7.5: Roots and Resistance- The Development of Chicanx and Latinx Studies

- Page ID

- 196239

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Establishing Chicanx and Latinx Studies in Higher Education

Little School of the 400

The East L.A. Blowouts

The Original 26 Demands of the East L.A. Walkouts

El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán

M.E.Ch.A. and El Plan de Santa Bárbara

Latinx Social Movements: Historical Timeline

This timeline section comes from 8.5: Social Change and Resistance is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, & Joy Tsuhako (ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)) .

1900s

1903 In Oxnard, Calif., more than 1,200 Mexican and Japanese farm workers organize the first farm worker union, the Japanese-Mexican Labor Association (JMLA). Later, it will be the first union to win a strike against the California agricultural industry, which already has become a powerful force.

1904 The U.S. establishes the first border patrol as a way to keep Asian laborers from entering the country by way of Mexico.

1905 Labor organizer Lucy Gonzales Parsons, from San Antonio, Texas, helps found the Wobblies, the Industrial Workers of the World.

1910s

1910 The Mexican Revolution forces Mexicans to cross the border into the United States, in search of safety and employment.

1911 The first large convention of Mexicans to organize against social injustice, El Primer Congreso Mexicanista, meets in Laredo, Texas.

1912 New Mexico enters the union as an officially bilingual state, authorizing funds for voting in both Spanish and English, as well as for bilingual education. Article XII of the state constitution also prohibits segregation for children of "Spanish descent." At the state's constitutional convention six years earlier, Mexican American delegates mandated Spanish and English be used for all state business.

1914 The Colorado militia attacks striking coal miners in what becomes known as the Ludlow Massacre. More than 50 people are killed, mostly Mexican Americans, including 11 children and three women.

1917 Factories in war-related industries need more workers, as Americans leave for war. Latinos from the Southwest begin moving north in large numbers for the first time. They find ready employment as machinists, mechanics, furniture finishers, upholsterers, printing press workers, meat packers and steel mill workers.

1917 The U.S. Congress passes the Jones Act, granting citizenship to Puerto Ricans under U.S. military rule since the end of the Spanish-American War.

1920s

1921 San Antonio's Orden Hijos de América (Order of the Sons of America) organizes Latino workers to raise awareness of civil rights issues and fight for fair wages, education and housing.

1921 The Immigration Act of 1921 restricts the entry of southern and eastern Europeans. Agricultural businesses successfully oppose efforts to limit the immigration of Mexicans.

1927 In Los Angeles, the Confederación de Uniones Obreras Mexicanas (Federation of Mexican Workers Union-CUOM) becomes the first large-scale effort to organize and consolidate Mexican workers.

1928 Octaviano Larrazolo of New Mexico becomes the first Latino U.S. Senator.

1929 Several Latino service organizations merge to form the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). The group organizes against discrimination and segregation and promotes education among Latinos. It's the largest and longest-lasting Latino civil rights group in the country.

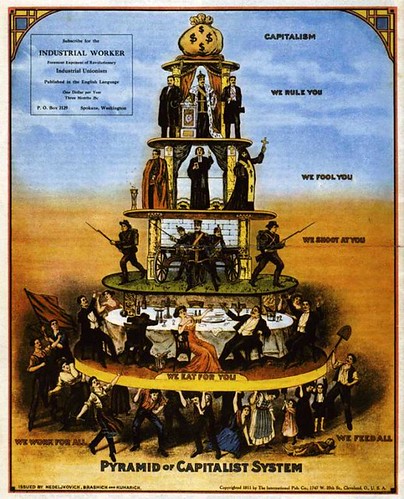

(Public Domain)

1930s

1931 The country's first labor strike incited by a cultural conflict happens in Ybor City (Tampa), Fla., when the owners of cigar factories attempt to get rid of the lectores, people who read aloud from books and magazines as a way to help cigar rollers pass the time. The owners accuse the lectores of radicalizing the workers and replace them with radios. The workers walk out.

1932 Benjamin Nathan Cardozo, a Sephardic Jew, becomes the first Latino named to the U.S. Supreme Court.

1933 Latino unions in California lead the El Monte Strike, possibly the largest agricultural strike at that point in history, to protest the declining wage rate for strawberry pickers. By May 1933, wages dropped to nine cents an hour. In July, growers agreed to a settlement including a wage increase to 20 cents an hour, or $1.50 for a nine-hour day of work.

