8.11: Arabic and Romance- A Comparison (Optional)

- Page ID

- 199990

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)8.10.1 Arabic and Romance: A Comparison (Optional)

Video Script

The last piece on historical linguistics—and this is purely optional; if you're not interested at all in this, you can skip watching or reading this, and it will not be on the historical linguistics quiz. I really want to go into this concept of Arabic and the fact that it is not a single monolithic language. Actually, if you look at the history of Arabic, and if you look at the modern usage of it, it's a lot more like the Romance family. So, we can talk about the Arabic family or the Arabic languages, and there's actually a good amount of comparison.

When you go to study Arabic, usually what you're learning is Modern Standard Arabic (MSA); it is the Arabic that is used in writing, broadcasting, speechmaking, education, and many regions have adopted it as its official language. I phrased myself very purposefully; MSA is not necessarily what people speak on a day-to-day basis. Many of you who speak ‘Arabic’, the truth is you probably speak an Arabic that is specific to the region or speech community based on where you and your family come from.

Let’s go back to that sociolinguistic definition of a language versus a dialect, and talk about mutual intelligibility. Is Arabic a single language with many dialects? Or, are they many related languages? Or are they something in between, something in progress? That's the main question.

This wasn't my initial question; this wasn't an initial thought that I had. This question and topic came from a student from fall of 2020 who wanted to know more about Arabic and why, for example, his mother spoke one version and his father spoke a different version; they were very different.

Here's the reality when we're talking about Arabic: there are multiple versions of this. Classical Arabic is the language of the Quran, the holy book of Islam. It is also the language of Islam, as far as anything liturgical or anything having to do with religion; it is almost always in Classical Arabic. The old writings are in Classical Arabic. Modern Standard Arabic is what you learn in a classroom; it is what you hear in mass media, as I said. I lingua franca, if you will, of the Arabic-speaking world. It is the one that everybody learns. It is a modernization of Classical Arabic, but a specific component of it is the fact that it is not of one place or one region. It is kind of like the overarching language that people will use in an international setting, or in an official government setting. But then in their day-to-day lives, they have their colloquial Arabic. In many cases, it's written down, although not always; when you see written Arabic, it is Modern Standard Arabic almost always, especially in a textbook or something like that.

It is also important when we're talking about the speech communities, if you know anything about the cultures associated with them, you know that there is a big difference between a sedentary speech community and a Bedouin speech community. The Bedouin in some cases, especially anthropologically, refers to a specific culture. But I’m going to use it in its more macro concept, which is a group of people, a speech community, that do not stay in one place. They move around; it is part of their pattern, to be migratory. In northern Africa, in parts of Arabia and the Levant, even Central Asia, you have Bedouin societies. These are all migratory societies; that's going to come into play with respect to any language family, but certainly when we're talking about Arabic. The sedentary speech communities are the ones that are established in a city or region; they don't move around, they don't migrate.

Let's talk about Arabic. When we say ‘Arabic’, let's focus on Colloquial Arabic.

The major regions of Colloquial Arabic are as follows:

- Saharan Africa;

- A little bit of Sub-Saharan Africa

- Parts of the Levant

- Parts of Arabia

- A little bit of the Persian Gulf

Keep in mind: we're not going to include any of the Arabic that spoken outside of this region, because that is more having to do with immigration patterns going out, the diaspora.

