2.5: Social Change and Resistance

- Page ID

- 196201

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Sources of Social Change

Modernization and Urbanization

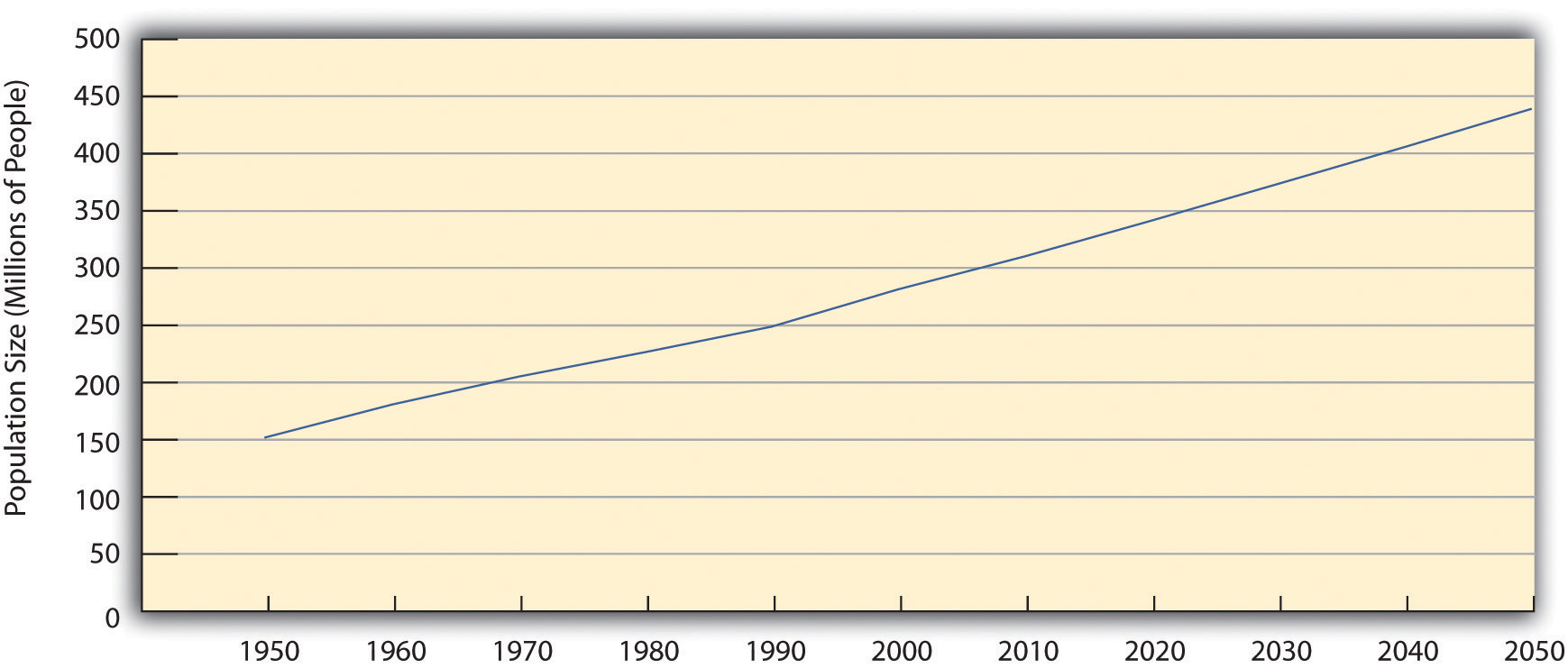

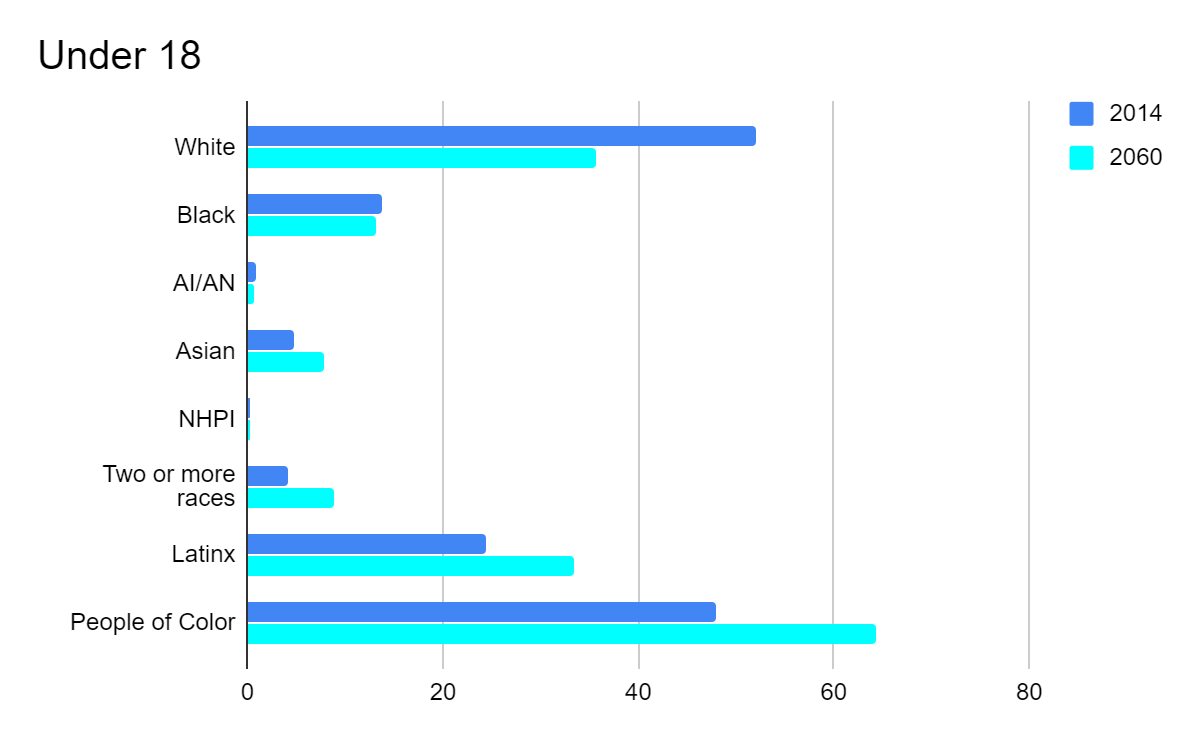

Population Growth and Composition

Culture & Technology

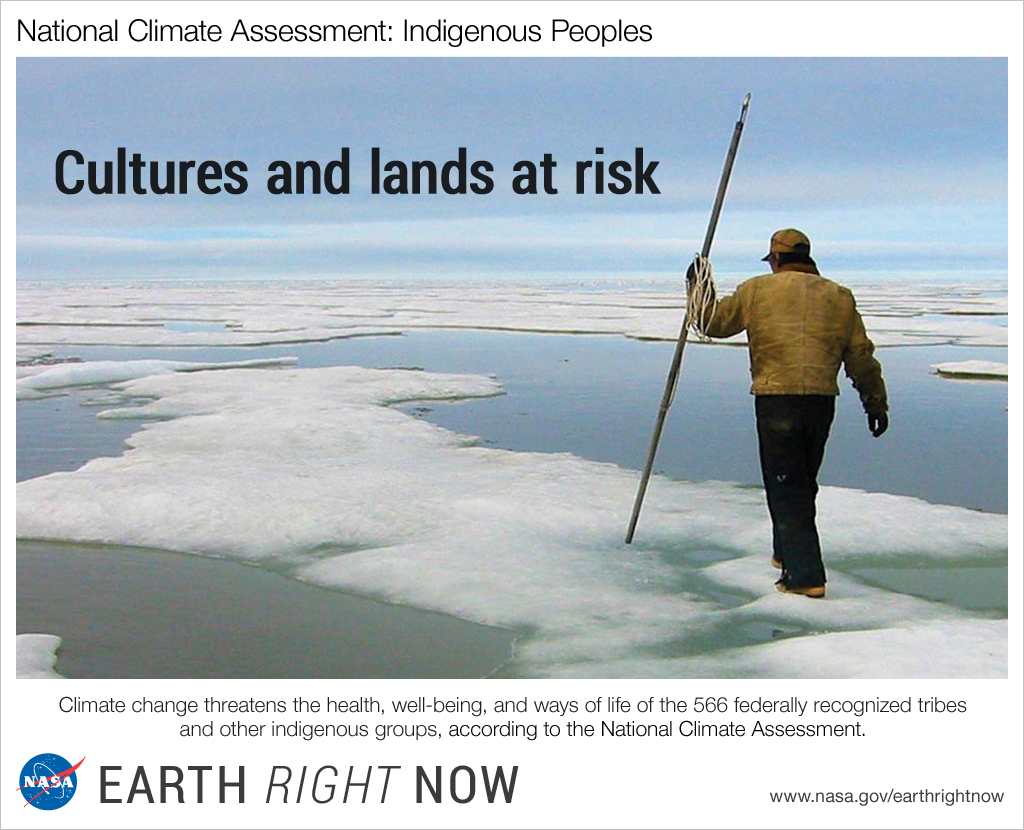

Natural Environment

Social Institutions

