10.1.3: Homo Habilis- The Earliest Members of Our Genus

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 136437

Homo habilis has traditionally been considered the earliest species placed in the genus Homo. However, as we will see, there is substantial disagreement among paleoanthropologists about the fossils classified as Homo habilis, including whether they come from a single or multiple species, or even whether they should be part of the genus Homo at all.

Compared to the australopithecines in the previous chapter, Homo habilis has a somewhat larger brain size–an average of 650 cubic centimeters (cc) compared to less than 500 cc for Australopithecus. Additionally, the skull is more rounded and the face less prognathic. However, the postcranial remains show a body size and proportions similar to Australopithecus.

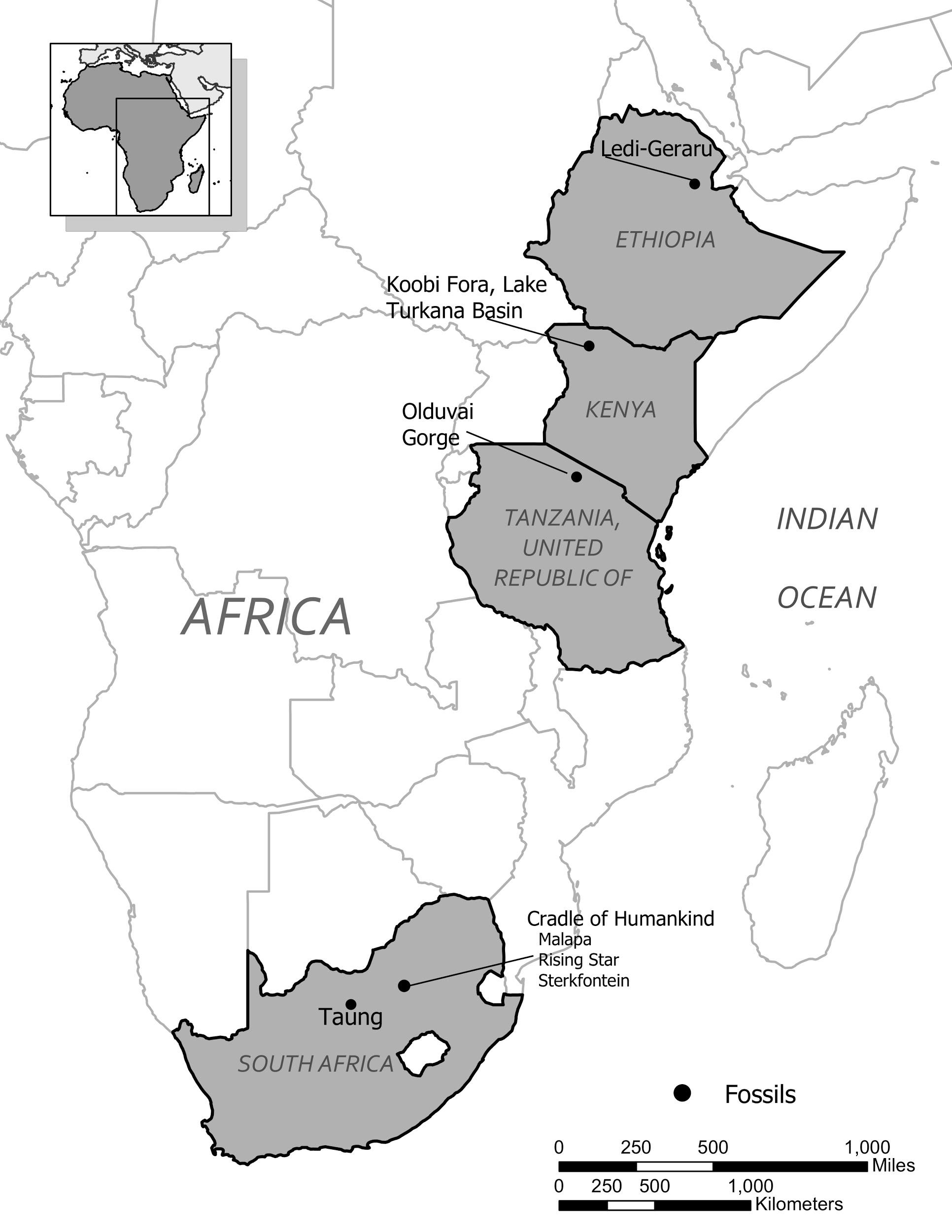

Known dates for fossils identified as Homo habilis range from about 2.5 million years ago to 1.7 million years ago. Recently, a partial lower jaw dated to 2.8 million years from the site of Ledi-Gararu in Ethiopia has been tentatively identified as belonging to the genus Homo (Villmoare et al. 2015). If this classification holds up, it would push the origins of our genus back even further.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Map showing major sites where Homo habilis fossils have been found.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Map showing major sites where Homo habilis fossils have been found.Discovery and Naming

The first fossils to be named Homo habilis were discovered at the site of Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, East Africa, by members of a team led by Louis and Mary Leakey (Fig. 10.4). The Leakey family had been conducting fieldwork in the area since the 1930s and had discovered other hominin fossils at the site, such as the robust Australopithecus boisei. The key specimen, a juvenile individual, was actually found by their 20-year-old son Jonathan Leakey. Louis Leakey invited South African paleoanthropologist Philip Tobias and British anatomist John Napier to reconstruct and analyze the remains. The fossil of the juvenile shown in Figure 10.5 (now known as OH-7) consisted of a lower jaw, parts of the parietal bones of the skull, and some hand and finger bones. Potassium-argon dating of the rock layers showed that the fossil dated to about 1.75 million