2.3: Psychological Perspectives

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 161408

- Alexis Bridley and Lee W. Daffin Jr.

- Washington State University

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Describe the psychodynamic theory.

- Outline the structure of personality and how it develops over time.

- Describe ways to deal with anxiety.

- Clarify what psychodynamic techniques are used.

- Evaluate the usefulness of psychodynamic theory.

- Describe learning.

- Outline respondent conditioning and the work of Pavlov and Watson.

- Outline operant conditioning and the work of Thorndike and Skinner.

- Outline observational learning/social-learning theory and the work of Bandura.

- Evaluate the usefulness of the behavioral model.

- Define the cognitive model.

- Exemplify the effect of schemas on creating abnormal behavior.

- Exemplify the effect of attributions on creating abnormal behavior.

- Exemplify the effect of maladaptive cognitions on creating abnormal behavior.

- List and describe cognitive therapies.

- Evaluate the usefulness of the cognitive model.

- Describe the humanistic perspective.

- Describe the existential perspective.

- Evaluate the usefulness of humanistic and existential perspectives.

Psychodynamic Theory

In 1895, the book, Studies on Hysteria, was published by Josef Breuer (1842-1925) and Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), and marked the birth of psychoanalysis, though Freud did not use this actual term until a year later. The book published several case studies, including that of Anna O., born February 27, 1859 in Vienna to Jewish parents Siegmund and Recha Pappenheim, strict Orthodox adherents who were considered millionaires at the time. Bertha, known in published case studies as Anna O., was expected to complete the formal education typical of upper-middle-class girls, which included foreign language, religion, horseback riding, needlepoint, and piano. She felt confined and suffocated in this life and took to a fantasy world she called her “private theater.” Anna also developed hysteria, including symptoms such as memory loss, paralysis, disturbed eye movements, reduced speech, nausea, and mental deterioration. Her symptoms appeared as she cared for her dying father, and her mother called on Breuer to diagnosis her condition (note that Freud never actually treated her). Hypnosis was used at first and relieved her symptoms, as it had done for many patients (See Module 1). Breuer made daily visits and allowed her to share stories from her private theater, which she came to call “talking cure” or “chimney sweeping.” Many of the stories she shared were actually thoughts or events she found troubling and reliving them helped to relieve or eliminate the symptoms. Breuer’s wife, Mathilde, became jealous of her husband’s relationship with the young girl, leading Breuer to terminate treatment in June of 1882 before Anna had fully recovered. She relapsed and was admitted to Bellevue Sanatorium on July 1, eventually being released in October of the same year. With time, Anna O. did recover from her hysteria and went on to become a prominent member of the Jewish Community, involving herself in social work, volunteering at soup kitchens, and becoming ‘House Mother’ at an orphanage for Jewish girls in 1895. Bertha (Anna O.) became involved in the German Feminist movement, and in 1904 founded the League of Jewish Women. She published many short stories; a play called Women’s Rights, in which she criticized the economic and sexual exploitation of women; and wrote a book in 1900 called The Jewish Problem in Galicia, in which she blamed the poverty of the Jews of Eastern Europe on their lack of education. In 1935, Bertha was diagnosed with a tumor, and in 1936, she was summoned by the Gestapo to explain anti-Hitler statements she had allegedly made. She died shortly after this interrogation on May 28, 1936. Freud considered the talking cure of Anna O. to be the origin of psychoanalytic therapy and what would come to be called the cathartic method.

For more on Anna O., please see:

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/freuds-patients-serial/201201/bertha-pappenheim-1859-1936

2.3.1.1. The structure of personality. Freud’s psychoanalysis was unique in the history of psychology because it did not arise within universities as most major schools of thought did; rather, it emerged from medicine and psychiatry to address psychopathology and examine the unconscious. Freud believed that consciousness had three levels – 1) consciousness which was the seat of our awareness, 2) preconscious that included all of our sensations, thoughts, memories, and feelings, and 3) the unconscious, which was not available to us. The contents of the unconscious could move from the unconscious to preconscious, but to do so, it had to pass a Gate Keeper. Content that was turned away was said to be repressed.

According to Freud, our personality has three parts – the id, superego, and ego, and from these our behavior arises. First, the id is the impulsive part that expresses our sexual and aggressive instincts. It is present at birth, completely unconscious, and operates on the pleasure principle, resulting in selfishly seeking immediate gratification of our needs no matter what the cost. The second part of personality emerges after birth with early formative experiences and is called the ego. The ego attempts to mediate the desires of the id against the demands of reality, and eventually, the moral limitations or guidelines of the superego. It operates on the reality principle, or an awareness of the need to adjust behavior, to meet the demands of our environment. The last part of the personality to develop is the superego, which represents society’s expectations, moral standards, rules, and represents our conscience. It leads us to adopt our parent’s values as we come to realize that many of the id’s impulses are unacceptable. Still, we violate these values at times and experience feelings of guilt. The superego is partly conscious but mostly unconscious, and part of it becomes our conscience. The three parts of personality generally work together well and compromise, leading to a healthy personality, but if the conflict is not resolved, intrapsychic conflicts can arise and lead to mental disorders.

Personality develops over five distinct stages in which the libido focuses on different parts of the body. First, libido is the psychic energy that drives a person to pleasurable thoughts and behaviors. Our life instincts, or Eros, are manifested through it and are the creative forces that sustain life. They include hunger, thirst, self-preservation, and sex. In contrast, Thanatos, our death instinct, is either directed inward as in the case of suicide and masochism or outward via hatred and aggression. Both types of instincts are sources of stimulation in the body and create a state of tension that is unpleasant, thereby motivating us to reduce them. Consider hunger, and the associated rumbling of our stomach, fatigue, lack of energy, etc., that motivates us to find and eat food. If we are angry at someone, we may engage in physical or relational aggression to alleviate this stimulation.