1938 On December 4, El Congreso del Pueblo de Habla Española (The Spanish-Speaking Peoples Congress) holds its first conference in Los Angeles. Founded by Luisa Moreno and led by Josefina Fierro de Bright, it's the first national effort to bring together Latino workers from different ethnic backgrounds: Cubans and Spaniards from Florida, Puerto Ricans from New York, Mexicans and Mexican Americans from the Southwest.

1939 Novelist John Steinbeck publishes The Grapes of Wrath, calling attention to the plight of migrant workers in the California grape-growing industry.

1940s

1941 The U.S. government forms the Fair Employment Practices Committee to handle cases of employment discrimination. Latino workers file more than one-third of all complaints from the Southwest.

1942 The Bracero Program begins, allowing Mexican citizens to work temporarily in the United States. U.S. growers support the program as a source or low-cost labor. The program welcomes millions of Mexican workers into the U.S. until it ends in 1964.

1942 Hundreds of thousands of Latinos serve in the armed forces during World War II.

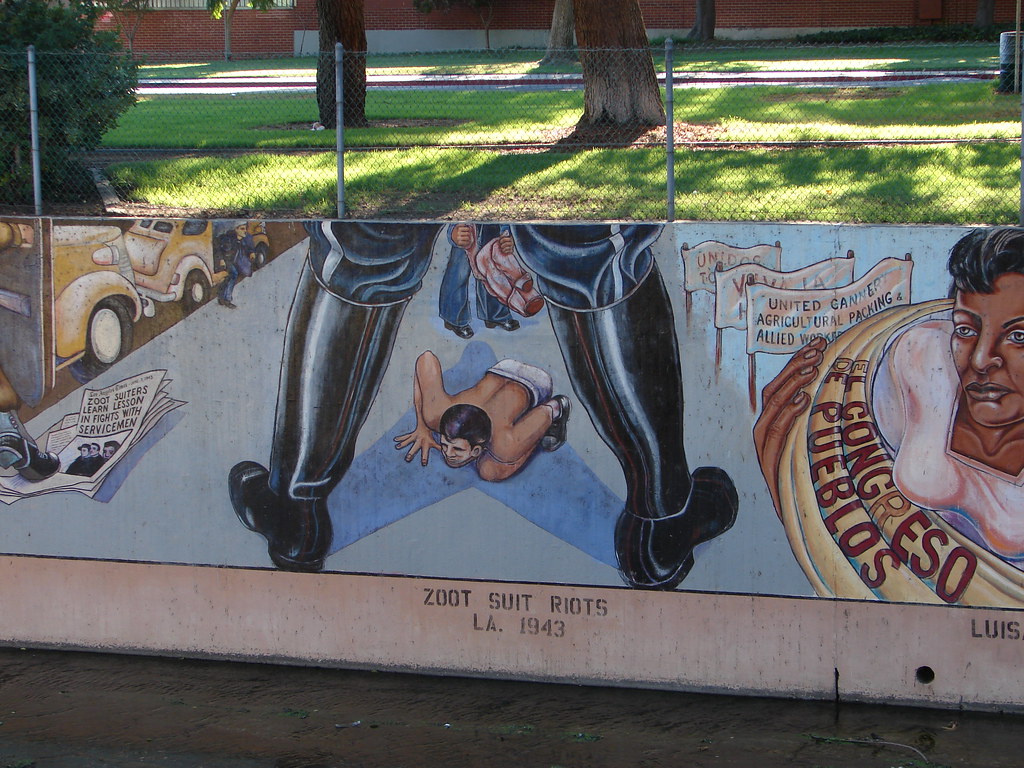

1943 Los Angeles erupts in the Zoot Suit Riots, the worst race riots in the city to date. For 10 nights, American sailors cruise Mexican American neighborhoods in search of "zoot-suiters" -- hip, young Mexican teens dressed in baggy pants and long-tailed coats. The military men drag kids -- some as young as 12 years old -- out of movie theaters and cafes, tearing their clothes off and viciously beating them.

