8.7: Intersectionality

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 196256

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Women and Gender Issues

Where Do Women Fit In?

Asian America has masked a series of internal tensions. In order to produce a sense of racial solidarity, Asian American activists framed social injustices in terms of race, veiling other competing social categories such as gender, sexuality, ethnicity, and nationality. The relative absence of gender as a lens for Asian American activism and resistance throughout the 1970s until the present should therefore be read as neither an indication of the absence of gender inequality nor of the disengagement of Asian American women from issues of social justice.

Many Asian American activists (including some of the authors in this book) refute the label "feminist" although their work pays special attention to the experiences of women. Sometimes this feeling reflects a fear of alienating men -- a consequence that seems inevitable if men are unable to own up to their gender privilege. At other times, the antipathy towards feminism reflects the cultural insensitivity and racism of white, European feminists.

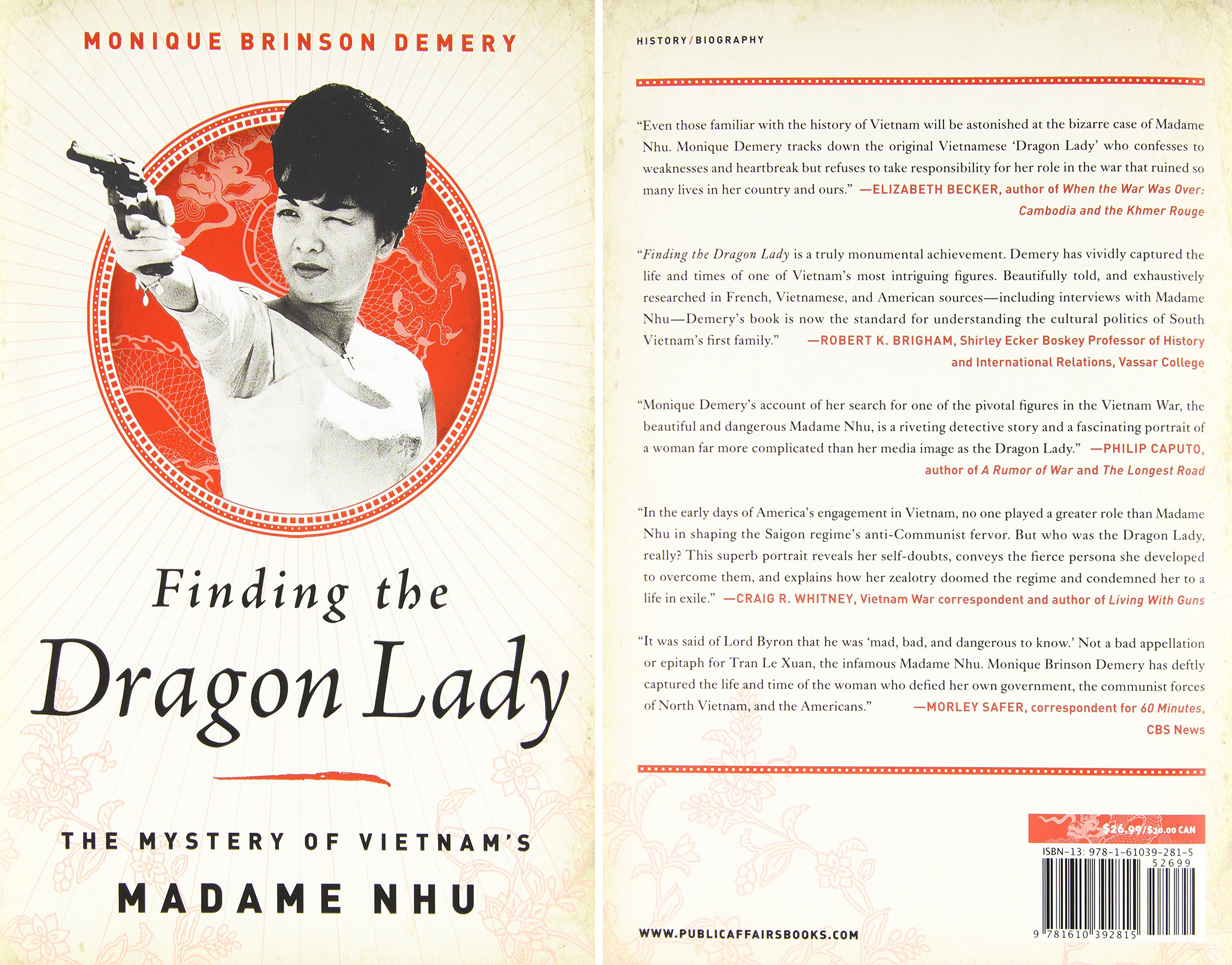

Dragon Ladies: A Brief History

Empress Tsu-his ruled China from 1898 to 1908 from the Dragon Throne. The New York Times described her as "the wicked witch of the East, a reptilian dragon lady who had arranged the poisoning, strangling, beheading, or forced suicide of anyone who had ever challenged her autocratic rule." The shadow of the Dragon Lady -- with her cruel, perverse, and inhuman ways -- continued to darken encounters between Asian women and the West they flocked to for refuge.