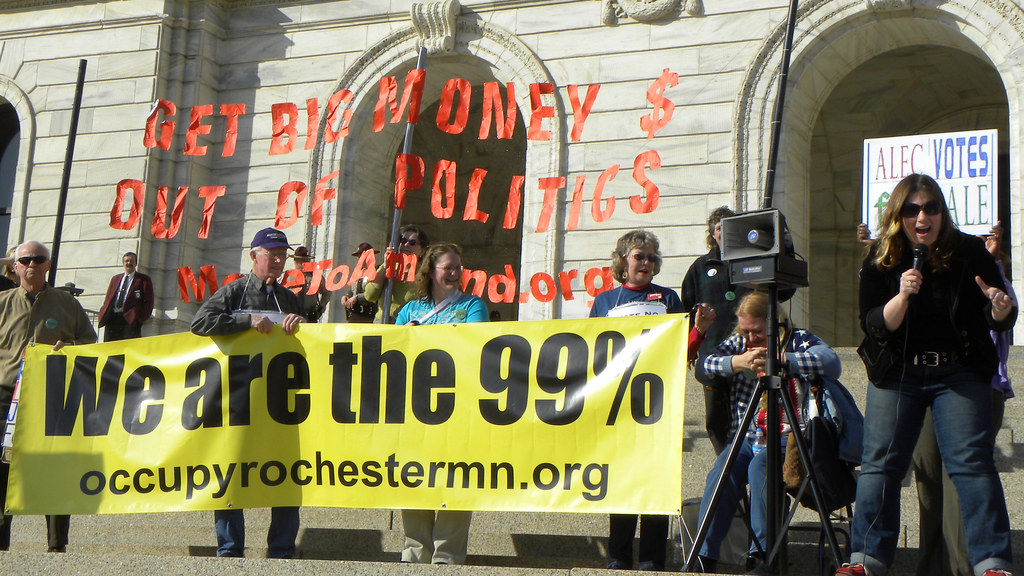

Social Movements

Types of Social Movements

We know that social movements can occur on the local, national, or even global stage. Are there other patterns or classifications that can help us understand them? Sociologist David Aberle (1966) addresses this question by developing categories that distinguish among social movements by considering what it is the movement wants to change and how much change they want. Over time, Sociologists have identified several types of social movements according to the nature and extent of the change they seek. This typology helps us understand the differences among the many kinds of social movements that existed in the past and continue to exist today (D. A. Snow & Soule, 2009).

