6.1: Gender

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 189360

- Erika Goerling & Emerson Wolfe

- Portland Community College via OpenOregon

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Analyze the impact of colonization upon indigenous traditional practices regarding gender and social structures

- Discuss decolonization and current activism that seek to return to pre-colonial understandings of gender as a basis for intergenerational healing

- Explore gender as a social construct by looking at many perspectives around the world

- Describe gender variations

- Explain how various socialization agents (e.g., parents, peers, schools, textbooks, television and religion) contribute to the formation of gender roles

- Compare psychological theories on gender

- Create a plan to be an ally to others to promote individual and community well-being

Introduction

Sex and gender are often confused for one another and are used interchangeably in many circumstances; however, these are distinct concepts. Sex, like we explored last week, depends on chromosomes, genetics, hormones, hormone receptors, gonads, and epigenetic factors, and secondary sex characteristics continue to unfold during puberty and throughout our lifespans impacting the way that our physical bodies look and feel. Female, intersex, and male bodies exist on a continuum of possibilities. Gender, on the other hand, is a social construct based on gender roles, expectations around behavior, stereotypes concerning vague concepts like femininity and masculinity, and personal internalization of what gender means to each individual person. All of these factors, through socialization, work to influence the way each individual person internalizes concepts around gender.

Some people will conform to what is socially expected of them based on the way others have labeled their gender while others will identify differently and carve out a different path. Additionally, humans do not remain stagnant and gender can also change throughout a person’s lifetime depending on life experiences, education, exposure to differing perspectives, religious upbringing, family background, peer interactions, media, and more. Before we can delve into this topic more globally, let’s first look at gender in the United States. Then, we will analyze multicultural perspectives to highlight how gender can take on different meanings based on culture and society, we will explore theories around gender, and we will analyze the way in which this culminates in the unique way each person will come to perceive gender and behave based on the internalization of gendered concepts. In order to explore where to go from here, we will discuss ways to be allies to all genders in order to build a healthy and sustainable future.

Gender and the United States

Gender expansive ideas are not new. Many indigenous communities in the United States have long held places of high esteem for those who can move more fluidly between roles. Being able to walk between the worlds of gender also holds spiritual significance and strength. Creating a binary system for gender has always been about power and control, and this is a tool utilized to uphold white supremacy, the patriarchy, and further colonial domination. Religion, namely Christianity and Catholicism, were wielded as swords, not of justice but of genocide and apartheid. In order to understand the ways in which gender is a social construct, let’s take a deep dive into US colonization to lead us to this present moment in time. The past is still present in many ways. Decolonizing and indigenizing views on gender can be sources of healing and empowerment.

Indigenous Perspectives

Native Americans and Alaskan Natives

The Secretariat of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UN Forum) (2010) explains that, prior to colonization, indigenous women, men, and intersex individuals held equitable social statuses and were stewards of the land and resources in partnership with each other. The UN Forum (2010) discusses how many indigenous communities thrived off of the concept of generalized reciprocity in which repayment was not expected and rather a sense of generosity and the continual sharing of resources was expected instead. Thus, the concept of property and ownership rights were not present to reinforce gender segregation or differences. Many indigenous communities also relied on symbiotic complementarily which is a means of producing resources in a way that recognizes the need for differentiation in the labor force without one type of role dominating the other or taking on more social importance than another (UN Forum, 2010).

Two-spirit and gender-expansive perspectives have also been documented within many traditional tribal societies. According to Indian Health Service (n.d.), Native American and Alaskan Native tribes, in general, had a more gender-expansive view with many tribes denoting a third or even fourth gender category in which individuals were respected and valued as they took on activities for both women and men and even had specialized roles as spiritual guides, healers, shamans, artists, and more. Some two-spirit individuals would take on a traditional male or female style of dress depending on how they identified while others developed their own ways of self-expression (Indian Health Service, n.d.).

More than 500 indigenous cultures have survived cultural genocide in the United States (Indian Health Service, n.d.) with some preferring the use of specific terms within their language rather than the use of the recently developed term of two-spirit. Two-spirit is a term in English or referred to as a “pan-Indian” word created in the 1990s by an international gathering of indigenous tribes to replace the colonizer word “berdache” which has a harmful connotation and is related to sex acts rather than gender (Matthews-Hartwell, 2014). Many tribes prefer to use the terms in their language rather than using the term two-spirit. Here are some examples of tribal terms (Matthews-Hartwell, 2014):

- Navajo: Nádleehí and Dilbaa’

- Lakota: Winkte

- Zuni: Lhamana

- Osage: Mixu’ga

- Ojibwa: Agokwa and Ogichidaakwe

Native American and Alaskan Native cultures are not monolithic and contain many nuances and differences in practices as well. Thus, it is important to not generalize the concept of two-spirit to all tribal communities by understanding the diverse cultural practices and customs of individual tribes as well as individual people who are tribal members.

Further firsthand accounts by tribal members:

- Native American ‘Two-Spirit People’ Serve Unique Roles Within Their Communities: One ‘Winkte’ Talks About Role Of LGBT People In Lakota Culture (Wisconsin Public Radio, 2014)

-

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/introtohumansexuality/?p=58#oembed-1

- Not shown in the captioning: Ma-Nee Chacaby mentions identifying as the Anishinaabeg term Niizhojichaagwijig-meaning “ones with two spirits” (Native Justice Coalition, 2020).

Native Hawaiian Perspective

Māhū is a Native Hawaiian third gender that indicates someone who has qualities of both kāne (man) and wahine (woman) (University of Hawai’i, Manoa, 2021). Māhūkāne is another variation of the term māhū which means a wahine who lives his life as a kāne, and māhūwahine which means a kāne who lives her life as a wahine (University of Hawai’i, Manoa, 2021). These terms are not exactly comparable to terms such as transgender or nonbinary because they are specific within Native Hawaiian culture, and individuals with these identities held significant spiritual and cultural importance within pre-colonial life. These identities were nearly erased through colonization and religious demonization but have begun to regain a place of prominence and respect as kānaka maoli (Native Hawaiians) are seeking to reconnect with traditional cultural practices and heal their communities.

The concept of ho’okipa, translated roughly to hospitality, was an important part of traditional Hawaiian culture that was exploited by sailors, missionaries, and businessmen, and continues to be used as justification for overtourism today (Sustainable Tourism Study Native Hawaiian Advisory Group, 2003, p. I-2). “The patriarchal sexualization of islands and their peoples provides justification for continued colonial protection” in the form of economic and governmental control by those who are not kānaka maoli (Na’puti & Rohrer, 2017, p. 543). The Hawaiian islands and people remain exotified today through tourism which reduces women specifically to sexualized, beautiful objects to be consumed by outside visitors (Na’puti & Rohrer, 2017). Over-tourism taxes the people and the land, leading to further marginalization of kānaka maoli (Sustainable Tourism Study Native Hawaiian Advisory Group, 2003, p. I-1).