Far from being predatory, many of the first Asian women to come to the U.S. in the mid-1800s were disadvantaged Chinese women, who were tricked, kidnapped, or smuggled into the country to serve the predominantly male Chinese community as prostitutes. The impression that all Asian women were prostitutes, born at that time, "colored the public perception of, attitude toward, and action against all Chinese women for almost a century," writes historian Sucheng Chan.

Police and legislators singled out Chinese women for special restrictions "not so much because they were prostitutes as such (since there were also many white prostitutes around) but because -- as Chinese -- they allegedly brought in especially virulent strains of venereal diseases, introduced opium addiction, and enticed white boys into a life of sin," Chan also writes. Chinese women who were not prostitutes ended up bearing the brunt of the Chinese exclusion laws that passed in the late 1800s.

During these years, Japanese immigration stepped up, and with it, a reactionary anti-Japanese movement joined established anti-Chinese sentiment. During the early 1900s, Japanese numbered less than 3 percent of the total population in California, but nevertheless encountered virulent and sometimes violent racism. The "picture brides" from Japan who emigrated to join their husbands in the U.S. were, to racist Californians, "another example of Oriental treachery," according to historian Roger Daniels.

It bears noting that despite the fact that they weren't in the country in large numbers, Asian women shouldered much of the cost of subsidizing Asian men's labor. U.S. employers didn't have to pay Asian men as much as other laborers who had families to support, since Asian women in Asian bore the costs of rearing children and taking care of the older generation.

Asian women who did emigrate here before the 1960s were also usually employed as cheap labor. In the pre-World War II years, close to half of all Japanese American women were employed as servants or laundresses in the San Francisco area. The World War II internment of Japanese Americans made them especially easy to exploit: they had lost their homes, possessions, and savings when forcibly interned at the camps, Yet, in order to leave, they had to prove they had jobs and homes. U.S. government officials thoughtfully arranged for their employment by fielding requests, most of which were for servants.

Hypersexualization of Asian Women

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=348&height=453)

Asian women have been portrayed as a sexual threat or perpetual sex workers. In fact, before the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in 1882, Asian women were particularly targeted for exclusion in the 1875 Page Act. The act targeted Chinese and other Asian women suspected of prostitution from entering the United States (Schlund-Vials, Wong, and Chang, 2017, p. 38). This is an important example of how a gendered and sexualized framing of the yellow peril stereotype influenced policy that criminalized all Asian female immigrants as undesirable, causing “moral and racial pollution,” and therefore excluded from the U.S. (Lee, 2015, p. 91).

The correlation between Asian women and hypersexuality or sexual deviance continued into the 20th and 21st centuries. One of the first Asian American actresses on the silver screen was Anna May Wong (1905-1961) who was type casted to play “Dragon Lady” characters: deceitful and cunning, but also exotic and sensual women who used their sexuality for foul play. Such representations continued into modern days, such as Lucy Liu’s character on Ally McBeal (1997) and Kill Bill (2003).

When the “model minority” stereotype became prevalent, Asian men were asexualized and deemed effeminate, especially since they were depicted as undermining patriarchal gender roles for doing “women’s work” (i.e. the prevalence of Chinese men doing laundry work). Meanwhile, Asian women were framed as a submissive “Lotus Blossom,” eager to please white men in Hollywood films. Musicals, operas, and movies like Madam Butterfly (1904), Full Metal Jacket (1987), Miss Saigon (1989), Kill Bill: Vol. 1 (2003), The Last Samurai (2003), Memoirs of a Geisha (2005), The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift (2006), and more portrayed Asian female characters in hyper feminine and exotic manners. Asian women have been portrayed as quiet, passive, and subservient, willing to cater to a man’s every whim. These images were rooted in U.S. expansion through wars in Asia, such as the post-WWII U.S. occupation of Japan, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War.

