11.3: The Evolution of the Media

- Page ID

- 59711

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the history of major media formats

- Compare important changes in media types over time

- Explain how citizens learn political information from the media

The evolution of the media has been fraught with concerns and problems. Accusations of mind control, bias, and poor quality have been thrown at the media on a regular basis. Yet the growth of communications technology allows people today to find more information more easily than any previous generation. Mass media can be print, radio, television, or Internet news. They can be local, national, or international. They can be broad or limited in their focus. The choices are tremendous.

PRINT MEDIA

Early news was presented to local populations through the print press. While several colonies had printers and occasional newspapers, high literacy rates combined with the desire for self-government made Boston a perfect location for the creation of a newspaper, and the first continuous press was started there in 1704.[1] Newspapers spread information about local events and activities. The Stamp Tax of 1765 raised costs for publishers, however, leading several newspapers to fold under the increased cost of paper. The repeal of the Stamp Tax in 1766 quieted concerns for a short while, but editors and writers soon began questioning the right of the British to rule over the colonies. Newspapers took part in the effort to inform citizens of British misdeeds and incite attempts to revolt. Readership across the colonies increased to nearly forty thousand homes (among a total population of two million), and daily papers sprang up in large cities.[2]

Although newspapers united for a common cause during the Revolutionary War, the divisions that occurred during the Constitutional Convention and the United States’ early history created a change. The publication of the Federalist Papers, as well as the Anti-Federalist Papers, in the 1780s, moved the nation into the party press era, in which partisanship and political party loyalty dominated the choice of editorial content. One reason was cost. Subscriptions and advertisements did not fully cover printing costs, and political parties stepped in to support presses that aided the parties and their policies. Papers began printing party propaganda and messages, even publicly attacking political leaders like George Washington. Despite the antagonism of the press, Washington and several other founders felt that freedom of the press was important for creating an informed electorate. Indeed, freedom of the press is enshrined in the Bill of Rights in the first amendment.

Between 1830 and 1860, machines and manufacturing made the production of newspapers faster and less expensive. Benjamin Day’s paper, the New York Sun, used technology like the linotype machine to mass-produce papers. Roads and waterways were expanded, decreasing the costs of distributing printed materials to subscribers. New newspapers popped up. The popular penny press papers and magazines contained more gossip than news, but they were affordable at a penny per issue. Over time, papers expanded their coverage to include racing, weather, and educational materials. By 1841, some news reporters considered themselves responsible for upholding high journalistic standards, and under the editor (and politician) Horace Greeley, the New-York Tribune became a nationally respected newspaper. By the end of the Civil War, more journalists and newspapers were aiming to meet professional standards of accuracy and impartiality.[3]

Yet readers still wanted to be entertained. Joseph Pulitzer and the New York World gave them what they wanted. The tabloid-style paper included editorial pages, cartoons, and pictures, while the front-page news was sensational and scandalous. This style of coverage became known as yellow journalism. Ads sold quickly thanks to the paper’s popularity, and the Sunday edition became a regular feature of the newspaper. As the New York World’s circulation increased, other papers copied Pulitzer’s style in an effort to sell papers. Competition between newspapers led to increasingly sensationalized covers and crude issues.

In 1896, Adolph Ochs purchased the New York Times with the goal of creating a dignified newspaper that would provide readers with important news about the economy, politics, and the world rather than gossip and comics. The New York Times brought back the informational model, which exhibits impartiality and accuracy and promotes transparency in government and politics. With the arrival of the Progressive Era, the media began muckraking: the writing and publishing of news coverage that exposed corrupt business and government practices. Investigative work like Upton Sinclair’s serialized novel The Jungle led to changes in the way industrial workers were treated and local political machines were run. The Pure Food and Drug Act and other laws were passed to protect consumers and employees from unsafe food processing practices. Local and state government officials who participated in bribery and corruption became the centerpieces of exposés.

Some muckraking journalism still appears today, and the quicker movement of information through the system would seem to suggest an environment for yet more investigative work and the punch of exposés than in the past. However, at the same time there are fewer journalists being hired than there used to be. The scarcity of journalists and the lack of time to dig for details in a 24-hour, profit-oriented news model make investigative stories rare.[4] There are two potential concerns about the decline of investigative journalism in the digital age. First, one potential shortcoming is that the quality of news content will become uneven in depth and quality, which could lead to a less informed citizenry. Second, if investigative journalism in its systematic form declines, then the cases of wrongdoing that are the objects of such investigations would have a greater chance of going on undetected.

