2.1: The Science of Who We Are and Where We Come From

- Page ID

- 158717

WHO ARE WE?

Fundamental cultural ideas, which organize the world and help to render it meaningful.

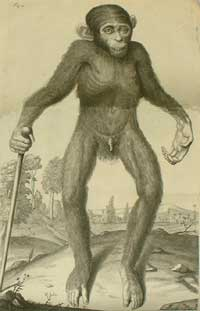

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Tyson’s “orang-outang”.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Tyson’s “orang-outang”.Pre-Darwinian Intellectual Trends

Three general problems were especially vexing to Christian biologists of the 1700s. First, extinction—the loss of a species from the face of the earth—became grudgingly accepted as a fact, even though it seemed to diminish the power and wisdom of God, by making His creation and plan more transient than had traditionally been imagined. Yet not only was there extinction in the present (notably, a bird known as the dodo, hunted and eaten by Dutch colonists on the island of Mauritius, the only place it lived) but there was extinction in the past as well—and a lot of it, the evidence of which was being recovered as fossils. Moreover, the extinctions implied by the fossils were not contemporaneous—the extinctions were patterned, as if different kinds of creatures had lived and died at different times, embedded in distinct geological formations. What might that mean?

The loss of a species from the face of the earth.

The second problem involved a great discovery by the Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus. Where animal species had traditionally been linearly conceptualized in terms of how similar to humans they are—forming a “Great Chain of Being”—Linnaeus identified a distinctly different pattern. After all, there was no clear basis on which to say that an elk is more like a human than a tiger or a walrus is. Linnaeus, rather, argued that species should not be arranged according to how similar they are to us but, rather, by how similar they are to one another. In so doing, in 1758, Linnaeus found that warm-blooded, hairy, lactating vertebrates formed a natural group that he named “Mammalia” (in contrast to, say, fish or birds). Within that group was a cluster of species he called “Primates,” and among them, according to our physical features, was our own species, which he named Homo sapiens. These physical correspondences among diverse kinds of creatures later came to be known as homology. But why did such a pattern of nested similarities exist, and what did it mean?

Correspondence of parts between species due to the mutual inheritance of a primordial form from a common ancestor.

Figure 2.1.3:Ruffed Lemur.

Figure 2.1.3:Ruffed Lemur. Figure 2.1.4:Red Ruffed Lemur.

Figure 2.1.4:Red Ruffed Lemur. Figure 2.1.5: Blue-eyed Black Lemur.

Figure 2.1.5: Blue-eyed Black Lemur.The third problem involved the relationship between adaptation and biogeography. Even though the Bible doesn’t exactly say so, it was understood that animals are adapted to their surroundings because God made them that way. The Bible does say that all living species of animals started out together in the same place—the mountains of Ararat, where Noah’s Ark landed. Yet those animals would not have been adapted to Ararat; so how did polar bears get to the Arctic, koalas to Australia, and bison to the Great Plains, where they are each well adapted, without going extinct first? How could all the lemurs have ended up in Madagascar and nowhere else (see Figures 2.2.2-5)? An explanation for adaptation that was historical, rather than miraculous, would be very valuable.

Any alteration in the structure or functioning of an organism (or group of organisms) that improves its ability to survive and reproduce in its environment.

The geographical distribution of living things.

According to the Bible (Genesis 6–9), God decides to destroy all life because of the wickedness of people, but he saves a righteous man named Noah, his three sons, and their wives. They build a large boat and preserve pairs of all the animals; the boat eventually lands “on the mountains of Ararat” and the world is subsequently repopulated. Other ancient cultures also have relate stories about a flood, boat-builder, and animal-saver, with differing details.

These were the questions that dominated the field of natural history by the beginning of the 1800s. But of course, the big questions of the day weren’t even about fossils or polar bears at all but, rather, about the biopolitics of slavery. Were all people of one stock, the descendants of Adam and Eve? That would seem to afford a moral argument against treating some people as property, if we are all brothers and sisters under the skin, and would seem to accord well with the biblical narrative as well. This position, however, required the development of a biological theory to explain how Adam and Eve’s descendants could have morphed into the diverse peoples of the world. In other words, if you imagined Adam and Eve to be white, then how did black people arise? (Or vice versa.) This position, known as monogenism, was biblical, socially progressive, and generated the earliest modern evolutionary theories—microevolutionary, to be sure, but theories intended to explain the naturalistic production of difference, or what we would now call evolution.

According to the Bible (Genesis 2–3), the first two people are Adam (male) and Eve (female). They inhabit The Garden of Eden, with a Tree of Life and a Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil in the center. They are instructed not to eat the fruit of the latter tree, but they do so anyway and are subsequently cursed and expelled from the garden. This forms the basis for the traditional origin myth of Jews, Muslims, and Christians.

The theory that all humans are descended from the same ancestors.