Hollywood films depicting interracial pairings were an endorsement of interracial relationships. However, media critic Dr. Ben Tong notes, “It was a certain form of miscegenation that was endorsed: white man, Asian women, not the reverse” (Gee, 1988, 21:10 - 21:17). These movies romanticized white male/Asian female relations and often overshadowed the very limited opportunities of rural and poor women. Living in the aftermath of the post-war economic destruction of their native countries, women had limited options for work, and were sometimes enticed by American pop culture. Some worked at U.S. military bases as clerks or servers and others entered sex work in order to survive or were tricked into it. Rest and Recreation sites surrounding U.S. military bases in Asia, supported by the U.S. military and local authorities, involved local women to cater to American soldiers. These sites were described as “Playgrounds...for American men fighting in the Korean War, and later camptowns in Korea and Thailand and the Philippines for soldiers fighting in Vietnam” (Kim, 2011, 06:59 - 07:19). In fact, camptowns continued even during peace times, “for today’s American empire is an empire of military bases” (07:18 - 07:26).

The continued popular portrayal of Asian women as “spoils of war,” particularly for American soldiers helped to conflate all Asian women with sex work and hypersexualization, as if it was in our very nature to be sexually alluring and pleasing toward Western men. This was a common portrayal in American films about the war in Vietnam. Movies like Deer Hunter (1978) reinforced the fantasy of the “sexually pleasing Asian woman.” Such portrayals ignore the prevalence of rape, abuse, and killings amongst real Asian sex workers, Asian women and girls who live near and around U.S. military bases, and Asian women married to U.S. servicemen. Some examples of such violence include:

- 1992, South Korea: camptown sex worker Yun Geum-i was sexually assaulted and murdered by private Kenneth Markle

- 1995, Okinawa: three US servicemen kidnapped a 12-year-old local girl, bound her, beat her and took turns raping her

- 2002, South Korea: two 14-year-old girls, Shin Hyo-sun and Shim Mi-seon, were struck and killed by an armored U.S. military vehicle

- 2015, Philippines: Lance Corporal Pemberton was convicted and later pardoned for killing Jennifer Laude, a trans Filipina

Furthermore, in Asian Women United’s documentary, Slaying the Dragon: Reloaded (2011), Asian American Studies professor and author, Elaine H. Kim articulates,

Part of the fantasy about Asian women is that they need to be saved from the East by the West. In fact, saving women from the oppression of Islam and Muslim men has been one of the U.S.’s justifications for invading the Middle East (12:02 - 12:16).

Such framing of Asian women’s sexuality is related to the countless websites, porn sites, massage parlors, and online dating services catering to racist fantasies about sexualized and available Asian women. These prevailing images of Asian women can be connected to why Asian American women reported twice as many hate incidents after COVID-19. The March 16, 2021 slaughter of eight people in Atlanta, Georgia across three Asian massage parlors, with 6 of the victims being Asian American women, is an extension of the normalization of harm and violence toward Asian women that stems from Orientalism, misogyny, anti-immigrant sentiment, and the criminalization of sex workers. The names of the eight killed in the Atlanta mass shooting are: Soon Chung Park, 74; Hyun Jung Grant, 51; Suncha Kim, 69; Yong Ae Yue, 63; Delaina Ashley Yaun Gonzalez, 33; Xiaojie Tan, 49; Daoyou Feng, 44; and Paul Andre Michels, 54 (Nieto Del Rio, Sandoval, Berryman, and Knoll, 2021).

Young, Gay, and APA

Asian Americans who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ) frequently face a double or even triple jeopardy -- being targets of prejudice and discrimination because of their ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation. The following is an article entitled "Young, Gay, and APA," originally published in the July 17, 1999 issue of AsianWeek Magazine, written by Joyce Nishioka. It captures many of the obstacles and challenges that LGBT Asian Americans go through as they search for acceptance and happiness with the multiple forms of their personal identities.

Double Jeopardy

Nineteen-year-old Eric Aquino remembers a day not that long ago when he kneeled down to tie his shoe during P.E. class. He looked up to find a boy towering over him, saying, "That's where you belong" and making a comment about oral sex. "People teased me because they perceived me as a gay, fag queer," he remembers. "What could I do but ignore it? One thing I always did was ignore it."

While feelings of rejection and questions about "being normal" haunt most adolescents, they often hit harder at those who are minorities, either racial or sexual. And too often, those are the kids who get the least support. A 1989 study from the Department of Health and Human Services found that a gay teen who comes out to his or her parents faced about a 50-50 chance of being rejected and 1 in 4 had to leave home. Ten years later, a study in The Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine found that gay and bisexual teens are more than three times as likely to attempt suicide as other youths.