years. In 1964, the team published their findings in the scientific journal Nature (Leakey et al. 1964). As described in the publication, the new fossils had smaller molar teeth that were less “bulgy” than australopithecine teeth. Although the primary specimen was not yet fully grown, an estimate of its anticipated adult brain size would make it somewhat larger-brained than australopithecines such as A. africanus. The hand bones were similar to humans’ in that they were capable of a precision grip. This increased the likelihood that stone tools found earlier at Olduvai Gorge were made by this group of hominins. Based on these findings, the authors inferred that it was a new species that should be classified in the genus Homo. They gave it the name Homo habilis, meaning “handy” or “skilled.”

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Homo habilis fossil specimens. From left to right they are: OH-24 (found at Olduvai Gorge), KNM-ER-1813 (from Koobi Fora, Kenya), and the jaw of OH-7, which was the type specimen found in 1960 at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Homo habilis fossil specimens. From left to right they are: OH-24 (found at Olduvai Gorge), KNM-ER-1813 (from Koobi Fora, Kenya), and the jaw of OH-7, which was the type specimen found in 1960 at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania.|

Location of Fossils |

Dates |

Description |

|

Ledi-Gararu, Ethiopia |

2.8 mya |

Partial lower jaw with evidence of both Australopithecus and Homo traits; tentatively considered oldest Early Homo fossil evidence. |

|

Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania |

1.7 mya to 1.8 mya |

Several different specimens classified as Homo habilis, including the type specimen found by Leakey, a relatively complete foot, and a skull with a cranial capacity of about 600 cc. |

|

Koobi Fora, Lake Turkana Basin, Kenya |

1.9 mya |

Several fossils from the Lake Turkana basin show considerable size differences, leading some anthropologists to classify the larger specimen (KNM-ER-1470) as a separate species, Homo rudolfensis. |

|

Sterkfontein and other possible South African cave sites |

about 1.7 mya |

South African caves have yielded fragmentary remains identified as Homo habilis, but secure dates and specifics about the fossils are lacking. |

Controversies over Classification of Homo habilis

How Many Species of Homo habilis?

