3.3: Three Types of Audience Analysis

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 161028

- Brooke-Ashley Lipson Pool

- California Polytechnic State University

Learning Objectives

- Understand how to gather and use demographic information.

- Understand how to gather and use psychographic information.

- Understand how to gather and use situational information.

While audience analysis does not guarantee against errors in judgment, it will help you make good choices in topic, language, style of presentation, and other aspects of your speech. The more you know about your audience, the better you can serve their interests and needs. There are certainly limits to what we can learn through information collection, and we need to acknowledge that before making assumptions, but knowing how to gather and use information through audience analysis is an essential skill for successful speakers.

Demographic Analysis

As indicated earlier, demographic information includes factors such as gender, age range, marital status, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. In your public speaking class, you probably already know how many students are male and female, their approximate ages, and so forth. But how can you assess the demographics of an audience ahead of time if you have had no previous contact with them? In many cases, you can ask the person or organization that has invited you to speak; it’s likely that they can tell you a lot about the demographics of the people who are expected to come to hear you.

Whatever method you use to gather demographics, exercise respect from the outset. For instance, if you are collecting information about whether audience members have ever been divorced, be aware that not everyone will want to answer your questions. You can’t require them to do so, and you may not make assumptions about their reluctance to discuss the topic. You must allow them their privacy.

Age

There are certain things you can learn about an audience based on age. For instance, if your audience members are first-year college students, you can assume that they have grown up in the post-9/11 era and have limited memory of what life was like before the “war on terror.” If your audience includes people in their forties and fifties, it is likely they remember a time when people feared they would contract the AIDS virus from shaking hands or using a public restroom. People who are in their sixties today came of age during the 1960s, the era of the Vietnam War and a time of social confrontation and experimentation. They also have frames of reference that contribute to the way they think, but it may not be easy to predict which side of the issues they support.

Gender

Gender can define human experience. Clearly, most women have had a different cultural experience from that of men within the same culture. Some women have found themselves excluded from certain careers. Some men have found themselves blamed for the limitations imposed on women. In books such as You Just Don’t Understand and Talking from 9 to 5, linguist Deborah Tannen has written extensively on differences between men’s and women’s communication styles. Tannen explains, “This is not to say that all women and all men, or all boys and girls, behave any one way. Many factors influence our styles, including regional and ethnic backgrounds, family experience and individual personality. But gender is a key factor, and understanding its influence can help clarify what happens when we talk” (Tannen, 1994).

Marriage tends to impose additional roles on both men and women and divorce even more so, especially if there are children. Even if your audience consists of young adults who have not yet made occupational or marital commitments, they are still aware that gender and the choices they make about issues such as careers and relationships will influence their experience as adults.

Culture

In past generations, Americans often used the metaphor of a “melting pot” to symbolize the assimilation of immigrants from various countries and cultures into a unified, harmonious “American people.” Today, we are aware of the limitations in that metaphor, and have largely replaced it with a multiculturalist view that describes the American fabric as a “patchwork” or a “mosaic.” We know that people who immigrate do not abandon their cultures of origin in order to conform to a standard American identity. In fact, cultural continuity is now viewed as a healthy source of identity.

We also know that subcultures and cocultures exist within and alongside larger cultural groups. For example, while we are aware that Native American people do not all embrace the same values, beliefs, and customs as mainstream white Americans, we also know that members of the Navajo nation have different values, beliefs, and customs from those of members of the Sioux or the Seneca. We know that African American people in urban centers like Detroit and Boston do not share the same cultural experiences as those living in rural Mississippi. Similarly, white Americans in San Francisco may be culturally rooted in the narrative of distant ancestors from Scotland, Italy, or Sweden or in the experience of having emigrated much more recently from Australia, Croatia, or Poland.

Not all cultural membership is visibly obvious. For example, people in German American and Italian American families have widely different sets of values and practices, yet others may not be able to differentiate members of these groups. Differences are what make each group interesting and are important sources of knowledge, perspectives, and creativity.

