1.7: Society and Groups

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 53276

Understanding Past and Current Societies

Society is defined as a population of people which shares the same geographic territory and culture. In sociology this typically refers to an entire country or community. Average people tend to use the word society differently than do sociologists. You might be thinking about the difference in the American Human Society (The Humane Society of the United States at http://www.hsus.org/ ); the American Cancer Society (at http://www.cancer.org/docroot/home/index.asp ); or the Society of Plastics Engineers (at www.4spe.org/ ) and US main stream society.

For sociologists a society is defined in terms of its functions. There are five:

- reproduction;

- sustenance;

- shelter;

- management of its membership;

- defense.

In the sociological definition of society, these three organizations listed above with their URL’s are not societies. They are Voluntary Organizations - formalized groups of individuals who work toward a common organizational (and often personal) set of goals. These voluntary organizations typically only concern themselves with 1 of the 5 functions—management of its membership.

There are three other types of organizations:

- Normative Organizations are organizations that people join because they perceive their goals as being socially or morally worthwhile (IE: Greenpeace);

- Coercive Organizations are organizations that people typically are forced into against their will (prison);

- Utilitarian Organizations are organizations that people typically join because of some tangible benefit which they expect to receive (Girl Scouts, PTA, or a political party).

All organizations exist in the structures of broader society.

Societies have been around for many thousands of years. Technological availability greatly influenced the size and durability of these societies. Rocks, sticks, spears, axes, bows and arrows, darts, plows, hand tools, dowels and nails, steam engines, electricity, factories, watches, computer chips, and other technological advances have greatly changed the nature of societies over these many years.

Early on, Hunting and Gathering Societies, those whose economies which are based on hunting animals and gathering vegetation, were very common throughout the history of the world. Eventually, Horticultural and Pastoral Societies, those characterized by domestication of animals and the use of hand tools to cultivate plants, developed and have also endured for centuries. In the last few centuries the Agricultural Society developed. Agricultural Societies utilize advanced technologies to support crops and livestock (plow) and in Western societies became the mainstay which enabled the Industrial Revolution to transpire by feeding society’s members.

Industrial Societies utilize machinery and energy sources (steam engine) rather than humans and animals for production. There was a time in the US when almost all the jobs were factory, production, or otherwise labor intensive jobs. Then came the computer chip which initiated

Postindustrial Societies, where societal production is based on creating, processing, and storing information. This is the modern society we live in today in the United States.Why Do Societies Change or Remain Stable?

As far back in Sociology’s history as its founder, Auguste Comte, Sociologists wanted to understand why societies changed or remained the same (Comte’s full name was Isidore Marie Auguste François Xavier Compte 17 January 1798-5 September 1857). Comte referred to Social Statics, or the study of social structure and how it influences social stability; and Social Dynamics, or the study of social structure and how it influences social change. A modern example of social statics might be the official governmental intervention of US economic recovery efforts; while social dynamics might be the new “government bailout” manipulation of the economy to establish economic security in volatile markets.

Emile Durkheim’s concept of Anomie focused on how daily norms (or the relative lack thereof) influenced the daily expectations and obligations of society’s members. In the village with an agricultural society, most people knew what everyone else did for a living and most shared in common similar daily life patterns.Mechanical Solidarity is a shared conscious among society's members who each has a similar form of livelihood. As industrialization emerged and transformed the rural communities while enlarging the urban-factory based, highly populated cities, norms became much more ambiguous. Durkheim called this Organic Solidarity, which is a sense of interdependence on the specializations of occupations in modern society. Those in larger cities had less daily regulated and organized patterns and could no longer provide the majority of their own needs—they became much more dependent on each other’s specializations. As Durkheim witnessed rapid social change that accompanied the Industrial Revolution, he attributed much of the personal challenge that came with it to Anomie and the difficult and often fuzzy normative regulation.

This brings us to an important and related issue—how a society functions and dysfunctions impacts the individual. Karl Marx argued the concept of Alienation, which is the resulting influence of industrialization on society’s members where they feel disconnected and powerless in the final direction of their destinies. To Marx, the social systems people created in turn controlled the pattern of their social life.

A later German Sociologist named Ferdinand Tönnies (1855-1936) wrote about two types of community experiences that were polar opposites. Gemeinschaft (Guh-mine-shoft) means "intimate community" and Gesellschaft (Guh-zell-shoft) means" impersonal associations." His observations, like Durkheim’s and Marx’s were based in the transition form rural to urban, agricultural to industrial, and small to large societies.

