3.1: Nature vs. Nurture

- Page ID

- 23752

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Developmental psychology seeks to understand the influence of genetics (nature) and environment (nurture) on human development.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

- Evaluate the reciprocal impacts between genes and the environment and the nature vs. nurture debate

KEY POINTS

-

- A significant issue in developmental psychology has been the relationship between the innateness of an attribute (whether it is part of our nature) and the environmental effects on that attribute (whether it is derived from or influenced by our environment, or nurture).

- Today, developmental psychologists rarely take polarized positions with regard to most aspects of development; instead, they investigate the relationship between innate and environmental influences.

- The biopsychosocial model states that biological, psychological, and social factors all play a significant role in human development.

- Environmental inputs can affect the expression of genes, a relationship called gene-environment interaction. An individual’s genes and their environment work together, communicating back and forth to create traits.

- The diathesis–stress model serves to explore how biological or genetic traits (diatheses) interact with environmental influences (stressors) to produce disorders, such as depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia.

TERMS

- genotypeThat part (DNA sequence) of the genetic makeup of a cell, and therefore of an organism or individual, which determines a specific characteristic (phenotype) of that cell/organism/individual.

- heritabilityThe ratio of the genetic variance of a population to its phenotypic variance; i.e., the proportion of variability that is genetic in origin.

- geneA unit of heredity; a segment of DNA or RNA that is transmitted from one generation to the next and carries genetic information such as the sequence of amino acids for a protein.

- traitAn identifying characteristic, habit, or trend.

- innateInborn; native; natural.

Developmental Psychology

Developmental psychology is the scientific study of changes that occur in human beings over the course of their lives. This field examines change and development across a broad range of topics, such as motor skills and other psycho-physiological processes; cognitive development involving areas like problem solving, moral and conceptual understanding; language acquisition; social, personality, and emotional development; and self-concept and identity formation. Developmental psychology explores the extent to which development is a result of gradual accumulation of knowledge or stage-like development, as well as the extent to which children are born with innate mental structures as opposed to learning through experience.

Nature Versus Nurture

A significant issue in developmental psychology is the relationship between the innateness of an attribute (whether it is part of our nature) and the environmental effects on that attribute (whether it is influenced by our environment, or nurture). This is often referred to as the nature vs. nurture debate, or nativism vs. empiricism.

- A nativist (“nature”) account of development would argue that the processes in question are innate and influenced by an organism’s genes. Natural human behavior is seen as the result of already-present biological factors, such as genetic code.

- An empiricist (“nurture”) perspective would argue that these processes are acquired through interaction with the environment. Nurtured human behavior is seen as the result of environmental interaction, which can provoke changes in brain structure and chemistry. For example, situations of extreme stress can cause problems like depression.

The nature vs. nurture debate seeks to understand how our personalities and traits are produced by our genetic makeup and biological factors, and how they are shaped by our environment, including our parents, peers, and culture. For instance, why do biological children sometimes act like their parents? Is it because of genetic similarity, or the result of the early childhood environment and what children learn from their parents?

Interaction of Genes and the Environment

Today, developmental psychologists rarely take such polarized positions (either/or) with regard to most aspects of development; instead, they investigate the relationship between innate and environmental influences (both/and). Developmental psychologists will often use the biopsychosocial model to frame their research: this model states that biological, psychological, and social (socio-economical, socio-environmental, and cultural) factors all play a significant role in human development.

We are all born with specific genetic traits inherited from our parents, such as eye color, height, and certain personality traits. Beyond our basic genotype, however, there is a deep interaction between our genes and our environment: our unique experiences in our environment influence whether and how particular traits are expressed, and at the same time, our genes influence how we interact with our environment (Diamond, 2009; Lobo, 2008). There is a reciprocal interaction between nature and nurture as they both shape who we become, but the debate continues as to the relative contributions of each.

Heritability refers to the origin of differences among people; it is a concept in biology that describes how much of the variation of a trait in a population is due to genetic differences in that population. Individual development, even of highly heritable traits such as eye color, depends not only on heritability but on a range of environmental factors, such as the other genes present in the organism and the temperature and oxygen levels during development. Environmental inputs can affect the expression of genes, a relationship called gene-environment interaction. Genes and the environment work together, communicating back and forth to create traits.

Some concrete behavioral traits are dependent upon one’s environment, home, or culture, such as the language one speaks, the religion one practices, and the political party one supports. However, some traits which reflect underlying talents and temperaments—such as how proficient at a language, how religious, or how liberal or conservative—can be partially heritable.

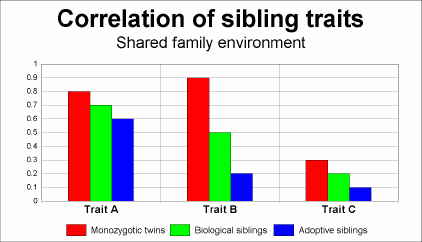

This chart illustrates three patterns one might see when studying the influence of genes and environment on individual traits. Each of these traits is measured and compared between monozygotic (identical) twins, biological siblings who are not twins, and adopted siblings who are not genetically related. Trait A shows a high sibling correlation but little heritability (illustrating the importance of environment). Trait B shows a high heritability, since the correlation of the trait rises sharply with the degree of genetic similarity. Trait C shows low heritability as well as low correlation generally, suggesting that the degree to which individuals display trait C has little to do with either genes or predictable environmental factors.

Heritability Estimates

This chart illustrates three patterns one might see when studying the influence of genes and environment on individual traits. Typically, monozygotic twins will have a high correlation of sibling traits, while biological siblings will have less in common, and adoptive siblings will have less than that. However, this can vary widely by trait.

Diathesis-Stress Model

The diathesis–stress model is a psychological theory that attempts to explain behavior as a predispositional vulnerability together with stress from life experiences. The term diathesis derives from the Greek term for disposition, or vulnerability, and it can take the form of genetic, psychological, biological, or situational factors. The diathesis, or predisposition, interacts with the subsequent stress response of an individual. Stress refers to a life event or series of events that disrupt a person’s psychological equilibrium and potentially serve as a catalyst to the development of a disorder. Thus, the diathesis–stress model serves to explore how biological or genetic traits (diatheses) interact with environmental influences (stressors) to produce disorders, such as depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia.