20.4: The Biology Of Memory

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 75135

Just as information is stored on digital media such as DVDs and flash drives, the information in LTM must be stored in the brain. The ability to maintain information in LTM involves a gradual strengthening of the connections among the neurons in the brain. When pathways in these neural networks are frequently and repeatedly fired, the synapses become more efficient in communicating with each other, and these changes create memory. This process, known as long-term potentiation (LTP), refers to the strengthening of the synaptic connections between neurons as result of frequent stimulation (Lynch, 2002). Drugs that block LTP reduce learning, whereas drugs that enhance LTP increase learning (Lynch et al., 1991). Because the new patterns of activation in the synapses take time to develop, LTP happens gradually. The period of time in which LTP occurs and in which memories are stored is known as the period of consolidation.

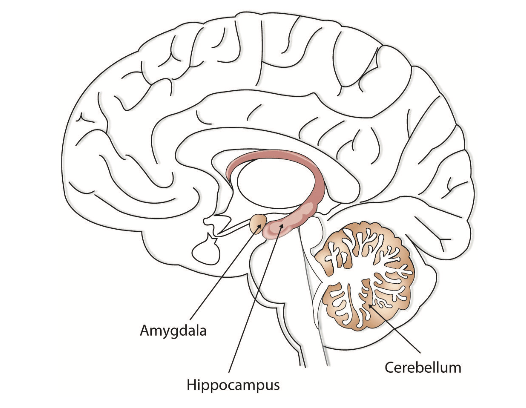

Memory is not confined to the cortex; it occurs through sophisticated interactions between new and old brain structures (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). One of the most important brain regions in explicit memory is the hippocampus, which serves as a preprocessor and elaborator of information (Squire, 1992). The hippocampus helps us encode information about spatial relationships, the context in which events were experienced, and the associations among memories (Eichenbaum, 1999). The hippocampus also serves in part as a switching point that holds the memory for a short time and then directs the information to other parts of the brain, such as the cortex, to actually do the rehearsing, elaboration, and long-term storage (Jonides et al., 2005). Without the hippocampus, which might be described as the brain’s “librarian,” our explicit memories would be inefficient and disorganized.

While the hippocampus is handling explicit memory, the cerebellum and the amygdala are concentrating on implicit and emotional memories, respectively. Research shows that the cerebellum is more active when we are learning associations and in priming tasks, and animals and humans with damage to the cerebellum have more difficulty in classical conditioning studies (Krupa et al., 1993; Woodruff-Pak et al., 2000). The storage of many of our most important emotional memories, and particularly those related to fear, is initiated and controlled by the amygdala (Sigurdsson et al., 2007).

Evidence for the role of different brain structures in different types of memories comes in part from case studies of patients who suffer from amnesia, a memory disorder that involves the inability to remember information. As with memory interference effects, amnesia can work in either a forward or a backward direction, affecting retrieval or encoding. For people who suffer damage to the brain, for instance, as a result of a stroke or other trauma, the amnesia may work backward. The outcome is retrograde amnesia, a memory disorder that produces an inability to retrieve events that occurred before a given time. Demonstrating the fact that LTP takes time (the process of consolidation), retrograde amnesia is usually more severe for memories that occurred just prior to the trauma than it is for older memories, and events that occurred just before the event that caused memory loss may never be recovered because they were never completely encoded.

Organisms with damage to the hippocampus develop a type of amnesia that works in a forward direction to affect encoding, known as anterograde amnesia. Anterograde amnesia is the inability to transfer information from short-term into long-term memory, making it impossible to form new memories. One well-known case study was a man named Henry Gustav Molaison (before he died in 2008, he was referred to only as H. M.) who had parts of his hippocampus removed to reduce severe seizures (Corkin et al., 1997). Following the operation, Molaison developed virtually complete anterograde amnesia. Although he could remember most of what had happened before the operation, and particularly what had occurred early in his life, he could no longer create new memories. Molaison was said to have read the same magazines over and over again without any awareness of having seen them before.

Cases of anterograde amnesia also provide information about the brain structures involved in different types of memory (Bayley & Squire, 2005; Helmuth, 1999; Paller, 2004). Although Molaison’s explicit memory was compromised because his hippocampus was damaged, his implicit memory was not (because his cerebellum was intact). He could learn to trace shapes in a mirror, a task that requires procedural memory, but he never had any explicit recollection of having performed this task or of the people who administered the test to him.

Although some brain structures are particularly important in memory, this does not mean that all memories are stored in one place. The American psychologist Karl Lashley (1929) attempted to determine where memories were stored in the brain by teaching rats how to run mazes, and then lesioning different brain structures to see if they were still able to complete the maze. This idea seemed straightforward, and Lashley expected to find that memory was stored in certain parts of the brain. But he discovered that no matter where he removed brain tissue, the rats retained at least some memory of the maze, leading him to conclude that memory isn’t located in a single place in the brain, but rather is distributed around it.