Videos from the Kumu Hina Project which seek to increase awareness of pre-colonial Native Hawaiian culture and recenter individuals who are māhū as vital to the community:

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/introtohumansexuality/?p=58#oembed-2

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/introtohumansexuality/?p=58#oembed-3

Influence of Colonization on Indigenous Peoples

Cultural genocide was inflicted upon Native communities through the death of tribal members as a result of violence and disease (Indian Health Service, n.d.). Native children were placed in boarding schools controlled by white settlers, missionaries, and governmental agencies, which resulted in the loss of Native cultural traditions and perspectives regarding gender (Indian Health Service, n.d.). The UN Forum (2010) explains how colonization imposed gender segregation and unequal power by dictating that men would control resources and thereby reduced the social status of tribal women which worked to deprive them of access to resources and land rights that they previously held equally. This also fractured the stability of communities and worked to erase indigenous traditions to further weaken the interconnectivity of tribal members (UN Forum, 2010). Two-spirit identities were targeted with particular violence and malice, which has resulted in the erasure of many gender-variant traditions that descendants of tribal communities are still trying to uncover, retrace and decolonize today (Indian Health Service, n.d.).

Spillett (2021) explains that the forceful internment of Native peoples by colonizers who imposed a gender binary and heteronormative relationship norms was leveled as a specific means to dislocate people from their tribal lands and take control over tribal resources. Gendered physical and sexual violence is a particular tool repeatedly used during colonization to target indigenous women and individuals with gender-expansive identities to tear apart their social support networks, sense of self, and cultural power in order to gain control (Spillett, 2021). This demoralization process is at the heart of taking over the land (Spillett, 2021). Puritanical or Catholic ideas around what constituted sin, impropriety, impurity, and sickness were used to further glorify and support the subjugation of traditional indigenous cultures and to impose religious perspectives. Manifest Destiny, the idea that it was God’s will for man to rule the Earth and dominate nature, connected colonization with furthering the patriarchy and male settler rule over Native communities who they othered and viewed as part of nature (Spillett, 2021).

Foundations of Gendered Violence Lie within White Supremacy

African people engaged in diverse relational and social practices prior to being stolen from their homeland and brought to the Americas (Amadiume, 2001). Some communities held more patriarchal social stratification while a majority were more matriarchal with the women being highly respected and looked to as leaders of their family units and communities (Amadiume, 2001). European analyses of African culture utilized an ethnocentric perspective that prescribed patriarchy as a means of salvation when in reality it sought to destroy the social relations and strength found within family units (Amadiume, 2001). The slavery of African people in the United States furthered the impact of colonization and displaced people from their homelands, families, and cultural traditions. Families were separated and violence was commonplace in order to maintain systems of power that favored white settlers as masters over Black people.

African men were often displaced and separated from their families with mothers and children remaining together until the children reached a certain age to be sold for their labor as well. Women often faced additional sexual violence and their reproductive freedoms were taken away from them as well as their ability to be in romantic relationships without the say of their masters. Castration was a means of punishment for some enslaved men and a preoccupation with Black male masculinity and sexuality was viewed from behind the lens of impurity and criminality (Mack & McCann, 2018). Black women were viewed as overly sexual in order to blame them for the sexual violence that was inflicted upon them (Mack & McCann, 2018).

As slavery was outlawed and slaves were freed, the Ku Klux Klan still terrorized Black people and sought to criminalize male bodies and further disenfranchise Black women and separate family units from one another (Mack & McCann, 2018). Labeling Black men as hypersexual and sexual aggressors allowed white men to justify their violence as a means of protecting white women (Mach & McCann, 2018). Thus, gendered violence and the intersection of race and gender shaped the experiences of Black people and still do to this day as Black men face being labeled criminals and sexual deviants facing harsher prison sentences while Black women are labeled as hypersexual with their sexuality needing to be limited and controlled within the modern-day white supremacist, patriarchal and colonial society (Mack & McCann, 2018). Black transgender women face violence and discrimination at even higher rates than Black cisgender women; thus, intersectionality is key to understanding these interlocking systems impacting the lives of individuals.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/introtohumansexuality/?p=58#oembed-4

Roles of Systems: Two Examples

Boarding Schools (Education System)

The boarding school system in the United States was first developed to assimilate and endoctriante Native American children into Christian, white supremacist, and patriarchal systems and to rid them of their culture. A binary system of gender was imposed and two-spirit cultural practices and beliefs were attempted to be destroyed. Physical and sexual abuse was rampant; thus, terrorism as a tool of colonization was inflicted upon Indigenous children and families within these schools.

Police Departments and the Origins of “Policing” (Legal System)

Modern police departments in many Southern states started out as “slave patrols.” For a more detailed look at the history of policing in the United States, review the information provided by Potter (2013). Race-based violence was sanctioned by the government in Southern states in order to maintain a racial and economic caste system with white people clinging to power through the use of violence and targeted attempts to destroy communities, physically, emotionally, and spiritually.

Anti-masquerading laws, prohibitions and ordinances were passed in the 1800s with some remaining on the books even until recently in some states, such as New York until 2011 (PBS, 2015). In order to attract more middle class white residents to frontier towns, police would use these legal measures to target individuals labeled as cross-dressers (Tagawa, 2015). “In Columbus, Ohio, where one of the earliest ordinances was instituted, an 1848 law forbade a person from appearing in public ‘in a dress not belonging to his or her sex.’ In the decades that followed, more than 40 U.S. cities created similar laws limiting the clothing people were allowed to wear in public” (PBS, 2015, para. 5). Up until 1974 in San Francisco, the city’s anti-masquerading law was used to target men who dressed as women (Tagawa, 2015). The police would also enforce the measures inconsistently, specifically targeting communities deemed more problematic for the city or to use the legal cover to harass specific nonbinary and transgender communities (Tagawa, 2015). In thinking about intersectionality, BIPOC individuals who are also gender nonconforming, transgender and gender expansive receive additional scrunity from police at the intersection of race and gender.

Conformity as a Trauma Response to Systemic Isms

Conformity happens all the time and is used by people subconsciously in order to better fit in with the crowd. When we are cast out, this leads to further marginalization and stigmatization. Humans are social creatures, so we will sometimes sacrifice parts of ourselves in order to more easily fit in with others, especially when the harms to not conform are so great. Terrorism and forced assimilation have long been tactics used by colonizers, and this remains a tool used today by the powerful in various ways. Trauma is tied to nonconformity (religion, race, gender, etc.) within a Christian, white supremacist, patriarchal, and capitalistic society, and people may begin to have prejudices that go against their own cultural and ancestral knowledge in order to conform to these systems. Therefore, these traumatic experiences around identities based on social constructs and caste systems work to speed up assimilation and conformity by fragmenting the spiritual, emotional, and physical parts of a person in order to break them apart from their sense of community and interconnection with others.

Intersectionality and Resiliency

In a white supremacist society, being BIPOC (Black, Biracial, Indigenous, or a Person of Color) alone as an identity causes the individual to face potentially daily microaggressions. In a white supremacist and patriarchal society, being BIPOC and a cisgender female adds another layer to the systemic and social barriers faced. Adding on now again, being BIPOC and a transgender female will lead to even more specfic social struggles that are incurred by not conforming. Therefore, nonconforming should be viewed as a testament to the human spirit and the desire of people to remain whole and not ripped apart from their identities. In the face of trauma and terror, communities continue to rise. Solidarity and being co-conspirators in the liberation of each other leads to community wellbeing and healing.

