, B. L., Maynard, K. E., Helms, M. J., Haney, T. L., Siegler, I. C., & Barefoot, J. C. (2000). Hostility predicts magnitude and duration of blood pressure response to angand Referenceser. Journal of behavioral medicine, 23(3), 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1005596208324

Koenigshofer, K. (2010). Mind Design: The Adaptive Organization of Human Nature, Minds, and Behavior. Pearson Educational Solutions, Boston.

Koenigshofer, K. (2016). Mind Design: The Adaptive Organization of Human Nature, Minds, and Behavior. Revised Edition. Amazon e-book.

Wickens, Andrew P. (2021). Introduction to Biopsychology. Sage Publishing.

Attributions

Adapted from Introduction to Psychology by Jennifer Walinga is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License