Long-term potentiation occurs as a result of changes in the synapses, which suggests that chemicals, particularly neurotransmitters and hormones, must be involved in memory. There is quite a bit of evidence that this is true. Glutamate, a neurotransmitter and a form of the amino acid glutamic acid, is perhaps the most important neurotransmitter in memory (McEntee & Crook, 1993). When animals, including people, are under stress, more glutamate is secreted, and this glutamate can help them remember (McGaugh, 2003). The neurotransmitter serotonin is also secreted when animals learn, and epinephrine may also increase memory, particularly for stressful events (Maki & Resnick, 2000; Sherwin, 1998). Estrogen, a female sex hormone, also seems critical, because women who are experiencing menopause, along with a reduction in estrogen, frequently report memory difficulties (Chester, 2001).

Our knowledge of the role of biology in memory suggests that it might be possible to use drugs to improve our memories, and Americans spend several hundred million dollars per year on memory supplements with the hope of doing just that. Yet controlled studies comparing memory enhancers, including Ritalin, methylphenidate, ginkgo biloba, and amphetamines, with placebo drugs find very little evidence for their effectiveness (Gold et al., 2002; McDaniel et al., 2002). Memory supplements are usually no more effective than drinking a sugared soft drink, which also releases glucose and thus improves memory slightly. This is not to say that we cannot someday create drugs that will significantly improve our memory. It is likely that this will occur in the future, but the implications of these advances are as yet unknown (Farah et al., 2004; Turner & Sahakian, 2006).

Although the most obvious potential use of drugs is to attempt to improve memory, drugs might also be used to help us forget. This might be desirable in some cases, such as for those suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) who are unable to forget disturbing memories. Although there are no existing therapies that involve using drugs to help people forget, it is possible that they will be available in the future. These possibilities will raise some important ethical issues: Is it ethical to erase memories, and if it is, is it desirable to do so? Perhaps the experience of emotional pain is a part of being a human being. And perhaps the experience of emotional pain may help us cope with the trauma.

REFERENCES

Baddeley, A., Eysenck, M. W., & Anderson, M. C. (2009). Memory. Psychology Press.

Bahrick, H. P. (1984). Semantic memory content in permastore: Fifty years of memory for Spanish learned in school. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113(1), 1–29. doi.org/10.1037/ 0096-3445.113.1.1

Bayley, P. J., & Squire, L. R. (2005). Failure to acquire new semantic knowledge in patients with large medial temporal lobe lesions. Hippocampus, 15(2), 273–280. doi.org/10.1002/hipo.20057

Bower, G. H. (1981). Mood and memory. American Psychologist, 36(2), 129–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.36.2.129

Bransford, J. D., & Johnson, M. K. (1972). Contextual prerequisites for understanding: Some investigations of comprehension and recall. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11(6), 717–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(72)80006-9

Chester, B. (2001). Restoring remembering: Hormones and memory. McGill Reporter, 33(10). https://web.archive.org/ web/20180810052901/https://www.mcgill.ca/reporter/33/10/sherwin/

Corkin, S., Amaral, D. G., González, R. G., Johnson, K. A., & Hyman, B. T. (1997). H. M.’s medial temporal lobe lesion: Findings from magnetic resonance imaging. The Journal of Neuroscience, 17(10), 3964–3979. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03964.1997

Craik, F. I., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11(6), 671–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(72)80001-X

Driskell, J. E., Willis, R. P., & Copper, C. (1992). Effect of overlearning on retention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(5), 615–622. doi. org/10.1037/0021-9010.77.5.615

Eich, E. (2008). Mood and memory at 26: Revisiting the idea of mood mediation in drug-dependent and place-dependent memory. In M. A. Gluck, J. R. Anderson, & S. M. Kosslyn (Eds.), Memory and mind: A festschrift for Gordon H. Bower (pp. 247–260). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eichenbaum, H. (1999). Conscious awareness, memory, and the hippocampus. Nature Neuroscience, 2(9), 775–776. doi. org/10.1038/12137

Farah, M. J., Illes, J., Cook-Deegan, R., Gardner, H., Kandel, E., King, P., Parens, E., Sahakian, B., & Wolpe, P. R. (2004). Neurocognitive enhancement: What can we do and what should we do? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 5(5), 421–425. https://doi.org/10.1038/ nrn1390

Godden, D. R., & Baddeley, A. D. (1975). Context-dependent memory in two natural environments: On land and underwater. British Journal of Psychology, 66(3), 325–331. doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1975. tb01468.x

