3.3: Taste and Smell

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 90549

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

University of Florida

Humans are omnivores (able to survive on many different foods). The omnivore’s dilemma is to identify foods that are healthy and avoid poisons. Taste and smell cooperate to solve this dilemma. Stimuli for both taste and smell are chemicals. Smell results from a biological system that essentially permits the brain to store rough sketches of the chemical structures of odor stimuli in the environment. Thus, people in very different parts of the world can learn to like odors (paired with calories) or dislike odors (paired with nausea) that they encounter in their worlds. Taste information is preselected (by the nature of the receptors) to be relevant to nutrition. No learning is required; we are born loving sweet and hating bitter. Taste inhibits a variety of other systems in the brain. Taste damage releases that inhibition, thus intensifying sensations like those evoked by fats in foods. Ear infections and tonsillectomies both can damage taste. Adults who have experienced these conditions experience intensified sensations from fats and enhanced palatability of high-fat foods. This may explain why individuals who have had ear infections or tonsillectomies tend to gain weight.

learning objectives

- Explain the salient properties of taste and smell that help solve the omnivore’s dilemma.

- Distinguish between the way pleasure/displeasure is produced by smells and tastes.

- Explain how taste damage can have extensive unexpected consequences.

The Omnivore's Dilemma

Humans are omnivores. We can survive on a wide range of foods, unlike species, such as koalas, that have a highly specialized diet (for koalas, eucalyptus leaves). With our amazing dietary range comes a problem: the omnivore’s dilemma (Pollan, 2006; Rozin & Rozin, 1981). To survive, we must identify healthy food and avoid poisons. The senses of taste and smell cooperate to give us this ability. Smell also has other important functions in lower animals (e.g., avoid predators, identify sexual partners), but these functions are less important in humans. This module will focus on the way taste and smell interact in humans to solve the omnivore’s dilemma.

Taste and Smell Anatomy

Taste (gustation) and smell (olfaction) are both chemical senses; that is, the stimuli for these senses are chemicals. The more complex sense is olfaction. Olfactory receptors are complex proteins called G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). These structures are proteins that weave back and forth across the membranes of olfactory cells seven times, forming structures outside the cell that sense odorant molecules and structures inside the cell that activate the neural message ultimately conveyed to the brain by olfactory neurons. The structures that sense odorants can be thought of as tiny binding pockets with sites that respond to active parts of molecules (e.g., carbon chains). There are about 350 functional olfactory genes in humans; each gene expresses a particular kind of olfactory receptor. All olfactory receptors of a given kind project to structures called glomeruli (paired clusters of cells found on both sides of the brain). For a single molecule, the pattern of activation across the glomeruli paints a picture of the chemical structure of the molecule. Thus, the olfactory system can identify a vast array of chemicals present in the environment. Most of the odors we encounter are actually mixtures of chemicals (e.g., bacon odor). The olfactory system creates an image for the mixture and stores it in memory just as it does for the odor of a single molecule (Shepherd, 2005).

Taste is simpler than olfaction. Bitter and sweet utilize GPCRs, just as olfaction does, but the number of different receptors is much smaller. For bitter, 25 receptors are tuned to different chemical structures (Meyerhof et al., 2010). Such a system allows us to sense many different poisons.

Sweet is even simpler. The primary sweet receptor is composed of two different G protein-coupled receptors; each of these two proteins ends in large structures reminiscent of Venus flytraps. This complex receptor has multiple sites that can bind different structures. The Venus flytrap endings open so that even some very large molecules can fit inside and stimulate the receptor.

Bitter is inclusive (i.e., multiple receptors tuned to very different chemical structures feed into common neurons). Sweet is exclusive. There are many sugars with similar structures, but only three of these are particularly important to humans (sucrose, glucose, and fructose). Thus, our sweet receptor tunes out most sugars, leaving only the most important to stimulate the sweet receptor. However, the ability of the sweet receptor to respond to some non-sugars presents us with one of the great mysteries of taste. Several non-sugar molecules can stimulate the primary sweet receptor (e.g., saccharine, aspartame, cyclamate). These have given rise to the artificial sweetener industry, but their biological significance is unknown. What biological purpose is served by allowing these non-sugar molecules to stimulate the primary sweet receptor?

Some would have us believe that artificial sweeteners are a boon to those who want to lose weight. It seems like a no-brainer. Sugars have calories; saccharin does not. Theoretically, if we replace sugar with saccharin in our diets, we will lose weight. In fact, recent work showed that rats actually gained weight when saccharin was substituted for glucose (Swithers & Davidson, 2008). It turns out that substituting saccharin for sugar can increase appetite so more is eaten later. In addition, eating artificial sweeteners appears to alter metabolism, thus making losing weight even harder. So why did nature give us artificial sweeteners? We don’t know.