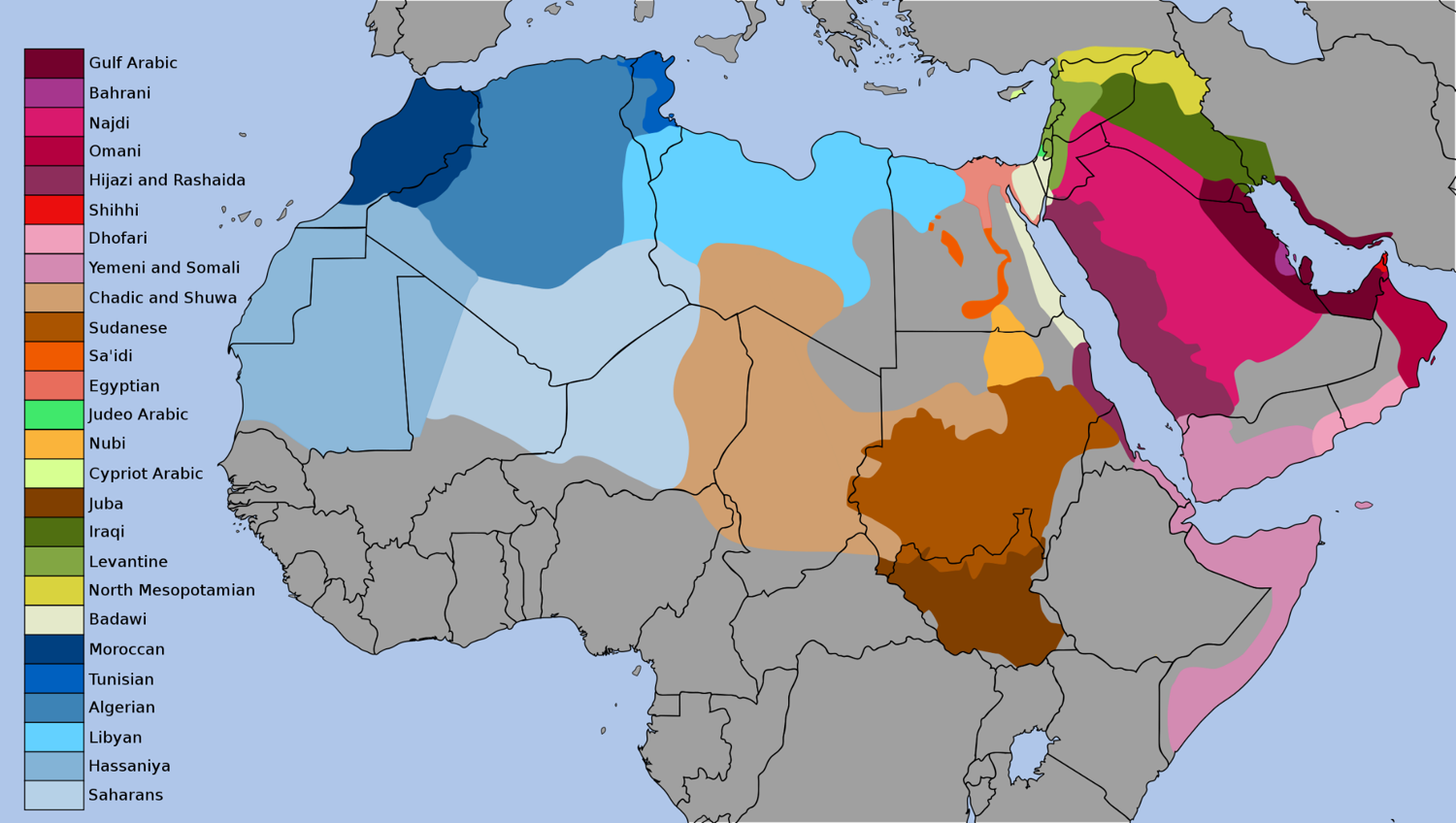

Notice some holes: we've got the Nilo-Saharan languages in this region, also Aramaic, and a number of the other languages of eastern Africa. In the Arabian Peninsula, we have a few more Afro-Asiatic languages. What is not marked in here is Hebrew; where modern Hebrew is spoken, we also have Arabic, specifically Levantine Arabic. You can see the different colors in the representation here

To give you a more concrete example, let me show you how to say a straightforward sentence

| Variety | I love reading a lot. | When I went to the library, | I only found this old book. | I wanted to read a book about the history of women in France. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modern Standard Arabic |

أَنَا أُحِبُّ القِرَاءَةَ كَثِيرًا |

عِنْدَمَا ذَهَبْتُ إِلَى المَكْتَبَة |

لَمْ أَجِد سِوَى هٰذَا الكِتَابِ القَدِيم |

كُنْتُ أُرِيدُ أَنْ أَقْرَأَ كِتَابًا عَن تَارِيخِ المَرأَةِ فِي فَرَنسَا |

| Maltese | jien inħobb naqra ħafna | meta mort il-librerija | sibt biss dan il-ktieb il-qadim | ridt naqra ktieb dwar il-ġrajja tan-nisa fi Franza. |

