4.1: Humanising and democratising the IT revolution

- Page ID

- 125623

Humanising and democratising the IT revolution

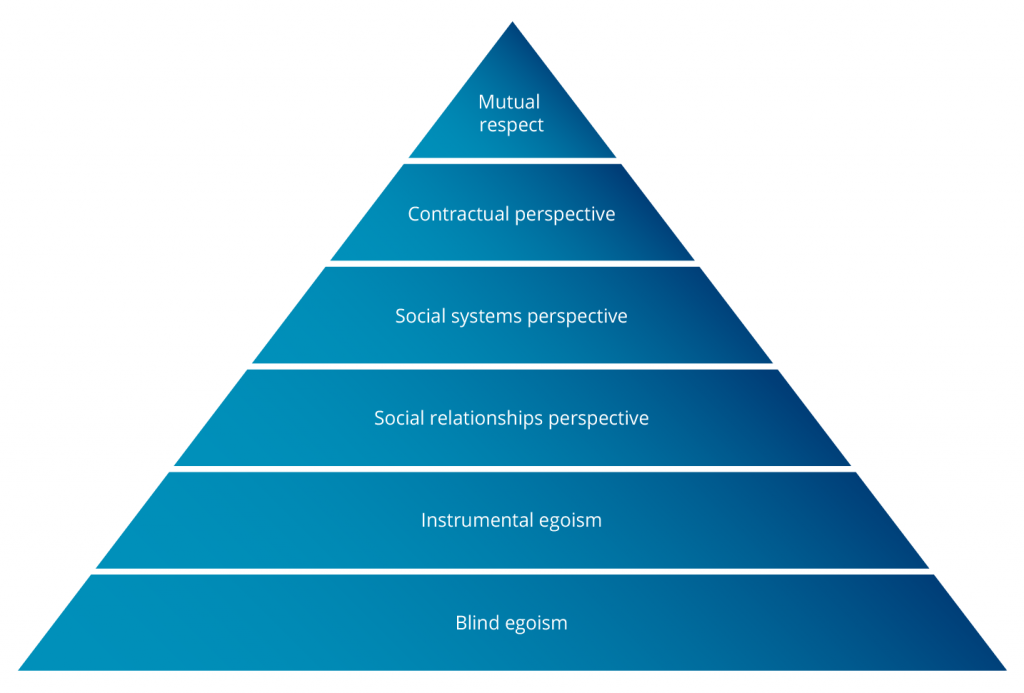

Bell (1997, p.218) summarises some of the features of these stages in the following way.

Stage 6: Universal principles of justice, the equality of human rights and respect for individual human dignity are deemed to transcend the law itself. In this view it is rational to believe that ‘doing the right thing’ is based on an understanding that universal moral principles are valid. Personal decisions to uphold such principles affirm their continued salience over time.

Stage 5: A contractual perspective requires impartial support for agreed core values, including that of trust in fulfilling contractual obligations. To this end it is helpful to recognise fundamental rights, such as the right to life and liberty, while not necessarily being constrained by fashion or transient opinion. Defensible ethical behaviour involves freely accepting such obligations and actively seeking the greatest benefit for the common good.

Stage 4: Embodies a focus on large and more dominant social institutions and the wider society as a whole. Group welfare is a primary concern, and it is in this context that obligations need to be fulfilled.

Stage 3: The need to be, and be seen as, a good person. Sustained loyalty is related primarily to particular groups and organisations. Individuals are keenly alert to the expectations of others in most situations. They are self-critical within these limited domains.

Stage 2: A bi-directional stance in which individuals pursue their own agendas while also remaining open to, and accepting of, those of others. Behaviour is, however, socially sanctioned since it is dependent upon on approval and reinforcement from others.

Stage 1: The locus of decision-making is largely external and, as such, lies beyond the individual. Motivation is therefore focused on routine, convergent behaviour and the avoidance of sanctions. ‘Doing right thing’ is identified with successfully following pre-existing rules and procedures.