Gemeinschaft comes with a feeling of community togetherness and inter-relational mutual bonds where individuals and families are independent and for the most part self-sufficient. Whereas, Gesellschaft comes with a feeling of individuality in the context of large urban populations and a heavy dependence upon the specialties of others (mutual inter-dependence) to meet all one’s needs.

For people living in both large and smaller cities, there is a social connection they have with others called Social Cohesion - the degree to which members of a group or a society feel united by shared values and other social bonds. The study of social cohesion has become much more complex as societies have grown in number, diversity, and technological sophistry. Social Structure refers to the recurring patterns of behavior in society which people create through their interactions and relationships. Social structure of course can be literally considered (like the anatomy of a human body specifically defines parts and how they are related to one another) or figuratively considered where social institutions, laws, processes, and cultures shape the actions of we who live in these societies.

What Are Society’s Component Parts?

What are core parts of our social structure? The first and most important unit of measure in sociology is the Group, which is a set of two or more people who share common identity, interact regularly, and have shared expectations (roles), and function in their mutually agreed upon roles. Most people use the word, “group” differently from the sociological use. Non sociologists also use “group” differently from sociologists. They say group even if the cluster of people they are referring to don’t even know each other (like 6 people standing at the same bus stop). Sociologists use Aggregates, or the number of people in the same place at the same time. So people in the same movie theater, people at the same bus stop, and even people at a university football game are considered in aggregates, not groups.

The sociologists discuss categories. A Category is a number of people who share common characteristics. Brown-eyed people, people who wear hats, and people who vote independent are categories—they don’t necessarily share the same space, nor do they have shared expectations.

Figure 1. Photo of the Semi-Annual UVU Behavioral Science Poster Symposium

© 2007 Ron J. Hammond, Ph.D.

In the photo above, the professor on the left, Dr. Bret Breton posed for this photo with two of our undergraduate students. Twice a year we hold student research symposia where students present findings from their research studies. For 6 hours their posters are displayed and they answer questions and discuss their findings with any of the 26,000 students who attend Utah Valley University (a category of student). Throughout the day, clusters of students stand around tables (aggregates) while research team members (groups) teach passerby students what they did and what they learned while doing it.

Figure 2. Photo of the 2007 Winning AACS Student Problem Solving Competition

© 2007 Ron J. Hammond, Ph.DIn the photo above you can see the 2007 UVU student problem solving team (common identity) who competed in the 2007 Association of Applied and Clinical Sociology’s (See AACS at http://www.aacsnet.org/wp/?page_id=59 ) Student Problem Solving Competition. I’m with my wife (matching black T-shirts on the back left) and next to us on the left was a Social Worker we met while visiting the Ypsilanti, Michigan SOS Community Services headquarters. Trista (Pink blouse in the middle) was the student competition research team leader (specific role). She coordinated all the student team member’s efforts and created subcommittees with committee chairs who reported directly back to her (shared expectations).

The problem solving challenge faced by this group of students was to create a proposal which improved the employment opportunities of single mothers who came to SOS for help in finding jobs. You need to be aware that there were very difficult financial challenges facing these single mothers: the economy was severely depressed, the labor-intensive jobs had all but left the region, there were very few service jobs that fit the skill set of these mothers; and finally even the busses had stopped running because of fuel costs and other concerns. It was nearly impossible for a single mother to find a job! Since there are about 15,000 single mothers who come for help each year, this proposal took on a life of its own in terms of how important it would be. It transformed from a competition to a cause in the mind of my students.

This team met twice with SOS personnel; created inter-state networks between social service agencies in Utah, Michigan, and North Carolina; and held a banquet for local community service directors to brainstorm how they might approach a resolution to these issues. Many other efforts lead to a 3-pronged proposal which articulated specific strategies: first, the creation of a shuttle service where the SOS Community Center obtains a small fleet of shuttle vans which will be driven by the single mothers, exclusively for the single mothers who would pay a modest fare to get back and forth about town; second, the connection of the Sunshine Ladies Foundations Scholarship Program with the Washtenaw Community College—also in Ypsilanti (Google Doris Buffet’s charitable foundation WISP); and Third, the networking of the local Marriott resort to the SOS Community Services Agency.