In the twenty-first century, newspapers have struggled to stay financially stable. Print media earned $44.9 billion from ads in 2003, but only $16.4 billion from ads in 2014.[5] Given the countless alternate forms of news, many of which are free, newspaper subscriptions have fallen. Advertising and especially classified ad revenue dipped. Many newspapers now maintain both a print and an Internet presence in order to compete for readers. The rise of free news blogs, such as the Huffington Post, have made it difficult for newspapers to force readers to purchase online subscriptions to access material they place behind a digital paywall. Some local newspapers, in an effort to stay visible and profitable, have turned to social media, like Facebook and Twitter. Stories can be posted and retweeted, allowing readers to comment and forward material.[6] Yet, overall, newspapers have adapted, becoming leaner—though less thorough and investigative—versions of their earlier selves.

RADIO

Radio news made its appearance in the 1920s. The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) and the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) began running sponsored news programs and radio dramas. Comedy programs, such as Amos ’n’ Andy, The Adventures of Gracie, and Easy Aces, also became popular during the 1930s, as listeners were trying to find humor during the Depression. Talk shows, religious shows, and educational programs followed, and by the late 1930s, game shows and quiz shows were added to the airwaves. Almost 83 percent of households had a radio by 1940, and most tuned in regularly.[7]

Not just something to be enjoyed by those in the city, the proliferation of the radio brought communications to rural America as well. News and entertainment programs were also targeted to rural communities. WLS in Chicago provided the National Farm and Home Hour and the WLS Barn Dance. WSM in Nashville began to broadcast the live music show called the Grand Ole Opry, which is still broadcast every week and is the longest live broadcast radio show in U.S. history.[8]

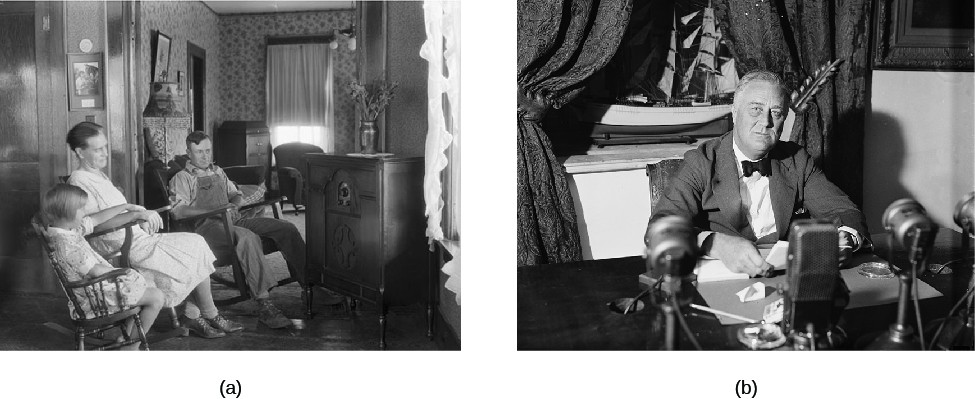

As radio listenership grew, politicians realized that the medium offered a way to reach the public in a personal manner. Warren Harding was the first president to regularly give speeches over the radio. President Herbert Hoover used radio as well, mainly to announce government programs on aid and unemployment relief.[9] Yet it was Franklin D. Roosevelt who became famous for harnessing the political power of radio. On entering office in March 1933, President Roosevelt needed to quiet public fears about the economy and prevent people from removing their money from the banks. He delivered his first radio speech eight days after assuming the presidency:

“My friends: I want to talk for a few minutes with the people of the United States about banking—to talk with the comparatively few who understand the mechanics of banking, but more particularly with the overwhelming majority of you who use banks for the making of deposits and the drawing of checks. I want to tell you what has been done in the last few days, and why it was done, and what the next steps are going to be.”[10]