| Tunisian (Tunis) | nḥəbb năqṛa baṛʃa | wăqtəlli mʃit l-əl-măktba | ma-lqīt kān ha-lə-ktēb lə-qdīm | kənt nḥəbb năqṛa ktēb ʕla tērīḵ lə-mṛa fi fṛānsa |

| Algerian (Algiers) | ʔāna nḥəbb nəqṛa b-ez-zaf | ki rŭħt l-əl-măktaba | ma-lqīt ḡīr hād lə-ktāb lə-qdīm | kŭnt ḥayəb nəqṛa ktāb ʕla t-tārīḵ təʕ lə-mṛa fi fṛānsa |

| Moroccan (Casablanca) | ʔāna kanebɣi naqra b-ez-zāf | melli mʃīt el-maktaba | ma-lqīt ḡīr hād le-ktāb le-qdīm | kunt bāḡi naqra ktāb ʕla tārīḵ le-mra fe-fransa |

| Egyptian (Cairo) | ʔana baḥebb el-ʔerāya awi | lamma roḥt el-maktaba | ma-lʔet-ʃ ʔella l-ketāb el-ʔadīm da | kont ʕāyez ʔaʔra ketāb ʕan tarīḵ es-settāt fe faransa |

| Northern Jordanian (Irbid) | ʔana/ʔani kṯīr baḥebb il-qirāʔa | lamma ruḥt ʕal-mektebe | ma lagēteʃ ʔilla ha-l-ktāb l-gadīm | kān baddi ʔagra ktāb ʕan tārīḵ l-mara b-faransa |

| Jordanian (Amman) | ʔana ktīr baḥebb il-qirāʔa | lamma ruḥt ʕal-mektebe | ma lagēt ʔilla hal-ktāb l-gadīm | kan beddi ʔaqraʔ ktāb ʕan tārīḵ l-mara b-faransa |

| Lebanese (Beirut) | ʔana ktīr bḥebb l-ʔ(i)rēye | lamma reḥt ʕal-makt(a)be | ma l(a)ʔēt ʔilla ha-le-ktēb l-ʔ(a)dīm | kēn badde ʔeʔra ktēb ʕan tērīḵ l-mara b-f(a)ransa |

| Syrian (Damascus) | ʔana ktīr bḥebb l-ʔirēye | lamma reḥt ʕal-maktbe | ma lʔēt ʔilla ha-l-ktēb l-ʔdīm | kān biddi ʔra ktāb ʕan tārīḵ l-mara b-fransa |

| Gulf (Kuwait) | ʔāna wāyid ʔaḥibb il-qirāʾa | lamman riḥt il-maktaba | ma ligēt ʔilla ha-l-kitāb il-qadīm | kint ʔabī ʔagra kitāb ʕan tarīḵ il-ḥarīm b-faransa |

| Hejazi (Jeddah) | ʔana marra ʔaḥubb al-girāya | lamma ruħt al-maktaba | ma ligīt ḡēr hāda l-kitāb al-gadīm | kunt ʔabḡa ʔaɡra kitāb ʕan tārīḵ al-ḥarīm fi faransa |

| Sanaani Arabic (Sanaa) | ʔana bajn ʔaḥibb el-gerāje gawi | ḥīn sert salā el-maktabe | ma legēt-ʃ ḏajje l-ketāb l-gadīm | kont aʃti ʔagra ketāb ʕan tarīḵ l-mare wasṭ farānsa |

| Mesopotamian (Baghdad) | ʔāni kulliš ʔaḥebb lu-qrāya | min reḥit lil-maktaba | ma ligēt ḡīr hāḏa l-ketab el-ʕatīg | redet ʔaqra ketāb ʕan tārīḵ l-imrayyāt eb-fransa |

I have Modern Standard Arabic as the top, so that you can see how it is set up, this is the script, this is the, shall we say, Latin alphabet version of it, and then you have the IPA is the third. In the rest of the column is all IPA. You also see Maltese, Tunisian, Algerian, Casablanca-based Moroccan, Cairo-based Egyptian, northern Jordanian, Amman-based Jordanian, Beirut-based Lebanese, Damascene Syrian, Gulf Kuwaiti, Hejazi in Saudi Arabia, Sanaani Arabic from a different part of Arabian Peninsula, and then Baghdadi or Mesopotamian Arabic. There are lot of differences! Notice a few things:

- There's a case system that you see in Modern Standard Arabic, that may or may not exist in the other versions.