2.3.1.2. The development of personality. Freud’s psychosexual stages of personality development are listed below. Please note that a person may become fixated at any stage, meaning they become stuck, thereby affecting later development and possibly leading to abnormal functioning, or psychopathology.

- Oral Stage – Beginning at birth and lasting to 24 months, the libido is focused on the mouth. Sexual tension is relieved by sucking and swallowing at first, and then later by chewing and biting as baby teeth come in. Fixation is linked to a lack of confidence, argumentativeness, and sarcasm.

- Anal Stage – Lasting from 2-3 years, the libido is focused on the anus as toilet training occurs. If parents are too lenient, children may become messy or unorganized. If parents are too strict, children may become obstinate, stingy, or orderly.

- Phallic Stage – Occurring from about age 3 to 5-6 years, the libido is focused on the genitals, and children develop an attachment to the parent of the opposite sex and are jealous of the same-sex parent. The Oedipus complex develops in boys and results in the son falling in love with his mother while fearing that his father will find out and castrate him. Meanwhile, girls fall in love with the father and fear that their mother will find out, called the Electra complex. A fixation at this stage may result in low self-esteem, feelings of worthlessness, and shyness.

- Latency Stage – From 6-12 years of age, children lose interest in sexual behavior, so boys play with boys and girls with girls. Neither sex pays much attention to the opposite sex.

- Genital Stage – Beginning at puberty, sexual impulses reawaken and unfulfilled desires from infancy and childhood can be satisfied during lovemaking.

2.3.1.3. Dealing with anxiety. The ego has a challenging job to fulfill, balancing both the will of the id and the superego, and the overwhelming anxiety and panic this creates. Ego-defense mechanisms are in place to protect us from this pain but are considered maladaptive if they are misused and become our primary way of dealing with stress. They protect us from anxiety and operate unconsciously by distorting reality. Defense mechanisms include the following:

- Repression – When unacceptable ideas, wishes, desires, or memories are blocked from consciousness such as forgetting a horrific car accident that you caused. Eventually, though, it must be dealt with, or the repressed memory can cause problems later in life.

- Reaction formation – When an impulse is repressed and then expressed by its opposite. For example, you are angry with your boss but cannot lash out at him, so you are super friendly instead. Another example is having lustful thoughts about a coworker than you cannot express because you are married, so you are extremely hateful to this person.

- Displacement – When we satisfy an impulse with a different object because focusing on the primary object may get us in trouble. A classic example is taking out your frustration with your boss on your wife and/or kids when you get home. If you lash out at your boss, you could be fired. The substitute target is less dangerous than the primary target.

- Projection – When we attribute threatening desires or unacceptable motives to others. An example is when we do not have the skills necessary to complete a task, but we blame the other members of our group for being incompetent and unreliable.

- Sublimation – When we find a socially acceptable way to express a desire. If we are stressed out or upset, we may go to the gym and box or lift weights. A person who desires to cut things may become a surgeon.

- Denial – Sometimes, life is so hard that all we can do is deny how bad it is. An example is denying a diagnosis of lung cancer given by your doctor.

- Identification – When we find someone who has found a socially acceptable way to satisfy their unconscious wishes and desires, and we model that behavior.

- Regression – When we move from a mature behavior to one that is infantile. If your significant other is nagging you, you might regress by putting your hands over your ears and saying, “La la la la la la la la…”

- Rationalization – When we offer well-thought-out reasons for why we did what we did, but these are not the real reason. Students sometimes rationalize not doing well in a class by stating that they really are not interested in the subject or saying the instructor writes impossible-to-pass tests.

- Intellectualization – When we avoid emotion by focusing on the intellectual aspects of a situation such as ignoring the sadness we are feeling after the death of our mother by focusing on planning the funeral.

For more on defense mechanisms, please visit:

2.3.1.4. Psychodynamic techniques. Freud used three primary assessment techniques—free association, transference, and dream analysis—as part of psychoanalysis, or psychoanalytic therapy, to understand the personalities of his patients and expose repressed material. First, free association involves the patient describing whatever comes to mind during the session. The patient continues but always reaches a point when he/she cannot or will not proceed any further. The patient might change the subject, stop talking, or lose his/her train of thought. Freud said this resistance revealed where issues persisted.

Second, transference is the process through which patients transfer attitudes he/she held during childhood to the therapist. They may be positive and include friendly, affectionate feelings, or negative, and include hostile and angry feelings. The goal of therapy is to wean patients from their childlike dependency on the therapist.

Finally, Freud used dream analysis to understand a person’s innermost wishes. The content of dreams includes the person’s actual retelling of the dreams, called manifest content, and the hidden or symbolic meaning called latent content. In terms of the latter, some symbols are linked to the person specifically, while others are common to all people.

2.3.1.5. Evaluating psychodynamic theory. Freud’s psychodynamic theory made a lasting impact on the field of psychology but also has been criticized heavily. First, Freud made most of his observations in an unsystematic, uncontrolled way, and he relied on the case study method. Second, the participants in his studies were not representative of the broader population. Despite Freud’s generalization, his theory was based on only a few patients. Third, he relied solely on the reports of his patients and sought no observer reports. Fourth, it is difficult to empirically study psychodynamic principles since most operate unconsciously. This begs the question of how we can really know that they exist. Finally, psychoanalytic treatment is expensive and time consuming, and since Freud’s time, drug therapies have become more popular and successful. Still, Sigmund Freud developed useful therapeutic tools for clinicians and raised awareness about the role the unconscious plays in both normal and abnormal behavior.

The Behavioral Model

2.3.2.1. What is learning? The behavioral model concerns the cognitive process of learning, which is any relatively permanent change in behavior due to experience and practice. Learning has two main forms – associative learning and observational learning. First, associative learning is the linking together of information sensed from our environment. Conditioning, or a type of associative learning, occurs when two separate events become connected. There are two forms: classical conditioning, or linking together two types of stimuli, and operant conditioning, or linking together a response with its consequence. Second, observational learning occurs when we learn by observing the world around us.