1944 Senator Dennis Chávez of New Mexico introduces the first Fair Employment Practices Bill, which prohibits discrimination because of race, creed or national origin. The bill fails, but is an important predecessor for the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

1945 Latino veterans return home with a new feeling of unity. Together, they seek equal rights in the country they defended. They use their G.I. benefits for personal advancement, college educations and buying homes. In 1948, they will organize the American G.I. Forum in Texas to combat discrimination and improve the status of Latinos; branches eventually form in 23 states.

1945 Mexican-American parents sue several California school districts, challenging the segregation of Latino students in separate schools. The California Supreme Court rules in the parents' favor in Mendez v. Westminster, arguing segregation violates children's constitutional rights. The case is an important precedent for Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

1950s

1953 During "Operation Wetback" from 1953 and 1958, the U.S. Immigration Service arrests and deports more than 3.8 million Latin Americans. Many U.S. citizens are deported unfairly, including political activist Luisa Moreno and other community leaders.

1954 Hernandez v. Texas is the first post-WWII Latino civil rights case heard and decided by the U.S. Supreme Court. The Hernandez decision strikes down discrimination based on class and ethnic distinctions.

1960s

1962 Air flights between the U.S. and Cuba are suspended following the Cuban Missile Crisis. Prior to the Crisis, more than 200,000 of Cuba's wealthiest and most affluent professionals fled the country fearing reprisals from Fidel Castro's communist regime. Many believed Castro would be overthrown and they would soon be able to return to Cuba.

1963 Miami's Coral Way Elementary School offers the nation's first bilingual education program in public schools, thanks to a grant from the Ford Foundation.

1965 Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta found the United Farm Workers association, in Delano, Calif., which becomes the largest and most important farm worker union in the nation. Huerta becomes the first woman to lead such a union. Under their leadership, the UFW joins a strike started by Filipino grape pickers in Delano. The Grape Boycott becomes one of the most significant social justice movements for farm workers in the United States.

1965 Luis Valdez founds the world-famous El Teatro Campesino, the first farm worker theatre, in Delano, Calif. Actors entertain and educate farm workers about their rights.

1966 Congress passes the Cuban American Adjustment Act allowing Cubans who lived in America for at least one year to become permanent residents. No other immigrant group has been offered this privilege before, or since.

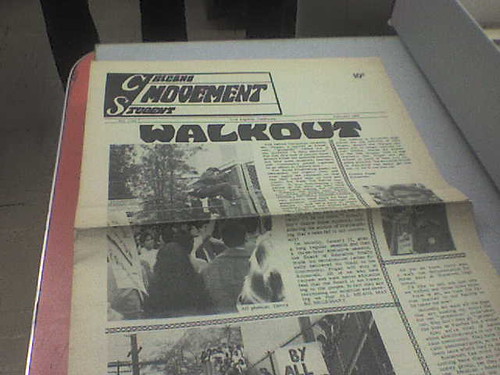

1968 Latino high school students in Los Angeles stage citywide walkouts protesting unequal treatment by the school district. Prior to the walkouts, Latino students were routinely punished for speaking Spanish on school property, not allowed to use the bathroom during lunch, and actively discouraged from going to college. Walkout participants are subjected to police brutality and public ridicule; 13 are arrested on charges of disorderly conduct and conspiracy. However, the walkouts eventually result in school reform and an increased college enrollment among Latino youth.

1968 The Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund opens its doors, becoming the first legal fund to pursue protection of the civil rights of Mexican Americans.

1969 Faced with slum housing, inadequate schools and rising unemployment, Puerto Rican youth in Chicago form the Young Lords Organization, inspired in part by the writings of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. An outgrowth of the Young Lords street gang, the YLO becomes a vibrant community organization, creating free breakfast programs for kids and community health clinics. Modeled after the Black Panthers, the YLO uses direct action and political education to bring public attention to issues affecting their community. The group later spreads to New York City.

1970s

Throughout the 1970s, progressive organizations based in Mexican, Filipino, Arab and other immigrant communities begin organizing documented and undocumented workers. Together, they work for legalization and union rights against INS raids and immigration law enforcement brutality.

1970 The U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare issues a memorandum saying students cannot be denied access to educational programs because of an inability to speak English.