Roosevelt spoke directly to the people and addressed them as equals. One listener described the chats as soothing, with the president acting like a father, sitting in the room with the family, cutting through the political nonsense and describing what help he needed from each family member.[11] Roosevelt would sit down and explain his ideas and actions directly to the people on a regular basis, confident that he could convince voters of their value.[12] His speeches became known as “fireside chats” and formed an important way for him to promote his New Deal agenda. Roosevelt’s combination of persuasive rhetoric and the media allowed him to expand both the government and the presidency beyond their traditional roles.[13]

During this time, print news still controlled much of the information flowing to the public. Radio news programs were limited in scope and number. But in the 1940s the German annexation of Austria, conflict in Europe, and World War II changed radio news forever. The need and desire for frequent news updates about the constantly evolving war made newspapers, with their once-a-day printing, too slow. People wanted to know what was happening, and they wanted to know immediately. Although initially reluctant to be on the air, reporter Edward R. Murrow of CBS began reporting live about Germany’s actions from his posts in Europe. His reporting contained news and some commentary, and even live coverage during Germany’s aerial bombing of London. To protect covert military operations during the war, the White House had placed guidelines on the reporting of classified information, making a legal exception to the First Amendment’s protection against government involvement in the press. Newscasters voluntarily agreed to suppress information, such as about the development of the atomic bomb and movements of the military, until after the events had occurred.[14]

The number of professional and amateur radio stations grew quickly. Initially, the government exerted little legislative control over the industry. Stations chose their own broadcasting locations, signal strengths, and frequencies, which sometimes overlapped with one another or with the military, leading to tuning problems for listeners. The Radio Act (1927) created the Federal Radio Commission (FRC), which made the first effort to set standards, frequencies, and license stations. The Commission was under heavy pressure from Congress, however, and had little authority. The Communications Act of 1934 ended the FRC and created the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which continued to work with radio stations to assign frequencies and set national standards, as well as oversee other forms of broadcasting and telephones. The FCC regulates interstate communications to this day. For example, it prohibits the use of certain profane words during certain hours on public airwaves.

Prior to WWII, radio frequencies were broadcast using amplitude modulation (AM). After WWII, frequency modulation (FM) broadcasting, with its wider signal bandwidth, provided clear sound with less static and became popular with stations wanting to broadcast speeches or music with high-quality sound. While radio’s importance for distributing news waned with the increase in television usage, it remained popular for listening to music, educational talk shows, and sports broadcasting. Talk stations began to gain ground in the 1980s on both AM and FM frequencies, restoring radio’s importance in politics. By the 1990s, talk shows had gone national, showcasing broadcasters like Rush Limbaugh and Don Imus.

In 1990, Sirius Satellite Radio began a campaign for FCC approval of satellite radio. The idea was to broadcast digital programming from satellites in orbit, eliminating the need for local towers. By 2001, two satellite stations had been approved for broadcasting. Satellite radio has greatly increased programming with many specialized offerings, such as channels dedicated to particular artists. It is generally subscription-based and offers a larger area of coverage, even to remote areas such as deserts and oceans. Satellite programming is also exempt from many of the FCC regulations that govern regular radio stations. Howard Stern, for example, was fined more than $2 million while on public airwaves, mainly for his sexually explicit discussions.[15] Stern moved to Sirius Satellite in 2006 and has since been free of oversight and fines.

TELEVISION

Television combined the best attributes of radio and pictures and changed media forever. The first official broadcast in the United States was President Franklin Roosevelt’s speech at the opening of the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. The public did not immediately begin buying televisions, but coverage of World War II changed their minds. CBS reported on war events and included pictures and maps that enhanced the news for viewers. By the 1950s, the price of television sets had dropped, more televisions stations were being created, and advertisers were buying up spots.

As on the radio, quiz shows and games dominated the television airwaves. But when Edward R. Murrow made the move to television in 1951 with his news show See It Now, television journalism gained its foothold. As television programming expanded, more channels were added. Networks such as ABC, CBS, and NBC began nightly newscasts, and local stations and affiliates followed suit.

Even more than radio, television allows politicians to reach out and connect with citizens and voters in deeper ways. Before television, few voters were able to see a president or candidate speak or answer questions in an interview. Now everyone can decode body language and tone to decide whether candidates or politicians are sincere. Presidents can directly convey their anger, sorrow, or optimism during addresses.