It is for the reader to consider how well or badly the values and human qualities suggested here may apply to specific individuals and organisations that have colonised the Internet for their own limited purposes. But at the very least Bell and Kohlberg provide us with clear and reliable criteria that can legitimately be used as an evaluative scale. So in terms of moral development thus defined, some organisations and their executive leaders may find themselves hard pressed to provide adequate answers. Which has huge social implications. When the question of re-negotiating social contracts is raised – and it will be repeatedly – then interlocutors can legitimately seek evidence for the fulfilment of these criteria at the highest levels. Possibly the most useful guidance and overall summary is provided by Bell himself when he suggests that ‘ People live best who live for others as well as for themselves’ (Bell, 1997, p.275). Finally Figure 3 summarises some of the key suggestions made throughout this series back to an Integral perspective.

A straightforward four-quadrant analysis illustrates how various right hand quadrant phenomena (including technology, infrastructure and exterior actions) can usefully be related back to various left hand quadrant equivalents (values, worldviews, stages of development etc. as expressed through a variety of cultural norms and conditions). It follows that one way of promoting more humanised and democratic uses of any technology is to simply open to these left-hand quadrant realities and take them fully into account.

The story thus far has shown how the early Internet was shaped and conditioned by specific human and cultural forces within the U.S. After a fairly benign, government-funded start, a handful of entrepreneurs took over and, with little or no thought for wider consequences, actively fashioned the conditions for their own success. Tax laws were revised. Anti-trust regulations that had earlier been applied to Microsoft and the Bell Telephone Company were set aside. Strategies were undertaken through which private monopoly platforms would grow unhindered into the world-spanning behemoths of today. The rise of neoliberalism turbo-charged this process. Following Hayek, it viewed the government as an impediment to ‘progress’ and the market as an unquestioned good. These tendencies, along with Rand’s nihilistic view of human existence, all helped to bring the present constellation of rootless and invasive entities to its present condition.

In an alternative world, competent far-sighted governance would have set the conditions for such enterprises and modified them progressively over time. Human rights (including the right to dignity, privacy and freedom from oppression) would have been respected and consciously built into the foundations of the Internet. Corporations would have learned to respect users and therefore to ask before expropriating creative work and private data wholesale for commercial gain. Tax laws that mediated fairly between corporate and social needs would have helped to ensure a steady flow of income for social expenditures. When entities grew too large they would have been broken up or otherwise compelled to adapt. Currently, however, we do not live in that world.

Yet, as can be seen from some of the many examples outlined above, there are a host of reasons to support informed optimism and hope, the framing of real solutions. Furthermore, it is helpful to remember that some aspects of our situation are not entirely new. When Martin Luther hammered a copy of his 93 theses onto the Wittenberg church door some five centuries ago, he set himself against the oligarch of the day – the all-powerful Catholic Church. He questioned the legitimacy of that vast institution and, at the same time, began a process that both destroyed its business model and made way for alternatives. Today the underlying dynamic is suggestive but there are also clear differences. Luther’s stripped down version of Christianity was a radical change but it still provided people with a sturdy moral framework to guide their thinking and behaviour. Such foundational certainties are more elusive in our own time. On the other hand this very fact arguably provides a rationale for recovering, re-valuing and applying some of the universal human values outlined above. The latter are perhaps among the most viable sources of strength and continuity available during times of transformation and change.

The legitimacy of the Internet oligarchs is now in doubt from many quarters and for a variety of reasons, so limits and conditions are likely to be progressively imposed. Similarly, the business model that daily abuses countless human beings is unlikely to survive without major changes being wrought by newly enfranchised, democratically constituted cooperatives and civil authorities. While government actions may be slow and, at times uncertain, this study suggests that a host of responses, innovations and alternatives is under active development. It is inconceivable that these will not change the nature of digital engagement over time. So it is indeed possible to look ahead with qualified optimism and to anticipate a new and different renaissance. A renaissance that sets aside technological adventurism and wild, unconstrained innovation, in favour of positive human values and cultural traditions that balance human dignity and rights on the one hand with the enhanced stewardship of natural systems on the other.