Others believed that Africans and Europeans shared no common ancestry at all, being the products of separate creations by God. Perhaps in Adam and Eve, the Bible was merely recounting His most recent creation, but the peoples of the rest of the world were fundamentally and unalterably different and had always been so. This position, known as polygenism, was attractive to those looking to rationalize slavery as well as to radical intellectuals who did not feel constrained by biblical literalism.

The discredited theory that humans of different races are descended from different ancestors.

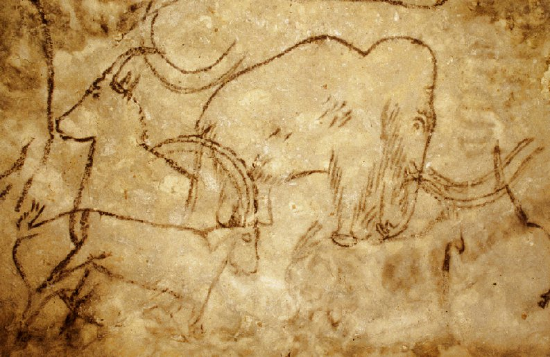

Figure 2.1.6: Cave painting in the Grotte de Rouffignac.

Figure 2.1.6: Cave painting in the Grotte de Rouffignac.By the mid-1800s, the discovery of stone tools in the ground implied a remote period in ancient Europe when the ancestors lived like the “savages” who still used stone tools, whom Europeans were encountering in more remote places of the world. This in turn implied an ancient European “stone age” before the invention of metals, which, like many of the new discoveries, was not part of the information in the Bible. It was increasingly becoming apparent that a long time ago, very primitive Europeans had lived with some extinct animals, like woolly mammoths. They even drew pictures of the extinct animals on the walls of their caves (see Figure 2.1.6).

Savage is a dehumanizing term used by pre-modern European scholars to suggest that other cultures were primitive, violent, immoral, and illogical.

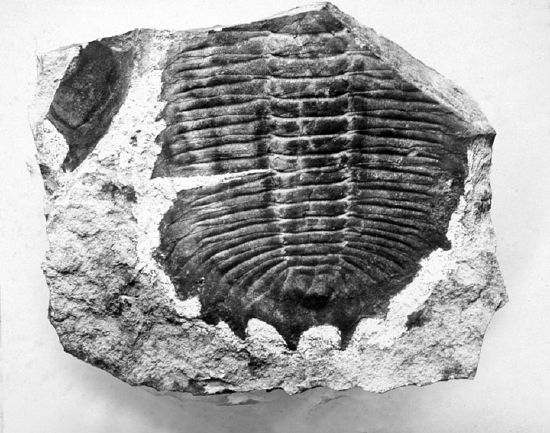

Figure 2.1.7:Trilobite fossil.

Figure 2.1.7:Trilobite fossil.Further, even a Stone Age seemed relatively recent in the larger context of the new geology. All those extinct fossil remains were being found in geological formations far more ancient than any known human evidence (see Figure 2.1.7). Just how ancient was not very clear, but judging by the pace of geological processes we can see today, those processes seem to have been going on for a very, very long time. You simply can’t get fossilization or fossil fuels made in the ground over the few thousands of years of biblical time. The most rational interpretation of the geological evidence, argued the Scottish lawyer/geologist Charles Lyell is that the earth is very, very old—thus stimulating a revolution in both geological and ethnological time. Lyell himself argued that the earth was very old in the 1830s but waffled on how old the human species was until the 1860s.

Finally, educated Europeans were taking their biblical stories more and more loosely, as the field of biblical studies matured. The Bible was being understood as a collection of sacred Jewish and early Christian writings composed at different times and selected from a much larger corpus. Thomas Jefferson had privately distinguished between the things Jesus probably said and did and the things Jesus probably did not say and do. In 1835, a German biblical scholar named David Strauss scandalously interpreted the life of Christ without miracles; his work was published in English in 1846, translated by the aspiring novelist Marian Evans (aka George Eliot). We should focus, argued Strauss, on the meaning of the stories of the Bible, not on whether they really happened or not, for their meaning lies in their narrative content, not in their historicity. This launched a revolution in the area of biblical scholarship.

FIGURE ATTRIBUTIONS

Figure 2.1.2 Ring-tailed lemur portrait 2 by Francis C. Franklin is used under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 License.

Figure 2.1.3 Lemur (39490547425) by Mathias Appel has been designated to the public domain (CC0).

Figure 2.1.4 Lemur (26992319228) by Mathias Appel has been designated to the public domain (CC0).

Figure 2.1.5 Blue-eyed black lemur by Clément Bardot is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 License.

Figure 2.1.6 Grotte de Rouff mammut by cave painter is in the public domain.

Figure 2.1.7 Queensland State Archives 2436 Trilobite fossil at the Queensland Museum Brisbane c 1927 by Agriculture And Stock Department, Publicity Branch is in the public domain.