Religion

There is wide variability in religion as well. The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life found in a nationwide survey that 84 percent of Americans identify with at least one of a dozen major religions, including Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism, Islam, Hinduism, and others. Within Christianity alone, there are half a dozen categories including Roman Catholic, Mormon, Jehovah’s Witness, Orthodox (Greek and Russian), and a variety of Protestant denominations. Another 6 percent said they were unaffiliated but religious, meaning that only one American in ten is atheist, agnostic, or “nothing in particular” (Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, 2008).

Even within a given denomination, a great deal of diversity can be found. For instance, among Roman Catholics alone, there are people who are devoutly religious, people who self-identify as Catholic but do not attend mass or engage in other religious practices, and others who faithfully make confession and attend mass but who openly question Papal doctrine on various issues. Catholicism among immigrants from the Caribbean and Brazil is often blended with indigenous religion or with religion imported from the west coast of Africa. It is very different from Catholicism in the Vatican.

The dimensions of diversity in the religion demographic are almost endless, and they are not limited by denomination. Imagine conducting an audience analysis of people belonging to an individual congregation rather than a denomination: even there, you will most likely find a multitude of variations that involve how one was brought up, adoption of a faith system as an adult, how strictly one observes religious practices, and so on.

Yet, even with these multiple facets, religion is still a meaningful demographic lens. It can be an indicator of probable patterns in family relationships, family size, and moral attitudes.

Group Membership

In your classroom audience alone, there will be students from a variety of academic majors. Every major has its own set of values, goals, principles, and codes of ethics. A political science student preparing for law school might seem to have little in common with a student of music therapy, for instance. In addition, there are other group memberships that influence how audience members understand the world. Fraternities and sororities, sports teams, campus organizations, political parties, volunteerism, and cultural communities all provide people with ways of understanding the world as it is and as we think it should be.

Because public speaking audiences are very often members of one group or another, group membership is a useful and often easy to access facet of audience analysis. The more you know about the associations of your audience members, the better prepared you will be to tailor your speech to their interests, expectations, and needs.

Education

Education is expensive, and people pursue education for many reasons. Some people seek to become educated, while others seek to earn professional credentials. Both are important motivations. If you know the education levels attained by members of your audience, you might not know their motivations, but you will know to what extent they could somehow afford the money for an education, afford the time to get an education, and survive educational demands successfully.

The kind of education is also important. For instance, an airplane mechanic undergoes a very different kind of education and training from that of an accountant or a software engineer. This means that not only the attained level of education but also the particular field is important in your understanding of your audience.

Occupation

People choose occupations for reasons of motivation and interest, but their occupations also influence their perceptions and their interests. There are many misconceptions about most occupations. For instance, many people believe that teachers work an eight-hour day and have summers off. When you ask teachers, however, you might be surprised to find out that they take work home with them for evenings and weekends, and during the summer, they may teach summer school as well as taking courses in order to keep up with new developments in their fields. But even if you don’t know those things, you would still know that teachers have had rigorous generalized and specialized qualifying education, that they have a complex set of responsibilities in the classroom and the institution, and that, to some extent, they have chosen a relatively low-paying occupation over such fields as law, advertising, media, fine and performing arts, or medicine. If your audience includes doctors and nurses, you know that you are speaking to people with differing but important philosophies of health and illness. Learning about those occupational realities is important in avoiding wrong assumptions and stereotypes. We insist that you not assume that nurses are merely doctors “lite.” Their skills, concerns, and responsibilities are almost entirely different, and both are crucially necessary to effective health care.

Psychographic Analysis

Whereas demographic characteristics describe the “facts” about the people in your audience and are focused on the external, psychographic characteristics explain the inner qualities. Although there are many ways to think about this topic, here the ones relevant to a speech will be explored: beliefs, attitudes, needs, and values.

Beliefs

Daryl Bem (1970) defined beliefs as “statements we hold to be true.” Notice this definition does not say the beliefs are true, only that we hold them to be true and as such they determine how we respond to the world around us. Stereotypes are a kind of belief: we believe all the people in a certain group are “like that” or share a trait. Beliefs are not confined to the religious realm but touch all aspects of our experience. Sports fans believe certain things about their favorite teams. Republicans and Democrats believe certain, usually different, principles about how the government should be run.