Once the proposal was submitted, this group disbanded and focused their energies in other life pursuits. Their proposal did win the competition, but the experience in itself is considered more valuable because they feel liked they made a small difference for single mothers (and it enhanced their graduate school applications).

Why Are Groups Crucial to Society?

Groups come in varying sizes—Dyads are a group of two people and Triads are a group of three people. The number of people in a group plays an important structural role in the nature of the group’s functioning. Dyads are the simplest groups because 2 people have only 1 relationship between them. Triads have three relationships. A group of 4 has 6 relationships; 5 has 10; 6 has 15; 7 has 21; and one of my students from Brazil has 10 brothers and sisters and she counts 91 relationships just in her immediate family (not counting the brothers and sisters in law).

When triads form it looks much like a triangle and these typically take much more energy than dyads. A newly married couple experience great freedoms and opportunities to nurture their marital relationship. A triad forms when their first child is born, they experience a tremendous incursion upon their marital relationship from the child and the care demanded by the child—As Bill Cosby Said in his book “Fatherhood” “Children by their very nature are designed to ruin your marriage (see 1987, Doubleday Publisher, NY).”

Two of my Introduction to Sociology students told me a true story about how they were BFF’s since elementary school and had similar last names and even been in the same homerooms until they graduated high school. They then came to college together and majored in the same major. They told me and the other students in the class about what stressed their friendship when one fell in love and dated a young man.

The other felt a great deal of pressure to get along with her best friend’s boyfriend. She did and they all three were friends although each explained that the guy put more pressure on their own friendship. When the boyfriend-girlfriend relationship finally ended it put the other girl in an awkward position with the guy. They had established their own friendship, but since her best friend broke up with the guy she felt like she had to end her friendship with him too. She did.

You can begin to see how the Functional approach to studying groups gives you insight into how group structure, function, and dysfunction affect the everyday lives of group members. Sociometry is the study of groups and their structures (Google Jacob L. Moreno for its founder). To simply study it for the sake of creating more knowledge about it does not help groups directly. To solve problems you might be hired to come into an organization, examine the organization’s groups and functions or dysfunctions , then eventually create strategies for enhancing the quality of the groups’ interactions or expanding the groups social network in a beneficial way.

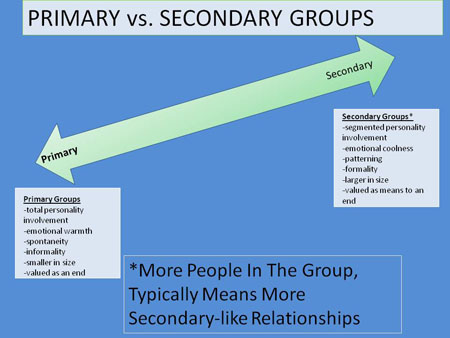

As sociologists further study the nature of the group’s relationships they realize that there are two broad types of groups: Primary Groups tend to be smaller, less formal, and more intimate (family and friends); whereas Secondary Groups tend to be larger, more formal, and much less personal (you and your doctor, mechanic, or accountant). Look at the diagram below. Typically with your primary groups, say with your roommates, you can be much more spontaneous and informal. On Friday night you can hang out where ever you want, change your plans as you want, and experience the fun as much as you want.

Contrast that to the relationship with your doctor. You have to call someone else to get an appointment, you have to wait if the doctor is behind, you typically call her or him “Doctor,” once the diagnoses and co-pay are made you leave and have to make another formal appointment if you need another visit. Your Introduction to Sociology class is most likely large and secondary. Your friends tend to be few and primary (see Figure 3 below).

With your friends, have you noticed that one or two tend to be informally in charge of the details? You might be the one who calls everyone and makes reservations or buys the tickets for the others. If so, you would have the informal role of “organizer.” Status is what you do in a role or otherwise stated, Status=is a socially defined position. There are three types of status considerations: Ascribed Status is present at birth (race, sex, or class); Achieved Status is attained through one's choices and efforts (college student, movie star, teacher, or athlete); and Master Status is a status which stands out above our other statuses and which distracts others from really seeing who we are.

Another consideration about groups and our roles in them is the fact that one single role can place a rather heavy burden on you (IE: student). Role Strain is the burden one feels within any given role. And when one role comes into direct conflict another or other roles you might experience Role Conflict, or the conflict and burdens one feels because the expectations of one role compete with the expectations of another role.