We should also note the existence of non-associative learning or when there is no linking of information or observing the actions of others around you. Types include habituation, or when we simply stop responding to repetitive and harmless stimuli in our environment such as a fan running in your laptop as you work on a paper, and sensitization, or when our reactions are increased due to a strong stimulus, such as an individual who experienced a mugging and now panics when someone walks up behind him/her on the street.

Behaviorism is the school of thought associated with learning that began in 1913 with the publication of John B. Watson’s article, “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It,” in the journal Psychological Review (Watson, 1913). Watson believed that the subject matter of psychology was to be observable behavior, and to that end, psychology should focus on the prediction and control of behavior. Behaviorism was dominant from 1913 to 1990 before being absorbed into mainstream psychology. It went through three major stages – behaviorism proper under Watson and lasting from 1913-1930 (discussed as classical/respondent conditioning), neobehaviorism under Skinner and lasting from 1930-1960 (discussed as operant conditioning), and sociobehaviorism under Bandura and Rotter and lasting from 1960-1990 (discussed as social learning theory).

2.3.2.2. Respondent conditioning. You have likely heard about Pavlov and his dogs, but what you may not know is that this was a discovery made accidentally. Ivan Petrovich Pavlov (1906, 1927, 1928), a Russian physiologist, was interested in studying digestive processes in dogs in response to being fed meat powder. What he discovered was the dogs would salivate even before the meat powder was presented. They would salivate at the sound of a bell, footsteps in the hall, a tuning fork, or the presence of a lab assistant. Pavlov realized some stimuli automatically elicited responses (such as salivating to meat powder) and other stimuli had to be paired with these automatic associations for the animal or person to respond to it (such as salivating to a bell). Armed with this stunning revelation, Pavlov spent the rest of his career investigating the learning phenomenon.

The important thing to understand is that not all behaviors occur due to reinforcement and punishment as operant conditioning says. In the case of respondent conditioning, stimuli exert complete and automatic control over some behaviors. We see this in the case of reflexes. When a doctor strikes your knee with that little hammer, your leg extends out automatically. Another example is how a baby will root for a food source if the mother’s breast is placed near their mouth. And if a nipple is placed in their mouth, they will also automatically suck via the sucking reflex. Humans have several of these reflexes, though not as many as other animals due to our more complicated nervous system.

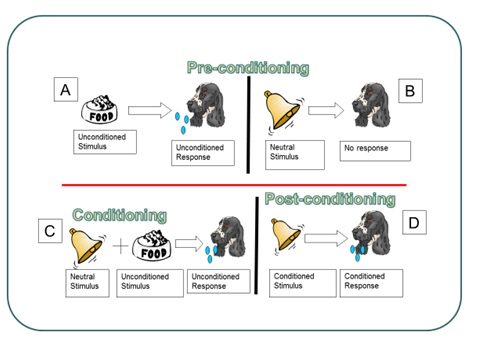

Respondent conditioning (also called classical or Pavlovian conditioning) occurs when we link a previously neutral stimulus with a stimulus that is unlearned or inborn, called an unconditioned stimulus. In respondent conditioning, learning happens in three phases: preconditioning, conditioning, and postconditioning. See Figure 2.5 for an overview of Pavlov’s classic experiment.

Preconditioning. Notice that preconditioning has both an A and a B panel. All this stage of learning signifies is that some learning is already present. There is no need to learn it again, as in the case of primary reinforcers and punishers in operant conditioning. In Panel A, food makes a dog salivate. This response does not need to be learned and shows the relationship between an unconditioned stimulus (UCS) yielding an unconditioned response (UCR). Unconditioned means unlearned. In Panel B, we see that a neutral stimulus (NS) produces no response. Dogs do not enter the world knowing to respond to the ringing of a bell (which it hears).

Conditioning. Conditioning is when learning occurs. By pairing a neutral stimulus and unconditioned stimulus (bell and food, respectively), the dog will learn that the bell ringing (NS) signals food coming (UCS) and salivate (UCR). The pairing must occur more than once so that needless pairings are not learned such as someone farting right before your food comes out and now you salivate whenever someone farts (…at least for a while. Eventually the fact that no food comes will extinguish this reaction but still, it will be weird for a bit).

Figure 2.5. Pavlov’s Classic Experiment

Postconditioning. Postconditioning, or after learning has occurred, establishes a new and not naturally occurring relationship of a conditioned stimulus (CS; previously the NS) and conditioned response (CR; the same response). So the dog now reliably salivates at the sound of the bell because he expects that food will follow, and it does.

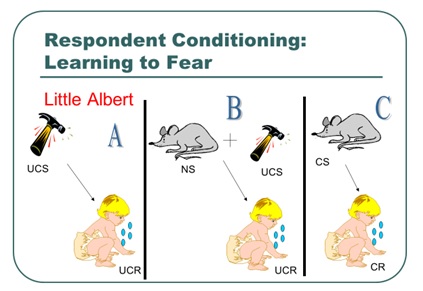

Watson and Rayner (1920) conducted one of the most famous studies in psychology. Essentially, they wanted to explore “the possibility of conditioning various types of emotional response(s).” The researchers ran a series of trials in which they exposed a 9-month-old child, known as Little Albert, to a white rat. Little Albert made no response outside of curiosity (NS–NR not shown). Panel A of Figure 2.6 shows the naturally occurring response to the stimulus of a loud sound. On later trials, the rat was presented (NS) and followed closely by a loud sound (UCS; Panel B). After several conditioning trials, the child responded with fear to the mere presence of the white rat (Panel C).

Figure 2.6. Learning to Fear

As fears can be learned, so too they can be unlearned. Considered the follow-up to Watson and Rayner (1920), Jones (1924; Figure 2.7) wanted to see if a child who learned to be afraid of white rabbits (Panel B) could be conditioned to become unafraid of them. Simply, she placed the child in one end of a room and then brought in the rabbit. The rabbit was far enough away so as not to cause distress. Then, Jones gave the child some pleasant food (i.e., something sweet such as cookies [Panel C]; remember the response to the food is unlearned, i.e., Panel A). The procedure in Panel C continued with the rabbit being brought a bit closer each time until, eventually, the child did not respond with distress to the rabbit (Panel D).

