Seeing the Social World in A New Light: Personal & Larger

Social

The average person lives too narrow a life to get a clear and

concise understanding of today’s complex social world. Our daily

lives are spent among friends and family; at work and at play. We

spend many hours watching TV and surfing the Internet. No way can

one person grasp the big picture from their relatively isolated

lives. There are thousands of communities, millions of

interpersonal interactions, billions of Internet information

sources, and countless trends that transpire without many of us

even knowing they exist. What can we do to make sense of it

all?

When I learned of the sociological imagination by Mills, I

realized that it gives us a framework for understanding our social

world that far surpasses any common sense notion we might derive

from our limited social experiences. C. Wright Mills (1916-1962)

was a contemporary sociologist who brought tremendous insight into

the daily lives of society’s members. Mills stated that “neither

the life of an individual nor the history of a society can be

understood without understanding both" (Mills, C. W. 1959. The

Sociological Imagination page ii; Oxford U. Press). Mills

identified “Troubles” (personal challenges) and "Issues" (Larger

social challenges) that are key principles for providing us with a

framework for really wrapping our minds around many of the hidden

social processes that transpire in an almost invisible manner in

today’s societies. Before we discuss personal troubles and larger

social issues let’s define a social fact.

Social Facts are social processes

rooted in society rather than in the individual. Émile

Durkheim (1858-1917, France) studied the “science of social facts”

in an effort to identify social correlations and ultimately social

laws designed to make sense of how modern societies worked given

that they became increasingly diverse and complex(see Émile

Durkheim, The Rules of the Sociological Method, (Edited by Steven

Lukes; translated by W.D. Halls). New York: Free Press, 1982, pp.

50-59). See the Sociological Imagination diagram below.

The national cost of a gallon of gas, the War in the Middle

East, the repressed economy, the trend of having too few females in

the 18-24 year old singles market, and the ever-increasing demand

for plastic surgery are just a few of the social facts at play

today. Social facts are typically outside of the control of average

people. They occur in the complexities of modern society and impact

us, but we rarely find a way to significantly impact them back.

This is because, as Mills taught, we live much of our lives on the

personal level and much of society happens at the larger social

level. Without knowledge of the larger social and personal levels

of social experiences, we live in what Mills called a False

Social Conscious which is an ignorance of social facts and the

larger social picture.

Personal troubles are private problems

experienced within the character of the individual and the range of

their immediate relation to others. Mills identified the

fact that we function in our personal lives as actors and actresses

who make choices about our friends, family, groups, work, school,

and other issues within our control. A college student who parties

4 nights out of 7, who rarely attends class, and who never does his

homework has a personal trouble that interferes with his odds of

success in college. On the other hand, when 50 percent of all

college students in the country never graduate, we call that a

larger social issue.

Larger Social Issues are those that lie

beyond one's personal control and the range of one's inner

life. These pertain to society's organizations and

processes. These are rooted in society rather than in the

individual. Nationwide, students come to college as freshmen

ill-prepared to understand the rigors of college life. They haven’t

often been challenged enough in high school to make the necessary

adjustments required to succeed as college students. Nationwide,

the average teenager text messages, surfs the net, plays video or

online games, hangs out at the mall, watches tv and movies, spends

hours each day with friends, and works at least part-time. Where

and when would he or she get experience focusing attention on

college studies and the rigors of self-discipline required to

transition into college credits, a quarter or a semester, studying,

papers, projects, field trips, group work, or test taking.

Figure 1. Diagram of the Seven Social Institutions and the

Sociological Imagination

© 2005 Ron J. Hammond, Ph.D.

In a survey conducted each year by the US Census Bureau,

findings suggest that, in 2006, the US had about 84 percent of the

population who graduated high school. They also found that only 27

percent had a bachelors degree. Given the numbers of Freshmen

students enrolling in college, the percentage with a bachelors

degree should be closer to 50 percent.

