18.4: Chapter 3- Modern Primates and Their Evolution

- Page ID

- 110604

This page is a draft and under active development. Please forward any questions, comments, and/or feedback to the ASCCC OERI (oeri@asccc.org).

- Describe the distinguishing features of mammals and of primates

- Discuss the range of physical and behavioral traits in several different species of primate

- Describe general principles of brain evolution as proposed by Striedter (2006) and discuss one short coming of his principles

- List major steps in primate evolution

- Describe the taxonomic classification of our species, Homo sapiens

Overview

Humans are primates. We belong to the taxonomic order Primates. This order encompasses humans as well as non-human primates. Non-human primates are our closest biological and evolutionary relatives. So, we study them in order to learn more about ourselves. All primates are mammals.

General Mammalian Characteristics

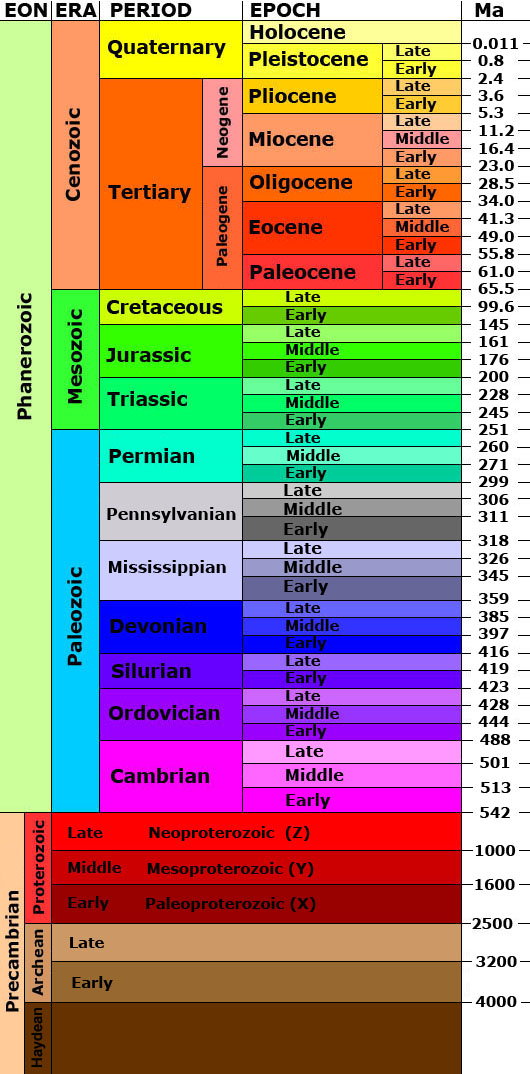

The earliest evidence of mammals is from the Mesozoic era (see table of geological time below), however, there is limited fossil evidence and the fossils that have been found are mouse-like forms with quadrupedal locomotion. Primates evolved from an ancestral mammal during the Cenozoic era and share many characteristics with other mammals. The Cenozoic is the era of the adaptive radiation of mammals with thirty different mammalian orders evolving.

Some of the general characteristics of mammals includes:

- mammary glands: females produce milk to feed young during their immediate post-natal growth period

- mammals have hair (sometimes called fur) that covers all or parts of their body

- the lower jaw is a single bone

- the middle ear contains three bones: stapes (stirrup), incus (anvil), and malleus (hammer)

- four-chambered heart

- main artery leaving the heart curves to the left to form the aortic arch

- mammals have a diaphragm

- mammals regulate their body temperature to maintain homeostais (a constant body temperature)

- teeth are replaced only once during lifetime

Primate Evolution in Summary

The first fifty million years of primate evolution was a series of adaptive radiations (diversification of a group of organisms into forms filling different ecological niches) leading to the diversification of the earliest lemurs, monkeys, and apes. The primate story begins in the forest canopy (overlapping branches and leaves high above ground) and understory of conifer-dominated forests, with our small, furtive ancestors subsisting at night, beneath the notice of day-active dinosaurs. From the archaic primates to the earliest groups of true primates (euprimates), the origin of our own order (the Primates) is characterized by the struggle for new food sources and microhabitats in the arboreal setting. Climate change forced major extinctions as the northern continents became increasingly dry, cold, and seasonal and as tropical rainforests gave way to deciduous forests, woodlands, and eventually grasslands. Lemurs, lorises, and tarsiers—once diverse groups containing many species—became rare, except for lemurs in Madagascar where there were no anthropoid competitors and perhaps few predators. Meanwhile, anthropoids (monkeys and apes) emerged in the Old World (Africa, Europe, and Asia), then dispersed across parts of the northern hemisphere, Africa, and ultimately South America. Meanwhile, the movement of continents, shifting sea levels, and changing patterns of rainfall and vegetation contributed to the developing landscape of primate biogeography, morphology, and behavior. Today’s primates provide a few reminders of the past diversity and remarkable adaptations of their extinct relatives.

