22.4: Leaders And Leadership

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 75777

One type of person who has power over others, in the sense that they are able to influence them, is leaders. Leaders are in a position in which they can exert leadership, which is the ability to direct or inspire others to achieve goals (Chemers, 2001; Hogg, 2010). Leaders have many different influence techniques at their disposal. In some cases, they may give commands and enforce them with reward or coercive power, resulting in public conformity with the commands. In other cases, they may rely on well-reasoned technical arguments or inspirational appeals, making use of legitimate, referent, or expert power, with the goal of creating private acceptance and leading their followers to achieve.

Leadership is a classic example of the combined effects of the person and the social situation. Let’s consider first the person part of the equation and then turn to consider how the person and the social situation work together to create effective leadership.

Personality and Leadership

One approach to understanding leadership is to focus on person variables. Personality theories of leadership are explanations of leadership based on the idea that some people are simply “natural leaders” because they possess personality characteristics that make them effective (Zaccaro, 2007).

One personality variable that is associated with effective leadership is intelligence. Being intelligent improves leader- ship, as long as the leader is able to communicate in a way that is easily understood by his or her followers (Simonton, 1994, 1995). Other research has found that a leader’s social skills, such as the ability to accurately perceive the needs and goals of the group members, are also important to effective leadership. People who are more sociable, and therefore better able to communicate with others, tend to make good leaders (Kenny & Zaccaro, 1983; Sorrentino & Boutillier, 1975). Other variables that relate to leadership effectiveness include verbal skills, creativity, self-confidence, emotional stability, conscientiousness, and agreeableness (Cronshaw & Lord, 1987; Judge et al., 2002; Yukl, 2002). And of course the individual’s skills at the task at hand are important. Leaders who have expertise in the area of their leadership will be more effective than those who do not.

Because so many characteristics seem to be related to leader skills, some researchers have attempted to account for leadership not in terms of individual traits but in terms of a package of traits that successful leaders seem to have. Some have considered this in terms of charisma (Beyer, 1999; Conger & Kanungo, 1998). Charismatic leaders are leaders who are enthusiastic, committed, and self-confident; who tend to talk about the importance of group goals at a broad level; and who make personal sacrifices for the group. Charismatic leaders express views that support and validate existing group norms but that also contain a vision of what the group could or should be. Charismatic leaders use their referent power to motivate, uplift, and inspire others. And research has found a positive relationship between a leader’s charisma and effective leadership performance (Simonton, 1988).

Another trait-based approach to leadership is based on the idea that leaders take either transactional or transformational leadership styles with their subordinates (Avolio & Yammarino, 2003; Podsakoff et al., 1990). Transactional leaders are the more regular leaders who work with their subordinates to help them understand what is required of them and to get the job done. Transformational leaders, on the other hand, are more like charismatic leaders—they have a vision of where the group is going and attempt to stimulate and inspire their workers to move beyond their present status and to create a new and better future. Transformational leaders are those who can reconfigure or transform the group’s norms (Reicher & Hopkins, 2003).

the Person and the Situation

Despite the fact that there appear to be at least some personality traits that relate to leadership ability, the most important approaches to understanding leadership take into consideration both the personality characteristics of the leader and the situation in which the leader is operating. In some cases, the situation itself is important. For instance, you might remember that President George W. Bush’s ratings as a leader increased dramatically after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. This is a classic example of how a situation can influence the perceptions of a leader’s skill. In other cases, however, both the situation and the per- son are critical.

One well-known person-situation approach to under- standing leadership effectiveness was developed by Fred Fiedler and his colleagues (Ayman et al., 1995). The contingency model of leadership effectiveness is a model of leadership effectiveness that focuses on both person variables and situational variables. Fiedler conceptualized the leadership style of the individual as a relatively stable personality variable and measured it by having people consider all the people they had ever worked with and describe the person that they least liked to work with (their least preferred coworker). Those who indicated that they only somewhat disliked their least preferred coworker are relationship-oriented types of people, who are motivated to have close personal relationships with others. However, those who indicated that they did not like this coworker very much were classified as task-oriented types, who are motivated primarily by getting the job done.