The majority of college first year students drop out, because

nationwide we have a deficit in the preparation and readiness of

Freshmen attending college and a real disconnect in their ability

to connect to college in such a way that they feel they belong to

it. In fact, college dropouts are an example of both a larger

social issue and personal trouble. Thousands of studies and

millions of dollars have been spent on how to increase a Freshman

student’s odds of success in college (graduating with a 4-year

degree). There are millions of dollars worth of grant money awarded

each year to help retain college students. Interestingly, almost

all of the grants are targeted in such a way that a specific

college can create a specific program to help each individual

student stay in college and graduate.

The real power of the sociological imagination is found in how

you and I learn to distinguish between the personal and social

levels in our own lives. Once we do, we can make personal choices

that serve us best, given the larger social forces that we face. In

1991, I graduated with my Ph.D. and found myself in a very

competitive job market for University professor/researcher.

positions. With hundreds of my own job applications out there, I

kept finishing second or third and was losing out to 10 year

veteran professors who applied for entry level jobs. I looked

carefully at the job market, keeping in mind my deep interest in

teaching, the struggling economy, and my sense of urgency in

obtaining a salary and benefits. I came to the decision to switch

my job search focus from university research to college teaching

positions. Again, the competition was intense. On my 301st job

application (that’s not an exaggeration),I interviewed and beat out

47 other candidates for my current position. In this case, knowing

and seeing the larger social troubles that impacted my success or

failure helped in finding a position. Because of the Sociological

Imagination, I was empowered because I understood the larger social

job market ,and was able to best situate myself within it.

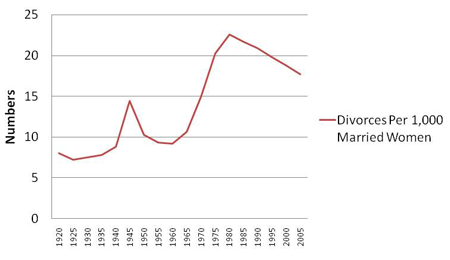

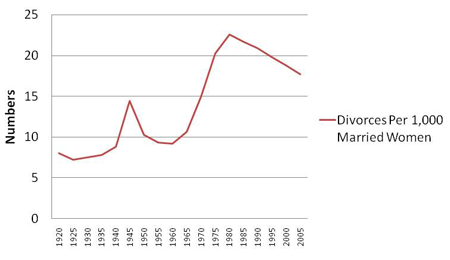

Making Sense of Divorce Using the Sociological Imagination

Let’s apply the sociological imagination to something most

students are deeply concerned about—divorce. Are there larger

social and personal factors that will impact your own risk of

divorce? Yes. In spite of the fact that 223,000,000 people are

married in the U.S., divorce continues to be a very common

occurrence (see http://www.Census.gov ). Divorce

happens and since millions of us (me included) had our parent’s

divorce, we are especially concerned about the success of our own

marriage.

What’s in the larger social picture? Estimates for the U.S.

suggest that 85 percent of us will marry (Popenoe, D. 2007 in 5

June, 2008 from marriage.rutgers.edu/Publicat...XTSOOU2007.htm ).

Yet, so many of us feel tremendous anxiety about marriage. Consider

the marriage and divorce rates in Table 1 below. The first thing

you notice is that both have been declining since 1990. The second

thing you notice is that the ratio of marriages to divorces is

consistently 2 marriages to 1 divorce (2:1). To point out, the

divorce and marriage rates in Table 1 are called Crude Divorce and

Crude Marriage rates because they compare the divorces and

marriages to everyone in the population for a given year, even

though children and others have virtually no risk of either

marrying or divorcing.