1974 In the case Lau v. Nichols, the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirms the 1970 memorandum, ruling students' access to, or participation in, an educational program cannot be denied because of their inability to speak or understand English. The lawsuit began as a class action by Chinese-speaking students against the school district in San Francisco, although the decision benefited other immigrant groups, as well.

1974 Congress passes the Equal Educational Opportunity Act of 1974 to make bilingual education more widely available in public schools.

1974 The first major Latino voter registration organization, the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project begins, registering more than two million Latino voters in the first 20 years.

1975 After non-English speakers testify about the discrimination they face at the polls, Congress votes to expand the U.S. Voting Rights Act to require language assistance at polling stations. Native Americans, Asian Americans, Alaska Natives and Latinos benefit most from this provision. The original Act, passed in 1965, applied only to Blacks and Puerto Ricans. The Voting Rights Act leads to the increasing political representation of Latinos in U.S. politics.

1980s

1985 National religious organizations provide support for the first "National Consultation on Immigrant Rights." Immediately the group calls for a National Day of Action for Justice for Immigrants and Refugees, "to call attention to issues and to dramatize the positive role of immigrants in shaping U.S. society." More than 20 cities participate in the event.

1986 On November 6, Congress approves the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), providing legalization for certain undocumented workers, including agricultural workers. The Act also sets employer sanctions in place, making it illegal for employers to hire undocumented workers.

1988 President Ronald Reagan appoints Dr. Lauro Cavazos as Secretary of Education. He becomes the first Latino appointed to a presidential cabinet.

1989 Miami's Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, a Cuban American, becomes the first Latino woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

1990s

1990 The California Delegation Against Hate Violence documents the increasing human rights abuses by INS agents and private citizens against migrants in the San Diego-Tijuana border area.

1992 The Los Angeles Police Department cracks down on Latino immigrants during the "Los Angeles rebellion," after the "not guilty" verdict in the Rodney King police brutality case.

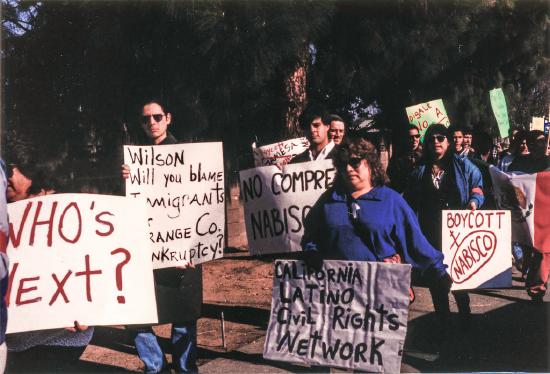

1994-1995 The fight over California's Proposition 187 brings the debate over immigration --particularly undocumented immigration -- to the front pages of the national press. The ballot initiative galvanizes students across the state, who mount a widespread campaign in opposition. Voters approve the measure preventing undocumented immigrants from obtaining public services like education and health care.

1997 A U.S. District Court judge overturns California's Prop 187, ruling it unconstitutional.

1999 After sixty years of U.S. Navy exercise-bombings on the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, civil rights leaders in both Puerto Rican and African American communities respond with a non-violent protest galvanizing the island's 9,300 residents. Triggered by the accidental death of a Puerto Rican naval base employee during live ammunition exercises, Puerto Ricans unite in outrage, protesting the proximity of the exercises to civilians, years of environmental destruction and resulting health problems. The Navy failed to honor historical agreements to treat the island and its people respectfully. The protests culminate in lawsuits and the arrest of more than 180 protesters, with some serving unnecessarily harsh sentences. The Navy promises to stop bombing the island by 2003.

1999 The Immigration Law Enforcement Monitoring Project coordinates nationwide activities on Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead. Public displays of crosses, representing those who died crossing the border, capture public and media attention.

2000s

2001 Following the terrorist attacks of 9/11, Arab Americans and others of Middle Eastern descent experience a backlash in the United States, as hate crimes, harassment and police profiling sharply increase. Based in rising fears over "border security," the stigma spreads to other immigrant groups. Some politicians call for building a wall between the United States and Mexico. During the next five years, Latino immigrants face a surge in discrimination and bias.

2003 Latinos are pronounced the nation's largest people of color --- surpassing African Americans --- after new Census figures show the U.S. Latino population at 37.1 million. The number is expected to triple by the year 2050.