Surveys indicate that 80 percent of gay students do not feel safe in schools, and one poll by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed 1 in 13 high school students had been attacked or harassed because they were perceived to be homosexual. Nationwide, 18 percent of all gay students are physically injured to the point they require medical treatment, and they are seven times as likely as their straight peers to be threatened with a weapon at school, according to the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network.

Protecting homosexual Asian teens from discrimination requires double-duty measures, advocates say. Ofie Virtucio, a coordinator for AQUA, San Francisco's only citywide organization for gay Asian American teenagers (now known as the API Wellness Center), maintains that they are especially likely to be closeted and ignored. "Asians are the model minorities," she says, describing a common stereotype. "They can't be gay or at risk; they don't commit suicide or self-mutilate." In reality, Kim says, "There are many API youths in the California public school system who are gay or perceived as being gay and face angry discrimination and harassment. And there is nothing to adequately protect them."

As Kwok and thousands of others might attest, to be young, gay and APA is to simultaneously confront the ugly specters of barriers and discrimination that come with being gay in America and those that come with being Asian in America. "With the anti-Asian sentiment, students are harassed more for being Asian because it's more visible than sexuality." says San Francisco school district counselor Crystal Jang.

The Closet is a Lonely Place to Live

"People don't think there are API gays and lesbians," Virtucio says. "There is hardly any research, and no money goes to them." Consequently, no one knows precisely how many of San Francisco's Asian American children are gay. But if the often quoted figure of 10 percent of a population holds, the figure could exceed 1,300 in the public junior high and high schools alone. Asian American students, says Jang, account for about 90 percent of the kids she sees through the district's Support Services for Sexual Minorities Youth Program. Though there are more support groups for gay youths than ever before, Virtucio said many Asian American teens find it difficult to fit in. Nor do they have any role models. This decade's most noted gays and lesbians -- actresses Ellen DeGeneres and Anne Heche, Ambassador James Hormel and former Wisconsin congressman Steve Gunderson, Migden and Kuehl -- are all white, and so is society's perception of gay America.

"They can't go to programs for queer gay youths when no one speaks their language," Virtucio says. "How can they be understood when they talk about their close-knit family they can never come out to? They need to see people like them. Even if it's just serving rice, they need something familiar so they could [relate] and feel like they could be part of this community," says Virtucio, who touts her four-year-old group as "a channel to come out." In the summer, 20 to 30 teens -- half of whom are immigrants -- go to AQUA's weekly drop-in sessions. Though the group initially attracted mostly college-age men, most of its members today are younger, and half are female. At a recent get-together, the girls seemed much less vocal than boys, and though several young men agreed to be interviewed, no girls did. Jang explains that girls are more likely than boys to refrain from expressing their sexuality, possibly because of the shame they think they may bring on themselves and their families. One girl, she recalled, fell in love with her godsister and wanted to tell her, but she was afraid that if she did, everyone in Chinatown would find out.

For both genders, though, coming out to family and friends is a huge issue, one that Virtucio says cannot be put off indefinitely. "Parents want to know," she said, adding that many AQUA members have told her that they suspected that their parents knew about their sexuality long before their children would admit it to themselves. Mothers, she said, might ask daughters questions like, "Why to you dress that way? Wear a skirt." Or they might tell their sons, "Don't walk like that." At the same time, she said, cultural pressures to put the family first or to hide one's feelings often convince Asian and Asian American youth to internalize their sexuality. Each family member often is expected to fill an explicit role. For example, she explained, a Filipina, particularly the first-born daughter, "is supposed to take care of the family, and get married and have kids." A first-born Chinese son, she added, "can never be gay. He is supposed to extend the family name."

Desmond Kwok says his parents accept his sexual orientation -- though they don't necessarily support him emotionally. He acknowledges an ongoing "starvation for love" that he blames on his parents. Both have been distant, he says, especially his father, a businessman who lives in Chicago. Kwok says he found support for coming out not from his family, but from a gang he was in two years ago. "They were really cool with it, and it boosted my confidence in the whole coming-out process," he said. "They'd say, 'If someone has a grudge against you for being gay, we're there for you. We'll kick their asses.' "

Now, Kwok dates "older" Asian and Asian American men -- at least 19 -- because few come out before then, he says. He admits that he has tried to find boyfriends over the Internet, at bars and cafes, "the worst places to meet a good boyfriend. A graduate of the School of the Arts, a magnet academy, Kwok said he intends to continue his work as an advocate for gay Asian and Asian American teens. Yet even now he cannot rid "the feeling of being alone -- being around people who really love you, but still knowing they are heterosexual. They'll be with their girlfriends or boyfriends, and here I am all alone, sitting around, boo-hoo, no boyfriend."