- You will also see word order changes; look at I love reading a lot, at the order of the second and third lexicon. Sometimes there's a fourth, by the way; if you look down this column, sometimes it's three and sometimes it's four, and there's a different order.

- Although you don't see it in here, there's a passive voice that is different; it's set up different in all these different regions.

- Some of these varieties of Colloquial Arabic have singular versus plural, and some have added a dual.

- There is a shift in the vowels.

- There are consonant cluster differences.

If you go back to the map, it kind of clusters; Realistically, you have six main regions.

- In northern Africa, this is called Maghrebi. There is more influence from the indigenous languages of that region, Berber in particular. You have also a little bit of Romance languages because notice it's right on the Mediterranean; it's going to have contact with Spanish, a little bit of Portuguese, it's going to have contact with French, especially given that in this region French is an official language. These were some of the last territories that France gave up, so the French connection is very strong. Because of that, you're going to have more borrowings, especially from French, but maybe even from Spanish or Italian. You also have Punic languages as an influence—that would be Phoenician, or more specifically Carthaginian—historically derived languages from those regions.

- Sudanese: you have more contact with Nubian languages from the Nilo-Nubian languages in particular. Sudanese and Chadian are the two main colloquial Arabics from that region, but there's some others.

- Egyptian Arabic: there's going to be more influence from Coptic languages and other Afro-Asiatic languages that are indigenous to that region.

- Mesopotamian: think Mesopotamia, the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. This area is going to have influence from the languages from eastern Turkey—some of them are Turkic and some of them are Anatolian, based off the Hittites—as well as influence from Iranian languages, especially Farsi. The Arabic spoken in Baghdad, for example, is going to be different than the Arabic spoken to the south.

- The Levant: This is frequently the area that we considered to be Israel, Lebanon, Syria, a bit of Jordan, and parts of the southern and central areas of Iraq. In those cases, you've got some Turkish and some Greek; that makes sense, historically. There is some influence from the indigenous languages from that area. Aramaic comes in, so another Afro-Asiatic language that's historically been in that region for some time.

- Peninsular Arabic: The big obvious one would be Saudi Arabia as a country, but you've got a little bit of the southern edge of Iraq and of the eastern half of Jordan. The indigenous languages of the Arabian Peninsula filter in here.

What does this mean?

If you have somebody from Morocco trying to some talk to somebody from Syria, those are two different Arabics, and they can be radically different. In fact, Tunisian, Algerian, Moroccan, even Maltese, they're pretty close. Compare this to Lebanese or Syrian, which are both very different to the Maghrebi Arabics. There are entire combinations of sounds that you don't see in the other section.

Why bring this up?

Historically, folks like to think of Arabic as a monolithic concept that just has multiple dialects. Remember when we talked about a language versus a dialect, and we were talking about mutual intelligibility. I don't know about you, I certainly am not an expert in Arabic, I do not speak Arabic and anyway, I don't speak any Afro-Asiatic language…but I can look at these data, and I can compare and contrast. Even if I don't have the glosses, the morpheme, or lexicon-by-lexicon, morpheme-by-morpheme translation of what these concepts are, I can just see that Levantine is very different from Modern Standard Arabic, or from Maghrebi, or from Mesopotamian. I can use my eyes and ears, and see and hear that. This is not just in the minor intelligibility difficulties; this is not like saying, “It's kind of hard to hear and understand somebody from Australia or Scotland.” If they slow down and they speak clearly, we can understand them as Americans. But somebody from Casa Blanca in Morocco cannot necessarily understand somebody from Damascus, Syria. That's a question about mutual intelligibility.

What does this have to do with the Romance languages?

