8.20: Putting It Together- Sensation and Perception

- Page ID

- 59916

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)In this module, you learned to

- differentiate between sensation and perception

- explain the process of vision and how people see color and depth

- explain the basics of hearing

- describe the basic anatomy and functions of taste, smell, touch, pain, and the vestibular sense

- define perception and give examples of gestalt principles and multimodal perception

In this module, you learned about the way our senses work and the impact they have on our perception of the world. Our impressive sensory abilities allow us to experience the most enjoyable and most miserable experiences, as well as everything in between. Our eyes, ears, nose, tongue and skin provide an interface for the brain to interact with the world around us. While there is simplicity in covering each sensory modality independently, we are organisms that have evolved the ability to process multiple modalities as a unified experience.

While the information covered in this module may initially seem straightforward and stagnant, you saw in the example from Jessica Witt’s research on perception that a person’s perception of the size of a golf hole can impact their performance. The ways that perception can alter our behavior and the impact this has on mental processes is of particular interest to psychologists.

One current area of interest is the influence of psychological principles on virtual reality design. Think about it. How can designers create a 3-dimensional world on a 2-dimensional plane? They must first consider the way that we interpret visual cues and how we see depth. Consider Google Cardboard. In 2014, two Google engineers created a cardboard viewer lens that allows users to place their smartphones inside and view the world as if they entered a virtual reality. This was a huge leap forward in reducing the cost of and increasing access to virtual reality. But how did they do it? In order to feel like you are immersed in the gaming world, you need to remove the distractions that exist outside of the immediate visual field. Hence, the box around the phone. You also need to feel like you are inside of the world, so the box includes lenses that adjust your focal point and magnify the picture on the screen (Figure 1).

You also need the world to be 3-dimensional. As you learned, your eyes rely on several monocular and binocular cues in order to see depth. Binocular disparity describes the slightly unique view of the world we see from each of our two eyes (which explains why if you hold an object near your face and close one eye, then open it and close the other, that object appears to move). To create this effect, developers put a barrier between the left and right visual fields and split the screen in two, so that the image on the screen is slightly different. The picture on your phone shows up like this:

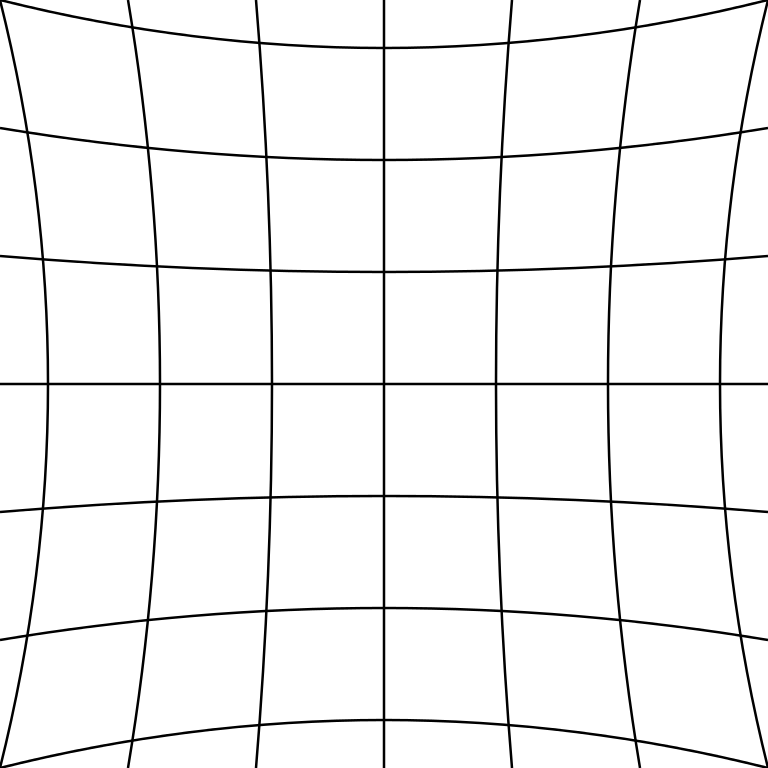

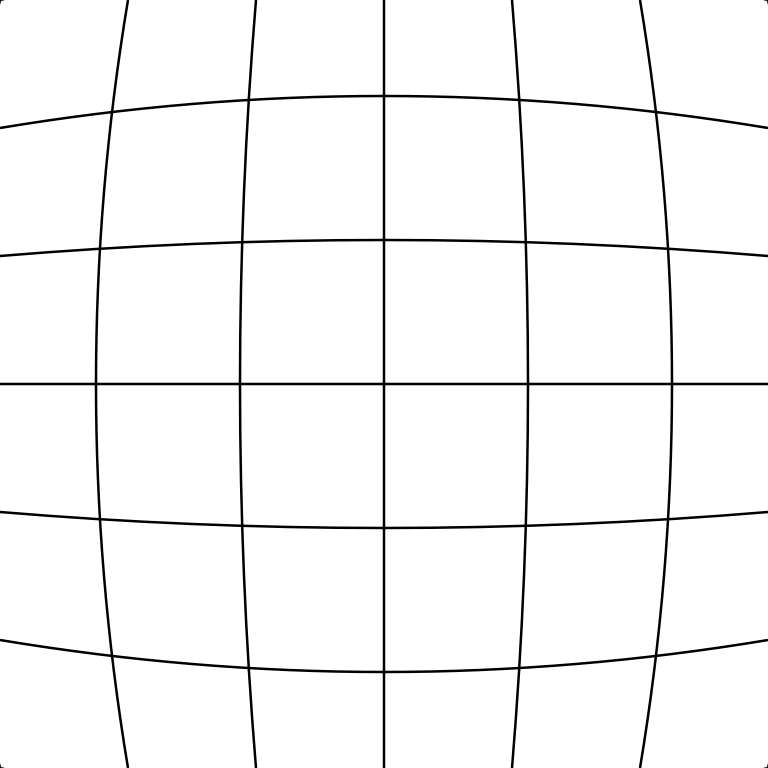

Because you are viewing the image through magnified lenses, there is a distortion called the pincushion distortion, which stretches the image in the corners of the view. To counteract that and make the work appear normal, developers apply a barrel distortion to the viewer, which explains why you see the image in the video with the pinched corners.

Advances in virtual reality are also important to psychology because virtual reality is a treatment method used to help those with psychological disorders. Consider PTSD or phobias, for example. In a virtual world, a counselor can create situations and experiences designed to recreate the triggers for specific behaviors and assist the client in using coping mechanisms to deal with threatening situations. Virtual reality therapy can be used in numerous ways as a type of exposure therapy, even assisting people with autism as they practice recognizing and interpreting social cues or helping those with depression to make choices to help them prevent negative thoughts.

Licenses and Attributions

CC licensed content, Original

- Putting It Together: Sensation and Perception. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Google Cardboard VR with Camera Viewer. Authored by: sndrv. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/sndrv/16905172090. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Distortion images. Authored by: WolfWings. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distortion_(optics). License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Google Cardboard. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Cardboard. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Introductory Paragraph. Authored by: Adam John Privitera . Provided by: Chemeketa Community College. Located at: http://nobaproject.com/modules/sensation-and-perception. Project: The Noba Project. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Google Cardboard image. Authored by: Evan Amos. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Cardboard#/media/File:Google-Cardboard.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright