Video Script

I've been fortunate to teach foreign language for over 20 years, and it's been an interesting ride in those 20 years plus. The additional 10 or so beforehand, when I was learning a foreign language, these teaching methods changed just in my own lifetime, very drastically. While most of what you're going to see on this next slide is not in use anymore (thankfully), it certainly represents what most people had to suffer with respect to foreign language learning. I do use the term suffer because when we're talking about grammar translation and audio call and response, these are techniques that have been used for millennia, and with respect to language learning and they don't work. For a very small portion of the population, they actually do help, but for the most part we have left these methods behind. Grammar translation is when you have a term in language one, and then you have the term in language two, and you are supposed to repeat. It's usually a call-and-response type of scenario; I say 'this is not a hat'; 'este no es un sombrero’. You, the student, are supposed to say 'este no es un sombrero'. The lesson would go from there. It doesn't work because it does not actively engage the synapses so that you actually remember. What you're trying to say and what everything means. Remember that first rule of language: everything is arbitrary. If you do not see the pattern, you're not going to see how and why you should remember something, and it just won't stick.

For the last 40 years, we have moved away from that grammar translation, call-and-response mentality, and have been in the content-based instruction mode. There are two main flavors of this. The first is immersion, when you immerse yourself in the language 100% of the time. The usual case is that the person moves to a location that speaks that language, and then lives within the population and learns—not through osmosis, might I add—but the input. They're combining what they’re hearing around them with classes. It must be said, immersion is all about motivation. For example, if you are forced to move to a new area that speaks a completely different language, you may not have a lot of motivation to learn that new language, you may feel a bunch of resentments, and therefore try to not learn that language. Or, you may be highly motivated because you need a job, so that you can earn money, and therefore be able to afford things. Everybody's motivation is going to be different, and an immersion scenario usually accelerates the motivation in one path or the other.

What we tend to do in a classroom is much more communicative; let me explain what that is. When we talk about the communicative approach, mostly we're talking about the work of Stephen Krashen, Bill Van Patten, and a number of others, starting in the late 70s and through to today. Recently, Bill van Patten published a new book about three years ago. The communicative approach is just that: acknowledging that language is a tool, and that we use it to communicate with others. There have been multiple iterations of the communicative approach over the last 40 years, and it is all based off of information that we know to be true, based off of observation and, in the last five years, what we've been able to show as far as how the brain processes language. (More on that in the next chapter.) Suffice to say that so many of the theories that we've come up with over the last 40 years as to how we learn language, how we process language, and how to improve the language learning environment, we're starting to see evidence of that with respect to the neural processing. It is a fascinating time right now to start understanding how language and the brain work.

For now, let's focus on the communicative approach. It's an active learning environment, so you really focus on getting the students to practice the language in multiple ways. The five Cs are the core: communication, culture, comparisons, connections, and communities. When you learn a language in a communicative approach, you are not simply learning the grammar and the vocab; you're learning the culture behind it, or cultures in the case of multicultural languages. You're making comparisons between your first language and this one, and perhaps any others you've learned along the way. You're making connections in a variety of ways: neural connections, the literal connections with respect to the language learning, but also connections with other peoples and then communities, which is you're communicating with other communities, not just locally, but around the world. It is important to remember that, with this communicative approach, we involve technology; this communicative approach starts off just as we were starting to have personal computers, and it really takes off in the 1990s, when we start to have Internet in all homes. Not surprisingly, with the Internet, you can then communicate with the world, literally. Harnessing that power of communication in the language classroom is incredibly important; it can be a hindrance, or it can be a help.

Personally, in my practice, I have always included communications with technology, even at its earliest stages. I was using the Internet to learn languages myself through online bulletin boards or chat. By talking and typing in the languages, I was learning to facilitate; at one point in my life, I could chat English, Spanish and Italian pretty much at the same time. (Those days are long gone, by the way; now, it's two at a time, at most.) That being said, if you encourage students to use the technology to push them forward, as a way to apply that knowledge—to read about something in that new language they're learning and then report on it, to talk to somebody whether it is live or it is email, to investigate a little bit more about that culture and then report back on it—these are ways that technology can help.

But technology in the language learning classroom can be a hindrance. The worst thing that a person can do is try to use some kind of app or website to translate everything. For one, it's not going to work and it's not going to work for some time yet; processors just do not function at that speed with all the permutations possible to give the correct translation. Most trained multilinguals can spot it every single time. The other reason that it does not work is because it is passive. One of the things I tell my students, regardless of the level of Spanish they're in, is I require them to be active in their learning. If you are looking up every single word, that's passive; you're not going to remember any of the vocabulary that you looked up. It's the same as the grammar translation; that never works. If you use that term that you look up, by using it in your speaking in your writing, and then later you hear it, and process it—that is what works. This active learning process gets ingrained into your mental lexicon for that language. That is how technology can be used as a tool.