Table 1: Comparison of US Marriages/1,000 Persons to

Divorces/1,000 Persons 1990, 2000, and 2005*

|

1990 Rates |

2000 Rates |

2005 Rates |

3-year Average |

| US Marriages |

9.8/1,000 |

8.3/1,000 |

7.5/1,000 |

8.5/1,000 |

| US Divorces |

4.7/1,000 |

4.1/1,000 |

3.6/1,000 |

4.1/1,000 |

| US Ratio of Marriages to Divorces |

2:1 |

2:1 |

2:1 |

2:1 |

*Statistical Abstracts online: Table 121. Marriages and

Divorces—Number and Rate by State: 1990 to 2005 Taken from the

Internet on 5 June, 2008 from

www.census.gov/compendia/stat..._divorces.html

Does sociology provide personal and larger social insight into

what we can do to have a good marriage and avoid divorce?

Absolutely! However; before we discuss these, lets set the record

straight. There never was a 1 in 2 chance of getting divorced in

the U.S. ( see http://www.Rutgers.edu the

National Marriage Project, 2004 “The State of Our Unions” or Kalman

Heller “The Myth of the High Rate of Divorce taken from Internet 5

June, 2008 from http://www.isnare.com/?aid=217950&ca=Marriage

). Divorce rates peaked in the 1980’s and have steadily declined

since then (See Figure 1 below). Even though all married people are

at risk of divorce, most of them will not face this reality. Many

studies have consistently shown exactly how our personal choices

and behaviors can actually minimize our chances of divorce. Here’s

a brief summary:

-Wait to marry until you reach your mid-20’s. Teens who marry

have the highest risk of divorce (see Center for Disease

Control “First Marriage Dissolution, Divorce, and Remarriage:

United States taken from Internet 5 July, 2008 from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad323.pdf

).

(see Center for Disease

Control “First Marriage Dissolution, Divorce, and Remarriage:

United States taken from Internet 5 July, 2008 from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad323.pdf

).

-Avoid cohabitation if you plan to ever marry. While

cohabitation is on the rise in the U.S., it is still associated

with higher risks of divorce once one is married. Numerous studies

have rigorously researched the impact of having cohabited on the

odds of marital success. (see Lisa Mincieli and Kristin Moore, "The

Relationship Context of Births Outside of Marriage: The Rise of

Cohabitation," Child Trends Research Brief 2007-13 (May 2007); or

Matthew D. Bramlett and William D. Mosher, Cohabitation, Marriage,

Divorce and Remarriage in the United States, National Center for

Health Statistics, Vital and Health Statistics, 23 (22), 2002; Or

Larry Bumpass and Hsien-Hen Lu, "Trends in Cohabitation and

Implications for Children’s Family Contexts in the U. S.,"

Population Studies 54 (2000): 29-41; or Jay Teachman, "Premarital

Sex, Premarital Cohabitation, and the Risk of Subsequent Marital

Disruption among Women," Journal of Marriage and the Family 65

(2003): 444-455.

-Finish college. College graduates divorce less then dropouts or

high school graduates (see

mtsu32.mtsu.edu:11422/315/adu...divfactos.html ).

-Be aware of the three-strike issue: Strike 1, you are poor;

Strike 2, you are a teenager when you marry; and Strike 3, you are

pregnant when you marry. These issues could prove to be a terminal

combination of risk factors as far as staying married is concerned.

These three in combination with others listed below may increase

your risk of divorce.

-Know which factors you can control that will likely impact your

marital success odds. Other scientifically identified divorce risk

factors include: high personal debt; falling out of love; not

proactively maintaining your marital relationship; marrying someone

who has little in common with you; infidelity; remaining mentally

“on the marriage market…waiting for someone better to come along,”

having parents who divorced; neither preparing for nor managing the

stresses that come with raising children, and divorcing because the

marriage appears unhappy and hopeless in terms of resolving

negative issues ( see Glenn, N. 1991 “Recent trends in Marital

Success in the US” May, J. of Marriage and the Family, pages

261-270). Often couples on the fringe of divorce later emerge from

those states of unhappiness and hopelessness with renewed happiness

and hope, by simply enduring the difficult years together.