1. Reformative

One of the most common and important types of movements is the reform movement. Reformative movements seek to change something specific about the social structure. They may seek a more limited change, but are targeted at the entire population. May be progressive or regressive. These are typically focused limited social change and focused on specific changes to individual beliefs and behavior. These include things like Alcoholics Anonymous, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), and Planned Parenthood. These are “meaning seeking,” are focused on a specific segment of the population, and their goal is to provoke radical change or spiritual growth in individuals. Some sects fit in this category.

- Progressive examples

- Historical examples include the abolitionist movement preceding the Civil War, the woman suffrage movement that followed the Civil War, the Southern civil rights movement, the gay rights movement, and the environmental movement.

2. Revolutionary/Transformative

Transformative or revolutionary movements seek to completely change every aspect of society—their goal is to change all of society in a dramatic way. They extend one large step further than a reform movement in seeking to overthrow the existing government and to bring about a new one and even a new way of life. These revolutionary or political movements seek to completely change every aspect of society.

- Examples include the Civil Rights Movement or the political movements, such as a push for communism.

3. Reactionary movements

Another type of political movement are the reactionary movements that seek to block or undo change to the social structure. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) and the Minutemen militia represent examples of reactionary movements. Both of these movements reflected white supremacy, while the KKK projected anti-Black, anti-Jewish and anti-immigrant attitudes, and the latter reflected nativism, the policy and practice of promoting the interests of "native" inhabitants against those of immigrants.

In their attempt to return the institutions and values of the past by doing away with existing ones, conservative reactionary movements seek to uphold the values and institutions of society and generally resist attempts to alter them. In contemporary society, white nationalism represents a reactionary movement which grew as a result of the "birther movement," trying to sway public opinion that President Obama was not born in the U.S. and expanded during President's Trump era with the rise of hate groups and hate crimes against Asian American Pacific Islanders, immigrants, Mexicans, and African Americans. Such conservative reactionary movements may elicit polarizing attitudes and behaviors reflecting a different type of social movement.

4. Self-Help

Two other types of movements are self -help movements and religious movements. As their name implies, self-help movements involve people trying to improve aspects of their personal lives; examples of self-help groups include Alcoholics Anonymous and Weight Watchers.

5. Religious

Religious movements aim to reinforce religious beliefs among their members and to convert other people to these beliefs. Early Christianity was certainly a momentous religious movement, and other groups that are part of a more general religious movement today include the various religious cults. Sometimes self-help and religious movements are difficult to distinguish from each other because some self -help groups emphasize religious faith as a vehicle for achieving personal transformation.

Other helpful categories that are helpful for sociologists to describe and distinguish between types of social movements include:

- Scope: A movement can be either reform or radical. A reform movement advocates changing some norms or laws while a radical movement is dedicated to changing value systems in some fundamental way. A reform movement might be a green movement advocating a sect of ecological laws, or a movement against pornography, while the American Civil Rights movement is an example of a radical movement.

- Type of Change: A movement might seek change that is either innovative or conservative. An innovative movement wants to introduce or change norms and values, like moving towards self-driving cars, while a conservative movement seeks to preserve existing norms and values, such as a group opposed to genetically modified foods.

- Targets: Group-focused movements focus on influencing groups or society in general; for example, attempting to change the political system from a monarchy to a democracy. An individual-focused movement seeks to affect individuals.

- Methods of Work: Peaceful movements utilize techniques such as nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience. Violent movements resort to violence when seeking social change. In extreme cases, violent movements may take the form of paramilitary or terrorist organizations.

- Range: Global movements, such as communism in the early 20th century, have transnational objectives. Local movements are focused on local or regional objectives such as preserving an historic building or protecting a natural habitat.

Impact of Social Movements

Resistance