One more mystery about sweet deserves comment. The discovery of the sweet receptor was met with great excitement because many investigators had searched for it for years. The fact that this complex receptor had multiple sites to which different molecules could bind explained why many different molecules taste sweet. However, this is actually a serious problem. No matter what molecule stimulates this receptor, the neural output from that receptor is the same. This would mean that the sweetness of all sweet substances would have to be the same. Yet artificial sweeteners do not taste exactly like sugar. The answer may lie in the fact that one of the two proteins that makes up the receptor can act alone, but only strong concentrations of sugar stimulate this isolated protein receptor. This permits the brain to distinguish between the sweetness of sugar and the sweetness of non-sugar molecules.

Salty and sour are the simplest tastes; these stimuli ionize (break into positively and negatively charged particles). The first event in the transduction series is the movement of the positively charged particle through channels in the taste cell membrane (Chaudhari & Roper, 2010).

Solving the omnivore’s dilemma: Taste affect is hard-wired

The pleasure associated with sweet and salty and the displeasure associated with sour and bitter are hard-wired in the brain. Newborns love sweet (taste of mother’s milk) and hate bitter (poisons) immediately. The receptors mediating salty taste are not mature at birth in humans, but when they are mature a few weeks after birth, the baby likes dilute salt (although more concentrated salt will evoke stinging sensations that will be avoided). Sour is generally disliked (protecting against tissue damage from acid?), but to the amazement of many parents, some young children appear to actually like the sour candies available today; this may be related to the breadth of their experience with fruits (Liem & Mennella, 2003). This hard-wired affect is the most salient characteristic of taste and this is why we classify only those taste qualities with hard-wired affect as “basic tastes.”

Another contribution to the omnivore’s dilemma: Olfactory affect is learned

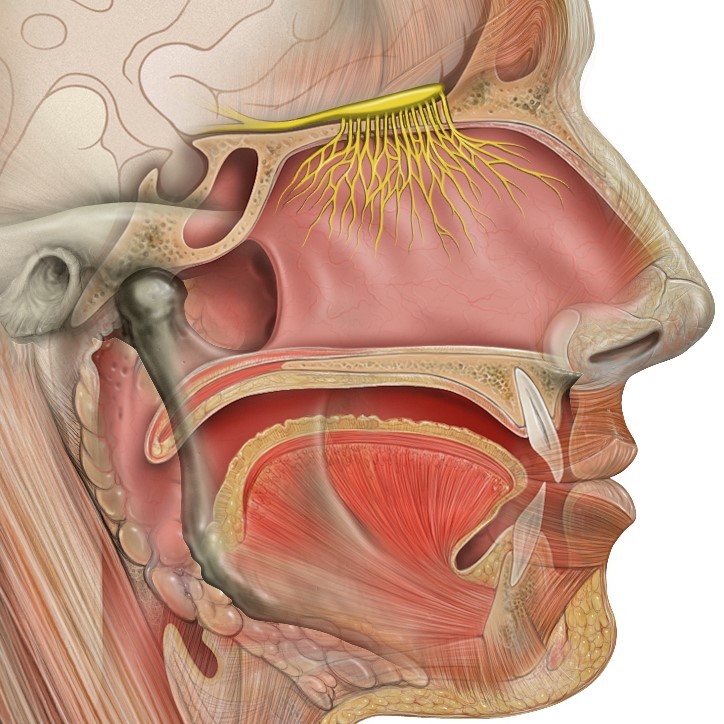

The biological functions of olfaction depend on how odors enter our noses. Sniffing brings odorants through our nostrils. The odorants hit the turbinate bones and a puff of the odorized air rises to the top of the nasal cavity, where it goes through a narrow opening (the olfactory cleft) and arrives at the olfactory mucosa (the tissue that houses the olfactory receptors). Technically, this is called “orthonasal olfaction.” Orthonasal olfaction tells us about the world external to our bodies.

When we chew and swallow food, the odorants emitted by the food are forced up behind the palate (roof of the mouth) and enter our noses from the back; this is called “retronasal olfaction.” Ortho and retronasal olfaction involve the same odor molecules and the same olfactory receptors; however, the brain can tell the difference between the two and does not send the input to the same areas. Retronasal olfaction and taste project to some common areas where they are presumably integrated into flavor. Flavors tell us about the food we are eating.

If retronasal olfaction is paired with nausea, the food evoking the retronasal olfactory sensation becomes disliked. If retronasal olfaction is paired with situations the brain deems valuable (calories, sweet taste, pleasure from other sources, etc.), the food evoking that sensation becomes liked. These are called conditioned aversions and preferences (Rozin & Vollmecke, 1986).