Beliefs, according to Bem, come essentially from our experience and from sources we trust.For example, a person may believe everyone should take public speaking because in their own experience the course helped them be successful in college and a career. Another person may believe that corporal punishment is good for children because their own parents–whom they love and trust–spanked them after their misbehavior.

Therefore, beliefs are hard to change—not impossible, just difficult. Beliefs are harder to change based on their level of each of these characteristics of belief:

- stability—the longer we hold them, the more stable or entrenched they are;

- centrality—they are in the middle of our identity, self-concept, or “who we are”;

- saliency—we think about them a great deal; and

- strength—we have a great deal of intellectual or experiential support for the belief or we engage in activities that strengthen the beliefs.

Beliefs can have varying levels of stability, centrality, salience, and strength. An educator’s beliefs about the educational process and importance of education would be strong (support from everyday experience and reading sources of information), central (how he makes his living and defines his work), salient (he spends every day thinking about it), and stable (especially if he has been an educator a long time). Beliefs can be changed, and we will examine how in Chapter 13 under persuasion, but it is not a quick process.

Attitudes

The next psychographic characteristic, attitude, is sometimes a direct effect of belief. Attitude is defined as a stable positive or negative response to a person, idea, object, or policy (Bem 1970). More specifically, Myers (2012) defines it as “a favorable or unfavorable evaluative reaction toward someone or something, exhibited in one’s beliefs, feelings, or intended behavior” (p. 36). How do you respond when you hear the name of a certain singer, movie star, political leader, sports team, or law in your state? Your response will be either positive or negative, or maybe neutral if you are not familiar with the object of the attitude. Where did that attitude come from? Psychologists and communication scholars study attitude formation and change probably as much as any other subject, and have found that attitude comes from experiences, peer groups, beliefs, rewards, and punishments.

Do not confuse attitude with “mood.” Attitudes are stable; if you respond negatively to Brussels sprouts today, you probably will a week from now. That does not mean they are unchangeable, only that, like beliefs, they change slowly and in response to certain experiences, information, or strategies. As with beliefs, we will examine how to change attitudes in the chapter on persuasion. Changing attitudes is a primary task of public speakers because attitudes are the most determining factor in what people actually do. In other words, attitudes lead to actions, and interestingly, actions leads to and strengthen attitudes. Think back to the TedTalk video by Dr. Amy Cuddy that you watched in Chapter 1. She explains that acting powerful and confident can strengthen your attitude of confidence.

We may hold a belief that regular daily exercise is a healthy activity, but that does not mean we will have a positive attitude toward it. There may be other attitudes that compete with the belief, such as “I do not like to sweat,” or “I don’t like exercising alone.” Also, we may not act upon a belief because we do not feel there is a direct, immediate benefit from it or we may not believe we have time right now in college. If we have a positive attitude toward exercise, we will more likely engage in it than if we only believe it is generally healthy

Values

As you can see, attitude and belief are somewhat complex “constructs,” but fortunately the next two are more straightforward. (A construct is “a tool used in psychology to facilitate understanding of human behavior; a label for a cluster of related but co-varying behaviors” [Rogelberg, 2007].) Values are goals we strive for and what we consider important and desirable. However, values are not just basic wants. A person may want a vintage sports car from the 1960s, and may value it because of the amount of money it costs, but the vintage sports car is not a value; it represents a value of either

- nostalgia (the person’s parents owned one in the 1960s and it reminds him of good times),

- display (the person wants to show it off and get “oohs” and “ahs”),

- materialism (the person believes the adage that the one who dies with the most toys wins),

- aesthetics and beauty (the person admires the look of the car and enjoys maintaining the sleek appearance),

- prestige (the person has earned enough money to enjoy and show off this kind of vehicle), or

- physical pleasure (the driver likes the feel of driving a sports car on the open road).