A Simplified Classification of Living Primates

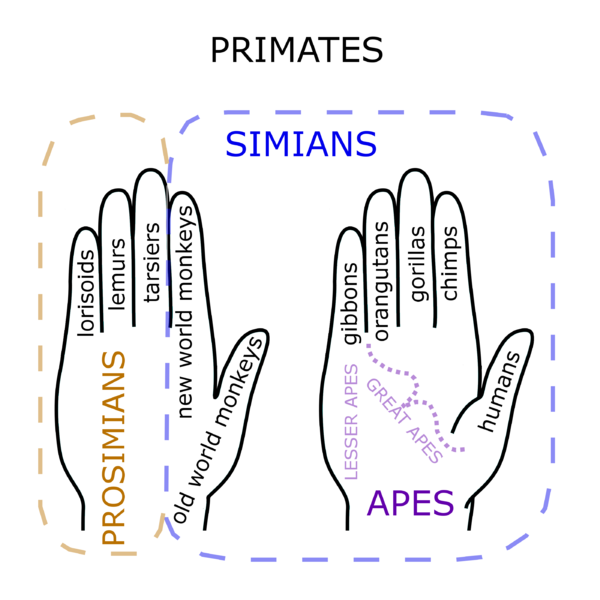

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): This image is a hand mnemonic used to help students learn a categorization of primates. The right hand (held palm upward) correlates to the apes, including the great apes and lesser apes. Humans are distinct from that group as the thumb is distinct from the other four digits of the hand. All apes evolved to be tailless, whereas species grouped onto the left hand are characterized as having tails (with certain exceptions, such as the Barbary macaque). Old world monkeys have a family name that means "tailed ape" and are indicated on the left thumb that points toward the right hand of apes. Old world monkeys are grouped with all of the apes in the parvorder called Catarrhini. New world monkeys on the left index finger form their own parvorder called Platyrrhini (meaning "flat nosed"). These are the only monkeys with prehensile tails. The group of simians (higher primates) are all apes and monkeys, so includes all of the above (Catarrhini and Platyrrhini). The three remaining digits on the left hand form the group of prosimians (lower primates).

The hand phalanges are not to be mistaken for a phylogeny as the branching geometry is not accurate. And the ten hand digits do not correspond to any single particular level of taxonomy. The specific correspondence of digits is:

- right thumb = genus Homo => 1 species: humans,

- right index = genus Pan => 2 species: common chimpanzees (4 subspecies) and bonobos,

- right middle = subfamily Gorillinae => genus Gorilla => 2 species: western gorillas (2 subspecies) and eastern gorillas (2 subspecies),

- right ring = subfamily Ponginae => genus Pongo => 2 species: Bornean orangutans (3 subspecies) and Sumatran orangutans,

- right pinky = family Hylobatidae => 4 genera of gibbons => nearly twenty species in total, including siamangs, lar gibbons and hoolock gibbons,

- left thumb = superfamily Cercopithecoidea (old world monkeys) => well over one hundred species including baboons and macaques,

- left index = parvorder Platyrrhini => superfamily Ceboidea (new world monkeys) => well over one hundred species including marmosets, tamarins, titis, howlers and squirrel monkeys,

- left middle = infraorder of tarsiers,

- left ring = superfamily of lemurs,

- left pinky = superfamily of lorisoids.

Categorization of humans has not been without controversy. One position is that homo sapiens are above apes and that it is improper to categorize the species as one of the great apes. The opposite extreme is the view that humans are "the third chimpanzee", based upon the very high percentage of genetic commonality between the species. This image follows a convention found between these two positions.

(Image and caption for Figure 18.4.2 from Wikimedia Commons; File:Primate Hand Mnemonic.png; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/F...d_Mnemonic.png; by Tdadamemd; licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license).

General Primate Characteristics

While primates share traits with other mammals, such as mammary glands and regulation of body temperature, there are a number of traits that all primates share. Because humans and non-human primates share a common evolutionary history (we have a common primate ancestor), human and non-human primates have a number of similar biological and behavioral traits.

Body

Hands

Primates have prehensile hands (and most of them have prehensile feet also). This means that they have the ability to grasp and manipulate objects. Primates have 5 digits on their hands and feet. Note that a few primates, like spider monkeys, have what are called vestigial thumbs. This means that they have either a very small or non-existent external thumb (but in that case, they will still have a small internal thumb bone).

Teeth

Primates have different teeth that perform different tasks when processing food via biting or chewing. Thus, they have the ability for a more generalized diet (compared to a specialist diet), meaning that they have more dietary flexibility. Why would this be a good thing to have?

Compare the teeth of the cayman (a relative of crocodiles and alligators) with the human teeth on the right. While the cayman's teeth do vary in size, they don't vary in structure. However, the human has incisors, canines, premolars, and molars -- all of which perform different food processing tasks.