Decolonization and Intergenerational Healing

Many people of Indigenous and African ancestry are seeking to reconnect and reclaim identities and cultural perspectives that were attempted to be erased through colonization and land displacement. Oral traditions and the sharing of knowledge amongst families and friends passed down for generations have allowed for the current decolonization of gender to take place as a means of healing. Looking at how BIPOC identities intersect with gender specifically allows for an intersectional perspective to reconstruct a new path forward. Additionally, with social movements such as #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, and the Indigenous Peoples Movement to name a few, social discourse is changing around gender and moving more toward women’s rights to live without sexual harassment and assault as well as looking at gender as existing within a spectrum of possibilities rather than within binary systems. Social structures are shifting as activists and scholars are identifying the negative impacts of patriarchal, binary, and heteronormative perspectives.

Indigenous communities starting in Canada and now in the United States are urging both governments to conduct reports and issue formal statements about the abuse in general at the boarding schools and the ways in which this abuse caused the death of Indigenous children and adults. As of May 8th, 2022, the U.S. Department of the Interior released an investigative report and next steps related to the boarding schools. The following is taken directly from the report:

The investigation found that from 1819 to 1969, the federal Indian boarding school

system consisted of 408 federal schools across 37 states or then territories, including 21

schools in Alaska and 7 schools in Hawaii. The investigation identified marked or

unmarked burial sites at approximately 53 different schools across the school system.

As the investigation continues, the Department expects the number of identified burial

sites to increase.

“The consequences of federal Indian boarding school policies—including the

intergenerational trauma caused by the family separation and cultural eradication

inflicted upon generations of children as young as 4 years old—are heartbreaking and

undeniable,” said Secretary Haaland. “We continue to see the evidence of this attempt

to forcibly assimilate Indigenous people in the disparities that communities face. It is my

priority to not only give voice to the survivors and descendants of federal Indian boarding

school policies, but also to address the lasting legacies of these policies so Indigenous

peoples can continue to grow and heal.”

Intergenerational Healing: Research Snapshots from Within Communities

Reclaiming Our Voices

In the interviews conducted with two-spirit Native individuals, Frazer and Pruden (2010) found that many expressed the desire for cultural programming that affirmed both their Native and two-spirit identities. Substance use was of great concern regarding engaging in queer nightlife that could affirm their gender expansive identity because many either had personal or familial struggles with addiction while cultural programming and events often excluded two-spirit self-expression–they did not feel like they could be their full selves in either environment. A majority of the participants expressed experiencing bullying and harassment from other tribal members and explained that informing people of pre-colonial practices around gender would be helpful in reducing the stigma and shame (Frazer & Pruden, 2010). Mental health and substance use programs that affirmed both their Native culture and two-spirit identities were identified as lacking and needed.

Emotional Emancipation Circles

Intergenerational trauma, in which harms of the past are passed down from generation to generation in the form of trauma stories, reactivity to environmental stressors, and the compounding impacts of minority stress leading to trauma symptoms in caregivers that is modeled for younger individuals within a family unit, has long been the focus of researchers (Fishbane, 2019). However, recently, a shift toward exploring the healing process has begun in order to center and honor the work that is being done within families and communities to create a new path forward (Fishbane, 2019). The injustices, genocide, and cultural erasure of colonization are called out and addressed while new systems and interconnections are created anew.

Barlow (2018) explores how her use of Emotional Emancipation Circles (EECs) is designed to be a strengths-based and culturally responsive approach to healing. Barlow (2018) explains how she used (EECs) with college students:

“This approach does not represent neoliberal frameworks of a thriving individual. Instead, it harmonizes and coordinates the well-being of people of African descent who are living with the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, and white supremacy in the US. With learning modules, called keys, dedicated to African culture, history and movements, and imperatives and ethics, this social support group offered my students an opportunity to unpack personal stories and to begin to address the root issues of healing Black communities.

For example, students shared their struggles with colorism, the social rules of dating, navigating social media, thriving in the classroom, and managing challenges at home while in college. (p. 900)

By sharing these stories and supporting each other, they were able to develop social support as a protective factor (Barlow, 2018). Barlow (2018) also discusses how increasing self-care in the form of “meditation, breathing exercises, and physical activity such as walking, dancing, running, and gardening” are beneficial to physical and mental health (p. 901). Engaging in self-care and developing social support systems were encouraged. Barlow (2018) also encouraged her students to share their experiences of intergenerational trauma and healing through social media. By sharing their experiences, further connections were made and students developed skills on how to mobilize their communities and be leaders promoting social change within organizations (Barlow, 2018). Thus, individuals engaging in their own healing are able to model this for others, creating community-based healing that expands onward.

Further Decolonization and Intergenerational Healing Resources

- Celebrating Our Magic: Resources for American Indian/Alaska Native transgender and Two-Spirit youth, their relatives and families, and their healthcare providers

- Trans Care BC: Two-Spirit

- Lots of resources to both explore one’s clinical practice and to learn more about two-spirit and indigenous LGBTQIA+ experiences as well as resources for clients.

- From Canada but does include United States-based information.

- First Nations Perspective on Health and Wellness

- This poster can be used to discuss strengths and protective factors with Indigenous gender expansive clients.

- Research Article: Jefferson et al. (2013) found that a strong transgender identity served as a protective factor against depression for transgender women of color.

- Identity should be explored in a strength-based way with clients. Keep this in mind from an intersectional approach.

- Research Article: Baez, M. S. E., Isaac, P., & Baez, C. A. (2016). H.O.P.E. for Indigenous people battling intergenerational trauma: The Sweetgrass Method. Journal of Indigenous Research, 5(2). Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1055&context=kicjir

Multicultural Perspectives

Mestiza Consciousness

In her seminal text Borderlands La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987), Gloria Anzaldúa moves away from masculinist, heterosexist, nationalist, and biological notions of mestizaje attributing new meaning to identity construction through her concept of “mestiza consciousness”—one that emerges from life in the Borderlands (for more on Borderlands studies visit Section 3.1: What is Chicanx/Latinx History). Mestiza consciousness is a cognitive decolonization process of racialized, gendered, and sexed subjects wherein la mestiza becomes aware of the Borderlands and makes conscious decisions regarding the construction of her multiple and often contradictory identities. Through mestiza consciousness––later conceptualized as “conocimiento”––la nueva mestiza rethinks her material, psychic, and spiritual existence as she negotiates contradictions and ambiguities as a subject-in-process who is constantly constructing provisional identities.

AnaLouise Keating, feminist scholar and editor of Anzaldúa’s work, succinctly describes Anzaldúa’s theory of the new mestiza as “an innovative expansion of previous biologically based definitions of mestizaje. For Anzaldúa, new mestizas are people who inhabit multiple worlds because of their gender, sexuality, color, class, bodies, personality, spiritual beliefs, and/or other life experiences. This theory offers a new concept of personhood that synergistically combines apparently contradictory Euro-American and Indigenous traditions." (Keating, 2009 pg. 322)

Xicanisma

Chicana feminists continued to intervene in Chicano nationalist constructions of Indigeneity by unsettling myths and binaries that were delineated during El Movimiento through Xicanisma, an embodied feminist philosophy and praxis. “During the 1990s a cohort of Chicana feminists began replacing the Ch in ‘Chicana’ with a capital X (Xicana) in order to summon the lexical appearance––and sound––of Nahuatl, an ancient but still living Indigenous language. …Contemporary Xicana feminist sonic, lexical, and political replacements of the Ch with an X are meant to point to Indigenous uprisings within and throughout Chicana, Chicano, and Chicanx identities. Today, the spoken and written grapheme X acts as a mobile signifier that points to identities-in-redefinition." (Sandoval et al., n.d.)