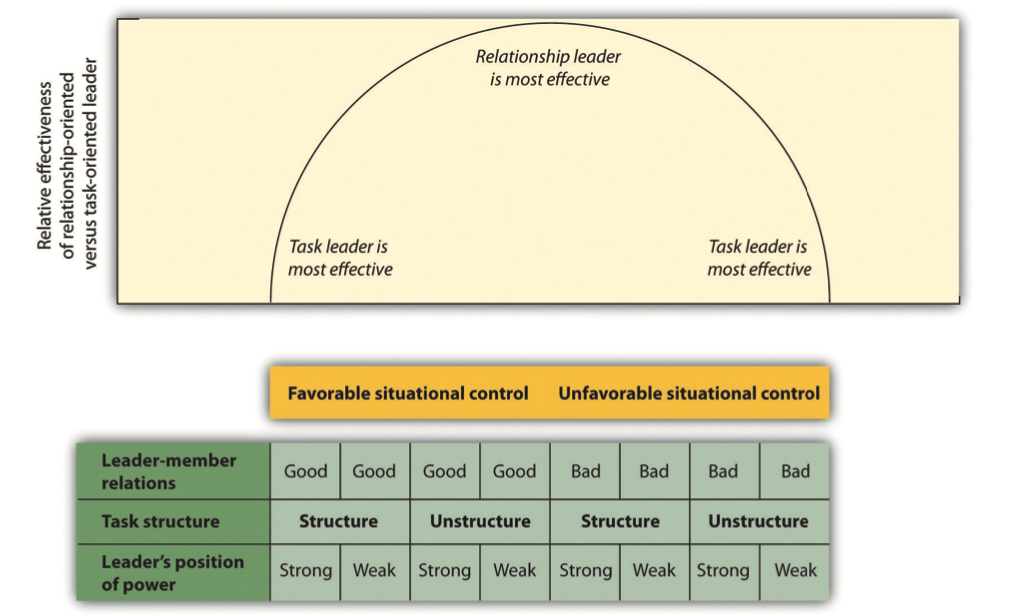

In addition to classifying individuals according to their leadership styles, Fiedler also classified the situations in which groups had to perform their tasks, both on the basis of the task itself and on the basis of the leader’s relationship to the group members. Specifically, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), Fiedler thought that three aspects of the group situation were important:

- The degree to which the leader already has a good relationship with the group and the support of the group members (leader-member relations)

- The extent to which the task is structured and unambiguous (task structure)

- The leader’s level of power or support in the organization (position power)

Furthermore, Fiedler believed that these factors were ordered in terms of their importance, such that leader-member relationships were more important than task structure, which was in turn more important than position power. As a result, he was able to create eight levels of the “situational favorableness” of the group situation, which roughly range from most favorable to least favorable for the leader. The most favorable relationship involves good relationships, a structured task, and strong power for the leader, whereas the least favorable relationship involves poor relationships, an unstructured task, and weak leader power.

The contingency model is interactionist because it pro- poses that individuals with different leadership styles will differ in effectiveness in different group situations. Task-oriented leaders are expected to be most effective in situations in which the group situation is very favorable because this gives the leader the ability to move the group forward, or in situations in which the group situation is very unfavorable and in which the extreme problems of the situation require the leader to engage in decisive action. However, in the situations of moderate favorableness, which occur when there is a lack of support for the leader or when the problem to be solved is very difficult or unclear, the more relationship-oriented leader is expected to be more effective. In short, the contingency model predicts that task-oriented leaders will be most effective either when the group climate is very favorable and thus there is no need to be concerned about the group members’ feelings, or when the group climate is very unfavorable and the task-oriented leader needs to take firm control.

Still another approach to understanding leadership is based on the extent to which a group member embodies the norms of the group. The idea is that people who accept group norms and behave in accordance with them are likely to be seen as particularly good group members and there- fore become leaders (Hogg, 2001; Hogg & van Knippenberg, 2003). Group members who follow group norms are seen as more trustworthy (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002) and are likely to engage in group-oriented behaviors to strengthen their leadership credentials (Platow & van Knippenberg, 2001).

REFERENCES

Anderson, C., & Berdahl, J. L. (2002). The experience of power: Examining the effects of power on approach and inhibition tendencies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1362–1377. doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1362

Anderson, C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2006). Power, optimism, and risk-taking. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36(4), 511–536. doi. org/10.1002/ejsp.324

Avolio, B. J., & Yammarino, F. J. (2003). Transformational and charismatic leadership: The road ahead. Elsevier Press.

Ayman, R., Chemers, M. M., & Fiedler, F. (1995). The contingency model of leadership effectiveness: Its level of analysis. Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 147–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(95)90032-2

Beyer, J. M. (1999). Taming and promoting charisma to change organizations. Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 307–330. doi. org/10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00019-3

Blass, T. (1999). The Milgram paradigm after 35 years: Some things we now know about obedience to authority. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(5), 955–978. doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999. tb00134.x

Borge, C. (2007, April 26). Basic instincts: The science of evil. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Primetime/sto...2765416&page=1

Chemers, M. M. (2001). Leadership effectiveness: An integrative review. In M. A. Hogg & R. S. Tindale (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Group processes (pp. 376–399). Blackwell.

Chen, S., Lee-Chai, A. Y., & Bargh, J. A. (2001). Relationship orientation as a moderator of the effects of social power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(2), 173–187. doi.org/10.1037/ 0022-3514.80.2.173

Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. N. (1998). Charismatic leadership in organizations. Sage.

Cronshaw, S. F., & Lord, R. G. (1987). Effects of categorization, attribution, and encoding processes on leadership perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 97–106. doi.org/10.1037/ 0021-9010.72.1.97

Dépret, E., & Fiske, S. T. (1999). Perceiving the powerful: Intriguing individuals versus threatening groups. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35(5), 461–480. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1999.1380

Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2002). Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 611–628. doi.org/10.1037/ 0021-9010.87.4.611

Driefus, C. (2007, April 3). Finding hope in knowing the universal capacity for evil. New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2007/04/03/ science/03conv.html

Fiske, S. T. (1993). Controlling other people: The impact of power on stereotyping. American Psychologist, 48(6), 621–628. doi. org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.6.621

French, J. R. P., & Raven, B. H. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in social power (pp. 150–167). Institute for Social Research.