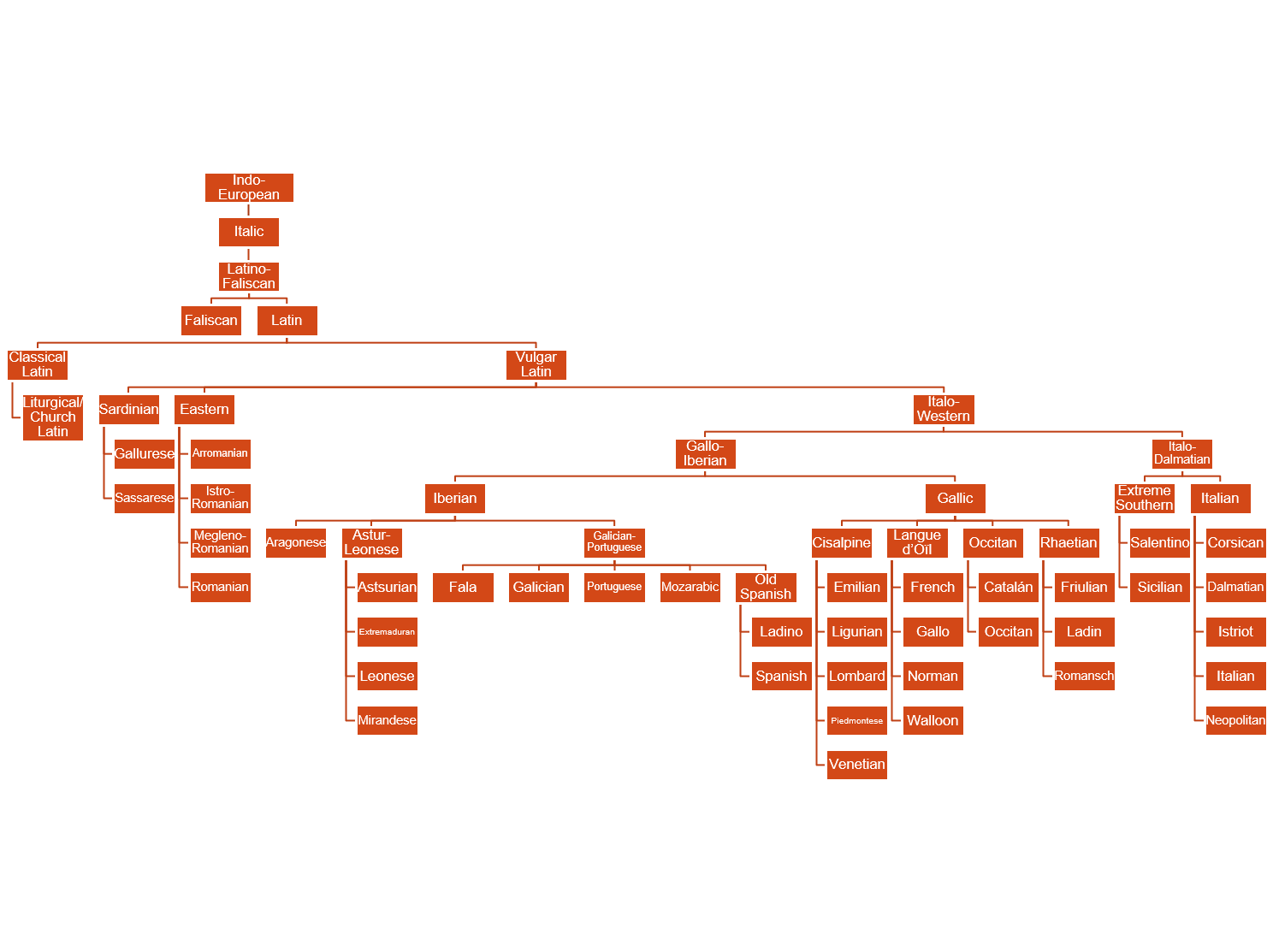

Here is the full Indo European tree.

Remember that when we're talking about the Romance family, we're talking about the languages that derived from Latin—Latin is not a Romance language, rather it's the parent of the Romance languages. If you take somebody from Madrid, Spain and you plop them into Rome, Italy, there are some things that are in common, but there's a lot that's different. Some of the sounds might be the same, but the some of the morphology isn't; the syntax might be generally the same, but there might be some differences. If you take that same person from Madrid and put them in Sardinia, now you got something totally different; Sardinian is a very distinct language. (Unfortunately, it is dying out; I wish it weren't, because it's a very beautiful language.) It encapsulates, it keeps so many of the archaic elements that we see in Vulgar Latin. Therefore, if you're going from Madrid, Spain, to Sardinia, that's really difficult, linguistically. If you take that same person from Madrid and put them into Paris, now you're talking big changes. Granted, most all of them are phonological, but there are morpho-syntactic changes there are semantic changes. You can't just go by the cognates, because sometimes they are radically different. Now, take that same person, and put them in to Bucharest, Romania. That is a radically different linguistic landscape, even more different than anything else they've heard before. Yes, these are all Romance languages and, believe it or not, if you can read one Romance language, you've got a pretty good idea of what's going to happen in the other Romance language. It may not be exact, but it's pretty good. I’m fluent in Spanish and Italian, and I speak a little bit of Portuguese. I can look at French and get 70% of what's there; I can look a Romanian and get about 65% of what's there. When French and Rumanian have been spoken to me, I get a chunk of it; some of it sounds familiar, but a lot of it doesn't.