Castillo (1994) introduces the term Xicanisma, a retrofitted form of Chicana feminism intended to create an avenue for mestizas and detribalized Indigenous women to “not only reclaim our Indigenismo––but also to reinsert the forsaken feminine into our consciousness." (p. 12.) In order to heal from historical, institutional, and personal traumas, Castillo advocates acknowledging and honoring the feminine side of our complementary feminine/masculine duality. To do this, she writes, would restore spiritual balance. This restorative act challenges U.S. white supremacy, Chicano heteropatriarchy, and the Catholic Church––all rely on stringent dichotomies that repress women’s spirituality and sexuality. Xicanisma is “an ever present consciousness of interdependency specifically rooted in our culture and history." (Castillo, 1994 p. 226.) Xicanisma is a practical way for retribalizing peoples of any gender to express an Indigenous sensibility, reconnect spirituality with the body/sexuality, and to (re)claim and (re)construct their traditions in a way that serves their present needs.

Similarly, Xicana lesbian activist and playwright Cherríe Moraga explains her use of the X indicates “a reemerging política, especially among young people, grounded in Indigenous American belief systems and identities... [that] reflects the Indian identity that has been robbed from us through colonization... As many Raza may not know their specific Indigenous nation of origin, the X links us as Native people in diaspora” (Moraga, 2011 pg. xxi). Moraga is co-founder of La Red Xicana Indígena, (The Indigenous Xicana Woman’s Network), along with Celia Herrera Rodríguez, a collective of scholar- and community-activists who define themselves as a network actively involved in political, educational, and cultural work that serves to raise indigenous consciousness among our communities and supports the social justice struggles of people of indigenous American origins North and South. Our name...further signifies our alliance with all Red Nations of the Américas, including nations residing in the North. We are a pueblo made up of many indigenous nations in diaspora who through a five hundred year project of colonization, neocolonization, and de-indianization, have been forced economically from their place of origin, many ending up in the United States… [W]e stand with little legal entitlement to our claim as indigenous peoples within America; however, we come together on the belief that, with neither land base nor enrollment card––like so many urban Indians in the North, and so many displaced and undocumented migrants coming from the South, we have the right to “right” ourselves.

The writers of this document further explain that Xicana Indígena politics re-envision “families apart from the Eurocentric model of the privatized patriarchal family,” and seek to “draw examples from the tribal structure of...indigenous antecedents.” Moraga, along with co-founder Celia Herrera Rodríguez, advocate for raising the consciousness of younger generations through alternative and creative learning environments that “closely reflect an indigenous point of view.” In sum, mestiza consciousness and Xicanisma are Ch/Xican/x feminist ontologies––philosophical explorations of the nature of being––grounded in a decolonial and liberatory praxis.

Footnotes

González, A. R. (2015). “Where is Indigeneity in Chican@ Studies?” in Another City is Possible: Mujeres de Maiz, Radical Indigenous Mestizaje and Activist Scholarship, PhD diss. University of California, Santa Barbara.

Keating, A. (2009) “Appendix 1. Glossary,” in The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Sandoval, C., González A. R., and Montes, F. (n.d.) Urban Xican/x-Indigenous Fashion Show ARTivism: Experimental Perform-Antics in Three Actos, in meXicana Fashions: Politics, Self-Adornment, and Identity Construction, eds. Aída Hurtado and Norma E. Cantú. University of Texas Press, 283-84.

Castillo, A. (1994) Massacre of the Dreamers: Essays on Xicanisma.

Moraga, C. (2011). A Xicana Codex of Changing Consciousness: Writings, 2000-2010. Duke University Press.

The Psychology of Gender

Introduction

Though typically considered synonyms by many, sex and gender have distinct meanings that become important when collecting data and engaging in research. First, sex refers to the biological aspects of a person due to their anatomy. This includes the individual’s hormones, chromosomes, body parts such as the sexual organs, and how they all interact. When we say sex, we are generally describing whether the person is male or female and this is assigned at birth.

In contrast, gender is socially constructed (presumed after a sex is assigned) and leads to labels such as masculinity or femininity and their related behaviors. People may declare themselves to be a man or woman, as having no gender, or falling on a continuum somewhere between man and woman. How so? According to genderspectrum.org, gender results from the complex interrelationship of three dimensions – body, identity, and social.

First, body, concerns our physical body, how we experience it, how society genders bodies, and the way in which others interact with us based on our body. The website states, “Bodies themselves are also gendered in the context of cultural expectations. Masculinity and femininity are equated with certain physical attributes, labeling us as more or less a man/woman based on the degree to which those attributes are present. This gendering of our bodies affects how we feel about ourselves and how others perceive and interact with us.”

Next is gender identity or our internal perception and expression of who we are as a person. It includes naming our gender, though this gender category may not match the sex we are assigned at birth. Gender identities can take on several forms from the traditional binary man-woman, to non-binary such as genderqueer or genderfluid, and ungendered or agender (i.e. genderless). Though gaining an understanding of what gender we are occurs by age four, naming it is complex and can evolve over time. As genderspectrum.org says, “Because we are provided with limited language for gender, it may take a person quite some time to discover, or create, the language that best communicates their internal experience. Likewise, as language evolves, a person’s name for their gender may also evolve. This does not mean their gender has changed, but rather that the words for it are shifting.”

Finally, we have a social gender or the manner in which we present our gender in the world, but also how other people, society, and culture affect our concept of gender. In terms of the former, we communicate our gender through our clothes, hairstyles, and behavior called gender expression. In terms of the latter, children are socialized as to what gender means from the day they are born and through toys, colors, and clothes. Who does this socialization? Anyone outside the child can to include parents, grandparents, siblings, teachers, the media, religious figures, friends, and the community. Generally, the binary male-female view of gender is communicated for which there are specific gender expectations and roles. According to genderspectrum.org, “Kids who don’t express themselves along binary gender lines are often rendered invisible or steered into a more binary gender presentation. Pressures to conform at home, mistreatment by peers in school, and condemnation by the broader society are just some of the struggles facing a child whose expression does not fall in line with the binary gender system.” The good news is that gender norms do change over time such as our culture’s acceptance of men wearing earrings and women getting tattoos.

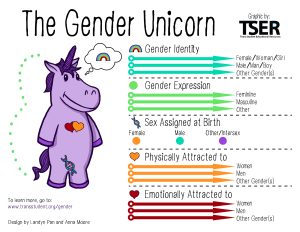

Here is a resource that is used within counseling and group therapy sessions to help people explore their experiences and identities. People are meant to mark themselves on every single line within each category. The first three categories relate to what we have been discussing so far while the last two relate to sexual orientation which we will discuss next week. Check out the developer’s website to see an explanation of relevant terms and how to fill out the Gender Unicorn worksheet.

Gender Congruence

When we feel a sense of harmony in our gender, we are said to have gender congruence. It takes the form of naming our gender such that it matches our internal sense of who we are, expressing ourselves through our clothing and activities, and being seen consistently by other people as we see ourselves. Congruence does not happen overnight but occurs throughout life as we explore, grow, and gain insight into ourselves. It is a simple process for some and complex for others, though all of us have a fundamental need to obtain gender congruence.