Figure 2.7. Unlearning Fears

This process is called counterconditioning, or the reversal of previous learning.

Another respondent conditioning way to unlearn a fear is called flooding or exposing the person to the maximum level of stimulus and as nothing aversive occurs, the link between CS and UCS producing the CR of fear should break, leaving the person unafraid. That is the idea, at least. So, if you were afraid of clowns, you would be thrown into a room full of clowns. Hmm….

Finally, respondent conditioning has several properties:

- Respondent Generalization – When many similar CSs or a broad range of CSs elicit the same CR. An example is the sound of a whistle eliciting salivation much the same as a ringing bell, both detected via audition.

- Respondent Discrimination – When a single CS or a narrow range of CSs elicits a CR, i.e., teaching the dog to respond to a specific bell and ignore the whistle. The whistle would not be followed by food, eventually leading to….

- Respondent Extinction – When the CS is no longer paired with the UCS. The sound of a school bell ringing (new CS that was generalized) is not followed by food (UCS), and so eventually, the dog stops salivating (the CR).

- Spontaneous Recovery – When the CS elicits the CR after extinction has occurred. Eventually, the school bell will ring, making the dog salivate. If no food comes, the behavior will not continue. If food appears, the salivation response will be re-established.

2.3.2.3. Operant conditioning. Influential on the development of Skinner’s operant conditioning, Thorndike (1905) proposed the law of effect or the idea that if our behavior produces a favorable consequence, in the future when the same stimulus is present, we will be more likely to make the response again, expecting the same favorable consequence. Likewise, if our action leads to dissatisfaction, then we will not repeat the same behavior in the future. He developed the law of effect thanks to his work with a puzzle box. Cats were food deprived the night before the experimental procedure was to occur. The next morning, researchers placed a hungry cat in the puzzle box and set a small amount of food outside the box, just close enough to be smelled. The cat could escape the box and reach the food by manipulating a series of levers. Once free, the cat was allowed to eat some food before being promptly returned to the box. With each subsequent escape and re-insertion into the box, the cat became faster at correctly manipulating the levers. This scenario demonstrates trial and error learning or making a response repeatedly if it leads to success. Thorndike also said that stimulus and responses were connected by the organism, and this led to learning. This approach to learning was called connectionism.

Operant conditioning is a type of associate learning which focuses on consequences that follow a response or behavior that we make (anything we do or say) and whether it makes a behavior more or less likely to occur. This should sound much like what you just read about in terms of Thorndike’s work. Skinner talked about contingencies or when one thing occurs due to another. Think of it as an If-Then statement. If I do X, then Y will happen. For operant conditioning, this means that if I make a behavior, then a specific consequence will follow. The events (response and consequence) are linked in time.

What form do these consequences take? There are two main ways they can present themselves.

-

- Reinforcement – Due to the consequence, a behavior/response is strengthened and more likely to occur in the future.

- Punishment – Due to the consequence, a behavior/response is weakened and less likely to occur in the future.

Reinforcement and punishment can occur as two types – positive and negative. These words have no affective connotation to them, meaning they do not imply good or bad. Positive means that you are giving something – good or bad. Negative means that something is being taken away – good or bad. Check out the figure below for how these contingencies are arranged.

Figure 2.8. Contingencies in Operant Conditioning

Let’s go through each:

- Positive Punishment (PP) – If something bad or aversive is given or added, then the behavior is less likely to occur in the future. If you talk back to your mother and she slaps your mouth, this is a PP. Your response of talking back led to the consequence of the aversive slap being given to your face. Ouch!!!

- Positive Reinforcement (PR) – If something good is given or added, then the behavior is more likely to occur in the future. If you study hard and receive an A on your exam, you will be more likely to study hard in the future. Similarly, your parents may give you money for your stellar performance. Cha Ching!!!

- Negative Reinforcement (NR) – This is a tough one for students to comprehend because the terms seem counterintuitive, even though we experience NR all the time. NR is when something bad or aversive is taken away or subtracted due to your actions, making it that you will be more likely to make the same behavior in the future when the same stimulus presents itself. For instance, what do you do if you have a headache? If you take Tylenol and the pain goes away, you will likely take Tylenol in the future when you have a headache. NR can either result in current escape behavior or future avoidance behavior. What does this mean? Escape occurs when we are presently experiencing an aversive event and want it to end. We make a behavior and if the aversive event, like the headache, goes away, we will repeat the taking of Tylenol in the future. This future action is an avoidance event. We might start to feel a headache coming on and run to take Tylenol right away. By doing so, we have removed the possibility of the aversive event occurring, and this behavior demonstrates that learning has occurred.

- Negative Punishment (NP) – This is when something good is taken away or subtracted, making a behavior less likely in the future. If you are late to class and your professor deducts 5 points from your final grade (the points are something good and the loss is negative), you will hopefully be on time in all subsequent classes.

The type of reinforcer or punisher we use is crucial. Some are naturally occurring, while others need to be learned. We describe these as primary and secondary reinforcers and punishers. Primary refers to reinforcers and punishers that have their effect without having to be learned. Food, water, temperature, and sex, for instance, are primary reinforcers, while extreme cold or hot or a punch on the arm are inherently punishing. A story will illustrate the latter. When I was about eight years old, I would walk up the street in my neighborhood, saying, “I’m Chicken Little and you can’t hurt me.” Most ignored me, but some gave me the attention I was seeking, a positive reinforcer. So I kept doing it and doing it until one day, another kid grew tired of hearing about my other identity and punched me in the face. The pain was enough that I never walked up and down the street echoing my identity crisis for all to hear. This was a positive punisher that did not have to be learned, and definitely not one of my finer moments in life.