_2006-09-19.jpg?revision=1)

Senses

Compared to most other mammals, primates have an increased reliance on vision and a decreased reliance on their senses of smell and hearing. Associated with this are their smaller, flattened noses, loss of whiskers, and relatively small, hairless ears. Also associated with this are their forward-facing eyes with accompanying binocular or stereoscopic vision. This type of vision means that both eyes have nearly the same field of vision with a lot of overlap between them. This arrangement provides good depth perception (but a loss of peripheral vision)--very useful for moving through tree branches.

Note first how the eyes of the monkey on the left are more front-facing than the eyes of the cow on the right. Also note how flat the monkey's nose is and how small its ears are, when compared to those of the cow.

Brain Evolution

Primate Life History

Primate Ecology

There are two primary environmental factors to consider: Food and Predators.

Food

Most primates are herbivores (they eat plant foods) and are dietary generalists. Some primates are omnivores and eat lots of things (plant and animal). However, some primates are more specialized.

Activity budgets

Why should we care about activity budgets?

Food and Feeding Competition

Spatial use: home ranges and territories

Primate Behavior

Primate Social Behavior

Social structure: the "whys" and the "hows"

Social strategies

In order to achieve their priorities, male and females must utilize certain social strategies.

Why be in a social group?

Types of primate social groups

Single-female multi-male

Primate Evolution

Fossils

Fossils are at the center of the study of ancestral primates. Animal fossils provide insight into morphology and behavior of ancient organisms while plant fossils help to determine what the landscape may have looked like during the time that a particular organism, including primates, lived there (remember, evolution is environmentally dependent!).

When a fossil is found, it can be dated using a variety of methods. Some methods date the fossil itself; other methods use the surrounding indicators There are relative dating techniques that provide an order of occurrence, but no absolute dates, and there are absolute, or chronometric, dating techniques that provide dates (usually a range of dates) for an object.

Geologic time

Tracking Primate Evolution

The Mesozoic: the origin of mammals

The Cenozoic era

The Paleocene epoch

Proto-primates, primate-like mammals, evolved in the Paleocene epoch, about 65 mya. The proto-primates from this epoch are controversial; some argue that they are related to primates but are not actually primates (hence, "proto-primates").

The Eocene epoch

The Oligocene epoch: the monkey/ape divergence (34 to 23 mya)

The Miocene epoch: the Old World monkey/ape divergence (23 to 5 mya)

Where did primates come from?

The Taxonomy of Humans

At this point, it is useful to review taxonomy, the biological classification of organisms, using the human species to illustrate the taxonomic classifications.

Figure \(\PageIndex{34}\): Taxonomic classification of humans illustrating taxonomic categories used for all living things. (Image from Wikimedia Commons; File:Biological classification of Humans Britfix.png; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/F...ns_Britfix.png; by L Pengo PD-User, Modified by Britfix; made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication).

Summary

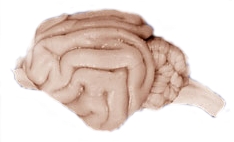

Humans are primates and primates are mammals. Both mammals and primates have distinguishing features, anatomical, physiological, and behavioral. One distinguishing feature of mammals with direct relevance for behavior is that only mammals have six-layered neocortex (cerebral cortex), while non-mammals lack six-layered cortex. Larger brains tend to be found in larger animals. Cerebral cortex developed as a result of natural selection, perhaps related to the increased information processing demands of living in complex social groups, although this is only one theory of the evolutionary origins of cerebral cortex. Brains are metabolically expensive organs--they require a lot of metabolic energy (in humans, the brain is only 2% of body weight, but it consumes 20% of the body's metabolic energy). Larger brains in human ancestors requiring more metabolic energy may have come about after ancestral humans began to eat meat, a concentrated source of calories and nutrients, and later to cook the meat making it easier to digest, leaving more metabolic energy from the meat to support energy requirements of bigger brains. In subsequent modules, we consider more details of hominin and human evolution.

References

Attributions

"Primate Evolution in Summary" adapted and modified by Kenneth A. Koenigshofer, Ph.D., Chaffey College, from Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology; https://explorations.americananthro.....php/chapters/; Chapter 8: Primate Evolution by Jonathan M. G. Perry, Ph.D. and Stephanie L. Canington, B.A.; Editors: Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera and Lara Braff, American Anthropological Association Arlington, VA 2019; CC BY-NC 4.0 International, except where otherwise noted.

Adapted and modified by Kenneth A. Koenigshofer, Ph.D., Chaffey College, from Biological Anthropology (Saneda and Field), chapters:

Modern Primates by Tori Saneda & Michelle Field via LibreTexts

Primate Ecology by Tori Saneda & Michelle Field via LibreTexts

Primate Evolution by Tori Saneda & Michelle Field via LibreTexts

"Brain Evolution" adapted by Kenneth A. Koenigshofer, Ph.D., Chaffey College, from Striedter (2006).

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=471&height=314)

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=384&height=405)