When a person moves from the traditional binary view of gender to transgender, agender, or non-binary, they are said to “transition” and find congruence in their gender. Genderspectrum.org adds, “What people see as a “Transition” is actually an alignment in one or more dimensions of the individual’s gender as they seek congruence across those dimensions. A transition is taking place, but it is often other people (parents and other family members, support professionals, employers, etc.) who are transitioning in how they see the individual’s gender, and not the person themselves. For the person, these changes are often less of a transition and more of an evolution.” Harmony is sought in various ways to include:

- Social – Changing one’s clothes, hairstyle, and name and/or pronouns

- Hormonal – Using hormone blockers or hormone therapy to bring about physical, mental, and/or emotional alignment

- Surgical – When gender-related physical traits are added, removed, or modified

- Legal – Changing one’s birth certificate or driver’s license

The website states that the transition experience is often a significant event in the person’s life. “A public declaration of some kind where an individual communicates to others that aspects of themselves are different than others have assumed, and that they are now living consistently with who they know themselves to be, can be an empowering and liberating experience (and moving to those who get to share that moment with them).”

Gender and Sexual Orientation

As gender was shown to be different from sex, so too we must distinguish it from sexual orientation which concerns who we are physically, emotionally, and/or romantically attracted to. Hence, sexual orientation is interpersonal while gender is personal. We would be mistaken to state that a boy who plays princess is gay or that a girl who wears boy’s clothing and has short hair is necessarily lesbian. The root of such errors comes from our confusing gender and sexual orientation. The way someone dresses or acts concerns gender expression and we cannot know what their sexual orientation is from these behaviors.

The Language of Gender

- Agender – When someone does not identify with a gender

- Cisgender – When a person’s gender identity matches their assigned sex at birth

- FtM – When a person is assigned a female sex at birth but whose gender identity is boy/man

- Gender dysphoria – When a person is unhappy or dissatisfied with their gender and can occur in relation to any dimension of gender. The person may experience mild discomfort to unbearable distress. This is classified as a mental health diagnosis and this diagnosis must be given to an individual in most states if they wish to receive hormone and other gender-affirming treatments. Not all transgender or nonbinary people may experience gender dysphoria and some cisgender people may experience this.

- Genderfluid – When a person’s gender changes over time; they view gender as dynamic and changing

- Gender role – All the activities, functions, and behaviors that are expected of males and females in a gender binary society

- Genderqueer – Someone who may not identify with conventional gender identities, roles, expectations, or expressions.

- MtF – When a person is assigned a male sex at birth but whose gender identity is girl/woman

- Non–binary – When a gender identity is not exclusively masculine or feminine

- Transgender – An umbrella term that denotes when a person’s gender identity differs from their assigned sex

To learn more about gender, we encourage you to explore the https://www.genderspectrum.org/ website.

The World Health Organization also identifies two more key concepts in relation to gender. Gender equality is “the absence of discrimination on the basis of a person’s sex in opportunities, the allocation of resources and benefits, or access to services” while gender equity refers to “the fairness and justice in the distribution of benefits and responsibilities between women and men.” Keep in mind, this language still caters to the gender binary and leaves out transgender and gender-expansive identities.

Gender Through a Developmental Psychology Lens

Psychoanalytical Theories

We have already previously discussed Freud, so let’s continue forward with Karen Horney’s Neo-Freudian theory.

Horney developed a Neo-Freudian theory of personality that recognized some points of Freud’s theory as acceptable, but also criticized his theory as being overly bias toward the male. There is truth in this if you think about Freud’s theory. Ultimately, to really develop fully, one must have a penis – according to Freud’s theory. A female can never “fully” resolve penis envy, and thus, she is never fully able to resolve the conflict. As such, according to Freud’s theory, if taken literally, a female can never fully resolve the core conflict of the Phallic Stage and will always have some fixation and thus, some maladaptive development. Horney disputed this (Harris, 2016). In fact, she went as far as to counter Freud’s penis envy with womb envy (a man envying a woman’s ability to have children). She theorized that men looked to compensate for their lack of ability to carry a child by succeeding in other areas of life (Psychodynamic and neo-Freudian theories, n.d.)

The center of Horney’s theory is that individuals need a safe and nurturing environment. If they are provided such, they will develop appropriately. However, if they are not, and experience an unsafe environment, or lack of love and caring, they will experience maladaptive development which will result in anxiety (Harris, 2016). An environment that is unsafe and results in abuse, neglect, stressful family dynamics, etc. is termed by Horney as basic evil. As mentioned, these types of experiences (basic evil) lead to maladaptive development which was theorized to occur because the individual began to believe that, if their parent did not love them then no one could love them. The pain that was produced from basic evil then led to basic hostility. Basic hostility was defined as the individual’s anger at their parents while experiencing high frustration that they must still rely on them and were dependent on them (Harris, 2016).

This basic evil and basic hostility ultimately led to anxiety. Anxiety resulted in an individual developing interpersonal strategies of defense (ways a person relates to others). These strategies are considered to fall in three categories (informed by Harris, 2016):

Interpersonal Strategies

| Interpersonal Strategy | Key Direction | Actions the Person Takes | How This Presents in Their Personalities |

| Compliant Solution | Toward | The individual moves toward people. They seek out another person’s attention. | This is the people pleaser and dependent person. The person that avoids failure and always takes the “safe” option. |

| Detachment Solution | Away | These individuals move away from others and attempt to protect themselves by eluding connection and contact with others. | These individuals want independence and struggle with commitment. They often try to hide flaws |

| Expansive Solution | Against | These individuals move against others. They seek interaction with others, not to connect with them, rather to gain something from them. They seek power and admiration from others, as well as being seen as highly attention-seeking. | This category is further split into three types of individuals:

1. The Narcissist. 2. The Perfectionist. 3. The Arrogant-Vindictive person. |

Although Horney disputed much of Freud’s male biased theories, she recognized that females are born into a society dominated by males. As such, she recognized that females may be limited due to this, which then leads to developing a masculinity complex. This is the feeling of inferiority due to one’s sex. She noted that one’s family can strongly influence one’s development (or lack thereof) of this complex. She described that if a female was disappointed by males in her family (such as their father or brother, etc.), or if they were overly threatened by females in their family (especially their mothers), they may actually develop contempt for their own gender. She also indicated that if females perceived that they had lost the love of their father to another woman (often to the mother) then the individual may become more insecure. This insecurity then would lead to either (1) withdrawal from competing or (2) becoming more competitive (Harris, 2016). The need for the male attention was referred to as the overvaluation of love (Harris, 2016).

Gender Socialization Theory

It’s clear that even very early theories of gender development recognized the importance of environmental or familial influence, at least to some degree. As theories have expanded, it has become clearer that socialization of gender occurs. However, each theory has a slightly different perspective on how that may occur. We will discuss a few of those in brief detail, but will focus more on major concepts and generally accepted processes.

Before we get started, I want you to ask yourself a few questions – When do we begin to recognize and label ourselves as boy or girl, and why? Do you think it happens very young? Is it the same across countries? Let’s answer some of those questions.

