8.1: Introduction

- Page ID

- 123561

Charles Stangor, Jennifer Walinga, and Lee Sanders

Canada has had its share of memories being introduced into legal cases with devastating results: Thomas Sophonow was accused of murdering a young waitress who worked in a donut shop in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Several eyewitnesses testified against Sophonow but there were problems with each one. For example, the photo array shown to a number of witnesses contained a picture of Sophonow, which was significantly different than the other men in the array.

Dubious allegations of repressed memories forced Michael Kliman, a teacher at James McKinney Elementary School in Richmond, B.C., to endure three trials before his ultimate acquittal. His world came crashing down when he was accused of molesting a Grade 6 student some 20 years earlier, a student who “recovered” her memories 17 years after the abuse allegedly happened. According to an article in the Vancouver Sun (Brook, 1999): “In 1992, after years of psychiatric treatment, she ‘recovered’ long-lost memories of a year-long series of assaults by Kliman and, encouraged by the Richmond RCMP, laid charges.”

Warning: Discussions of violence and sexual assault in the following case study.

She Was Certain, but She Was Wrong

In 1984 Jennifer Thompson was a 22-year-old college student in North Carolina. One night a man broke into her apartment, put a knife to her throat, and raped her. According to her own account, Ms. Thompson studied her rapist throughout the incident with great determination to memorize his face. She said:

“I studied every single detail on the rapist’s face. I looked at his hairline; I looked for scars, for tattoos, for anything that would help me identify him. When and if I survived.”

Ms. Thompson went to the police that same day to create a sketch of her attacker, relying on what she believed was her detailed memory. Several days later, the police constructed a photographic lineup. Thompson identified Ronald Cotton as the rapist, and she later testified against him at trial. She was positive it was him, with no doubt in her mind.

“I was sure. I knew it. I had picked the right guy, and he was going to go to jail. If there was the possibility of a death sentence, I wanted him to die. I wanted to flip the switch.”

As positive as she was, it turned out that Jennifer Thompson was wrong. But it was not until after Mr. Cotton had served 11 years in prison for a crime he did not commit that conclusive DNA evidence indicated that Bobby Poole was the actual rapist, and Cotton was released from jail. Jennifer Thompson’s memory had failed her, resulting in a substantial injustice. It took definitive DNA testing to shake her confidence, but she now knows that despite her confidence in her identification, it was wrong. Consumed by guilt, Thompson sought out Cotton when he was released from prison, and they have since become friends (Innocence Project, n.d.; Thompson, 2000).

Although Jennifer Thompson was positive that it was Ronald Cotton who had raped her, her memory was inaccurate. Conclusive DNA testing later proved that he was not the attacker. Watch this book trailer about the story.

Video: Picking Cotton: A Memoir of Injustice and Redemption [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nLGXrviy5Iw]

Jennifer Thompson is not the only person to have been fooled by her memory of events. Over the past 10 years, almost 400 people have been released from prison when DNA evidence confirmed that they could not have committed the crime for which they had been convicted. And in more than three-quarters of these cases, the cause of the innocent people being falsely convicted was erroneous eyewitness testimony (Wells, Memon, & Penrod, 2006).

Watch this video for Lesley Stahl’s 60 Minutes segment on this case.

Video: Eyewitness Testimony [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=97DSyF_Z3Do]

The two subjects of this chapter are memory, defined as the ability to store and retrieve information over time, and cognition, defined as the processes of acquiring and using knowledge. It is useful to consider memory and cognition in the same chapter because they work together to help us interpret and understand our environments.

Memory and cognition represent the two major interests of cognitive psychologists. The cognitive approach became the most important school of psychology during the 1960s, and the field of psychology has remained in large part cognitive since that time. The cognitive school was greatly influenced by the development of the electronic computer, and although the differences between computers and the human mind are vast, cognitive psychologists have used the computer as a model for understanding the workings of the mind.

Differences between Brains and Computers

- In computers, information can be accessed only if one knows the exact location of the memory. In the brain, information can be accessed through spreading activation from closely related concepts.

- The brain operates primarily in parallel, meaning that it is multitasking on many different actions at the same time. Although this is changing as new computers are developed, most computers are primarily serial — they finish one task before they start another.