In all of these factors listed above you can decide how to best

situate yourself to deal with the certain issues before divorce

becomes the ultimate outcome. But, as Mills taught, you must

consider both personal and larger social issues simultaneously to

fully benefit from the sociological imagination. It is true that

divorce is still very common in the U.S. Notice the peak on this

figure found in the 1980s, and the trend (at least up to the most

recent 2005 data) shows a slightly decreased pattern since

then.

Figure 2: United States Historical Data-Divorce Trends 1920-2005

*

*US. Bureau of the Census Historical Statistics of the United

States, Colonial Times to 1970, Bicentennial Edition, Part 2;

Washington, D.C., 1975Series B 216-220 “Divorce 1920-1970 and

Statistical Abstracts of the United States 2001 Page 87 Table 117

and 2002 Page 88 Table 111.

What are some of the larger social factors that have

historically contributed to these patterns of divorce? You’ll

notice a brief spike in divorce after World War II. The post-war

year, 1946, was a true anomaly as far as rates measuring the family

are concerned. It was the highest rate of marriages, highest rate

of births (The Baby Boom began in 1946), and the lowest median age

at marriage in U.S. history. Divorce rates surged in 1946 as all

the soldiers returned home having been changed by the trauma,

isolation from their families, and challenges of the war. They were

probably less compatible with their wives once they came back.

Divorces tended to follow wars for marriages where one spouse is

deployed into combat (WWI, WWII, Vietnam, Korea, Kuwait, and

Iraq).

Other factors influencing this divorce pattern have to do with

the economy, marriage market, and other factors. Divorces continue

to be high during economic prosperity and often decline during

economic hardships. Divorces tend to be higher if there is an

abundance of single women in the society. And divorces tend to be

more common in: urban rather than rural areas; the Western US than

in the Eastern; among the poor, less educated, remarried, less

religiously devout, and children of divorce. Please note that

recession, war, secularism, and western US cultures don’t cause

divorce. Scientists have never identified a “cause” for divorce.

But, they have clearly identified risk factors.

Could there be larger social factors pressuring your marriage

right now? Yes, but you are probably not enslaved to those forces.

They still impact you, and you can follow Mill’s ideas and manage

as best you can within your power concerning consequences of these

forces. What can you do about it? Well, if you are single, you’d

best situate yourself in terms of marital success by waiting to

marry until you are in your 20’s, finishing and graduating from

college, paying careful attention to finding the right person

(especially one with common values similar to your own), and doing

some sort of self-analysis to assess working proactively to nurture

your marriage relationship on an ongoing basis. Finding counseling

to help mediate the influence of your parents' divorce on your

current marital relationship can also be helpful. If you are

married and things appear to hit a wall, consider counseling,

consulting with other couples, and reading self-help books. Often

the insurmountable walls that couples face in marriage slowly

collapse with time and concerted effort.

Years ago, a colleague and I wrote a self-assessment to help

students identify the personal divorce risks so that they could

strategize what to do when faced with those risks. Take 10 minutes

and learn what you can about your own divorce risks. (also take the

time to watch another example of the Sociological Imagination in

the case of W. E. B. Du Bois below).

Divorce

Risks Assessment Questionaire PDF

One last note about the Sociological Imagination. One of my

personal heroes is W.E.B. Du Bois. He was the first black Harvard

Graduate, the first to scientifically analyze U.S. blacks (See The

Philadelphia Negro), and one of the most prolific Sociological

writers ever. Watch my short lecture video on how the Sociological

Imagination helps us to understand the personal lives of this hero,

and think about the tragedy that could have been had he grown up in

the U.S. Southern states instead of in Massachusetts.

(see Center for Disease

Control “First Marriage Dissolution, Divorce, and Remarriage:

United States taken from Internet 5 July, 2008 from

(see Center for Disease

Control “First Marriage Dissolution, Divorce, and Remarriage:

United States taken from Internet 5 July, 2008 from