16.4: Psychosocial Development

- Page ID

- 23838

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Gaining Adult Status

Many of the developmental tasks of early adulthood involve becoming part of the adult world and gaining independence. Young adults sometimes complain that they are not treated with respect-especially if they are put in positions of authority over older workers. Consequently, young adults may emphasize their age to gain credibility from those who are even slightly younger. “You’re only 23? I’m 27!” a young adult might exclaim. (Note: This kind of statement is much less likely to come from someone in their 40s!).

The focus of early adulthood is often on the future. Many aspects of life are on hold while people go to school, go to work, and prepare for a brighter future. There may be a belief that the hurried life now lived will improve ‘as soon as I finish school’ or ‘as soon as I get promoted’ or ‘as soon as the children get a little older.’ As a result, time may seem to pass rather quickly. The day consists of meeting many demands that these tasks bring. The incentive for working so hard is that it will all result in better future.

Levinson’s Theory

In 1978, Daniel Levinson published a book entitled The Seasons of a Man’s Life in which he presented a theory of development in adulthood. Levinson’s work was based on in-depth interviews with 40 men between the ages of 35-45. He later conducted interviews with women as well (1996). According to Levinson, these adults have an image of the future that motivates them. This image is called “the dream” and for the men interviewed, it was a dream of how their career paths would progress and where they would be at midlife. Women held a “split dream”; an image of the future in both work and family life and a concern with the timing and coordination of the two. Dreams are very motivating. Dreams of a home bring excitement to couples as they look, save, and fantasize about how life will be. Dreams of careers motivate students to continue in school as they fantasize about how much their hard work will pay off. Dreams of playgrounds on a summer day inspire would be parents. A dream is perfect and retains that perfection as long as it remains in the future. But as the realization of it moves closer, it may or may not measure up to its image. If it does, all is well. But if it does not, the image must be replaced or modified. And so, in adulthood, plans are made, efforts follow, and plans are reevaluated. This creating and recreating characterizes Levinson’s theory.

Levinson’s stages are presented below (Levinson, 1978). He suggests that period of transition last about 5 years and periods of “settling down” last about 7 years. The ages presented below are based on life in the middle class about 30 years ago. Think about how these ages and transitions might be different today.

- Early adult transition (17-22): Leaving home, leaving family; making first choices about career and education

- Entering the adult world (22-28): Committing to an occupation, defining goals, finding intimate relationships

- Age 30 transition (28-33): Reevaluating those choices and perhaps making modifications or changing one’s attitude toward love and work

- Settling down (33 to 40): Reinvesting in work and family commitments; becoming involved in the community

- Midlife transition (40-45): Reevaluating previous commitments; making dramatic changes if necessary; giving expression to previously ignored talents or aspirations; feeling more of a sense of urgency about life and its meaning

- Entering middle adulthood (45-50): Committing to new choices made and placing one’s energies into these commitments

Adulthood, then, is a period of building and rebuilding one’s life. Many of the decisions that are made in early adulthood are made before a person has had enough experience to really understand the consequences of such decisions. And, perhaps, many of these initial decisions are made with one goal in mind-to be seen as an adult. As a result, early decisions may be driven more by the expectations of others. For example, imagine someone who chose a career path based on other’s advice but now find that the job is not what was expected. The age 30 transition may involve recommitting to the same job, not because it’s stimulating, but because it pays well. Settling down may involve settling down with a new set of expectations for that job. As the adult gains status, he or she may be freer to make more independent choices. And sometimes these are very different from those previously made. The midlife transition differs from the age 30 transition in that the person is more aware of how much time has gone by and how much time is left. This brings a sense of urgency and impatience about making changes. The future focus of early adulthood gives way to an emphasis on the present in midlife. (We will explore this in our next lesson.) Overall, Levinson calls our attention to the dynamic nature of adulthood.

Exercise

How well do you think Levinson’s theory translates culturally? Do you think that personal desire and a concern with reconciling dreams with the realities of work and family is equally important in all cultures? Do you think these considerations are equally important in all social classes, races and ethnic groups? Why or why not? How might this model be modified in today’s economy?