The first television advertisements, run by presidential candidates Dwight D. Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson in the early 1950s, were mainly radio jingles with animation or short question-and-answer sessions. In 1960, John F. Kennedy’s campaign used a Hollywood-style approach to promote his image as young and vibrant. The Kennedy campaign ran interesting and engaging ads, featuring Kennedy, his wife Jacqueline, and everyday citizens who supported him.

Television was also useful to combat scandals and accusations of impropriety. Republican vice presidential candidate Richard Nixon used a televised speech in 1952 to address accusations that he had taken money from a political campaign fund illegally. Nixon laid out his finances, investments, and debts and ended by saying that the only election gift the family had received was a cocker spaniel the children named Checkers.[16] The “Checkers speech” was remembered more for humanizing Nixon than for proving he had not taken money from the campaign account. Yet it was enough to quiet accusations. Democratic vice presidential nominee Geraldine Ferraro similarly used television to answer accusations in 1984, holding a televised press conference to answer questions for over two hours about her husband’s business dealings and tax returns.[17]

In addition to television ads, the 1960 election also featured the first televised presidential debate. By that time most households had a television. Kennedy’s careful grooming and practiced body language allowed viewers to focus on his presidential demeanor. His opponent, Richard Nixon, was still recovering from a severe case of the flu. While Nixon’s substantive answers and debate skills made a favorable impression on radio listeners, viewers’ reaction to his sweaty appearance and obvious discomfort demonstrated that live television had the potential to make or break a candidate.[18] In 1964, Lyndon B. Johnson was ahead in the polls, and he let Barry Goldwater’s campaign know he did not want to debate.[19] Nixon, who ran for president again in 1968 and 1972, declined to debate. Then in 1976, President Gerald Ford, who was behind in the polls, invited Jimmy Carter to debate, and televised debates became a regular part of future presidential campaigns.[20]

LINK TO LEARNING

Visit American Rhetoric for free access to speeches, video, and audio of famous presidential and political speeches.

Between the 1960s and the 1990s, presidents often used television to reach citizens and gain support for policies. When they made speeches, the networks and their local affiliates carried them. With few independent local stations available, a viewer had little alternative but to watch. During this “Golden Age of Presidential Television,” presidents had a strong command of the media.[21]

Some of the best examples of this power occurred when presidents used television to inspire and comfort the population during a national emergency. These speeches aided in the “rally ’round the flag” phenomenon, which occurs when a population feels threatened and unites around the president.[22] During these periods, presidents may receive heightened approval ratings, in part due to the media’s decision about what to cover.[23] In 1995, President Bill Clinton comforted and encouraged the families of the employees and children killed at the bombing of the Oklahoma City Federal Building. Clinton reminded the nation that children learn through action, and so we must speak up against violence and face evil acts with good acts.[24]

Following the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington on September 11, 2001, President George W. Bush’s bullhorn speech from the rubble of Ground Zero in New York similarly became a rally. Bush spoke to the workers and first responders and encouraged them, but his short speech became a viral clip demonstrating the resilience of New Yorkers and the anger of a nation.[25] He told New Yorkers, the country, and the world that Americans could hear the frustration and anguish of New York, and that the terrorists would soon hear the United States.

Following their speeches, both presidents also received a bump in popularity. Clinton’s approval rating rose from 46 to 51 percent, and Bush’s from 51 to 90 percent.[26]

NEW MEDIA TRENDS

The invention of cable in the 1980s and the expansion of the Internet in the 2000s opened up more options for media consumers than ever before. Viewers can watch nearly anything at the click of a button, bypass commercials, and record programs of interest. The resulting saturation, or inundation of information, may lead viewers to abandon the news entirely or become more suspicious and fatigued about politics.[27] This effect, in turn, also changes the president’s ability to reach out to citizens. For example, viewership of the president’s annual State of the Union address has decreased over the years, from sixty-seven million viewers in 1993 to thirty-two million in 2015.[28] Citizens who want to watch reality television and movies can easily avoid the news, leaving presidents with no sure way to communicate with the public.[29] Other voices, such as those of talk show hosts and political pundits, now fill the gap.

