6.3: How We Got Here- Lifting “The Veil”

- Page ID

- 196226

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Pre-colonial Africa

Chattel Slavery

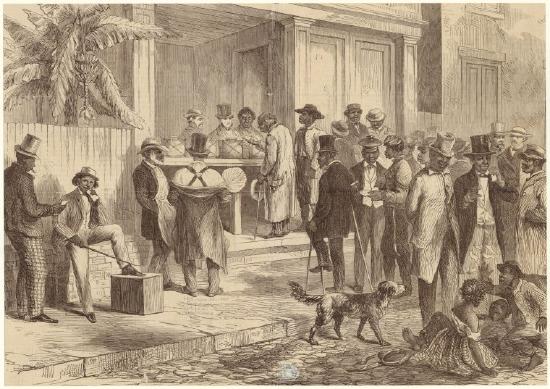

Whatever the route taken, conditions on board reflected the outsider status of those held below deck. No European, whether convict, indentured servant, or destitute free migrant, was ever subjected to the environment which greeted the typical African slave upon embarkation. The sexes were separated, kept naked, packed close together, and the men were chained for long periods. No less than 26% of those on board were classed as children, a ratio that no other pre-twentieth century migration could come close to matching. Except for the illegal period of the trade when conditions at times became even worse, slave traders typically packed two slaves per ton. While a few voyages sailing from Upper Guinea could make a passage to the Americas in three weeks, the average duration from all regions of Africa was just over two months.

Revolt and Resistance

At least two major uprisings did occur in the antebellum South. In 1811, a major rebellion broke out in the sugar parishes of the booming territory of Louisiana. Inspired by the successful overthrow of the white planter class in Haiti, Louisiana slaves took up arms against planters. Perhaps as many five hundred slaves joined the rebellion, led by Charles Deslondes, a mixed-race slave driver on a sugar plantation owned by Manuel Andry.

The revolt began in January 1811 on Andry’s plantation. Deslondes and other slaves attacked the Andry household, where they killed the slave master’s son (although Andry himself escaped). The rebels then began traveling toward New Orleans, armed with weapons gathered at Andry’s plantation. Whites mobilized to stop the rebellion, but not before Deslondes and the other rebelling slaves set fire to three plantations and killed numerous whites. A small white force led by Andry ultimately captured Deslondes, whose body was mutilated and burned following his execution. Other rebels were beheaded, and their heads placed on pikes along the Mississippi River.

The second rebellion, led by the slave Nat Turner, occurred in 1831 in Southampton County, Virginia. Turner had suffered not only from personal enslavement, but also from the additional trauma of having his wife sold away from him. Bolstered by Christianity, Turner became convinced that like Christ, he should lay down his life to end slavery. Mustering his relatives and friends, he began the rebellion August 22, killing scores of whites in the county. Whites mobilized quickly and within forty-eight hours had brought the rebellion to an end. Shocked by Nat Turner’s Rebellion, Virginia’s state legislature considered ending slavery in the state in order to provide greater security. In the end, legislators decided slavery would remain and that their state would continue to play a key role in the domestic slave trade.

Abolition Movement

Reconstruction

Sharecropping

The 13th Amendment to the constitution marked the end of slavery and led to the transition to wage labor. However, this conversion to sharecropping did not entail a new era of economic independence for former enslaved Africans but rather a continuation of internal colonialism. While they no longer faced relentless toil under the lash, freed people emerged from slavery without any money and needed farm implements, food, and other basic necessities to start their new lives. Under the sharecropping system, store owners extended credit to farmers under the agreement that the debtors would pay with a portion of their future harvest. However, the creditors charged high interest rates, making it even harder for freed people to gain economic independence.

Throughout the South, sharecropping took root, a crop-lien system that worked to the advantage of landowners. Under the system, freed people rented the land they worked, often on the same plantations where they had been slaves. Some landless whites also became sharecroppers. Sharecroppers paid their landlords with the crops they grew, often as much as half their harvest. Sharecropping favored the landlords and ensured that freed people could not attain independent livelihoods.The year-to-year leases meant no incentive existed to substantially improve the land, and high interest payments siphoned additional money away from the farmers. Sharecroppers often became trapped in a never-ending cycle of debt, unable to buy their own land and unable to stop working for their creditor because of what they owed. The consequences of sharecropping affected the entire South for many generations, severely limiting economic development and ensuring that the South remained an agricultural backwater.

| Items bought by Polly from Presley George | Amount due to Presley George from Polly |

|---|---|

| 4 3/4 Cuts of wool | $3.50 |

| 22 yds. Cloth | $11.00 |

| 5 yds. Thread | $2.50 |

| Boarding for one child | $12.00 |

| 40 bushels of corn | $40.00 |

| Total Payment | $69.00 |

| Amount of work and by whom | Presley George's payment for Polly and her family's work |

|---|---|

| 3 months of work by Polly | $12.00 |

| 4 months of work by Peter (son) | $32.00 |

| 4 months of work by Burrell (son | $16.00 |

| 4 months of work by Siller (daughter) | $9.00 |

| Total Payment | $69.00 |

The excerpt below, extracted from The Life Stories of Undistinguished Americans as Told by Themselves further conveys the blurred line of distinction between slavery and sharecropping, "freedom," further conveying the parallel exploitation in either system:

Slabery an' freedom (Slavery and freedom)

Dey's mos' de same (They're mostly the same)

No difference hahdly (No difference hardly)

Cep' in de name. (Except in the name).