Secondary or conditioned reinforcers and punishers are not inherently reinforcing or punishing but must be learned. An example was the attention I received for saying I was Chicken Little. Over time I learned that attention was good. Other examples of secondary reinforcers include praise, a smile, getting money for working or earning good grades, stickers on a board, points, getting to go out dancing, and getting out of an exam if you are doing well in a class. Examples of secondary punishers include a ticket for speeding, losing television or video game privileges, ridicule, or a fee for paying your rent or credit card bill late. Really, the sky is the limit with reinforcers in particular.

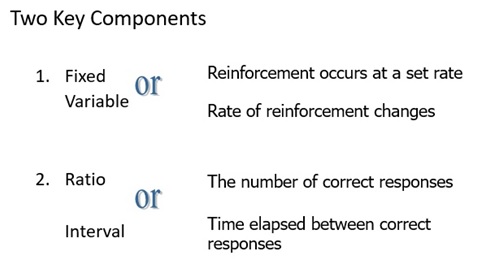

In operant conditioning, the rule for determining when and how often we will reinforce the desired behavior is called the reinforcement schedule. Reinforcement can either occur continuously meaning every time the desired behavior is made the subject will receive some reinforcer, or intermittently/partially meaning reinforcement does not occur with every behavior. Our focus will be on partial/intermittent reinforcement.

Figure 2.9. Key Components of Reinforcement Schedules

Figure 2.9 shows that that are two main components that make up a reinforcement schedule – when you will reinforce and what is being reinforced. In the case of when, it will be either fixed or at a set rate, or variable and at a rate that changes. In terms of what is being reinforced, we will either reinforce responses or time. These two components pair up as follows:

- Fixed Ratio schedule (FR) – With this schedule, we reinforce some set number of responses. For instance, every twenty problems (fixed) a student gets correct (ratio), the teacher gives him an extra credit point. A specific behavior is being reinforced – getting problems correct. Note that if we reinforce each occurrence of the behavior, the definition of continuous reinforcement, we could also describe this as an FR1 schedule. The number indicates how many responses have to be made, and in this case, it is one.

- Variable Ratio schedule (VR) – We might decide to reinforce some varying number of responses, such as if the teacher gives him an extra credit point after finishing between 40 and 50 correct problems. This approach is useful if the student is learning the material and does not need regular reinforcement. Also, since the schedule changes, the student will keep responding in the absence of reinforcement.

- Fixed Interval schedule (FI) – With a FI schedule, you will reinforce after some set amount of time. Let’s say a company wanted to hire someone to sell their product. To attract someone, they could offer to pay them $10 an hour 40 hours a week and give this money every two weeks. Crazy idea, but it could work. Saying the person will be paid every indicates fixed, and two weeks is time or interval. So, FI.

- Variable Interval schedule (VI) – Finally, you could reinforce someone at some changing amount of time. Maybe they receive payment on Friday one week, then three weeks later on Monday, then two days later on Wednesday, then eight days later on Thursday, etc. This could work, right? Not for a job, but maybe we could say we are reinforced on a VI schedule if we are.

Finally, four properties of operant conditioning – extinction, spontaneous recovery, stimulus generalization, and stimulus discrimination – are important. These are the same four discussed under respondent conditioning. First, extinction is when something that we do, say, think/feel has not been reinforced for some time. As you might expect, the behavior will begin to weaken and eventually stop when this occurs. Does extinction happen as soon as the anticipated reinforcer is removed? The answer is yes and no, depending on whether we are talking about continuous or partial reinforcement. With which type of schedule would you expect a person to stop responding to immediately if reinforcement is not there? Continuous or partial?

The answer is continuous. If a person is used to receiving reinforcement every time they perform a particular behavior, and then suddenly no reinforcer is delivered, he or she will cease the response immediately. Obviously then, with partial, a response continues being made for a while. Why is this? The person may think the schedule has simply changed. ‘Maybe I am not paid weekly now. Maybe it changed to biweekly and I missed the email.’ Due to this endurance, we say that intermittent or partial reinforcement shows resistance to extinction, meaning the behavior does weaken, but gradually.

As you might expect, if reinforcement occurs after extinction has started, the behavior will re-emerge. Consider your parents for a minute. To stop some undesirable behavior you made in the past, they likely took away some privilege. I bet the bad behavior ended too. But did you ever go to your grandparent’s house and grandma or grandpa—or worse, BOTH—took pity on you and let you play your video games (or something equivalent)? I know my grandmother used to. What happened to that bad behavior that had disappeared? Did it start again and your parents could not figure out why?

Additionally, you might have wondered if the person or animal will try to make the response again in the future even though it stopped being reinforced in the past. The answer is yes, and one of two outcomes is possible. First, the response is made, and nothing happens. In this case, extinction continues. Second, the response is made, and a reinforcer is delivered. The response re-emerges. Consider a rat trained to push a lever to receive a food pellet. If we stop providing the food pellets, in time, the rat will stop pushing the lever. If the rat pushes the lever again sometime in the future and food is delivered, the behavior spontaneously recovers. Hence, this phenomenon is called spontaneous recovery.

2.3.2.4. Observational learning. There are times when we learn by simply watching others. This is called observational learning and is contrasted with enactive learning, which is learning by doing. There is no firsthand experience by the learner in observational learning, unlike enactive. As you can learn desirable behaviors such as watching how your father bags groceries at the grocery store (I did this and still bag the same way today), you can learn undesirable ones too. If your parents resort to alcohol consumption to deal with stressors life presents, then you also might do the same. The critical part is what happens to the person modeling the behavior. If my father seems genuinely happy and pleased with himself after bagging groceries his way, then I will be more likely to adopt this behavior. If my mother or father consumes alcohol to feel better when things are tough, and it works, then I might do the same. On the other hand, if we see a sibling constantly getting in trouble with the law, then we may not model this behavior due to the negative consequences.