Erikson’s Theory

Intimacy vs. Isolation

Erikson believed that the main task of early adulthood was to establish intimate relationships. Intimate relationships are more difficult if one is still struggling with identity. Achieving a sense of identity is a life-long process, but there are periods of identity crisis and stability. And having some sense of identify is essential for intimate relationships. In early adulthood, intimacy (or emotional or psychological closeness) comes from friendships and mates.

Friendships as a source of intimacy

In our twenties, intimacy needs may be met in friendships rather than with partners. This is especially true in the United States today as many young adults postpone making long-term commitments to partners either in marriage or in cohabitation. The kinds of friendships shared by women tend to differ from those shared by men (Tannen, 1990). Friendships between men are more likely to involve sharing information, providing solutions, or focusing on activities rather than discussion problems or emotions. Men tend to discuss opinions or factual information or spend time together in an activity of mutual interest. Friendships between women are more likely to focus on sharing weaknesses, emotions, or problems. Women talk about difficulties they are having in other relationships and express their sadness, frustrations, and joys. These differences in approaches lead to problems when men and women come together. She may want to vent about a problem she is having; he may want to provide a solution and move on to some activity. But when he offers a solution, she thinks he does not care!

Friendships between men and women become more difficult because of the unspoken question about whether the friendships will lead to a romantic involvement. It may be acceptable to have opposite-sex friends as an adolescent, but once a person begins dating or marries; such friendships can be considered threatening. Consequently, friendships may diminish once a person has a partner or single friends may be replaced with couple friends.

Partners as a source of intimacy: Dating, Cohabitation, and Mate Selection

Dating

In general, traditional dating among teens and those in their early twenties has been replaced with more varied and flexible ways of getting together. The Friday night date with dinner and a movie that may still be enjoyed by those in their 30s gives way to less formal, more spontaneous meetings that may include several couples or a group of friends. Two people may get to know each other and go somewhere alone. How would you describe a “typical” date? Who calls? Who pays? Who decides where to go? What is the purpose of the date? In general, greater planning is required for people who have additional family and work responsibilities. Teens may simply have to negotiate getting out of the house and carving out time to be with friends.

Cohabitation or Living Together

How prevalent is cohabitation? There are over 5 million heterosexual cohabiting couples in the United States and, an additional 594,000 same-sex couples share households (U. S. Census Bureau, 2006). In 2000, 9 percent of women and 12 percent of men were in cohabiting relationships (Bumpass in Casper & Bianchi, 2002). This number reflects only those couples who were together when census data were collected, however. The number of cohabiting couples in the United States today is over 10 times higher than it was in 1960.

Similar increases have also occurred in other industrialized countries. For example, rates are high in Great Britain, Australia, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. In fact, more children in Sweden are born to cohabiting couples than to married couples. The lowest rates of cohabitation are in Ireland, Italy, and Japan (Benokraitis, 2005).

How long do cohabiting relationships last?

Cohabitation tends to last longer in European countries than in the United States. Half of cohabiting relationships in the U. S. end within a year; only 10 percent last more than 5 years. These short-term cohabiting relationships are more characteristics of people in their early 20s. Many of these couples eventually marry. Those who cohabit more than five years tend to be older and more committed to the relationship. Cohabitation may be preferable to marriage for a number of reasons. For partners over 65, cohabitation is preferable to marriage for practical reasons. For many of them, marriage would result in a loss of Social Security benefits and consequently is not an option. Others may believe that their relationship is more satisfying because they are not bound by marriage. Consider this explanation from a 62-year old woman who was previously in a long-term, dissatisfying marriage. She and her partner live in New York but spend winters in South Texas at a travel park near the beach. “There are about 20 other couples in this park and we are the only ones who aren’t married. They look at us and say, ‘I wish we were so in love’. I don’t want to be like them.” (Author’s files.) Or another couple who have been happily cohabiting for over 12 years. Both had previously been in bad marriages that began as long-term, friendly, and satisfying relationships. But after marriage, these relationships became troubled marriages. These happily cohabiting partners stated that they believe that there is something about marriage that “ruins a friendship”.