The Era of Jim Crow

Because of Jim Crow laws and a wish to support their community, residents spent their money within Greenwood, feeding the growth of the economy. A wide variety of professionals, entrepreneurs, and workers shared quality school and hospital systems, a public library, hotels, parks, and theaters in Greenwood. During this time, African Americans struggled to gain access to these features of city life because of segregation. The homes in the densely populated district ranged from thrown-together shanties to luxurious multi-story homes on “Professor’s Row.” Greenwood attracted nationally renowned African American leaders and activists such as Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. DuBois. In fact, Booker T. Washington gave Greenwood its nickname: Black Wall Street due to its economic, political, and social significance.

However, in 1921, the District was massacred by a white mob for two days in one of the largest acts of racialized terrorist violence in U.S. history. Hundreds of people died or went missing, and nearly a thousand were injured. This attack was devastating not just for the victims, but it also became an enduring symbol of the threat of white violence in the face of Black prosperity, fueling the flames of white supremacy.

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) : Tulsa Race Massacre, 1921. (CC PDM 1.0; 1619126 Oklahoma Historical Society Photograph Collection (OHS) via OKHistory)

Disenfranchisement

In the South, electoral politics remained a parade of electoral fraud, voter intimidation, and race-baiting. The question was how to accomplish disfranchisement. The 15th Amendment clearly prohibited states from denying any citizen the right to vote on the basis of race. In 1890 the state of Mississippi took on this legal challenge. A state newspaper called on politicians to devise “some legal defensible substitute for the abhorrent and evil methods on which white supremacy lies.” The state’s Democratic Party responded with a new state constitution designed to purge corruption at the ballot box through disenfranchisement. Those hoping to vote in Mississippi would have to jump through a series of hurdles designed with the explicit purpose of excluding the state’s African American population from political power.

The state first established a poll tax, which required voters to pay for the privilege of voting. Second, it stripped the suffrage from those convicted of petty crimes most common among the state’s African Americans. Next, the state required voters to pass a literacy test. Local voting election officials, who were themselves part of the local party machine, were responsible for judging whether voters were able to read and understand a section of the Constitution. In order to protect illiterate whites from exclusion, the so called “understanding clause” allowed a voter to qualify if they could adequately explain the meaning of a section that was read to them. In practice these rules were systematically abused to the point where local election officials effectively wielded the power to permit and deny suffrage at will.

The disenfranchisement laws effectively moved electoral conflict from the ballot box, where public attention was greatest, to the voting registrar, where supposedly color-blind laws allowed local party officials to deny the ballot without the appearance of fraud.

Between 1895 and 1908 the rest of the states in the South approved new constitutions including these disenfranchisement tools. Six southern states also added a grandfather clause, which bestowed the suffrage on anyone whose grandfather was eligible to vote in 1867. This ensured that whites who would have been otherwise excluded would still be eligible, at least until it was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1915. Finally, each southern state adopted an all-white primary, excluded Blacks from the Democratic primary, the only political contests that mattered across much of the South.

Segregation

At the same time that the South’s Democratic leaders were adopting the tools to disenfranchise the region’s Black voters, these same legislatures were constructing a system of racial segregation even more pernicious. While it built on earlier practice, segregation was primarily a modern and urban system of enforcing racial subordination and deference. In rural areas, white and Black southerners negotiated the meaning of racial difference within the context of personal relationships of kinship and patronage. An African American who broke the local community’s racial norms could expect swift personal sanctions that often included violence. The crop lien and convict lease systems were the most important legal tools of racial control in the rural South. Maintaining white supremacy there did not require segregation. Maintaining white supremacy within the city, however, was a different matter altogether. As the region’s railroad networks and cities expanded, so too did the anonymity and therefore freedom of southern Blacks. Southern cities were becoming a center of Black middle class life that was an implicit threat to racial hierarchies. White southerners created the system of segregation as a way to maintain white supremacy in restaurants, theaters, public restrooms, schools, water fountains, train cars, and hospitals. Segregation inscribed the superiority of whites and the deference of Blacks into the very geography of public spaces.