Therefore we can engage in the same behavior but for different values; one person may participate in a river cleanup because she values the future of the planet; another may value the appearance of the community in which she lives; another just because friends are involved and she values relationships. A few years ago political pundits coined the term “values voters,” usually referring to social conservatives, but this is a misnomer because almost everyone votes and otherwise acts upon their values—what is important to the individual.

Needs

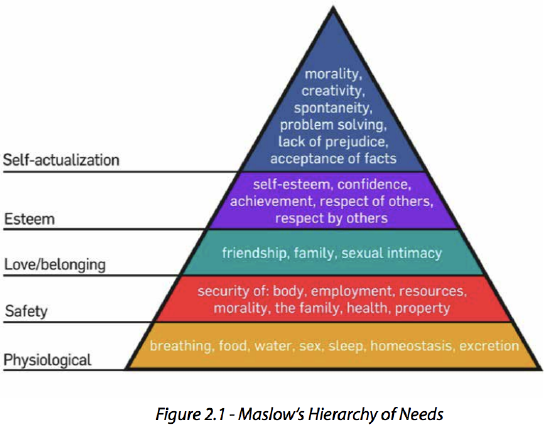

The fourth psychographic characteristic is needs, which are important deficiencies that we are motivated to fulfill. You may already be familiar with the well-known diagram known as Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs (Maslow, 1943). It is commonly discussed in the fields of management, psychology, and health professions. A version of it is shown in Figure 2.1. Some recent versions show it with 8 levels.) It is one way to think about needs. In trying to understand human motivation, Maslow theorized that as our needs represented at the base of the pyramid are fulfilled, we move up the hierarchy to fulfill other types of need (McLeod, 2014).

According to Maslow’s theory, our most basic physiological or survival needs must be met before we move to the second level, which is safety and security. When our needs for safety and security are met, we move up to relationship or connection needs, often called “love and belongingness.” The fourth level up is esteem needs, which could be thought of as achievement, accomplishment, or self-confidence. The highest level, self-actualization, is achieved by those who are satisfied and secure enough in the lower four that they can make sacrifices for others. Self-actualized persons are usually thought of as altruistic or charitable. Maslow also believed that studying motivation was best done by understanding psychologically healthy individuals, and he also used child development to construct his model. (Maslow is not without his critics; see Neher, 1991).

In another course you might go into more depth about Maslow’s philosophy and theory, but the key point to remember here is that your audience members are experiencing both “felt” and “real” needs. They may not even be aware of their needs. In a persuasive speech one of your tasks is to show the audience that needs exist that they might not know about. For example, gasoline sold in most of the U.S. has ethanol, a plant-based product, added to it, usually about 10%. Is this beneficial or detrimental for the planet, the engine of the car, or consumers’ wallets? Your audience may not even be aware of the ethanol, its benefits, and the problems it can cause.

A “felt” need is another way to think about strong “wants” that the person believes will fulfill or satisfy them even if the item is not necessary for survival. For example, one humorous depiction of the Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (seen on Facebook) has the words “wifi” scribbled at the bottom of the pyramid. Another meme has “coffee” scribbled at the bottom of the hierarchy. As great as wifi and coffee are, they are not crucial to human survival, either individually or collectively, but we do want them so strongly that they operate like needs.

So, how do these psychographic characteristics operate in preparing a speech? They are most applicable to a persuasive speech, but they do apply to other types of speeches as well. What are your audience’s informational needs? What beliefs or attitudes do they have that could influence your choice of topic, sources, or examples? How can you make them interested in the speech by appealing to their values? The classroom speeches you give will allow you a place to practice audience analysis based on demographic and psychographic characteristics, and that practice will aid you in future presentations in the work place and community.

This page titled 2.1: Psychographic Characteristics is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Kris Barton & Barbara G. Tucker (GALILEO Open Learning Materials)

Preexisting Notions about Your Topic

Many things are a great deal more complex than we realize. Media stereotypes often contribute to our oversimplifications. For instance, one of your authors, teaching public speaking in the past decade, was surprised to hear a student claim that “the hippies meant well, but they did it wrong.” Aside from the question of the “it” that was done wrong, there was a question about how little the student actually knew about the diverse hippy cultures and their aspirations. The student seemed unaware that some of “the hippies” were the forebears of such things as organic bakeries, natural food co-ops, urban gardens, recycling, alternative energy, wellness, and other arguably positive developments.