Those who have experienced a conditioned aversion may have found that the dislike (even disgust) evoked when a flavor is paired with nausea can generalize to the smell of the food alone (orthonasal olfaction). Some years ago, Jeremy Wolfe and Linda Bartoshuk surveyed conditioned aversions among college students and staff that had resulted from consuming foods/beverages associated with nausea (Bartoshuk & Wolfe, 1990). In 29% of the aversions, subjects reported that even the smell of the food/beverage had become aversive. Other properties of food objects can become aversive as well. In one unusual case, an aversion to cheese crackers generalized to vanilla wafers apparently because the containers were similar. Conditioned aversions function to protect us from ingesting a food that our brains associate with illness. Conditioned preferences are harder to form, but they help us learn what is safe to eat.

Is the affect associated with olfaction ever hard-wired? Pheromones are said to be olfactory molecules that evoke specific behaviors. Googling “human pheromone” will take you to websites selling various sprays that are supposed to make one more sexually appealing. However, careful research does not support such claims in humans or any other mammals (Doty, 2010). For example, amniotic fluid was at one time believed to contain a pheromone that attracted rat pups to their mother’s nipples so they could suckle. Early interest in identifying the molecule that acted as that pheromone gave way to understanding that the behavior was learned when a novel odorant, citral (which smells like lemons), was easily substituted for amniotic fluid (Pedersen, Williams, & Blass, 1982).

Central interactions: Key to understanding taste damage

The integration of retronasal olfaction and taste into flavor is not the only central interaction among the sensations evoked by foods. These integrations in most cases serve important biological functions, but occasionally they go awry and lead to clinical pathologies.

Taste is mediated by three cranial nerves; these are bilateral nerves, each of which innervates one side of the mouth. Since they do not connect in the peripheral nervous system, interactions across the midline must occur in the brain. Incidentally, studying interactions across the midline is a classic way to draw inferences about central interactions. Insights from studies of this type were very important to understanding central processes long before we had direct imaging of brain function.

Taste on the anterior two thirds of the tongue (the part you can stick out) is mediated by the chorda tympani nerve; taste on the posterior one third (the part that stays attached) is mediated by the glossopharyngeal nerve. Taste buds are tiny clusters of cells (like the segments of an orange) that are buried in the tissue of some papillae, the structures that give the tongue its bumpy appearance. Filiform papillae are the smallest and are distributed all over the tongue; they have no taste buds. In species like the cat, the filiform papillae are shaped like small spoons and help the cat hold liquids on the tongue while lapping (try lapping from a dish and you will see how hard it is without those special filiform papillae). Fungiform papillae (given this name because they resemble small button mushrooms) are larger circular structures on the anterior tongue (innervated by the chorda tympani). They contain about six taste buds each. Fungiform papillae can be seen with the naked eye, but swabbing blue food coloring on the tongue helps. The fungiform papillae do not stain as well as the rest of the tongue so they look like pink circles against a blue background. On some tongues, the spacing of fungiform papillae is like polka dots. Other tongues can have 10 times as many fungiform papillae, spaced so closely that there is little space between them. There is a connection between the density of fungiform papillae and the perception of taste. Those who experience the most intense taste sensations (we call them supertasters) tend to have the most fungiform papillae. Incidentally, this is a rare example in sensory processes of visible anatomical variation that correlates with function. We can look at the tongues of a variety of individuals and predict which of them will experience the most intense taste sensations.

The structures that house taste buds innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve are called circumvallate papillae. They are relatively large structures arrayed in an inverted V shape across the back of the tongue. Each of them looks like a small island surrounded by a moat.

Taste nerves project to the brain, where they send inhibitory signals to one another. One of the biological consequences of this inhibition is taste constancy. Damage to one nerve reduces taste input but also reduces inhibition on the other nerves (Bartoshuk et al 2005). That release of inhibition intensifies the central neural signals from the undamaged nerves, thereby maintaining whole mouth function. Interestingly, this release of inhibition can be so powerful that it actually increases whole mouth taste. The small effect of limited taste damage is one of the earliest clinical observations. In 1825, Brillat-Savarin described in his book The Physiology of Taste an interview with an ex-prisoner who had suffered a horrible punishment: amputation of his tongue. “This man, whom I met in Amsterdam, where he made his living by running errands, had had some education, and it was easy to communicate with him by writing. After I had observed that the forepart of his tongue has been cut off clear to the ligament, I asked him if he still found any flavor in what he ate, and if his sense of taste had survived the cruelty to which he had been subjected. He replied that … he still possessed the ability to taste fairly well” (Brillat-Savarin, 1971, pg. 35). This injury damaged the chorda tympani but spared the glossopharyngeal nerve.

