6.2: Lecture Content

- Page ID

- 23478

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Executive Power

Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution states “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” (55) With such vague phrasing, the term “executive power” can take on a number of meanings. Let’s discuss a few here.(1)

The Descriptive Model of Executive Powers

The traditional interpretation of executive power holds that it is a descriptive term at best, used only to summarize those enumerated powers listed in Article II. According to this view, all presidential power is defined in Article II and the executive or vesting clause does not add any power to the list.

Presidential examples of this model of governance come in the form of Dwight Eisenhower. Eisenhower’s nationalization of the Arkansas National Guard in 1957 came not from his proactive approach to desegregation in the South. Rather, Eisenhower’s leadership in this area stemmed from his literalist view of the Constitution that he “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed,” (55) with the law in this case being the Supreme Court’s ruling in (1) Brown V. Board of Education . (56)

The Conferral Model of Executive Power

The modern view of executive power is simply this: it confers power. Beyond descriptive measures, the conferral model of executive power not only embraces those enumerated powers outlined in Article II, but it likewise grants additional ones, also referred to as inherent powers. For instance, the Constitution makes no mention of executive privilege, executive agreements, or executive powers. However, the absence of such language has not prevented presidents from exercising such means, which have all been sanctioned by the U.S. Supreme Court. For instance, the Supreme Court’s ruling in (1) United States v. Nixon (1974) (58)sanctioned the president’s right to executive privilege; that is, the right of the president to protect confidential communications in the White House in the interest of national security. (1)

Models of Presidential Power

Historically speaking, the American presidency captures three models of presidential power: the Hamiltonian model, the Madisonian model, and the Jeffersonian ideology. As a general rule of thumb, nearly all presidents fall into one these models or perhaps, a combination. Thus, comprehension of all three models will prove to be quite useful in both assessing presidential leadership of a particular president, and identifying trends in the office of the presidency.

The Hamiltonian Model

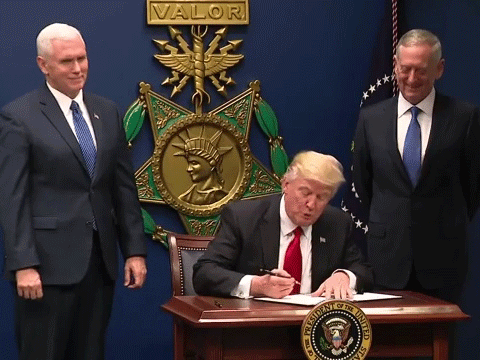

American politics dictates that the President of the United States is both head of state and head of government. Such designation serves as a marked distinction between the U.S. and other democracies abroad wherein these roles are divided between two separate individuals. Thus, with such vast responsibility, the Hamiltonian model holds that presidents must be resourceful in accomplishing his agenda vis-à-vis national interests. (57) This theory includes the promotion of inherent, executive powers to accomplish such goals. A contemporary example of this ideal can be summed up in President Trump’s delivery of Executive Order 13769 as an attempt to curtail illegal immigration in the U.S. Doing so served to fulfill a critical promise made on the campaign trail.