(And no, Apple Translate and Google Translate should not exist; they need to be abolished. 😝)

Flipped classrooms are a part of this concept, where you put the onus of the learning on the student. While the foreign languages have been doing this for some time, we got the idea from a lot of vocational or career technical programs. This scenario is where the student needs to read up and learn about certain processes in that course ahead of the class meeting, and then they come to the lab or they come to the classroom and apply it. If you're in a culinary program, you read about different culinary techniques, and then you go into the kitchens on campus and you apply them. If you're in an automotive program, you learn about a specific system, the transmission or the exhaust system or what have you, and then you go into the mechanic shop and you practice it. Foreign language classrooms have been moving to a flip model for some time; I’ve been teaching in a flipped model for about 15 years. It really does put the onus of the learning on the student; the student has to take that responsibility. But that's also how you foster two aspects that are really important in combating learner affect: If you put the responsibility for learning on the students, they find the motivation, they want to come to class prepared, or at least with the questions that they need answered. You also break down that learner affect because the student will take that skill that they read about at home. In the classroom, we're going to apply it; I’m going to have you read something and then I want you to tell me about it. Or, I'm going to have you write something to a person or colleague, or to a random person that doesn't exist. I'm going to have you tell a story or write a story; I’m going to have you give your version of Little Red Riding Hood or Sleeping Beauty or whatever folk tale you wish to use. When you use a flipped classroom with active learning, at its core language learning isn't so terrible. When you chunk the learning—meaning you break it down to little pieces and present those chunks in ways that students can acquire on their own—and then apply it in the classroom, suddenly the process isn't quite so onerous.

The last real thing that we're going to talk about with respect to language learning and teaching methodologies has to do with proficiency versus fluency. It is interesting when somebody tells me that they are fluent in a language, and especially if it's a language I happen to share, and then I will see what that fluency really is about. The popular concept of fluency is something along the lines of, “I can make a basic conversation. I can maybe use some past tense, but I mostly stay in the present tense, because what else do I really need. I can go travel to a place, I can get food or water, do some kind of activity. In my eyes, I'm fluent in the language.”

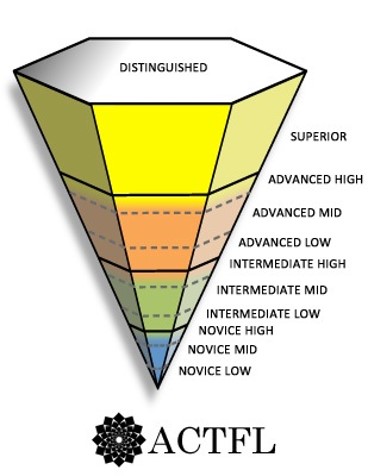

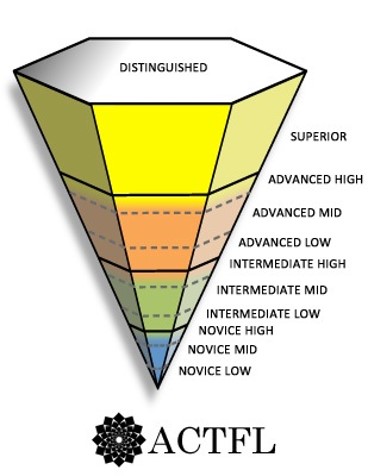

The problem is when it comes to teaching methods, that's not fluency at all. What you see over here is the ACTFL pyramid; ACTFL is the American Council for the Teaching of Foreign Language. They're one of the preeminent academies, if you will, or associations with respect to language learning.

This inverted pyramid describes what you can do when you first start out, all the way up to the most distinguished and elevated speaker of that language. It doesn't matter what language we're talking about. When you start off, you're at a Novice level; you can make a list of things that you like or dislike, or attributes of something. You're only speaking in the present tense, and your vocabulary is very limited. When you're an Intermediate level, you're starting to branch into a couple of different tenses—not drastic, but a little bit more. You have a more robust vocabulary, but there's still plenty of holes. This is where most people's concept of being fluent is because, in truth, they're not really that fluid. They're really only speaking in the present tense and that's about it. For a linguist or a foreign language professional, in order to be fluent, you need to be in the Advanced level. It means that you modulate your verb structures, so you're using tense, aspect, and mood, those aspects we talked about deixis, semantics and pragmatics. If you recall, many languages have two, if not three tenses. Frequently, there's multiple aspects and there's different moods. If you're an advanced speaker, you're able to use those pieces, and you're able to convey so much more. A novice speaker really is only able to talk about themselves, and maybe immediate family. Intermediate speakers can talk about their immediate community, like their neighborhood. Advanced speakers can talk about their larger neighborhood. Superior is when you are fully fluent; you are a native or near-native, fully fluent speaker. You're able to talk hypotheticals, you're able to talk about potentials, and you're able to talk about massive complex sentence structures that usually involve a goodly amount of discussion.

What is really important with respect to this, is that language is a tool. We use the tool as a skill; I've used that metaphor throughout the course. This pyramid shows us that we always have room to grow.

The very top level is Distinguished, and there are very few Distinguished speakers of any language. For example, I’m a native speaker of English, I have a PhD in Linguistics—yet I am not a Distinguished speaker of English; I am Superior. I can do all of these things: talk all of these complex causal structures, and hypotheticals, and everything that you want. I can write an academic language. But to be a Distinguished person, that would be the highest level of legal language that you can think of. I do not speak legal-ese, as it were, so I’m not there. Most people who have a full formal education, usually through the concept of high school and maybe even a little bit of college, you're going to be in the Superior, or at least Advanced-High level. It's not to say that if you do not have formal education, you can't be up here in the Superior level; it just means you have to get your education from elsewhere. You can be a Superior level speaker in your native language and not have formal education. If you're consistently using hypotheticals, thinking about more than just your immediate society, talking about national or global society—when you start expanding with your language, that is when you come into those higher levels.

That's an important thing to bring up for everyone with respect to language: Push yourself, even in your native language or languages. Keep pushing yourself; keep reading; keep talking; keep expanding what you can do with that tool. You don't just learn to boil water in a cooking class; you learn how to cook, how to make a sandwich, or make a soup. You make some pretty important things; language is no different.