Section 2.3: Promoting Community-Driven Change in Family and Community Systems to Support Girls’ Holistic Development in Senegal

- Page ID

- 156482

The Big Picture

This is the story of the Girls’ Holistic Development Program designed and implemented by the non-profit organization, Grandmother Project – Change through Culture, in Southern Senegal starting in 2010 and evaluated on several occasions by outside researchers. The case study describes this innovative program, the results, and the lessons learned that are relevant to other African contexts, and to other collectivist cultures in the Global South or Global North. This author is the co-founder and Executive Director of the Grandmother Project initiative.

The Grandmother Project’s Mission

…is to improve the health and well-being of women, children, and families

in countries in the Global South, by empowering communities to drive their own development

by building on their own experience, resources, and cultural realities.

Senegal Community Context

Background of the Girls’ Holistic Development Program in Senegal

Preparatory Phase

Participatory and Rapid Qualitative Assessment

“We should go back to our roots. We need to recognize what is positive within our culture and hold on to it jealously.”

Demba, NGO community development worker

“If we lose our cultural values, we will be forced to replace them with other people’s values.”

Abdoulaye, Teacher

Series of Forum-Dialogues

Bassirou, Community Health Volunteer

“Even though we didn’t go to school, we understood everything, we shared our knowledge and everyone appreciated our ideas.”

Fatamata, Grandmother Leader

Traditionally in community meetings, there was no open communication between men and women. The inclusive nature of the forums, with men and women of different ages and statuses within the community, was appreciated by almost all community members. However, a few of the elders said that they felt uncomfortable being in the same meeting with people much younger than themselves.

“There is often a constraint in community discussions because different categories of community members do not openly speak up. It is good to bring together men and women of different social classes and ages so that everyone can learn from each other.”

Mballo, Former National Parliamentarian

“In other workshops, we grandmothers were criticized for our traditional ideas. That’s why, before coming, we were afraid. But we are happy that we could contribute to the discussion without being criticized.”

Oumou, Grandmother Leader

Partnership with the Ministry of Education (MOE)

Implementation of the Girls’ Holistic Development Program

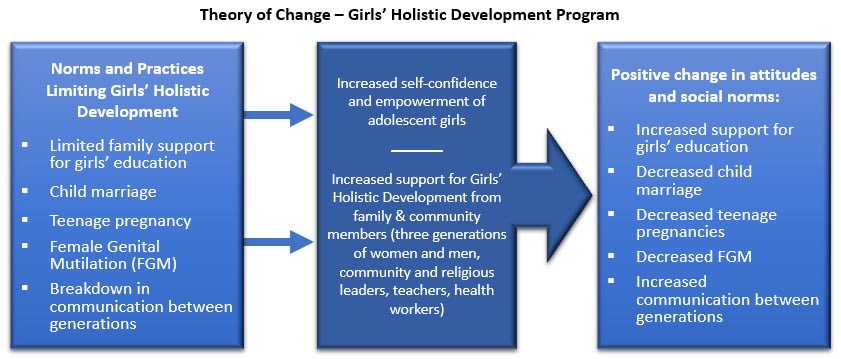

A Holistic Approach for Systemic Change

GHD Model

Program Goal and Objectives

Holistic Focus on Girls’ Rights and Needs

Building Communication Relationships

Involvement of Community Leaders

Building on Cultural and Religious Roles and Values

Program Components

Change through Culture Process of Change

Community Dialogue for Consensus-Building for Change

These key activities are briefly described below in terms of its purpose and participants.

“The intergenerational forums are very important as they help to re-establish dialogue between elders, parents, and youth. In the recent past, elders and adults didn’t listen to young people’s ideas and underestimated them. Thanks to the forums there is now more communication between older and younger community members.”

Grandmother Leader

“The forums have increased women’s confidence in themselves. Before, they didn’t dare express themselves in front of men. During community meetings, only men were allowed to speak. But now men know that women also have good ideas and encourage them to speak up.”

Young mother

“Before there was not enough discussion between men and women in families. It was a problem that separated them and was the root of frequent misunderstandings and arguments. The intergenerational forums have helped to solve this problem.”

Young adolescent boy

“We never before had the opportunity to sit all together and discuss like this although it is the best way to promote the development of our community elder leaders”

“This is a very important day because we are here to honor the grandmothers who are the teachers of young couples and of children. Before this project, the grandmothers were practically dead in the village and now they have been revived. It is since the grandmothers have resumed their role that teen pregnancies have greatly decreased.”

Mamadou, Village Elder

“Since we participated in the grandmother leadership training, the relationship between us grandmothers has changed. Now there is a permanent dialogue between us. Whenever one person has an idea of what we should do regarding our girls, we get together to discuss. Since the training, the relationships and communication between us have been strengthened”.

Grandmother Leader

“Thanks to these training sessions, I have become more confident. I no longer hesitate when there is something that needs to be said or done. I no longer bow my head when speaking before a group of men.

Grandmother Leader

“Before we used to scold our granddaughters all the time and they were rather afraid of us. Through the training, we realized that that is not a good way to communicate with them. Now we talk softly to the young girls and they listen to our advice with regards to sexuality and other things.”

Village headman’s wife

“These workshops support national priorities to increase children’s understanding and adoption of positive cultural values and to strengthen teacher-community relationships and communication”.

Amadou Lamine Wade, District Education Office Director

“Teachers alone do not have all of the knowledge that children need to learn. They also need to learn about positive cultural values and behavior. I don’t know of anyone else in the community who is more knowledgeable regarding the values that children should acquire. That is what justifies the presence of the grandmothers here today. And increased communication between teachers and grandmothers is very beneficial to children, especially to girls.”

Mr. Ba, Supervisor, District Education Office

“We are honored to have been invited to participate in this workshop along with teachers and school directors. We are going to work together with the teachers to encourage all children, those in school and not, to learn the values that are important in our culture.”

Maimouna, Grandmother

“There is a change in our relationships with our grandmothers. Before, we preferred to go to dancing parties or to watch television instead of being with them. Now, we spend more time with the grandmothers, listening to their stories that teach us about important values”.

Adolescent girl

”We are closer to our grandmothers now. If we have questions related to sexuality we can discuss them with our grandmothers, more easily than with our mothers. Now we are comfortable talking to the grandmothers”.

Adolescent girl

“This meeting has been very useful because it has allowed us to discuss important issues with others from our same village and with people from other villages. In our community we plan to organize meetings with all generations, to discuss what we can do together to prevent child marriage and FGM.”

Moussa, Village Headman

“These meetings are very beneficial because they encourage communication and understanding between us. During this meeting, I realized that FGM is not recommended by Islam. Many Imams were present and none of them support the practice”.

Cissé, Grandmother Leader