The majority of people who cohabit are between the ages of 25-44. Only about 20 percent of those who cohabit are under age 24. Cohabitation among younger adults tends to be short-lived. Relationships between older adults tend to last longer.

Why do people cohabit?

People cohabit for a variety of reasons. The largest number of couples in the United States engages in premarital cohabitation. These couples are testing the relationship before deciding to marry. About half of these couples eventually get married. The second most common type of cohabitation is dating cohabitation. These partnerships are entered into for fun or convenience and involve less commitment than premarital cohabitation. About half of these partners break up and about one-third eventually marry. Trial marriage is a type of cohabitation in which partners are trying to see what it might be like to be married. They are not testing the other person as a potential mate, necessarily; rather, they are trying to find out how being married might feel and what kinds of adjustments they might have to make. Over half of these couples split up. In the substitute marriage, partners are committed to one another and are not necessarily seeking marriage. Forty percent of these couples continue to cohabit after 5 to 7 years (Bianchi & Casper, 2000). Certainly, there are other reasons people cohabit. Some cohabit out of a feeling of insecurity or to gain freedom from someone else (Ridley, C. Peterman, D. & Avery, A., 1978). And many cohabit because they cannot legally marry.

Same-Sex Couples

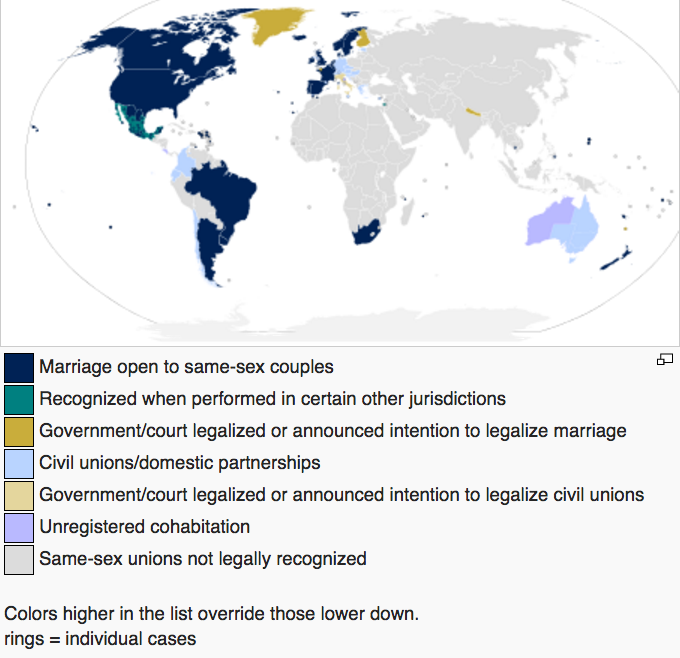

Same sex marriage is legal in 21 countries, including the United States. Many other countries either recognize same-sex couples for the purpose of immigration, grant rights for domestic partnerships, or grant common law marriage status to same-sex couples.

Same sex marriage is legal in 21 countries, including the United States. Many other countries either recognize same-sex couples for the purpose of immigration, grant rights for domestic partnerships, or grant common law marriage status to same-sex couples.

Same sex couples struggle with concerns such as the division of household tasks, finances, sex, and friendships as do heterosexual couples. One difference between same sex and heterosexual couples, however, is that same sex couples have to live with the added stress that comes from social disapproval and discrimination. And continued contact with an ex-partner may be more likely among homosexuals and bisexuals because of closeness of the circle of friends and acquaintances.

Mate-Selection

Contemporary young adults in the United States are waiting longer than before to marry. The median age of first marriage is 25 for women and 27 for men. This reflects a dramatic increase in age of first marriage for women, but the age for men is similar to that found in the late 1800s. Marriage is being postponed for college and starting a family often takes place after a woman has completed her education and begun a career. However, the majority of women will eventually marry (Bianchi & Casper, 2000).

Social exchange theory suggests that people try to maximize rewards and minimize costs in social relationships. Each person entering the marriage market comes equipped with assets and liabilities or a certain amount of social currency with which to attract a prospective mate. For men, assets might include earning potential and status while for women, assets might include physical attractiveness and youth.