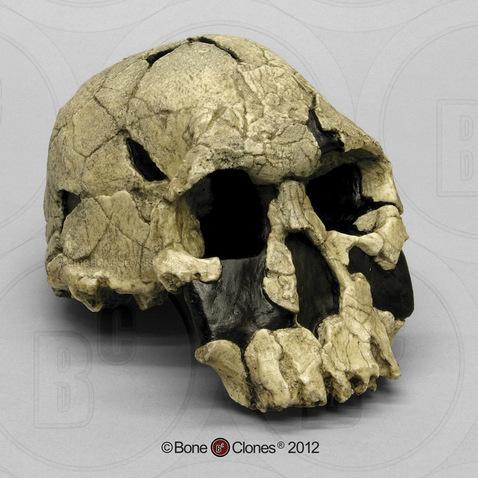

Since this initial discovery, more fossils classified as Homo habilis were discovered in sites in East and South Africa in the 1970s and 1980s (Figure 10.6).. As more fossils joined the ranks of Homo habilis, several trends became apparent. First, the fossils were quite variable. While some resembled the fossil specimen first published by Leakey and colleagues, others had larger cranial capacity and tooth size. A well-preserved fossil skull from East Lake Turkana labeled KNM-ER-1470 displayed a larger cranial size along with a strikingly wide face reminiscent of a robust australopithecine. The diversity of the Homo habilis fossils prompted some scientists to question whether they displayed too much variation to all remain as part of the same species. They proposed splitting the fossils into at least two groups. The first group resembling the original small-brained specimen would retain the species name Homo habilis; the second group consisting of the larger-brained fossils such as KNM-ER-1470 would be assigned the new name of Homo rudolfensis (see Figure 10.7). Researchers who favored keeping all fossils in Homo habilis argued that sexual dimorphism, adaptation to local environments, or developmental plasticity could be the cause of the differences. For example, modern human body size and body proportions are influenced by variations in climates and nutritional circumstances.

Given the incomplete and fragmentary fossil record from this time period, it is not surprising that classification has proved contentious. As a scholarly consensus has not yet emerged on the classification status of early Homo, this text will make use of the single (inclusive) Homo habilis species designation.

Homo habilis: Homo or Australopithecus?

There is also disagreement on whether Homo habilis legitimately belongs in the genus Homo. Most of the fossils first classified as Homo habilis consisted mainly of skulls and teeth. When arm, leg, and foot bones were later found, making it possible to estimate body size, they turned out to be quite small in stature with long arms and short legs. Analysis of the relative strength of limb bones suggested that the species, though bipedal, was much more adapted to arboreal climbing than Homo erectus and Homo sapiens (Ruff 2009). This has prompted some scientists to question whether Homo habilis behaved more like an australopithecine—with a shorter gait and the ability to move around in the trees (Wood and Collard 1999). They also questioned whether the brain size of Homo habilis was really that much larger than that of Australopithecus. They have proposed reclassifying some or all of the Homo habilis fossils into the genus Australopithecus, or even placing them into a newly created genus (Wood 2014).

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Cast of the Homo habilis cranium KNM-ER-1470. This cranium has a wide, flat face, larger brain size, and larger teeth than other Homo habilis fossils, leading some scientists to give it a separate species name, Homo rudolfensis.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Cast of the Homo habilis cranium KNM-ER-1470. This cranium has a wide, flat face, larger brain size, and larger teeth than other Homo habilis fossils, leading some scientists to give it a separate species name, Homo rudolfensis.Other scholars have interpreted the fossil evidence differently. A recent reanalysis of Homo habilis/rudolfensis fossils concluded that they sort into the genus Homo rather than Australopithecus (Figure 10.8). In particular, statistical analysis performed indicates that the Homo habilis fossils differ significantly in average cranial capacity from the australopithecines. They also note that some australopithecine species such as the recently discovered Australopithecus sediba have relatively long legs, so body size may not have been as significant as brain- and tooth-size differences (Anton et al. 2014).

|

Hominin |

Homo habilis |

|

Dates |

2.5 million years ago to 1.7 million years ago |

|

Region(s) |

East and South Africa |

|

Famous Discoveries |

Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania; Koobi Fora, Kenya; Sterkfontein, South Africa |

|

Brain Size |

650 cc average (range from 510 cc to 775 cc) |

|

Dentition |

Smaller teeth with thinner enamel compared to Australopithecus; parabolic dental arcade shape |

|

Cranial Features |

Rounder cranium and less facial prognathism than Australopithecus |

|

Postcranial Features |

Small stature; similar body plan to Australopithecus |

|

Culture |

Oldowan tools |