Electoral candidates have also lost some media ground. In horse-race coverage, modern journalists analyze campaigns and blunders or the overall race, rather than interviewing the candidates or discussing their issue positions. Some argue that this shallow coverage is a result of candidates’ trying to control the journalists by limiting interviews and quotes. In an effort to regain control of the story, journalists begin analyzing campaigns without input from the candidates.[30] The use of social media by candidates provides a countervailing trend. President Trump’s hundreds of election tweets are the stuff of legend. These tweets kept his press coverage up, although they also were problematic for him at times. The final days of the contest saw no new tweets from Trump as he attempted to stay on message.

The First Social Media Candidate

When president-elect Barack Obama admitted an addiction to his Blackberry, the signs were clear: A new generation was assuming the presidency.[31] Obama’s use of technology was a part of life, not a campaign pretense. Perhaps for this reason, he was the first candidate to fully embrace social media.

While John McCain, the 2008 Republican presidential candidate, focused on traditional media to run his campaign, Obama did not. One of Obama’s campaign advisors was Chris Hughes, a cofounder of Facebook. The campaign allowed Hughes to create a powerful online presence for Obama, with sites on YouTube, Facebook, MySpace, and more. Podcasts and videos were available for anyone looking for information about the candidate. These efforts made it possible for information to be forwarded easily between friends and colleagues. It also allowed Obama to connect with a younger generation that was often left out of politics.

By Election Day, Obama’s skill with the web was clear: he had over two million Facebook supporters, while McCain had 600,000. Obama had 112,000 followers on Twitter, and McCain had only 4,600.[32]

Are there any disadvantages to a presidential candidate’s use of social media and the Internet for campaign purposes? Why or why not?

The availability of the Internet and social media has moved some control of the message back into the presidents’ and candidates’ hands. Politicians can now connect to the people directly, bypassing journalists. When Barack Obama’s minister, the Reverend Jeremiah Wright, was accused of making inflammatory racial sermons in 2008, Obama used YouTube to respond to charges that he shared Wright’s beliefs. The video drew more than seven million views.[33] To reach out to supporters and voters, the White House maintains a YouTube channel and a Facebook site, as did the recent Republican Speaker of the House of Representatives, John Boehner.

Social media, like Facebook, also placed journalism in the hands of citizens: citizen journalism occurs when citizens use their personal recording devices and cell phones to capture events and post them on the Internet. In 2012, citizen journalists caught both presidential candidates by surprise. Mitt Romney was taped by a bartender’s personal camera saying that 47 percent of Americans would vote for President Obama because they were dependent on the government.[34] Obama was recorded by a Huffington Post volunteer saying that some Midwesterners “cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them” due to their frustration with the economy.[35] More recently, as Donald Trump was trying to close out the fall 2016 campaign, his musings about having his way with women were revealed on the infamous Billy Bush Access Hollywood tape. These statements became nightmares for the campaigns. As journalism continues to scale back and hire fewer professional writers in an effort to control costs, citizen journalism may become the new normal.[36]

Another shift in the new media is a change in viewers’ preferred programming. Younger viewers, especially members of Generation X and Millennials, like their newscasts to be humorous. The popularity of The Daily Show and The Colbert Report demonstrate that news, even political news, can win young viewers if delivered well.[37] Such soft news presents news in an entertaining and approachable manner, painlessly introducing a variety of topics. While the depth or quality of reporting may be less than ideal, these shows can sound an alarm as needed to raise citizen awareness.[38]

Viewers who watch or listen to programs like John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight are more likely to be aware and observant of political events and foreign policy crises than they would otherwise be.[39] They may view opposing party candidates more favorably because the low-partisan, friendly interview styles allow politicians to relax and be conversational rather than defensive.[40] Because viewers of political comedy shows watch the news frequently, they may, in fact, be more politically knowledgeable than citizens viewing national news. In two studies researchers interviewed respondents and asked knowledge questions about current events and situations. Viewers of The Daily Show scored more correct answers than viewers of news programming and news stations.[41] That being said, it is not clear whether the number of viewers is large enough to make a big impact on politics, nor do we know whether the learning is long term or short term.[42]

Becoming a Citizen Journalist

Local government and politics need visibility. College students need a voice. Why not become a citizen journalist? City and county governments hold meetings on a regular basis and students rarely attend. Yet issues relevant to students are often discussed at these meetings, like increases in street parking fines, zoning for off-campus housing, and tax incentives for new businesses that employ part-time student labor. Attend some meetings, ask questions, and write about the experience on your Facebook page. Create a blog to organize your reports or use Storify to curate a social media debate. If you prefer videography, create a YouTube channel to document your reports on current events, or Tweet your live video using Periscope or Meerkat.