- In computers, short-term (random-access) memory is a subset of long-term (read-only) memory. In the brain, the processes of short-term memory and long-term memory are distinct.

- In the brain, there is no difference between hardware (the mechanical aspects of the computer) and software (the programs that run on the hardware).

- In the brain, synapses, which operate using an electrochemical process, are much slower but also vastly more complex and useful than the transistors used by computers.

- Computers differentiate memory (e.g., the hard drive) from processing (the central processing unit), but in brains there is no such distinction. In the brain (but not in computers) existing memory is used to interpret and store incoming information, and retrieving information from memory changes the memory itself.

- The brain is self-organizing and self-repairing, but computers are not. If a person suffers a stroke, neural plasticity will help him or her recover. If we drop our laptop and it breaks, it cannot fix itself.

- The brain is significantly bigger than any current computer. The brain is estimated to have 25,000,000,000,000,000 (25 million billion) interactions among axons, dendrites, neurons, and neurotransmitters, and that doesn’t include the approximately 1 trillion glial cells that may also be important for information processing and memory.

Although cognitive psychology began in earnest at about the same time that the electronic computer was first being developed, and although cognitive psychologists have frequently used the computer as a model for understanding how the brain operates, research in cognitive neuroscience has revealed many important differences between brains and computers. The neuroscientist Chris Chatham (2007) provided the list of differences between brains and computers shown here. You might want to check out the website and the responses to it at http://scienceblogs.com/developingintelligence/2007/03/27/why-the-brain-is-not-like-a-co/.

We will begin the chapter with the study of memory. Our memories allow us to do relatively simple things, such as remembering where we parked our car or the name of the current prime minister of Canada, but also allow us to form complex memories, such as how to ride a bicycle or to write a computer program. Moreover, our memories define us as individuals — they are our experiences, our relationships, our successes, and our failures. Without our memories, we would not have a life.

At least for some things, our memory is very good (Bahrick, 2000). Once we learn a face, we can recognize that face many years later. We know the lyrics of many songs by heart, and we can give definitions for tens of thousands of words. Mitchell (2006) contacted participants 17 years after they had been briefly exposed to some line drawings in a lab and found that they still could identify the images significantly better than participants who had never seen them.

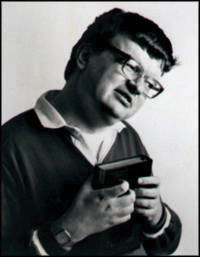

Figure 8.1 Kim Peek.

For some people, memory is truly amazing. Consider, for instance, the case of Kim Peek, who was the inspiration for the Academy Award-winning film Rain Man (Figure 8.1 “Kim Peek” and “Video Clip: Kim Peek”). Although Peek’s IQ was only 87, significantly below the average of about 100, it is estimated that he memorized more than 10,000 books in his lifetime (Wisconsin Medical Society, n.d.; Kim Peek, 2004). The Russian psychologist A. R. Luria (2004) has described the abilities of a man known as “S,” who seems to have unlimited memory. S remembers strings of hundreds of random letters for years at a time, and seems in fact to never forget anything.

You can view an interview with Kim Peek and see some of his amazing memory abilities at this link.

Video: Kim Peek [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dhcQG_KItZM]

In this chapter we will see how psychologists use behavioural responses (such as memory tests and reaction times) to draw inferences about what and how people remember. And we will see that although we have very good memories for some things, our memories are far from perfect (Schacter, 1996). The errors that we make are due to the fact that our memories are not simply recording devices that input, store, and retrieve the world around us. Rather, we actively process and interpret information as we remember and recollect it, and these cognitive processes influence what we remember and how we remember it. Because memories are constructed, not recorded, when we remember events we don’t reproduce exact replicas of those events (Bartlett, 1932).

We will also focus on cognition in the last section of the chapter, with consideration for cases in which cognitive processes lead us to distort our judgments or misremember information. We will see that our prior knowledge can influence our memory. People who read the words “dream, sheets, rest, snore, blanket, tired, and bed” and then are asked to remember the words often think that they saw the word sleep even though that word was not in the list (Roediger & McDermott, 1995). And we will see that in other cases we are influenced by the ease with which we can retrieve information from memory or by the information that we are exposed to after we first learn something.