It’s important to know your audience in order to make a rational judgment about how their views of your topic might be shaped. In speaking to an audience that might have differing definitions, you should take care to define your terms in a clear, honest way.

At the opposite end from oversimplification is the level of sophistication your audience might embody. Your audience analysis should include factors that reveal it. Suppose you are speaking about trends in civil rights in the United States. You cannot pretend that advancement of civil rights is virtually complete nor can you claim that no progress has been made. It is likely that in a college classroom, the audience will know that although much progress has been made, there are still pockets of prejudice, discrimination, and violence. When you speak to an audience that is cognitively complex, your strategy must be different from one you would use for an audience that is less educated in the topic. With a cognitively complex audience, you must acknowledge the overall complexity while stating that your focus will be on only one dimension. With an audience that’s uninformed about your topic, that strategy in a persuasive speech could confuse them; they might well prefer a black-and-white message with no gray areas. You must decide whether it is ethical to represent your topic this way.

When you prepare to do your audience analysis, include questions that reveal how much your audience already knows about your topic. Try to ascertain the existence of stereotyped, oversimplified, or prejudiced attitudes about it. This could make a difference in your choice of topic or in your approach to the audience and topic.

Preexisting Notions about You

People form opinions readily. For instance, we know that students form impressions of teachers the moment they walk into our classrooms on the first day. You get an immediate impression of our age, competence, and attitude simply from our appearance and nonverbal behavior. In addition, many have heard other students say what they think of us.

The same is almost certainly true of you. But it’s not always easy to get others to be honest about their impressions of you. They’re likely to tell you what they think you want to hear. Sometimes, however, you do know what others think. They might think of you as a jock, a suit-wearing conservative, a nature lover, and so on. Based on these impressions, your audience might expect a boring speech, a shallow speech, a sermon, and so on. However, your concern should still be serving your audience’s needs and interests, not debunking their opinions of you or managing your image. In order to help them be receptive, you address their interests directly, and make sure they get an interesting, ethical speech.

Situational Analysis

The next type of analysis is called the situational audience analysis because it focuses on characteristics related to the specific speaking situation. The situational audience analysis can be divided into two main questions:

- How many people came to hear my speech and why are they here? What events, concerns, and needs motivated them to come? What is their interest level, and what else might be competing for their attention?

- What is the physical environment of the speaking situation? What is the size of the audience, layout of the room, existence of a podium or a microphone, and availability of digital media for visual aids? Are there any distractions, such as traffic noise?

Audience Size

In a typical class, your audience is likely to consist of twenty to thirty listeners. This audience size gives you the latitude to be relatively informal within the bounds of good judgment. It isn’t too difficult to let each audience member feel as though you’re speaking to him or her. However, you would not become so informal that you allow your carefully prepared speech to lapse into shallow entertainment. With larger audiences, it’s more difficult to reach out to each listener, and your speech will tend to be more formal, staying more strictly within its careful outline. You will have to work harder to prepare visual and audio material that reaches the people sitting at the back of the room, including possibly using amplification.

Occasion

There are many occasions for speeches. Awards ceremonies, conventions and conferences, holidays, and other celebrations are some examples. However, there are also less joyful reasons for a speech, such as funerals, disasters, and the delivery of bad news. As always, there are likely to be mixed reactions. For instance, award ceremonies are good for community and institutional morale, but we wouldn’t be surprised to find at least a little resentment from listeners who feel deserving but were overlooked. Likewise, for a speech announcing bad news, it is likely that at least a few listeners will be glad the bad news wasn’t even worse. If your speech is to deliver bad news, it’s important to be honest but also to avoid traumatizing your audience. For instance, if you are a condominium board member speaking to a residents’ meeting after the building was damaged by a hurricane, you will need to provide accurate data about the extent of the damage and the anticipated cost and time required for repairs. At the same time, it would be needlessly upsetting to launch into a graphic description of injuries suffered by people, animals, and property in neighboring areas not connected to your condomium complex.