Why is this a good comparison to Arabic?

Because it's a lot of the same concepts.

For the Romance languages, we have no problem at all saying that those are different languages, that the two dialects of Sardinian, Romanian, the various Spanish dialects, Italian and its various dialects, Galician, Portuguese, French, Romansch, on and on. We have no problem saying that those are different languages. Why can't we say that for Arabic? By the way, this is not just a European-minded person saying that; even within Arabic scholars, many of them refused to say that those are different languages.

Let me show you another way that we can say that those are different languages in Arabic. If we look at the history of the Romance languages, when we go from Latin to the Early Romance period—remember that Latin as a concept, even Vulgar Latin and Late Latin, more or less end with the fall of the Roman Empire. In total for the Romance languages, we have 2000 years of history. At the end of second century CE, or the end of the 100s CE, that's when we get Vulgar Latin turning into Common Latin. When we say Early Romance, we're talking around 850-900 CE; the fall of the Roman Empire is in the early sixth century, or the early 500s CE. That means that there are about 300 years where we have little bits and pieces, but not books, written in whatever the local languages are—not in Latin. This is the overall timeline for the Romance languages.

Notice the same timeline for the Arabic languages: Old Arabic is in the first century CE, and then Classical Arabic starts around third century CE, and then all the way through to the modernization, which is the 19th century. Pretty similar.

In the earliest of the Romance languages, we already started seeing a reduction in the case system, we see a fixed and changed word order. Although you could play with it, Latin was predominantly a subject-object-verb (SOV) word order; Romance languages early on fix that to SVO because they don't have case anymore. Guess what you see with Arabic? A reduction or loss of case system from Classical to Modern Arabic, and it changed word order. There is a more synthetic morpho-syntax for both groups. See where I’m going?

You have various changes semantically and morpho-semantically. This includes the loss of the middle voice, which is something I can explain in a different time. (If you have active voice and passive voice, Latin used to have a middle voice.) There is a loss of the neuter gender actually in vulgar Latin. There is a different passive construction from Classical Arabic to Modern Arabic, as well as a different number system. There are changes that reflect both the phonology, syntax, and the semantics. There are changes in deixis, different moods; we talked about the energetic that we saw in Modern Arabic, but in most Colloquial Arabics, so you don't have the energetic. The variations in lexicon, influence of the morpho-syntax, influence on the morpho-semantics, they all pattern the same way and across the same amount of time.

Again, I bring up this question: If we can say that the Early Romance languages started separating out and started individualized across 2000 years of history, why can’t we say that for Arabic and the Arabic languages, if you will?

I'll bring up one more point: This use of Classical Arabic and then later on Modern Standard Arabic, these all have to do with formal education and formal governments. The same is true with Latin; first it was Classical Latin and then what was called Late Latin or Medieval Latin. Those were used at very high levels, the educated highest educated people only. Common folks did not use this, and what we're seeing—certainly with Classical Arabic, but even with Modern Standard Arabic—in many places, people are eschewing the use of Modern Standard Arabic. They understand it; if they turn on the radio or TV, or if they pick up a paper, they understand it. But they do not speak it. This really is suggesting that these Colloquial Arabics are different languages.

When I say that linguists have to be objective, we have to pull back, we have to be descriptive of what we see and observe and hear, and we have to document it accordingly, this also means revising our definitions. There isn't an Arabic language. There are many Arabic languages. And this is just Arabic; there are many other languages that we could also revisit with this kind of observation and comparison. We can say, “Okay, we don't have one language; we have several.”