Theories that suggest that gender identity development is universal across countries and cultures (e.g., Eastern versus Western cultures, etc.) have been scrutinized. Critics suggest that, although biology may play some role in gender identity development, the environmental and social factors are perhaps more powerful in most developmental areas, and gender identity development is no different. It is the same “nature versus nurture” debate that falls on the common response of both nature and nurture playing important roles and to ignore one is a misunderstanding of the developmental process (Magnusson & Marecek, 2012). In this section, we are going to focus on the social, environmental, and cultural aspects of gender identity development

Early Life

Infants do not prefer gendered toys (Bussey, 2014). However, by age 2, they show preferences. (Servin, Bhlin, & Berlin, 1999). Did you know that infants can differentiate between male and female faces and voices in their first year of life (typically between 6-12 months of age; Fagan, 1976; Miller, 1983)? Not only that, they can pair male and female voices with male and female faces (known as intermodal gender knowledge; Poulin-Dubois, Serbin, Kenyon, & Derbyshire, 1994). Think about that for a moment – infants are recognizing and matching gender before they can ever talk! Further, 18-month old babies associated bears, hammers, and trees with males. By age 2, children use words like “boy” and “girl” correctly (Leinbach & Fagot, 1986) and can accurately point to a male or female when hearing a gender label given. It appears that children first learn to label others’ gender, then their own. The next step is learning that there are shared qualities and behaviors for each gender (Bussey, 2014).

By a child’s second year of life, children begin to display knowledge of gender stereotypes. Research has found this to be true in preverbal children (Fagot, 1974), which is really incredible, if you think about it. After an infant has been shown a gendered item (doll versus a truck) they will then stare at a photograph of the “matching gender” longer. So, if shown a doll, they will then look at a photograph of a girl, rather than a boy, for longer (when shown photographs of both a boy and girl side by side). This is specifically true for girls as young as 18-24 months; however, boys do not show this quite as early (Serbin,Poulin-Dubois, Colburne, Sen, & Eichstedt, 2001). Although interpretations and adherence to gender stereotypes is very rigid, initially, as children get older, they learn more about stereotypes and that gender stereotypes are flexible and varied. We actually notice a curved pattern in how rigid children are to stereotyped gender behaviors and expectations (Bussey, 2014). Initially, children are very rigid in stereotypes and stereotyped play. As they reach middle childhood, they become more flexible. However, in adolescents, they become more rigid again. And, generally, boys are more rigid and girls are more flexible with gender stereotypes, comparatively (Blakemore et al., 2009).

There are many factors that may lead to the patterns we see in gender socialization. Let’s look at a few of those factors and influencers.

Parents

Parents begin to socialize children to gender long before they can label their own. Think about the first moment someone says they are pregnant. One of the first questions is “How far along are you?” and then “Are you going to find out the sex of the baby?” We begin to socialize children to gender before they are even born! We pick out boy and girl names, we choose particular colors for nurseries, types of clothing, and decor, all based on a child’s gender, often before they are ever born (Bussey, 2014). The infant is born into a gendered world! We don’t really give infants a chance to develop their own preferences – parents and the caregivers in their life do that for them, immediately. Parents even respond to a child differently, based on their gender. For example, in a study in which adults observed an infant that was crying, adults described the infant to be scared or afraid when they were told the infant was a girl. However, they described the baby as angry or irritable when told the infant was a boy. Moreover, parents tend to reinforce independence in boys, but dependence in girls. They also overestimate their sons’ abilities and underestimate their daughters’ abilities. Research has also revealed that prosocial behaviors are encouraged more in girls, than boys (Garcia & Guzman, 2017).

Parents label gender even when not required. When observing a parent reading a book to their child, Gelman, Taylor, & Nguyen (2004) noted that parents used generic expressions that generalized one outcome/trait to all individuals of a gender, during the story. For example, “Most girls don’t like trucks.” Essentially, parents provided extra commentary in the story, and that commentary tended to include vast generalizations about gender. Initially, mothers engaged in this behavior more than the children did; however, as children aged, children began displaying this behavior more than their mothers did. Essentially, mothers modeled this behavior, and children later began to enact the same behavior. Further, as children got older, mothers then affirmed children’s gender generalization statements when made.

Boys are more gender-typed and fathers place more focus on this (Bvunzawabaya, 2017). As children develop, parents tend to also continue gender-norm expectations. For example, boys are encouraged to play outside (cars, sports, balls) and build (Legos, blocks), etc. and girls are encouraged to play in ways that develop housekeeping skills (dolls, kitchen sets; Bussey, 2014). What parents talk to their children about is different based on gender as well. For example, they may talk to daughters more about emotions and have more empathic conversations, whereas they may have more knowledge and science-based conversations with boys (Bussey, 2014).

Parental expectations can have significant impacts on a child’s own beliefs and outcomes including psychological adjustment, educational achievement, and financial success (Bvunzawabaya, 2017). When parents approach more gender-equal or neutral interactions, research shows positive outcomes (Bussey, 2014). For example, girls did better academically if their parents took this approach versus very gender-traditional families.

Peers

Peers are strong influences regarding gender and how children play. As children get older, peers become increasingly influential. In early childhood, peers are pretty direct about guiding gender-typical behaviors. As children get older, their corrective feedback becomes subtler. So how do peers socialize gender? Well, non-conforming gender behavior (e.g., boys playing with dolls, girls playing with trucks) is often ridiculed by peers and children may even be actively excluded. This then influences the child to conform more to gender-traditional expectations (e.g., boy stops playing with a doll and picks up the truck).

We begin to see boys and girls segregate in their play, based on gender, in very early years. Children tend to play in sex-segregated peer groups. We notice that girls prefer to play in pairs while boys prefer larger group play. Boys also tend to use more threats and physical force whereas girls do not prefer this type of play. Thus, there are natural reasons to not intertwine and to instead segregate (Bussey, 2014). The more a child plays with same-gender peers, the more their behavior becomes gender-stereotyped. By age 3, peers will reinforce one another for engaging in what is considered to be gender-typed or gender-expected play. Likewise, they will criticize, and perhaps even reject a peer, when a peer engages in play that is inconsistent with gender expectations. Moreover, boys tend to be very unforgiving and intolerant of nonconforming gender play (Fagot, 1984).

Media and Advertising

Media includes movies, television, cartoons, commercials, and print media (e.g., newspapers, magazines). In general, media tends to portray males as more direct, assertive, muscular, in authority roles, and employed, whereas women tend to be portrayed as dependent, emotional, low in status, in the home rather than employed, and their appearance is often a focus. Even Disney movies tend to portray stereotyped roles for gender, often having a female in distress that needs to be saved by a male hero; although Disney has made some attempts to show women as more independent and assertive in more characters. We have seen a slight shift in this in many media forms, although it is still very prevalent, that began to occur in the mid to late 1980s and 1990s (Stever, 2017; Torino, 2017). This is important, because we know that the more children watch TV, the more gender stereotypical beliefs they have (Durkin & Nugent, 1998; Kimball 1986).

Moreover, when considering print media, we know that there tends to be a focus on appearance, body image, and relationships for teenage girls, whereas print media tends to focus on occupations and hobbies for boys. Even video games have gender stereotyped focuses. Females in video games tend to be sexualized and males are portrayed as aggressive (Stever, 2017; Torino, 2017).

School Influences

Research tends to indicate that teachers place a heavier focus, in general, on males – this means they not only get more praise, they also receive more correction and criticism (Simpson & Erickson, 1983). Teachers also tend to praise boys and girls for different behaviors. For example, boys are praised more for their educational successes (e.g., grades, skill acquisition) whereas girls are acknowledged for more domesticate-related qualities such as having a tidy work area (Eccles, 1987). Overall, teachers place less emphasis on girls’ academic accomplishments and focus more on their cooperation, cleanliness, obedience, and quiet/passive play. Boys, however, are encouraged to be more active, and there is certainly more of a focus on academic achievements (Torino, 2017).