We now know that taste nerves not only inhibit one another but also inhibit other oral sensations. Thus, taste damage can intensify oral touch (fats) and oral burn (chilis). In fact, taste damage appears to be linked to pain in general. Consider an animal injured in the wild. If pain reduced eating, its chance of survival would be diminished. However, nature appears to have wired the brain such that taste input inhibits pain. Eating is reinforced and the animal’s chances of survival increase.

Taste damage and weight gain

The effects of taste damage depend on the extent of damage. If only one taste nerve is damaged, then release of inhibition occurs. If the damage is extensive enough, function is lost with one possible exception. Preliminary data suggest that the more extensive the damage to taste, the greater the intensification of pain; this is obviously of clinical interest.

Damage to a single taste nerve can intensify oral touch (e.g., the creamy, viscous sensations evoked by fats). Perhaps most surprising, damage to a single taste nerve can intensify retronasal olfaction; this may occur as a secondary result from the intensification of whole mouth taste.

These sensory changes can alter the palatability of foods; in particular, high-fat foods can be rendered more palatable. Thus one of the first areas we examined was the possibility that mild taste damage could lead to increases in body mass index. Middle ear infections (otitis media) can damage the chorda tympani nerve; a tonsillectomy can damage the glossopharyngeal nerve. Head trauma damages both nerves, although it tends to take its greatest toll on the chorda tympani nerve. All of these clinical conditions increase body mass index in some individuals. More work is needed, but we suspect a link between the intensification of fat sensations, enhancement of palatability of high-fat foods, and weight gain.

Outside Resources

- Video: Inside the Psychologists Studio with Linda Bartoshuk

- Video: Linda Bartoshuk at Nobel Conference 46

- Video: Test your tongue: the science of taste

Discussion Questions

- In this module, we have defined “basic tastes” in terms of whether or not a sensation produces hard-wired affect. Can you think of any other definitions of basic tastes?

- Do you think omnivores, herbivores, or carnivores have a better chance at survival?

- Olfaction is mediated by one cranial nerve. Taste is mediated by three cranial nerves. Why do you think evolution gave more nerves to taste than to smell? What are the consequences of this?

Vocabulary

- Conditioned aversions and preferences

- Likes and dislikes developed through associations with pleasurable or unpleasurable sensations.

- Gustation

- The action of tasting; the ability to taste.

- Olfaction

- The sense of smell; the action of smelling; the ability to smell.

- Omnivore

- A person or animal that is able to survive by eating a wide range of foods from plant or animal origin.

- Orthonasal olfaction

- Perceiving scents/smells introduced via the nostrils.

- Retronasal olfaction

- Perceiving scents/smells introduced via the mouth/palate.

References

- Bartoshuk, L. M., & Wolfe, J. M. (1990). Conditioned taste aversions in humans: Are they olfactory aversions? (abstract). Chemical Senses, 15, 551.

- Bartoshuk, L. M., Snyder, D. J., Grushka, M., Berger, A. M., Duffy, V. B,, & Kveton, J. F. (2005). Taste damage: previously unsuspected consequences. Chemical Senses, 30(Suppl. 1), i218–i219

- Brillat-Savarin, J. A. (1825). The physiology of taste (M.F.K. Fisher, Trans., 1971). New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Chaudhari, N., & Roper, S. D. (2010). The cell biology of taste. Journal of Cell Biology, 190, 285–296.

- Doty, R. L. (2010). The great pheromone myth. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Liem, D. G., & Mennella, J. A. (2003). Heightened sour preferences during childhood. Chemical Senses, 28(2), 173–180.

- Meyerhof, W., Batram, C., Kuhn, C., Brockhoff, A., Chudoba, E., Bufe, B., . . . Behrens, M. (2010). The molecular receptive ranges of human TAS2R bitter taste receptors. Chemical Senses, 35, 157–170.

- Pedersen, P.E., Williams, C.L., & Blass, E.M. (1982). Activation and odor conditioning of suckling behavior in 3-day-old albino rats. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes, 8(4), 329–341.

- Pollan, M. (2006). The omnivore's dilemma. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

- Rozin, E., & Rozin, P. (1981). Culinary themes and variations. Natural History, 90, 6–14.

- Rozin, P., & Vollmecke, T.A. (1986). Food likes and dislikes. Annual Review of Nutrition, 6, 433-456.

- Shepherd, G. M. (2005). Outline of a theory of olfactory processing and its relevance to humans. Chemical Senses, 30(Suppl 1), i3-i5.

- Swithers, S. E., & Davidson, T. L. (2008). A role for sweet taste: Calorie predictive relations in energy regulation by rats. Behavioral Neuroscience, 122(1), 161-173.