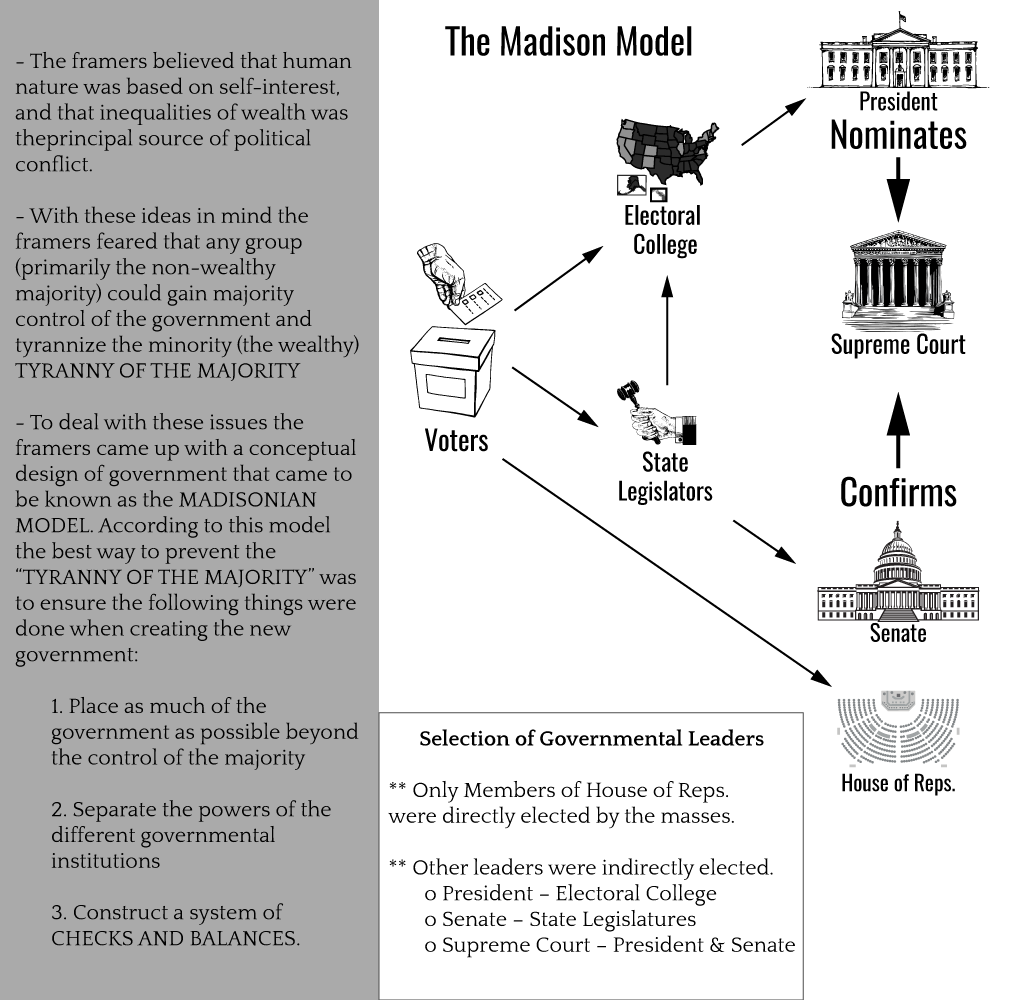

The Madisonian Model

A less creative model of the presidency can be found in the Madisonian model of leadership. Simply put, this standard rests on the principle of checks and balances, and, is, unarguably, the most traditional model of the presidency. (14) It emphasizes balanced powers and competing interests as checks against tyranny rule. George Washington, our first president, embodied this style of governance.

The Jeffersonian Model

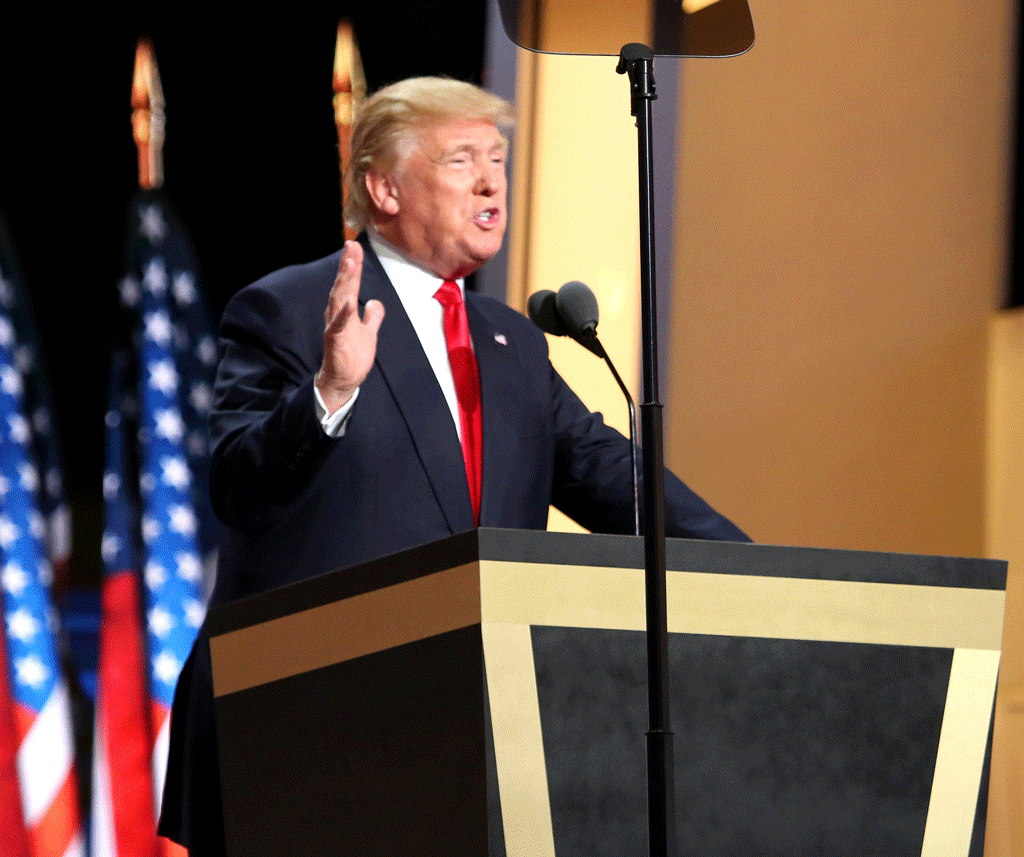

The Jeffersonian Model of the presidency gives way to increased democracy via the “will of the people, expressed through elections;” thus, advocating the benefit of political parties in American politics. (67) Now, while the Constitution is clear on the establishment of institutions and the election of public officials to government bodies, it is silent on how this process should come to fruition. Therefore, political parties aid in the development of such. Political parties, in particular America’s prevailing two-party system, delivers individuals to candidacy who, in turn, represent a segment of the American electorate who identify with the ideology behind the party label. In this way, political parties and the competition they spawn serve as an egalitarian impetus for deepening democracy. The president, as party leader of his respective coalition, aids in this process as parties seek to bring party platforms to national awareness. The 2016 Republican and Democratic National Conventions are demonstrative of the role political parties play in advancing the power of the presidency. (1)

Theories of Presidential Power at Work

With executive power and presidential models of leadership defined, let’s attempt to put these theories into practice by evaluating the historical executive orders below. While reviewing these orders, try to determine which model of the presidency (Hamiltonian, Madisonian, and Jeffersonian) is being exercised.

- Executive Order 9066, issued February 19, 1942 by President Franklin Roosevelt, which authorized the interment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

- Executive Order 9981, issued July 26, 1948 by President Harry Truman, which ended segregation in the U.S. Armed Forces.

- Executive Oder 10925, issued by President John F. Kennedy, which mandated the use of affirmative action and nondiscriminatory hiring practices by governmental agencies and contractors.

- Executive Order 13379, issued by President George W. Bush, which established the Office of Faith Based Initiatives and increased participation of religious organizations in federal social programs. (1)