The focus teachers and educators have on different qualities may have a lasting impact on children. For example, in adolescence, boys tend to be more career focused whereas girls are focused on relationships (again, this aligns with the emphasis we see placed by educators on children based on their gender). Girls may also be oriented toward relationships and their appearance rather than careers and academic goals, if they are very closely identifying with traditional gender roles. They are more likely to avoid STEM-focused classes, whereas boys seek out STEM classes (more frequently than girls). This may then impact major choices if girls go to college, as they may not have experiences in STEM to foster STEM related majors (Torino, 2017). As such, the focus educators place on children can have lasting impacts. Although we are focusing on the negative, think about what could happen if we saw a shift in that focus!

Okay, so we talked above about how children are socialized to gender – but how? Well there are a few areas we should discuss. We will cover social theories, cognitive theories, social cognitive theories, and biological theories.

Social Theories

Social Learning Theory

Do you remember Albert Bandura from Introduction to Psychology? He’s the guy that had children watch others act aggressively toward a doll (the BoBo doll), and then observed children’s behaviors with the same doll. Children that watched aggressive acts then engaged in aggression with the doll. Essentially, a behavior was modeled, and then they displayed the behavior. Here is a video with Albert Bandura and footage from his experiment:

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/introtohumansexuality/?p=58#oembed-6

Let’s think about this in a current-life example. You walk into a gym for the first time. It is full of equipment you aren’t sure how to use. What do you do if you want to know how to use it (let’s assume the nice little instructions with pictures are not posted on the equipment)? The most likely thing, if there is no trainer/employee around to ask, is to watch what someone does on the machine. You watch what how they set it up, what they do, etc. You then go to the equipment and do the same exact thing! This is modeling. You modeled the behavior the person ahead of you did. The same thing can happen with gender – modeling applies to gender socialization.

We receive much of our information about gender from models in our environment (think about all the factors we just learned about – parents, media, school, peers). If a little girl is playing with a truck and looks over and sees three girls playing with dolls, she may put the truck down and play with the dolls. If a boy sees his dad always doing lawn work, he may too try to mimic this, in the immediacy. Here is the interesting part: modeling does just stop after the immediate moment is over. The more we see it, the more it becomes a part of our socialization. We begin to learn rules of how we are to act and what behavior is accepted and desired by others, what is not, etc. Then we engage in those behaviors. We then become models for others as well! Now, some theories question modeling; although, further research has shown that modeling appears to be imperative in development, but the level of specificity or rigidity to gender norms of the behavior being modeled is also important (Perry & Bussey, 1979). Other’s incorporate modeling into their theory with some caveats. Kohlberg is one of those theorists, and we will learn about later.

Social Cognitive Theory

Another theory combines the theory of social learning with cognitive theories (we will discuss cognitive theories below). While modeling in social learning explains some things, it does not explain everything. This is because we don’t just model behavior, we also monitor how others react to our behaviors. For example, if a little girl is playing with a truck her peers laugh at her, that is feedback that her behavior is not gender-normative and she then may change the behavior she engages in. We also get direct instruction on how to behave as well. Again, girls don’t sit with their legs open, boys don’t play with dolls, girls don’t get muddy and dirty, boys don’t cry – you get the point. When peers or adults directly instruct another on what a girl or boy is or is not to do, although not modeling, is a heavily influential socializing factor. To explain this, social cognitive theory posits that one has enactive experiences (this is essentially when a person receives reactions to gendered behavior), direct instruction (this is when someone is taught knowledge of expected gendered behavior), and modeling (this is when others show someone gendered behavior and expectations). This theory posits that these social influences impact children’s development of gender understanding and identity (Bussey, 2014). Social cognitive theories of gender development explain and theorize that development is dually influenced by (1) biology and (2) the environment. Moreover, the theory suggests that these things impact and interact with various factors (Bussey & Bandura, 2005). This theory also accounts for the entire lifespan when considering development, which is drastically different than earlier theories, such as psychodynamic theories.

Cognitive Theories

Kohlberg’s Cognitive Developmental Theory

Lawrence Kohlberg theorized the first cognitive developmental theory. He theorized that children actively seek out information about their environment. This is important because it places children as an active agent in their socialization. According to cognitive developmental theory, a major component of gender socialization occurs by children recognizing that gender is constant and does not change which is referred to this as “gender constancy”. Kohlberg indicated that children choose various behaviors that align with their gender and match cultural stereotypes and expectations. Gender constancy includes multiple parts. One must have an ability to label their own identity which is known as gender identity. Moreover, an individual must recognize that gender remains constant over time which is gender stability and across settings which is gender consistency. Gender identity appears to be established by around age three and gender constancy appears to be established somewhere between the ages of five and seven. Although Kohlberg’s theory captures important aspects, it fails to recognize things such as how gender identity regulates gender conduct and how much one adheres to gender roles through their life (Bussey, 2014).

Although Kohlberg indicated that modeling was important and relevant, he posited that it was only relevant once gender constancy is achieved. He theorized that constancy happens first, which then allows for modeling to occur later (although the opposite is considered true in social cognitive theory). The problem with his theory is children begin to recognize gender and model gender behaviors before they have cognitive capacities for gender constancy (remember all that we learned about how infants show gender-based knowledge?!).

Gender Schema Theory

Gender schema theory, although largely a cognitive theory, does incorporate some elements of social learning as well. Schemas are essentially outlines – cognitive templates that we follow, if you will. Thus, a gender schema is an outline about genders – a template to follow regarding gender. The idea is that we use schemas about gender to guide our behaviors and actions. Within this theory, it is assumed that children actively create their schemas about gender by keeping or discarding information obtained through their experiences in their environment (Dinella, 2017).

Interestingly, there are two variations of gender schema theory. Bem created one theory while Martin and Halverson created another. Sandra Bem, whose notable research was published in the 1980s, conducted her research attempting to understand the development of gender roles. She believed that all of us have gender schemas which are “a cognitive structure comprising the set of attributes (behaviors, personality, appearance) that we associate with males and females” (Hyde & DeLamater, 2017, p. 33). These gender schemas are based on stereotypes and influence us to label certain behaviors as “male” or “female.” Stereotype-consistent behaviors are accepted while stereotype-inconsistent behaviors are viewed as a fluke or a rare occasion, causing us to believe the stereotypes despite many examples in our lives to disprove the stereotypes.

Overall, it is widely accepted that there are two types of schemas that are relevant in gender schema theory – superordinate schemas and own-sex schemas. Essentially, superordinate schemas guide information for gender groups whereas own-sex schemas guide information about one’s own behaviors as it relates to their own gender group (Dinella, 2017).

So why have schemas? Well, it’s a cheat sheet that makes things easier and quicker, essentially. Think about it, if you have an outline for a test that told you that the shortest answer is always the right answer, you wouldn’t even have to study. Heck, you don’t even have to ‘read’ the question options. You can simply find the choice that has the least amount of words, pick it, and you’ll ace the test (wouldn’t that be nice?!). So, gender schemas make it easier to make decisions in the moment, regarding gendered behavior. Here is an example. If a child has created a schema that says boys play with trucks, when the boy is handed a truck, he will quickly choose to play with it. However, if the truck is handed to a girl, she may quickly reject it (Dinella, 2017)

So how do children develop schemas? Well, it likely occurs in three different phases. First, children start recognizing their own gender groups and begin to build schemas. Then, a rigid phase occurs in which things are very black or white, (or, girl or boy, if you will). Things can only be one or the other, and there is very little flexibility in schemas. This occurs somewhere between ages five and seven. Lastly, a phase in which children begin to recognize that schemas are flexible and allow for a bit more of a “gray” area occurs (Dinella, 2017).