Although much research in the area of memory and cognition is basic in orientation, the work also has profound influence on our everyday experiences. Our cognitive processes influence the accuracy and inaccuracy of our memories and our judgments, and they lead us to be vulnerable to the types of errors that eyewitnesses such as Jennifer Thompson may make. Understanding these potential errors is the first step in learning to avoid them. Laney & Loftus (2008) suggest that there are common types of errors made that can help explain human memory and its interactions with the legal system.

Misinformation can be introduced into the memory of a witness between the time of seeing an event and reporting it later. Something as straightforward as which sort of traffic sign was in place at an intersection can be confused if subjects are exposed to erroneous information after the initial incident. This is called the misinformation effect, because the misinformation that subjects are exposed to after the event can contaminates subjects’ memories of what they witnessed. Studies have demonstrated that memory can be contaminated by erroneous information that people are exposed to after they witness an event. The misinformation in these studies has led people to incorrectly remember everything from small but crucial details of a perpetrator’s appearance to objects as large as a barn that wasn’t there at all. False memory studies suggest that once these false memories are implanted it is difficult to tell them apart from true memories (Bernstein & Loftus, 2009; Laney & Loftus, 2008).

In addition to correctly remembering the many details of a crime, eyewitnesses often need to remember the faces and other identifying features of the perpetrators of those crimes. There is a substantial body of research demonstrating that eyewitnesses can make serious, but often understandable and even predictable, errors while engaging with mug shots, photo spreads, and line up. Memory is also susceptible to a wide variety of biases and errors. People can forget events that happened to them and people they once knew. They can mix up details across time and place. They can even remember whole complex events that never happened at all.

The problems with memory in the legal system are real. Recommendations to improve the use and reliance on eyewitness testimony have been made, and many of these are in the process of being implemented. Some are aimed at specific legal procedures, including when and how witnesses should be interviewed, and how lineups should be constructed and conducted. Other recommendations call for appropriate education (often in the form of expert witness testimony) to be provided to jury members and others tasked with assessing eyewitness memory. Eyewitness testimony can be of great value to the legal system, but decades of research now argues that this testimony is often given far more weight than its accuracy justifies.

Image Attributions

Figure 8.1: Kim Peek by Darold A. Treffert, MD, and the Wisconsin Medical Society (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Peek1.jpg) used under CC BY license.

References

Bahrick, H. P. (2000). Long-term maintenance of knowledge. In E. Tulving & F. I. M. Craik (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of memory (pp. 347–362). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Bernstein, D. M., & Loftus, E. F., (2009a). How to tell if a particular memory is true or false. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 370–374.

Brook, P. (1999, December 15). Accused falls victim to a legal nightmare. The Vancouver Sun, p. A19.

Chatham, C. (2007, March 27). 10 important differences between brains and computers. Developing Intelligence. Retrieved from http://scienceblogs.com/developingin...not-like-a-co/

Innocence Project. (n.d.). Ronald Cotton. Retrieved from http://www.innocenceproject.org/Content/72.php.

Kim Peek: Savant who was the inspiration for the film Rain Man. (2004, December 23). The Times. Retrieved from http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/com...cle6965115.ece

Laney, C., & Loftus, E. F. (2008). Emotional content of true and false memories. Memory, 16, 500–516.

Luria, A. (2004). The mind of a mnemonist: A little book about a vast memory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mitchell, D. B. (2006). Nonconscious priming after 17 years: Invulnerable implicit memory? Psychological Science, 17(11), 925–928.

Roediger, H. L., & McDermott, K. B. (1995). Creating false memories: Remembering words not presented in lists. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 21(4), 803–814.

Schacter, D. L. (1996). Searching for memory: The brain, the mind, and the past (1st ed.). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Thompson, J. (2000, June 18). I was certain, but I was wrong. New York Times. Retrieved from http://faculty.washington.edu/gloftu...6_18_2000.html

Wells, G. L., Memon, A., & Penrod, S. D. (2006). Eyewitness evidence: Improving its probative value. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 7(2), 45–75.

Wisconsin Medical Society. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.wisconsinmedicalsociety.o...ion/video.html.

Contributors and Attributions

- Introduction to Psychology by Jorden A. Cummings & Lee Sanders is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- Refer to Source Chapter Attributions for more details