'Straight' Into Isolation, 'Out' Into Happiness

Eric Aquino never had such peer support growing up in Vallejo, Calif., and especially in junior high school. "I felt alone," Aquino said. He avoided his locker, where the popular kids hung out, and instead took long, circuitous paths to classes to dodge their cruel comments. "A good day for me was being able to walk down the hall without having anyone ask, 'Are you gay? Do you suck dick?' His grades fell. "I would be late to class and wouldn't bring my books," he explained. "I couldn't concentrate. I looked at the clock until it was 3 o'clock and time to go."

Aquino's high school years were both the happiest and one of the most depressing times of his life. He joined marching band and had friends for the first time, but he also started feeling that he was, in fact, gay. "Friends were important to me because I never had any, but they didn't know me for what I was," he said. Aquino thought perhaps he should wait until he was 18 to come out, so that if his parents rejected him, he could run away. He also considered living in the closet and spent much of his time thinking of ways to keep his secret. "I thought of different alternatives, other options. Like, I'll get married and have kids, [then divorce] and be a single parent, and my parents would just think I never found love again."

Thinking Sociologically

Once LGBTQ Asian Americans come out of the closet, do they find more support and acceptance within the mainstream LGBTQ community? Many do, but unfortunately, anti-Asian racism among the predominantly white LGBTQ community still exists. Joseph Erbentraut's article "Gay Anti-Asian Prejudice Thrives On the Internet " and Gay.net's article "Gay Racism Comes Out" provide insight into the challenges that LGBTQ Asian Americans face with regards to acceptance in the larger LGBTQ community. How are LGBTQ Asian Americans treated in the LGBTQ community in your city?

Ofiee Virtucio, 21, can relate to the feeling of isolation. "Maybe it's the feeling where you know you're Asian but sometimes in situations you're embarrassed to be," she said. "That's where I was for a long time. Of course I was lonely." When she was 13 and still in the Philippines, she recalls, her mother asked her, "Tomboy ca ba?' -- are you gay? She looked me in the eyes; she was worried," Virtucio said. "I said, 'No!' " She wishes that her mom had replied, "Whatever you are, it's OK. I still love you, Ofie.' " Two years later, the family came to the United States. "I had to be white in a month," she recalled. "When I started talking, I had an American accent that I could use, so I could make friends," she said. "During senior year, I was in denial being Filipino and didn't talk about being gay. Most importantly, I had to get friends. I had to get to know what America is all about. I had to survive."

She recalled: "I was trying to be straight but didn't want to have sex. I didn't want a man's penis in me." Though she had a boyfriend in high school, she secretly had crushes on girls, especially the teenage lesbians who were "out." At the same time, she recalls, she "couldn't relate. They were more 'we're-here-we're-queer' ... I knew I was gay, but I thought, 'I'm not like that.' It made me think I could never be like that." So, she said, "When my friends would talk about cute guys, I would jump into the conversation. I thought, 'OK, I have to do this right now,' so I'd say things like, 'Oh, he's so cute.' "Then when I would go home, I'd be like ... oh," said Virtucio, covering her eyes with her palms. "It hurts. It really, really hurts."

Virtucio finally acknowledged her sexuality during her college years, "the happiest time in my life." At age 18, she found her first girlfriend and experienced her first kiss, but it took many more years before she felt truly comfortable about being a lesbian. "I knew it was going to be a hard life," she said. "I thought, 'How am I going to tell my siblings? How am I going to get a job? Am I going to be constrained to having only gay friends? What are people going to think of me? I thought people would know now -- just because I know I'm gay -- that they'll just see it."

Virtucio never had the opportunity to come out to her mother, who passed away when she was 15. But in college, she did tell her father. She remembers he was in the garden watering plants when he asked her, out of the blue, whether her girlfriend was more than a friend. Startled, Virtucio says she denied it, but later that day, she opened the door to his bedroom and said it was true. They took a walk on the beach after that. "He told me whatever made me happy was fine," Virtucio recalls. "My father used to be mean to my mom, pot-bellied, chauvinistic," she says. "But for some reason he found it in his heart to understand. That moment was amazing for me. I thought if my dad could understand, I really don't care what the world thinks. I'm just going to be the person I am."

Contributors and Attributions

- Tsuhako, Joy. (Cerritos College)

- Gutierrez, Erika. (Santiago Canyon College)

- Asian Nation (Le) (CC BY-NC-ND) adapted with permission