As with disenfranchisement, segregation violated a plain reading of the constitution—in this case the Fourteenth Amendment. Here the Supreme Court intervened, ruling in the Civil Rights Cases (1883) that the Fourteenth Amendment only prevented discrimination directly by states. It did not prevent discrimination by individuals, businesses, or other entities. Southern states exploited this interpretation with the first legal segregation of railroad cars in 1888. In a case that reached the Supreme Court in 1896, New Orleans resident Homer Plessy challenged the constitutionality of Louisiana’s segregation of streetcars. The court ruled against Plessy and, in the process, established the legal principle of separate but equal. Racially segregated facilities were legal provided they were equivalent. In practice this was rarely the case. The court’s majority defended its position with logic that reflected the racial assumptions of the day. “If one race be inferior to the other socially,” the court explained, “the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.” Justice John Harlan, the lone dissenter, countered, “our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law” Harlan went on to warn that the court’s decision would “permit the seeds of race hatred to be planted under the sanction of law.” In their rush to fulfill Harlan’s prophecy, southern whites codified and enforced the segregation of public spaces.

Segregation was built on a fiction—that there could be a white South socially and culturally distinct from African Americans. Its legal basis rested on the constitutional fallacy of “separate but equal” as declared by Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). Southern whites erected a bulwark of white supremacy that would last for nearly sixty years. Segregation and disenfranchisement in the South rejected Black citizenship and relegated Black social and cultural life to segregated spaces. African Americans lived divided lives, acting the part whites demanded of them in public, while maintaining their own world apart from whites. This segregated world provided a measure of independence for the region’s growing Black middle class, yet at the cost of poisoning the relationship between Black and white. Segregation and disenfranchisement created entrenched structures of racism that completed the total rejection of the promises of Reconstruction.

Video 6.3.1 : "Plessy v. Ferguson Summary - Quimbee.com." (Close-captioning and other YouTube settings will appear once the video starts.) (Fair Use; Quimbee via YouTube)

School Segregation

Older battles over racial exclusion also confronted postwar American society. One long-simmering struggle targeted segregated schooling. Since the Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), Black Americans, particularly in the American South, had fully felt the deleterious effects of segregated education. Their battle against Plessy for inclusion in American education stretched across half a century when the Supreme Court again took up the merits of “separate but equal.”

On May 17, 1954, after two years of argument, re-argument, and deliberation, Chief Justice Earl Warren announced the Supreme Court’s decision on segregated schooling in Oliver Brown, et al v. Board of Education of Topeka, et al. The court found by a unanimous 9-0 vote that racial segregation violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The court’s decision declared, “Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” “Separate but equal” was made unconstitutional.

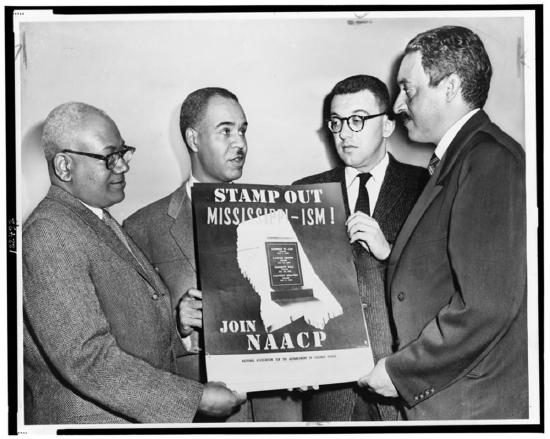

Decades of African American-led litigation, local agitation against racial inequality, and liberal Supreme Court justices made Brown v. Board possible. In the early 1930s, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) began a concerted effort to erode the legal underpinnings of segregation in the American South. De jure segregation (legal segregation) subjected racial minorities to discriminatory laws and policies. Law and custom in the South hardened anti-Black restrictions. But through a series of carefully chosen and contested court cases concerning education, disfranchisement, and jury selection, NAACP lawyers such as Charles Hamilton Houston, Robert L. Clark, and future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall undermined Jim Crow’s constitutional underpinnings. Initially seeking to demonstrate that states systematically failed to provide African American students “equal” resources and facilities, and thus failed to live up to Plessy, by the late 1940s activists began to more forcefully challenge the assumptions that “separate” was constitutional at all.

Though remembered as just one lawsuit, Brown consolidated five separate cases that had originated in the southeastern United States: Briggs v. Elliott (South Carolina), Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (Virginia), Beulah v. Belton (Delaware), Boiling v. Sharpe(Washington, D. C.), and Brown v. Board of Education (Kansas). Working with local activists already involved in desegregation fights, the NAACP purposely chose cases with a diverse set of local backgrounds to show that segregation was not just an issue in the Deep South, and that a sweeping judgment on the fundamental constitutionality of Plessy was needed.