2004 The Minuteman Project begins to organize anti-immigrant activists at the U.S./Mexico border. The group considers itself a citizen's border patrol, but several known white supremacists are members. During the next two years, the Minuteman Project gains widespread press coverage. Immigrant rights supporters conduct counter-rallies in public opposition to the Minuteman Project's tactics and beliefs.

2005 Just as key provisions of the Voting Rights Act are about to expire, English-only conservatives oppose its renewal because of the expense of bilingual ballots. In August 2006, President George W. Bush will reauthorize the Act. The reauthorized Act will be named the "Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, Coretta Scott King, and Cesar Chavez Voting Rights Act Reauthorization and Amendments Act of 2006."

2006 Immigrants -- mostly Latinos -- and their allies launch massive demonstrations in cities and towns across the country in support of immigrant rights and to protest the growing resentment toward undocumented workers.

2006 High school students, mostly but not exclusively Latino, stage walkouts in Los Angeles, Houston and other cities, boycotting schools and businesses in support of immigrant rights and equality. Schools issue suspensions and truancy reports to students who participate, and several students are arrested.

2006 On May 1, hundreds of thousands of Latino immigrants and others participate in the Day Without Immigrants, boycotting work, school and shopping, to symbolize the important contributions immigrants make to the American economy.

2006 The U.S. Congress debates legislation that would criminalize undocumented immigrants. Immigrant rights organizations support alternative legislation offering a pathway to citizenship. The legislation stalls, and Congress decides instead to hold hearings across the country during the summer and fall of 2006, to gain public input on how to handle the immigration issue.

2010s

2012 After sustained protest and direct action, immigrant rights activists and supporters pressure Obama to pass DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals). This executive order provides protection for undocumented young people who were brought to the United States as children. They were also able to apply for a driver's license, work permit, and relief from deportation proceedings.

Contributors and Attributions

- Ramos, Carlos. (Long Beach City College)

- Tsuhako, Joy. (Cerritos College)

- 8.5: Social Change and Resistance is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, & Joy Tsuhako (ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)) .

- Colby S. & Ortman J. (2015). Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 - 2060. U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Reports. March 2015

- Da Costa, K. (2005). Redrawing the color line? The problems and possibilities of multiracial families and group making. In Gallagher C. (Ed.) Rethinking the Color Line (2018) 6th Edition. Sage.

- Gómez, L. E. (2020). Inventing Latinos: A New Story of American Racism. New Press.

- Haney-López, I. (2003). Racism on Trial: The Chicano Fight for Justice. Harvard University Press.

- Livingston, G. & Brown, A. (2017). Intermarriage in the U.S. 50 years after Loving v. Virginia. Pew Research Center.

- Mariscal, G. (2005). Brown-eyed Children of the Sun: Lessons from the Chicano Movement, 1965-1975. University of New Mexico Press.

- NCYLC. (2006, February 12). El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán. Retrieved December 12, 2022, from http://clubs.arizona.edu/~mecha/page...anDeAtzlan.pdf

- Olmos, E. J. (Director). (2006). Walkout [Film]. HBO.

- Ortiz, V., & Telles, E. (2012). Racial identity and racial treatment of Mexican Americans. Race and Social Problems, 4(1).

- Quintanilla, G. (1976). The "Little School of 400". https://eric.ed.gov. Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://eric.ed.gov/?q=the+little+sc...00&id=ED158905

- Rosales, F. A. (1997). Chicano! The History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement. Arte Público Press.

- Samora, Julian. (1993). A History of the Mexican-American People. University of Notre Dame Press.

- Sleeter, C. E., Cuauhtin, R. T., Zavala, M., & Au, W. (Eds.). (2019). Rethinking Ethnic Studies. Rethinking Schools.

- Southern Poverty Law Center. (2020). Teaching Tolerance. Southern Poverty Law Center.

- Terriquez, V. (2015 August). Intersectional mobilization, social movement spillover, and queer youth leadership in the immigrant rights movement. Social Problems, 62(3), 343–362.

- Thompson, H. S. (1998). Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

- Tijerina, F. (1962). What Price Education? National Institute of Education, 18. ERIC. Retrieved 12 12, 2022, from https://eric.ed.gov/?q=the+little+sc...on&id=ED124311