Some of the most successful speeches benefit from situational analysis to identify audience concerns related to the occasion. For example, when the president of the United States gives the annual State of the Union address, the occasion calls for commenting on the condition of the nation and outlining the legislative agenda for the coming year. The speech could be a formality that would interest only “policy wonks,” or with the use of good situational audience analysis, it could be a popular event reinforcing the connection between the president and the American people. In January 2011, knowing that the United States’ economy was slowly recovering and that jobless rates were still very high, President Barack Obama and his staff knew that the focus of the speech had to be on jobs. Similarly, in January 2003, President George W. Bush’s State of the Union speech focused on the “war on terror” and his reasons for justifying the invasion of Iraq. If you look at the history of State of the Union Addresses, you’ll often find that the speeches are tailored to the political, social, and economic situations facing the United States at those times.

Voluntariness of Audience

A voluntary audience gathers because they want to hear the speech, attend the event, or participate in an event. A classroom audience, in contrast, is likely to be a captive audience. Captive audiences are required to be present or feel obligated to do so. Given the limited choices perceived, a captive audience might give only grudging attention. Even when there’s an element of choice, the likely consequences of nonattendance will keep audience members from leaving. The audience’s relative perception of choice increases the importance of holding their interest.

Whether or not the audience members chose to be present, you want them to be interested in what you have to say. Almost any audience will be interested in a topic that pertains directly to them. However, your audience might also be receptive to topics that are indirectly or potentially pertinent to their lives. This means that if you choose a topic such as advances in the treatment of spinal cord injury or advances in green technology, you should do your best to show how these topics are potentially relevant to their lives or careers.

However, there are some topics that appeal to audience curiosity even when it seems there’s little chance of direct pertinence. For instance, topics such as Blackbeard the pirate or ceremonial tattoos among the Maori might pique the interests of various audiences. Depending on the instructions you get from your instructor, you can consider building an interesting message about something outside the daily foci of our attention.

Physical Setting

The physical setting can make or break even the best speeches, so it is important to exercise as much control as you can over it. In your classroom, conditions might not be ideal, but at least the setting is familiar. Still, you know your classroom from the perspective of an audience member, not a speaker standing in the front—which is why you should seek out any opporutunity to rehearse your speech during a minute when the room is empty. If you will be giving your presentation somewhere else, it is a good idea to visit the venue ahead of time if at all possible and make note of any factors that will affect how you present your speech. In any case, be sure to arrive well in advance of your speaking time so that you will have time to check that the microphone works, to test out any visual aids, and to request any needed adjustments in lighting, room ventilation, or other factors to eliminate distractions and make your audience more comfortable.

Key Takeaways

- Demographic audience analysis focuses on group memberships of audience members.

- Another element of audience is psychographic information, which focuses on audience attitudes, beliefs, and values.

- Situational analysis of the occasion, physical setting, and other factors are also critical to effective audience analysis.

Exercises

- List the voluntary (political party, campus organization, etc.) and involuntary (age, race, sex, etc.) groups to which you belong. After each group, write a sentence or phrase about how that group influences your experience as a student.

- Visit www.claritas.com/MyBestSegments/Default.jsp and homes.point2.com and report on the demographic information found for several different towns or zip codes. How would this information be useful in preparing an audience analysis?

- In a short paragraph, define the term “fairness.” Compare your definition with someone else’s definition. What factors do you think contributed to differences in definition?

- With a partner, identify an instance when you observed a speaker give a poor speech due to failing to analyze the situation. What steps could the speaker have taken to more effectively analyze the situation?

References

- Grice, G. L., & Skinner, J. F. (2009). Mastering public speaking: The handbook (7th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. (2008, February). Summary of key findings. In U.S. religious landscape survey. Retrieved from http://religions.pewforum.org/reports#

- Tannen, D. (1994, December 11). The talk of the sandbox: How Johnny and Suzy’s playground chatter prepares them for life at the office. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www9.georgetown.edu/faculty/tannend/sandbox.htm