Albert Bandura conducted pivotal research on observational learning, and you likely already know all about it. Check out Figure 2.10 to see if you do. In Bandura’s experiment, children were first brought into a room to watch a video of an adult playing nicely or aggressively with a Bobo doll, which provided a model. Next, the children are placed in a room with several toys in it. The room contains a highly prized toy, but they are told they cannot play with it. All other toys are allowed, including a Bobo doll. Children who watched the aggressive model behaved aggressively with the Bobo doll while those who saw the gentle model, played nice. Both groups were frustrated when deprived of the coveted toy.

Figure 2.10. Bandura’s Classic Experiment

According to Bandura, all behaviors are learned by observing others, and we model our actions after theirs, so undesirable behaviors can be altered or relearned in the same way. Modeling techniques change behavior by having subjects observe a model in a situation that usually causes them some anxiety. By seeing the model interact nicely with the fear evoking stimulus, their fear should subside. This form of behavior therapy is widely used in clinical, business, and classroom situations. In the classroom, we might use modeling to demonstrate to a student how to do a math problem. In fact, in many college classrooms, this is exactly what the instructor does. In the business setting, a model or trainer demonstrates how to use a computer program or run a register for a new employee.

However, keep in mind that we do not model everything we see. Why? First, we cannot pay attention to everything going on around us. We are more likely to model behaviors by someone who commands our attention. Second, we must remember what a model does to imitate it. If a behavior is not memorable, it will not be imitated. We must try to convert what we see into action. If we are not motivated to perform an observed behavior, we probably will not show what we have learned.

2.3.2.5. Evaluating the behavioral model. Within the context of psychopathology, the behavioral perspective is useful because explains maladaptive behavior in terms of learning gone awry. The good thing is that what is learned can be unlearned or relearned through behavior modification, the process of changing behavior. To begin, an applied behavior analyst identifies a target behavior, or behavior to be changed, defines it, works with the client to develop goals, conducts a functional assessment to understand what the undesirable behavior is, what causes it, and what maintains it. With this knowledge, a plan is developed and consists of numerous strategies to act on one or all these elements – antecedent, behavior, and/or consequence. The strategies arise from all three learning models. In terms of operant conditioning, strategies include antecedent manipulations, prompts, punishment procedures, differential reinforcement, habit reversal, shaping, and programming. Flooding and desensitization are typical respondent conditioning procedures used with phobias, and modeling arises from social learning theory and observational learning. Watson and Skinner defined behavior as what we do or say, but later behaviorists added what we think or feel. In terms of the latter, cognitive behavior modification procedures arose after the 1960s and with the rise of cognitive psychology. This led to a cognitive-behavioral perspective that combines concepts from the behavioral and cognitive models, the latter discussed in the next section.

Critics of the behavioral perspective point out that it oversimplifies behavior and often ignores inner determinants of behavior. Behaviorism has also been accused of being mechanistic and seeing people as machines. This criticism would be true of behaviorism’s first two stages, though sociobehaviorism steered away from this proposition and even fought against any mechanistic leanings of behaviorists.

The greatest strength or appeal of the behavioral model is that its tenets are easily tested in the laboratory, unlike those of the psychodynamic model. Also, many treatment techniques have been developed and proven to be effective over the years. For example, desensitization (Wolpe, 1997) teaches clients to respond calmly to fear-producing stimuli. It begins with the individual learning a relaxation technique such as diaphragmatic breathing. Next, a fear hierarchy, or list of feared objects and situations, is constructed in which the individual moves from least to most feared. Finally, the individual either imagines (systematic) or experiences in real life (in-vivo) each object or scenario from the hierarchy and uses the relaxation technique while doing so. This represents the individual pairings of a feared object or situation and relaxation. So, if there are 10 objects/situations in the list, the client will experience ten such pairings and eventually be able to face each without fear. Outside of phobias, desensitization has been shown to be effective in the treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder symptoms (Hakimian and Souza, 2016) and limitedly with the treatment of depression when co-morbid with OCD (Masoumeh and Lancy, 2016).

The Cognitive Model

2.3.3.1. What is it? As noted earlier, the idea of people being machines, called mechanism, was a key feature of behaviorism and other schools of thought in psychology until about the 1960s or 1970s. In fact, behaviorism said psychology was to be the study of observable behavior. Any reference to cognitive processes was dismissed as this was not overt, but covert according to Watson and later Skinner. Of course, removing cognition from the study of psychology ignored an important part of what makes us human and separates us from the rest of the animal kingdom. Fortunately, the work of George Miller, Albert Ellis, Aaron Beck, and Ulrich Neisser demonstrated the importance of cognitive abilities in understanding thoughts, behaviors, and emotions, and in the case of psychopathology, show that people can create their problems by how they come to interpret events experienced in the world around them. How so?

2.3.3.2. Schemas and cognitive errors. First, consider the topic of social cognition or the process of collecting and assessing information about others. So what do we do with this information? Once collected or sensed (sensation is the cognitive process of detecting the physical energy given off or emitted by physical objects), the information is sent to the brain through the neural impulse. Once in the brain, it is processed and interpreted. This is where assessing information about others comes in and involves the cognitive process of perception, or adding meaning to raw sensory data. We take the information just detected and use it to assign people to categories, or groups. For each category, we have a schema, or a set of beliefs and expectations about a group of people, presumed to apply to all members of the group, and based on experience.

Can our schemas lead us astray or be false? Consider where students sit in a class. It is generally understood that the students who sit in the front of the class are the overachievers and want to earn an A in the class. Those who sit in the back of the room are underachievers who don’t care. Right? Where do you sit in class, if you are on a physical campus and not an online student? Is this correct? What about other students in the class that you know? What if you found out that a friend who sits in the front row is a C student but sits there because he cannot see the screen or board, even with corrective lenses? What about your friend or acquaintance in the back? This person is an A student but does not like being right under the nose of the professor, especially if he/she tends to spit when lecturing. The person in the back could also be shy and prefer sitting there so that s/he does not need to chat with others as much. Or, they are easily distracted and sits in the back so that all stimuli are in front of him/her. Again, your schema about front row and back row students is incorrect and causes you to make certain assumptions about these individuals. This might even affect how you interact with them. Would you want notes from the student in the front or back of the class?