Let’s think of how schemas are used to begin to interpret one’s world. Once a child can label gender of themselves, they begin to apply schemas to themselves. So, if a schema is “Only girls cook”, then a boy may apply that to themselves and learn he cannot cook. This then guides his behavior. Martin, Eisenbud, and Rose (1995) conducted a study in which they had groups of boy toys, girl toys, and neutral toys. Children used gender schemas and gravitated to gender-normed toys. For example, boys preferred toys that an adult labeled as boy toys. If a toy was attractive (meaning a highly desired toy) but was label for girls, boys would reject the toy. They also used this reasoning to predict what other children would like. For example, if a girl did not like a block, she would indicate “Only boys like blocks” (Berk, 2004; Liben & Bigler, 2002).

Biological Theories

In regard to biological theories, there tends to be four areas of focus. Before we get into those areas, let’s remember that we are talking about gender development. That means we are not focusing on the anatomical/biological sex development of an individual, rather, we are focusing on how biological factors may impact gender development and gendered behavior. So, back to ‘there are four main areas of focus.’ The four areas of focus include (1) evolutionary theories, (2) genetic theories, (3) epigenetic theories, and (4) learning theories (don’t worry, we’ll explain how this is biology related, rather than cognitively or socially related).

Evolution Theories

Within evolution-based theories, there are three schools of thought: sex-based explanations, kinship-based explanations, and socio-cognitive explanations. Sex-based explanations explain that gendered behaviors have occurred as a way to adapt and increase the chances of reproduction. Ultimately, gender roles get divided into females focusing on rearing children and gathering food close to home, whereas males go out and hunt and protect the family. To carry out the required tasks, males needed higher androgens/testosterone to allow for higher muscle capacity as well as aggression. Similarly, females need higher levels of estrogen as well as oxytocin, which encourages socialization and bonding (Bevan, 2017). Although this may seem logical at surface level, it does not account for what we see in more egalitarian homes and cultures.

Then, there is kinship-based explanations that rationalize that very early on, we lived in groups as a means of protection and survival. As such, the groups that formed tended to be kin and shared similar DNA. Essentially, the groups with the strongest DNA that allowed for the best traits for survival, survived. Further, given that this came down to “survival of the fittest” it made sense to divvy up tasks and important behaviors. Interestingly, this was less based on sex and more on qualities of an individual, essentially using people’s strengths to the group’s advantage. This theory tends to be more supported, than sex-based theories (Bevan, 2017).

Lastly, socio-cognitive explanations explain that we have changed our environment, and that, thus, we have changed in the environment in which natural selection occurs. Essentially, when we use our cognitive abilities to create things, such as tools, we thus change our environment. We are then changing the environment that defined what behaviors/assets were necessary to survive. For example, if we can now use tools to hunt more effectively, the traditional needs of a male (as explained in sex-based theories) may be less critical in this task (Bevan, 2017).

Genetic-based Theories

We can be “genetically predisposed” to many things, mental illness, cancer, heart conditions, etc. It is theorized that we also are predisposed to gendered behavior and identification. This theory is most obvious when individuals are predisposed to a gender that does not align with biological sex, also referred to as transgender. Research has actually revealed that there is some initial evidence that gender involves somewhat of a genetic predisposition. Specifically, twin studies have shown that nonconforming gender traits, or transgender, is linked to genetic gender predispositions. More specifically, when one twin is transgender, it is more likely that the other twin is transgender as well. This phenomenon is not evidenced in fraternal twins or non-twin siblings to the same degree (Bevan, 2017).

Genetic gender predisposition theorists further reference case studies in which males with damaged genitalia undergo plastic surgery as infants to modify their genitalia to be more female aligned. These infants are then raised as girls, but often seek out transitioning back to being boys or become gender nonconforming. David Reimer is an example of one of these cases (Bevan, 2017). To learn more about this case, you can read his book, As Nature Made Him. He is given the name Joan/John in many research studies and was surgically altered by doctors to present as a female after an accident during circumcision that resulted in his castration.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/introtohumansexuality/?p=58#oembed-7

John Money, a psychologist and sexologist, was the one who encouraged David’s family to surgically alter David’s body and continued to conduct studies on the child. You can read an account of the unethical and sexual abuse that David explained he faced while participating in Money’s research. David committed suicide in 2004 after facing lifelong depression as a result of the trauma he endured.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal ideation/thoughts, there is free, confidential and 24/7 accessible assistance via 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. You can dial 988 or access information at https://988lifeline.org/. You are not alone.

Epigenetics

This area of focus does not look at DNA, but rather things that may impact DNA mutations or the expression of DNA. Really, this area falls into two subcategories: prenatal hormonal exposure and prenatal toxin exposure.

Let’s quickly recap basic biology. It is thought that gender, from a biological theory stance, begins in the fetal stage. This occurs due to varying levels of exposure to testosterone. Shortly after birth, boys experience an increase in testosterone, whereas girls experience an increase in estrogen. This difference has actually been linked to variations in social, language, and visual development between sexes. Testosterone levels have been linked to sex-typed toy play and activity levels in young children. Moreover, when females are exposed to higher levels of testosterone, they are noted to engage in more male-typical play (e.g., preference for trucks over dolls, active play over quiet), rather than female-typical play compared to their counterparts (Hines et al., 2002; Klubeck, Fuentes, Kim-Prieto, 2017; Pasterski et al., 2005). Although this has been found to be true predominantly utilizing only animal research, it is a rather simplified theory. What we have learned is that, truthfully, things are pretty complicated and other hormones and chemicals are at play (Bevan, 2017).

Prenatal toxin exposure appears to be relevant when examining diethylstilbestrol (DES), specifically. DES was prescribed to pregnant women in late 1940’s through the early 1970’s. DES was designed to mimic estrogen, and it does; however, it has many negative side effects that estrogen does not. One of the negative side-effects is that it mutates DNA and alters its expression. The reason it was finally taken off the market was because females were showing higher rates of cancer. In fact, they found that this drug had cancer-related impacts out to three generations! While there was significant research done on females, less research was done on males. However, recent studies suggest that 10% of registrants (in a national study) that were exposed to DES reported identifying as transgender or transsexual. For comparison, only 1% of the general population identifies as transgender or transsexual. Thus, it is theorized that gender development in those exposed to DES, particularly biological males, were impacted (Bevan, 2017).

Conclusion and Tips for Allyship

In reading through the ways in which gender is a social construct and varies between and within cultures, we explored BIPOC perspectives and the role of colonization in the United States from an intersectional perspective. We questioned the foundation of gender itself from an ethnorelativistic lens by looking at varying social and cultural labelings of gender around the world. While exploring psychological theories, the hope is that you have gained a better understanding of yourself and others. Gender socialization and the ways we have internalized aspects of gender shape our behavior and the way we engage with others. We may take on certain gender roles while rejecting others. Gender stereotypes and biases are present and we must analyze them to promote individual and community healing. Gender is as vast and deep as the ocean with many parts still unknown. The self is unfolding over time and it is okay to not have all the answers regarding what gender means. Moving forward, review the references and documentary below to develop skills on how to be an ally to others in order to support them along their own gender journey.