Gold, P. E., Cahill, L., & Wenk, G. L. (2002). Ginkgo biloba: A cognitive enhancer? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 3(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/1529-1006.00006

Harris, J. L., & Qualls, C. D. (2000). The association of elaborative or maintenance rehearsal with age, reading comprehension and verbal working memory performance. Aphasiology, 14(5–6), 515–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/026870300401289

Helmuth, L. (1999). New role found for the hippocampus. Science, 285,

1339–1341. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.285.5432.1339b Jackson, A., Koek, W., & Colpaert, F. (1992). NMDA antagonists make

learning and recall state-dependent. Behavioural Pharmacology, 3(4), 415. doi.org/10.1097/00008877-199208000-00018

Jonides, J., Lacey, S. C., & Nee, D. E. (2005). Processes of working memory in mind and brain. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(1), 2–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00323.x

Krupa, D. J., Thompson, J. K., & Thompson, R. F. (1993). Localization of a memory trace in the mammalian brain. Science, 260(5110), 989–991. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.8493536

Lashley, K. S. (1929). The effects of cerebral lesions subsequent to the formation of the maze habit: Localization of the habit. In Brain mechanisms and intelligence: A quantitative study of injuries to the brain (pp. 86–108). University of Chicago Press.

Lynch, G. (2002). Memory enhancement: The search for mechanism- based drugs. Nature Neuroscience, 5(Suppl.), 1035–1038. doi. org/10.1038/nn935

Lynch, G., Larson, J., Staubli, U., Ambros-Ingerson, J., Granger, R., Lister, R. G., . . . Weingartner, H. J. (1991). Long-term potentiation and memory operations in cortical networks. In C. A. Wickliffe, M. Corballis, & G. White (Eds.), Perspectives on cognitive neuroscience (pp. 110–131). Oxford University Press.

Maki, P. M., & Resnick, S. M. (2000). Longitudinal effects of estrogen replacement therapy on PET cerebral blood flow and cognition. Neurobiology of Aging, 21(2), 373–383. doi.org/10.1016/ S0197-4580(00)00123-8

Marian, V. & Kaushanskaya, M. (2007). Language context guides memory content. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 14(5), 925–933. https:// doi.org/10.3758/BF03194123

McDaniel, M. A., Maier, S. F., & Einstein, G. O. (2002). “Brain-specific” nutrients: A memory cure? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 3(1), 12–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/1529-1006.00007

McEntee, W., & Crook, T. (1993). Glutamate: Its role in learning, memory, and the aging brain. Psychopharmacology, 111(4), 391–401. https:// doi.org/10.1007/BF02253527

McGaugh, J. L. (2003). Memory and emotion: The making of lasting memories. Columbia University Press.

Nickerson, R. S., & Adams, M. J. (1979). Long-term memory for a common object. Cognitive Psychology, 11(3), 287–307. doi.org/10.1016/ 0010-0285(79)90013-6

Paller, K. A. (2004). Electrical signals of memory and of the awareness of remembering. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(2), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00273.x

Rogers, T. B., Kuiper, N. A., & Kirker, W. S. (1977). Self-reference and the encoding of personal information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(9), 677–688. doi.org/10.1037/ 0022-3514.35.9.677

Rosch, E. (1975). Cognitive representations of semantic categories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 104(3), 192–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.104.3.192

Sherwin, B. B. (1998). Estrogen and cognitive functioning in women. Experimental Biology and Medicine, 217, 17–22. https://doi.org/ 10.3181/00379727-217-44200

Sigurdsson, T., Doyère, V., Cain, C. K., & LeDoux, J. E. (2007). Long-term potentiation in the amygdala: A cellular mechanism of fear learning and memory. Neuropharmacology, 52(1), 215–227. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.06.022

Squire, L. R. (1992). Memory and the hippocampus: A synthesis from findings with rats, monkeys, and humans. Psychological Review, 99(2), 195–231. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.99.2.195

Srull, T., & Wyer, R. (1989). Person memory and judgment. Psychological Review, 96(1), 58–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.1.58

Symons, C. S., & Johnson, B. T. (1997). The self-reference effect in memory: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 121(3), 371–394. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.371

Turner, D. C., & Sahakian, B. J. (2006). Analysis of the cognitive enhancing effects of modafinil in schizophrenia. In J. L. Cummings (Ed.), Progress in neurotherapeutics and neuropsychopharmacology (pp. 133–147). Cambridge University Press.

Woodruff-Pak, D. S., Goldenberg, G., Downey-Lamb, M. M., Boyko, O. B., & Lemieux, S. K. (2000). Cerebellar volume in humans related to magnitude of classical conditioning. NeuroReport, 11(3), 609–615. doi.org/10.1097/00001756-200002280-00035