Galinsky A. D., Gruenfeld, D. H, & Magee, J. C. (2003). From power to action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(3), 453–466. doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.453

Heath, T. B., McCarthy, M. S., and Mothersbaugh, D. L. (1994). Spokesperson fame and vividness effects in the context of issue- relevant thinking: The moderating role of competitive setting. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 520–534. doi.org/10.1086/ 209367

Henrich, J., & Gil-White, F. (2001). The evolution of prestige: Freely conferred status as a mechanism for enhancing the benefits of cultural transmission. Evolution and Human Behavior, 22(3), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-5138(00)00071-4

Hogg, M. A. (2001). A social identity theory of leadership. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(3), 184–200. doi.org/10.1207/ S15327957PSPR0503_1

Hogg, M. A. (2010). Influence and leadership. In S. F. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 1166– 1207). Wiley.

Hogg, M. A., & van Knippenberg, D. (2003). Social identity and leadership processes in groups. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 1–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(03)01001-3

Judge, T., Bono, J., Ilies, R., & Gerhardt, M. (2002). Personality and leadership: A qualitative and quantitative review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 765–780. doi.org/10.1037/ 0021-9010.87.4.765

Kamins, A. M. (1989). Celebrity and noncelebrity advertising in a two-sided context. Journal of Advertising Research, 29(3), 34–42.

Kelman, H. (1961). Processes of opinion change. Public Opinion Quarterly, 25, 57–78. doi.org/10.1086/266996

Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H., & Anderson, C. (2003). Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological Review, 110(2), 265–284. doi. org/10.1037/0033-295X.110.2.265

Kenny, D. A., & Zaccaro, S. J. (1983). An estimate of variance due to traits in leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68(4), 678–685. https:// doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.68.4.678

Kilham, W., & Mann, L. (1974). Level of destructive obedience as a function of transmitter and executant roles in the Milgram obedience paradigm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29(5), 692–702. doi.org/10.1037/h0036636

Kipnis, D. (1972). Does power corrupt? Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 24, 33–41. doi.org/10.1037/h0033390

Meeus, W. H., & Raaijmakers, Q. A. (1986). Administrative obedience:

Carrying out orders to use psychological-administrative violence. European Journal of Social Psychology, 16(4), 311–324. doi. org/10.1002/ejsp.2420160402

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view. Harper & Row.

Molm, L. D. (1997). Coercive power in social exchange. Cambridge University Press.

Platow, M. J., & van Knippenberg, D. (2001). A social identity analysis of leadership endorsement: The effects of leader in-group prototypicality and distributive intergroup fairness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(11), 1508–1519. doi. org/10.1177/01461672012711011

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Moorman, R. H., & Fetter, R. (1990). Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadership Quarterly, 1(2), 107–142. doi. org/10.1016/1048-9843(90)90009-7

Raven, B. H. (1992). A power/interaction model of interpersonal influence: French and Raven thirty years later. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 7(2), 217–244.

Reicher, S., & Haslam, S. A. (2006). Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC prison study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45(1), 1–40. doi.org/10.1348/014466605X48998

Reicher, S. D., & Hopkins, N. (2003). On the science of the art of leadership. In D. van Knippenberg and M. A. Hogg (Eds.), Leadership and power: Identity processes in groups and organizations

(pp. 197–209). Sage.

Simonton, D. K. (1988). Presidential style: Personality, biography and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(6), 928–936. doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.55.6.928

Simonton, D. K. (1994). Greatness: Who makes history and why. Guilford Press.

Simonton, D. K. (1995). Personality and intellectual predictors of leadership. In D. H. Saklofske & M. Zeidner (Eds.), International handbook of personality and intelligence (pp. 739–757). Plenum.

Sorrentino, R. M., & Boutillier, R. G. (1975). The effect of quantity and quality of verbal interaction on ratings of leadership ability. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 11(5), 403–411. doi. org/10.1016/0022-1031(75)90044-X

Tepper, B. J., Carr, J. C., Breaux, D. M., Geider, S., Hu, C., & Hua, W. (2009). Abusive supervision, intentions to quit, and employees’ workplace deviance: A power/dependence analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109(2), 156–167. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.03.004

van Kleef, G. A., Oveis, C., van der Löwe, I., LuoKogan, A., Goetz, J., & Keltner, D. (2008). Power, distress, and compassion: Turning a blind eye to the suffering of others. Psychological Science, 19(12), 1315–1322. doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02241.x

Wilson, E. J., &. Sherrell, D. L. (1993). Source effects in communication and persuasion: A meta-analysis of effect size. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 21(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/BF02894421

Yukl, G. A. (2002). Leadership in organizations. Prentice Hall.

Zaccaro, S. J. (2007). Trait-based perspectives of leadership. American Psychologist, 62(1), 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.1.6

Zimbardo, P. G. (n.d.). The story: An overview of the experiment. Stanford Prison Experiment. https://www.prisonexp.org/the-story