A fair exchange

Customers in the market do not look for a ‘good deal’, however. Rather, most look for a relationship that is mutually beneficial or equitable. One of the reasons for this is because most a relationship in which one partner has far more assets than the other will result if power disparities and a difference in the level of commitment from each partner. According to Waller’s principle of least interest, the partner who has the most to lose without the relationship (or is the most dependent on the relationship) will have the least amount of power and is in danger of being exploited. A greater balance of power, then, may add stability to the relationship.

Homogamy and the filter theory of mate selection: Societies specify through both formal and informal rules who is an appropriate mate. Consequently, mate selection is not completely left to the individual. Rules of endogamy indicate within which groups we should marry. For example, many cultures specify that people marry within their own race, social class, age group, or religion. These rules encourage homogamy or marriage between people who share social characteristics. The majority of marriages in the U. S. are homogamous with respect to race, social class, age and to a lesser extent, religion. Rules of exogamy specify the groups into which one is prohibited from marrying. For example, in most of the United States, people are not allowed to marry someone of the same sex.

According to the filter theory of mate selection (Kerckhoff & Davis, 1962), the pool of eligible partners becomes narrower as it passes through filters used to eliminate members of the pool. One such filter is propinquity or geographic proximity. Mate selection in the United States typically involves meeting eligible partners face to face. Those with whom one does not come into contact are simply not contenders. Race and ethnicity is another filter used to eliminate partners. Although interracial dating has increased in recent years and interracial marriage rates are higher than before, interracial marriage still represents only 5.4 percent of all marriages in the United States. Physical appearance is another feature considered when selecting a mate. Age, social class, and religion are also criteria used to narrow the field of eligibles. Thus, the field of eligibles becomes significantly smaller before those things we are most conscious of such as preferences, values, goals, and interests, are even considered.

Online Relationships

What impact does the internet have on the pool of eligibles? There are hundreds of websites designed to help people meet. Some of these are geared toward helping people find suitable marriage partners and others focus on less committed involvements. Websites focus on specific populations-big beautiful women, Christian motorcyclists, parents without partners, and people over 50, etc. Theoretically, the pool of eligibles is much larger as a result. However, many who visit sites are not interested in marriage; many are already married. And so if a person is looking for a partner online, the pool must be filtered again to eliminate those who are not seeking long-term relationships. While this is true in the traditional marriage market as well, knowing a person’s intentions and determining the sincerity of their responses becomes problematic online.

This young man offers his picture and a description of his professional status and stability. While he’s looking for employment, his ad might also help him find an eligible partner online.

Online communication differs from face-to-face interaction in a number of ways. In face-to-face meetings, people have many cues upon which to base their first impressions. A person’s looks, voice, mannerisms, dress, scent, and surroundings all provide information in face-to-face meetings. But in computer- mediated meetings, written messages are the only cues provided. Fantasy is used to conjure up images of voice, physical appearance, mannerisms, and so forth. The anonymity of online involvement makes it easier to become intimate without fear of interdependence. It is easier to tell one’s secrets because there is little fear of loss. One can find a virtual partner who is warm, accepting, and undemanding (Gwinnell, 1998). And exchanges can be focused more on emotional attraction than physical appearance.

When online, people tend to disclose more intimate details about themselves more quickly. A shy person can open up without worrying about whether or not the partner is frowning or looking away. And someone who has been abused may feel safer in virtual relationships. None of the worries of home or work get in the way of the exchange. The partner can be given one’s undivided attention, unlike trying to have a conversation on the phone with a houseful of others or at work between duties. Online exchanges take the place of the corner café as a place to relax, have fun, and be you (Brooks, 1997). However, breaking up or disappearing is also easier. A person can simply not respond, or block e-mail.

But what happens if the partners meet face to face? People often complain that pictures they have been provided of the partner are misleading. And once couples begin to think more seriously about the relationship, the reality of family situations, work demands, goals, timing, values, and money all add new dimensions to the mix. Next we will turn our attention to theories of love.