2.3.3.3. Attributions and cognitive errors. Second, consider the very interesting social psychology topic attribution theory, or the idea that people are motivated to explain their own and other people’s behavior by attributing causes of that behavior to personal reasons or dispositional factors that are in the person themselves or linked to some trait they have; or situational factors that are linked to something outside the person. Like schemas, the attributions we make can lead us astray. How so? The fundamental attribution error occurs when we automatically assume a dispositional reason for another person’s actions and ignore situational factors. In other words, we assume the person who cut us off is an idiot (dispositional) and do not consider that maybe someone in the car is severely injured and this person is rushing them to the hospital (situational). Then there is the self-serving bias, which is when we attribute our success to our own efforts (dispositional) and our failures to external causes (situational). Our attribution in these two cases is in error, but still, it comes to affect how we see the world and our subjective well-being.

2.3.3.4. Maladaptive cognitions. Irrational thought patterns can be the basis of psychopathology. Throughout this book, we will discuss several treatment strategies used to change unwanted, maladaptive cognitions, whether they are present as an excess such as with paranoia, suicidal ideation, or feelings of worthlessness; or as a deficit such as with self-confidence and self-efficacy. More specifically, cognitive distortions/maladaptive cognitions can take the following forms:

- Overgeneralizing – You see a larger pattern of negatives based on one event.

- Mind Reading – Assuming others know what you are thinking without any evidence.

- What if? – Asking yourself ‘what if something happens,’ without being satisfied by any of the answers.

- Blaming – You focus on someone else as the source of your negative feelings and do not take any responsibility for changing yourself.

- Personalizing – Blaming yourself for adverse events rather than seeing the role that others play.

- Inability to disconfirm – Ignoring any evidence that may contradict your maladaptive cognition.

- Regret orientation – Focusing on what you could have done better in the past rather than on improving now.

- Dichotomous thinking – Viewing people or events in all-or-nothing terms.

2.3.3.5. Cognitive therapies. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), cognitive behavioral therapy “focuses on exploring relationships among a person’s thoughts, feelings and behaviors. During CBT a therapist will actively work with a person to uncover unhealthy patterns of thought and how they may be causing self-destructive behaviors and beliefs.” CBT attempts to identify negative or false beliefs and restructure them. They add, “Oftentimes someone being treated with CBT will have homework in between sessions where they practice replacing negative thoughts with more realistic thoughts based on prior experiences or record their negative thoughts in a journal.” For more on CBT, visit: https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Treatments/Psychotherapy. Some commonly used strategies include cognitive restructuring, cognitive coping skills training, and acceptance techniques.

First, you can use cognitive restructuring, also called rational restructuring, in which maladaptive cognitions are replaced with more adaptive ones. To do this, the client must be aware of the distressing thoughts, when they occur, and their effect on them. Next, help the client stop thinking these thoughts and replace them with more rational ones. It’s a simple strategy, but an important one. Psychology Today published a great article on January 21, 2013, which described four ways to change your thinking through cognitive restructuring. Briefly, these included:

- Notice when you are having a maladaptive cognition, such as making “negative predictions.” Figure out what is the worst thing that could happen and what alternative outcomes are possible.

- Track the accuracy of the thought. If you believe focusing on a problem generates a solution, then write down each time you ruminate and the result. You can generate a percentage of times you ruminated to the number of successful problem-solving strategies you generated.

- Behaviorally test your thought. Try figuring out if you genuinely do not have time to go to the gym by recording what you do each day and then look at open times of the day. Add them up and see if making some minor, or major, adjustments to your schedule will free an hour to get in some valuable exercise.

- Examine the evidence both for and against your thought. If you do not believe you do anything right, list evidence of when you did not do something right and then evidence of when you did. Then write a few balanced statements such as the one the article suggests, “I’ve made some mistakes that I feel embarrassed about, but a lot of the time, I make good choices.”

The article also suggested a few non-cognitive restructuring techniques, including mindfulness meditation and self-compassion. For more on these, visit: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/in-practice/201301/cognitive-restructuring

The second major CBT strategy is called cognitive coping skills training. This strategy teaches social skills, communication, assertiveness through direct instruction, role playing, and modeling. For social skills training, identify the appropriate social behavior such as making eye contact, saying no to a request, or starting up a conversation with a stranger and determine whether the client is inhibited from making this behavior due to anxiety. For communication, decide if the problem is related to speaking, listening, or both and then develop a plan for use in various interpersonal situations. Finally, assertiveness training aids the client in protecting their rights and obtaining what they want from others. Those who are not assertive are often overly passive and never get what they want or are unreasonably aggressive and only get what they want. Treatment starts with determining situations in which assertiveness is lacking and developing a hierarchy of assertiveness opportunities. Least difficult situations are handled first, followed by more difficult situations, all while rehearsing and mastering all the situations present in the hierarchy. For more on these techniques, visit http://cogbtherapy.com/cognitive-behavioral-therapy-exercises/.

Finally, acceptance techniques help reduce a client’s worry and anxiety. Life involves a degree of uncertainty, and at times we must accept this. Techniques might include weighing the pros and cons of fighting uncertainty or change. The disadvantages should outweigh the advantages and help you to end the struggle and accept what is unknown. Chances are you are already accepting the unknown in some areas of life and identifying these can help you to see why it is helpful in these areas, and how you can apply this in more difficult areas. Finally, does uncertainty always lead to a negative end? We may think so, but a review of the evidence for and against this statement will show that it does not and reduce how threatening it seems.