Not interested in government? Other areas of governance that affect students are the university or college’s Board of Regents meetings. These cover topics like tuition increases, class cuts, and changes to student conduct policies. If your state requires state institutions to open their meetings to the public, consider attending. You might be the one to notify your peers of changes that affect them.

What local meetings could you cover? What issues are important to you and your peers?

Summary

Newspapers were vital during the Revolutionary War. Later, in the party press era, party loyalty governed coverage. At the turn of the twentieth century, investigative journalism and muckraking appeared, and newspapers began presenting more professional, unbiased information. The modern print media have fought to stay relevant and cost-efficient, moving online to do so.

Most families had radios by the 1930s, making it an effective way for politicians, especially presidents, to reach out to citizens. While the increased use of television decreased the popularity of radio, talk radio still provides political information. Modern presidents also use television to rally people in times of crisis, although social media and the Internet now offer a more direct way for them to communicate. While serious newscasts still exist, younger viewers prefer soft news as a way to become informed.

THINK IT OVER

- Why did Franklin D. Roosevelt’s fireside chats help the president enact his policies?

- Why is soft news good at reaching out and educating viewers?

Glossary

- Citizen Journalism

- video and print news posted to the Internet or social media by citizens rather than the news media

- Digital Paywall

- the need for a paid subscription to access published online material

- Muckraking

- news coverage focusing on exposing corrupt business and government practices

- Party Press Era

- period during the 1780s in which newspaper content was biased by political partisanship

- Soft News

- news presented in an entertaining style

- Yellow Journalism

- sensationalized coverage of scandals and human interest stories

- Fellow. American Media History. ↵

- "Population in the Colonial and Continental Periods," http://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/00165897ch01.pdf (November 18, 2015); Fellow. American Media History. ↵

- Fellow. American Media History. ↵

- Lars Willnat and David H. Weaver. 2014. The American Journalist in the Digital Age: Key Findings. Bloomington, IN: School of Journalism, Indiana University. ↵

- Michael Barthel. 29 April 2015. "Newspapers: Factsheet," http://www.journalism.org/2015/04/29/newspapers-fact-sheet/.↵

- "Facebook and Twitter—New but Limited Parts of the Local News System," Pew Research Center, 5 March 2015. ↵

- "1940 Census," http://www.census.gov/1940census (September 6, 2015). ↵

- Steve Craig. 2009. Out of the Dark: A History of Radio and Rural America. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. ↵

- "Herbert Hoover: Radio Address to the Nation on Unemployment Relief," The American Presidency Project, 18 October 1931, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=22855.↵

- "Franklin Delano Roosevelt: First Fireside Chat," http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/fdrfirstfiresidechat.html (August 20, 2015). ↵

- "The Fireside Chats," https://www.history.com/topics/fireside-chats (November 20, 2015); Fellow. American Media History, 256. ↵

- "FDR: A Voice of Hope," http://www.history.com/topics/fireside-chats (September 10, 2015). ↵

- Mary E. Stuckey. 2012. "FDR, the Rhetoric of Vision, and the Creation of a National Synoptic State." Quarterly Journal of Speech 98, No. 3: 297–319. ↵

- Fellow. American Media History. ↵

- Sheila Marikar, "Howard Stern’s Five Most Outrageous Offenses," ABC News, 14 May 2012. ↵

- Lee Huebner, "The Checkers Speech after 60 Years," The Atlantic, 22 September 2012. ↵

- Joel K. Goldstein, "Mondale-Ferraro: Changing History," Huffington Post, 27 March 2011. ↵

- Shanto Iyengar. 2016. Media Politics: A Citizen’s Guide, 3rd ed. New York: W.W. Norton. ↵