Briggs v. Elliott had illustrated, on the one hand, the extreme deficiencies in segregated Black schools. The first case accepted by the NAACP, Briggs originated in rural Clarendon County, South Carolina, where taxpayers in 1950 spent $179 to educate each white student while spending $43 for each Black student. The district’s twelve white schools were cumulatively worth $637,850; the value of its sixty-one Black schools (mostly dilapidated, over-crowded shacks), was $194,575. While Briggs underscored the South’s failure to follow Plessy, the Brown v. Board suit focused less on material disparities between Black and white schools (which were significantly less than in places like Clarendon County) and more on the social and spiritual degradation that accompanied legal segregation. This case cut to the basic question of whether or not “separate” was itself inherently unequal. The NAACP said the two notions were incompatible. As one witness before the U. S. District Court of Kansas said, “the entire colored race is craving light, and the only way to reach the light is to start [Black and white] children together in their infancy and they come up together.”

To make its case, the NAACP marshaled historical and social scientific evidence. The Court found the historical evidence inconclusive and drew their ruling more heavily from the NAACP’s argument that segregation psychologically damaged Black children. To make this argument, association lawyers relied upon social scientific evidence, such as the famous doll experiments of Kenneth and Mamie Clark. The Clarks demonstrated that while young white girls would naturally choose to play with white dolls, young Black girls would, too. The Clarks argued that Black children’s aesthetic and moral preference for white dolls demonstrated the pernicious effects and self-loathing produced by segregation. The doll experiments illustrated one psychological effect of segregation on communities of color - internalized racism, an acceptance of the racial hierarchy that places whites consistently above people of color.

Identifying and denouncing injustice, though, is different from rectifying it. Though Brown repudiated Plessy, the Court’s orders did not extend to segregation in places other than public schools and, even then, while recognizing the historical importance of the decision, the justices set aside the divisive yet essential question of remediation and enforcement to preserve a unanimous decision. Their infamously ambiguous order in 1955 (what came to be known as Brown II) that school districts desegregate “with all deliberate speed” was so vague and ineffectual that it left the actual business of desegregation in the hands of those who opposed it.

In most of the South, as well as the rest of the country, school integration did not occur on a wide scale until well after Brown. Only in the 1964 Civil Rights Act did the federal government finally implement some enforcement of the Brown decision by threatening to withhold funding from recalcitrant school districts, financially compelling desegregation, but even then southern districts found loopholes. Court decisions such as Green v. New Kent County (1968) and Alexander v. Holmes (1969) finally closed some of those loopholes, such as “freedom of choice” plans, to compel some measure of actual integration.

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): African American students who desegregated white schools, the “Little Rock Nine” (Arkansas), were escorted by, the 101st Airborne Division of the U.S. Army. (CC BY 2.0; U.S. Army via Wikimedia/Flickr)

When Brown finally was enforced in the South, the quantitative impact was staggering. In the early 1950s, virtually no southern Black students attended white schools. By 1968, fourteen years after Brown, some eighty percent of Black southerners remained in schools that were ninety- to one-hundred-percent nonwhite. By 1972, though, just twenty-five percent were in such schools, and fifty-five percent remained in schools with a simple nonwhite minority. By many measures, the public schools of the South ironically became the most integrated in the nation.

As a landmark moment in American history, Brown’s significance perhaps lies less in what immediate tangible changes it wrought in African American life—which were slow, partial, and inseparable from a much longer chain of events—than in the idealism it expressed and the momentum it created. The nation’s highest court had attacked one of the fundamental supports of Jim Crow segregation and offered constitutional cover for the creation of one of the greatest social movements in American history.

Contributors and Attributions

- Johnson, Shaheen. (Long Beach City College)

- Hund, Janét. (Long Beach City College)

- An Overview of the Trans-Atlantic (Dr. David Eltis) (CC BY-NC 3.0 US)

- United States History 1 (Lumen) (CC BY 4.0)

- Jim Crow Laws/Segregation Introduction (OER Commons) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

- The Tulsa Race Massacre (Oklahoma Historical Society/OER Commons) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

- Content taken from 7.2: Intergroup Relations is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, & Joy Tsuhako (ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)) .

References

Holt, Hamilton. (1906). The Life Stories of Undistinguished Americans as Told by Themselves. Routledge.

Lott, E. (1993). Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. Oxford University Press.

Macat. (2015). An Introduction to W.E.B. Du Bois' The Souls of Black Folk-Macat Sociology Analysis. [Video].

Merenda, C. (2015). Kenneth and Mamie Clark: A Biographic Video. [Video]. YouTube.

Niagara Movement. (n.d.). Encyclopedia Britannica.

Quimbee. (2017). Plessy v. Ferguson Summary. [Video]. YouTube.

Takaki, R. (2008). A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America. Back Bay Books.

Woodward, V.C. (1955). The Strange Career of Jim Crow. Oxford University Press.