2.3.3.6. Evaluating the cognitive model. The cognitive model made up for an apparent deficit in the behavioral model – overlooking the role cognitive processes play in our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Right before his death, Skinner (1990) reminded psychologists that the only thing we can truly know and study was the observable. Cognitive processes cannot be empirically and reliably measured and should be ignored. Is there merit to this view? Social desirability states that sometimes participants do not tell us the truth about what they are thinking, feeling, or doing (or have done) because they do not want us to think less of them or to judge them harshly if they are outside the social norm. In other words, they present themselves in a favorable light. If this is true, how can we know anything about controversial matters? The person’s true intentions or thoughts and feelings are not readily available to us, or are covert, and do not make for useful empirical data. Still, cognitive-behavioral therapies have proven their efficacy for the treatment of OCD (McKay et al., 2015), perinatal depression (Sockol, 2015), insomnia (de Bruin et al., 2015), bulimia nervosa (Poulsen et al., 2014), hypochondriasis (Olatunji et al., 2014), and social anxiety disorder (Leichsenring et al., 2014) to name a few. Other examples will be discussed throughout this book.

The Humanistic and Existential Perspectives

2.3.4.1. The humanistic perspective. The humanistic perspective, or third force psychology (psychoanalysis and behaviorism being the other two forces), emerged in the 1960s and 1970s as an alternative viewpoint to the largely deterministic view of personality espoused by psychoanalysis and the view of humans as machines advocated by behaviorism. Key features of the perspective include a belief in human perfectibility, personal fulfillment, valuing self-disclosure, placing feelings over intellect, an emphasis on the present, and hedonism. Its key figures were Abraham Maslow, who proposed the hierarchy of needs, and Carl Rogers, who we will focus on here.

Rogers said that all people want to have positive regard from significant others in their life. When the individual is accepted as they are, they receive unconditional positive regard and become a fully functioning person. They are open to experience, live every moment to the fullest, are creative, accepts responsibility for their decisions, do not derive their sense of self from others, strive to maximize their potential, and are self-actualized. Their family and friends may disapprove of some of their actions but overall, respect and love them. They then realize their worth as a person but also that they are not perfect. Of course, most people do not experience this but instead are made to feel that they can only be loved and respected if they meet certain standards, called conditions of worth. Hence, they experience conditional positive regard. Their self-concept becomes distorted, now seen as having worth only when these significant others approve, leading to a disharmonious state and psychopathology. Individuals in this situation are unsure of what they feel, value, or need leading to dysfunction and the need for therapy. Rogers stated that the humanistic therapist should be warm, understanding, supportive, respectful, and accepting of his/her clients. This approach came to be called client-centered therapy.

2.3.4.2. The existential perspective. This approach stresses the need for people to re-create themselves continually and be self-aware, acknowledges that anxiety is a normal part of life, focuses on free will and self-determination, emphasizes that each person has a unique identity known only through relationships and the search for meaning, and finally, that we develop to our maximum potential. Abnormal behavior arises when we avoid making choices, do not take responsibility, and fail to actualize our full potential. Existential therapy is used to treat substance abuse, “excessive anxiety, apathy, alienation, nihilism, avoidance, shame, addiction, despair, depression, guilt, anger, rage, resentment, embitterment, purposelessness, psychosis, and violence. They also focus on life-enhancing experiences like relationships, love, caring, commitment, courage, creativity, power, will, presence, spirituality, individuation, self-actualization, authenticity, acceptance, transcendence, and awe.” For more information, please visit: https://www.psychologytoday.com/therapy-types/existential-therapy

2.3.4.3. Evaluating the humanistic and existential perspectives. The biggest criticism of these models is that the concepts are abstract and fuzzy and so very difficult to research. Rogers did try to investigate his propositions scientifically, but most other humanistic-existential psychologists rejected the use of the scientific method. They also have not developed much in the way of theory, and the perspectives tend to work best with people suffering from adjustment issues and not as well with severe mental illness. The perspectives do offer hope to people suffering tragedy by asserting that we control our destiny and can make our own choices.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- According to Freud, consciousness had three levels (consciousness, preconscious, and the unconscious), personality had three parts (the id, ego, and superego), personality developed over five stages (oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital), there are ten defense mechanisms to protect the ego such as repression and sublimation, and finally three assessment techniques (free association, transference, and dream analysis) could be used to understand the personalities of his patients and expose repressed material.

- The behavioral model concerns the cognitive process of learning, which is any relatively permanent change in behavior due to experience and practice and has two main forms – associative learning to include classical and operant conditioning and observational learning.

- Respondent conditioning (also called classical or Pavlovian conditioning) occurs when we link a previously neutral stimulus with a stimulus that is unlearned or inborn, called an unconditioned stimulus.

- Operant conditioning is a type of associate learning which focuses on consequences that follow a response or behavior that we make (anything we do, say, or think/feel) and whether it makes a behavior more or less likely to occur.

- Observational learning is learning by watching others and modeling techniques change behavior by having subjects observe a model in a situation that usually causes them some anxiety.

- The cognitive model focuses on schemas, cognitive errors, attributions, and maladaptive cognitions and offers strategies such as CBT, cognitive restructuring, cognitive coping skills training, and acceptance.

- The humanistic perspective focuses on positive regard, conditions of worth, and the fully functioning person while the existential perspective stresses the need for people to re-create themselves continually and be self-aware, acknowledges that anxiety is a normal part of life, focuses on free will and self-determination, emphasizes that each person has a unique identity known only through relationships and the search for meaning, and finally, that we develop to our maximum potential.

Review Questions

- What are the three parts of personality according to Freud?

- What are the five psychosexual stages according to Freud?

- List and define the ten defense mechanisms proposed by Freud.

- What are the three assessment techniques used by Freud?

- What is learning and what forms does it take?

- Describe respondent conditioning.

- Describe operant conditioning.

- Describe observational learning and modeling.

- How does the cognitive model approach psychopathology?

- How does the humanistic perspective approach psychopathology?

- How does the existential perspective approach psychopathology?