- Bob Greene, "When Candidates said ‘No’ to Debates," CNN, 1 October 2012. ↵

- "The Ford/Carter Debates," http://www.pbs.org/newshour/spc/debatingourdestiny/doc1976.html (November 21, 2015); Kayla Webley, "How the Nixon-Kennedy Debate Changed the World," Time, 23 September 2010. ↵

- Matthew A. Baum and Samuel Kernell. 1999. "Has Cable Ended the Golden Age of Presidential Television?" The American Political Science Review 93, No. 1: 99–114. ↵

- Alan J. Lambert1, J. P. Schott1, and Laura Scherer. 2011. "Threat, Politics, and Attitudes toward a Greater Understanding of Rally-’Round-the-Flag Effects," Current Directions in Psychological Science 20, No. 6: 343–348. ↵

- Tim Groeling and Matthew A. Baum. 2008. "Crossing the Water’s Edge: Elite Rhetoric, Media Coverage, and the Rally-Round-the-Flag Phenomenon," Journal of Politics 70, No. 4: 1065–1085. ↵

- "William Jefferson Clinton: Oklahoma Bombing Memorial Prayer Service Address," 23 April 1995, http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/wjcoklahomabombingspeech.htm.↵

- Ian Christopher McCaleb, "Bush tours ground zero in lower Manhattan," CNN, 14 September 2001. ↵

- "Presidential Job Approval Center," http://www.gallup.com/poll/124922/presidential-job-approval-center.aspx (August 28, 2015). ↵

- Alison Dagnes. 2010. Politics on Demand: The Effects of 24-hour News on American Politics. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. ↵

- "Number of Viewers of the State of the Union Addresses from 1993 to 2015 (in millions)," http://www.statista.com/statistics/252425/state-of-the-union-address-viewer-numbers (August 28, 2015). ↵

- Baum and Kernell, "Has Cable Ended the Golden Age of Presidential Television?" ↵

- Shanto Iyengar. 2011. "The Media Game: New Moves, Old Strategies," The Forum: Press Politics and Political Science 9, No. 1, http://pcl.stanford.edu/research/2011/iyengar-mediagame.pdf.↵

- Jeff Zeleny, "Lose the BlackBerry? Yes He Can, Maybe," New York Times, 15 November 2008. ↵

- Matthew Fraser and Soumitra Dutta, "Obama’s win means future elections must be fought online," Guardian, 7 November 2008. ↵

- Iyengar, "The Media Game." ↵

- David Corn. 29 July 2013. "Mitt Romeny’s Incredible 47-Percent Denial," http://www.motherjones.com/mojo/2013/07/mitt-romney-47-percent-denial.↵

- Ed Pilkington, "Obama Angers Midwest Voters with Guns and Religion Remark," Guardian, 14 April 2008. ↵

- Amy Mitchell, "State of the News Media 2015," Pew Research Center, 29 April 2015. ↵

- Tom Huddleston, Jr., "Jon Stewart Just Punched a $250 Million Hole in Viacom’s Value," Fortune, 11 February 2015. ↵

- John Zaller. 2003. "A New Standard of News Quality: Burglar Alarms for the Monitorial Citizen," Political Communication 20, No. 2: 109–130. ↵

- Matthew A. Baum. 2002. "Sex, Lies and War: How Soft News Brings Foreign Policy to the Inattentive Public," American Political Science Review 96, no. 1: 91–109. ↵

- Matthew Baum. 2003. "Soft News and Political Knowledge: Evidence of Absence or Absence of Evidence?" Political Communication 20, No. 2: 173–190. ↵

- "Public Knowledge of Current Affairs Little Changed by News and Information Revolutions," Pew Research Center, 15 April 2007; "What You Know Depends on What You Watch: Current Events Knowledge across Popular News Sources," Fairleigh Dickinson University, 3 May 2012, http://publicmind.fdu.edu/2012/confirmed/.↵

- Markus Prior. 2003. "Any Good News in Soft News? The Impact of Soft News Preference on Political Knowledge," Political Communication 20, No. 2: 149–171. ↵

- American Government 2e. Authored by: OpenStax. Located at: https://cnx.org/contents/nY32AU8S@5.1:xJJkKaSK@5/Preface. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/9d8df601-4f1...50bf739e5f@5.1