13.13: Attraction and Love

- Page ID

- 59993

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Describe attraction and the triangular theory of love

- Explain the social exchange theory as it applies to relationships

Forming Relationships

What do you think is the single most influential factor in determining with whom you become friends and whom you form romantic relationships? You might be surprised to learn that the answer is simple: the people with whom you have the most contact. This most important factor is proximity. You are more likely to be friends with people you have regular contact with. For example, there are decades of research that shows that you are more likely to become friends with people who live in your dorm, your apartment building, or your immediate neighborhood than with people who live farther away (Festinger, Schachler, & Back, 1950). It is simply easier to form relationships with people you see often because you have the opportunity to get to know them.

One of the reasons why proximity matters to attraction is that it breeds familiarity; people are more attracted to that which is familiar. Just being around someone or being repeatedly exposed to them increases the likelihood that we will be attracted to them. We also tend to feel safe with familiar people, as it is likely we know what to expect from them. Dr. Robert Zajonc (1968) labeled this phenomenon the mere-exposure effect. More specifically, he argued that the more often we are exposed to a stimulus (e.g., sound, person) the more likely we are to view that stimulus positively. Moreland and Beach (1992) demonstrated this by exposing a college class to four women (similar in appearance and age) who attended different numbers of classes, revealing that the more classes a woman attended, the more familiar, similar, and attractive she was considered by the other students.

There is a certain comfort in knowing what to expect from others; consequently research suggests that we like what is familiar. While this is often on a subconscious level, research has found this to be one of the most basic principles of attraction (Zajonc, 1980). For example, a young man growing up with an overbearing mother may be attracted to other overbearing women not because he likes being dominated but rather because it is what he considers normal (i.e., familiar).

Similarity is another factor that influences who we form relationships with. We are more likely to become friends or lovers with someone who is similar to us in background, attitudes, and lifestyle. In fact, there is no evidence that opposites attract. Rather, we are attracted to people who are most like us (Figure 1) (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001). Why do you think we are attracted to people who are similar to us? Sharing things in common will certainly make it easy to get along with others and form connections. When you and another person share similar music taste, hobbies, food preferences, and so on, deciding what to do with your time together might be easy. Homophily is the tendency for people to form social networks, including friendships, marriage, business relationships, and many other types of relationships, with others who are similar (McPherson et al., 2001).

But, homophily limits our exposure to diversity (McPherson et al., 2001). By forming relationships only with people who are similar to us, we will have homogenous groups and will not be exposed to different points of view. In other words, because we are likely to spend time with those who are most like ourselves, we will have limited exposure to those who are different than ourselves, including people of different races, ethnicities, social-economic status, and life situations.

Once we form relationships with people, we desire reciprocity. Reciprocity is the give and take in relationships. We contribute to relationships, but we expect to receive benefits as well. That is, we want our relationships to be a two way street. We are more likely to like and engage with people who like us back. Self-disclosure is part of the two way street. Self-disclosure is the sharing of personal information (Laurenceau, Barrett, & Pietromonaco, 1998). We form more intimate connections with people with whom we disclose important information about ourselves. Indeed, self-disclosure is a characteristic of healthy intimate relationships, as long as the information disclosed is consistent with our own views (Cozby, 1973).

Try It

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Attraction

We have discussed how proximity and similarity lead to the formation of relationships, and that reciprocity and self-disclosure are important for relationship maintenance. But, what features of a person do we find attractive? We don’t form relationships with everyone that lives or works near us, so how is it that we decide which specific individuals we will select as friends and lovers?

Researchers have documented several characteristics in men and women that humans find attractive. First we look for friends and lovers who are physically attractive. People differ in what they consider attractive, and attractiveness is culturally influenced. Research, however, suggests that some universally attractive features in women include large eyes, high cheekbones, a narrow jaw line, a slender build (Buss, 1989), and a lower waist-to-hip ratio (Singh, 1993). For men, attractive traits include being tall, having broad shoulders, and a narrow waist (Buss, 1989). Both men and women with high levels of facial and body symmetry are generally considered more attractive than asymmetric individuals (Fink, Neave, Manning, & Grammer, 2006; Penton-Voak et al., 2001; Rikowski & Grammer, 1999). Social traits that people find attractive in potential female mates include warmth, affection, and social skills; in males, the attractive traits include achievement, leadership qualities, and job skills (Regan & Berscheid, 1997). Although humans want mates who are physically attractive, this does not mean that we look for the most attractive person possible. In fact, this observation has led some to propose what is known as the matching hypothesis which asserts that people tend to pick someone they view as their equal in physical attractiveness and social desirability (Taylor, Fiore, Mendelsohn, & Cheshire, 2011). For example, you and most people you know likely would say that a very attractive movie star is out of your league. So, even if you had proximity to that person, you likely would not ask them out on a date because you believe you likely would be rejected. People weigh a potential partner’s attractiveness against the likelihood of success with that person. If you think you are particularly unattractive (even if you are not), you likely will seek partners that are fairly unattractive (that is, unattractive in physical appearance or in behavior).

Link to Learning

Learn more about attraction and beauty at The Noba Project website.

Try It

Query \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Sternberg’s Triangular Theory of Love

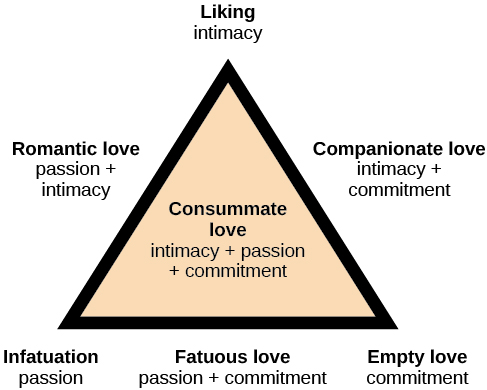

We typically love the people with whom we form relationships, but the type of love we have for our family, friends, and lovers differs. Robert Sternberg (1986) proposed that there are three components of love: intimacy, passion, and commitment. These three components form a triangle that defines multiple types of love: this is known as Sternberg’s triangular theory of love (Figure 2). Intimacy is the sharing of details and intimate thoughts and emotions. Passion is the physical attraction—the flame in the fire. Commitment is standing by the person—the “in sickness and health” part of the relationship.

Sternberg (1986) states that a healthy relationship will have all three components of love—intimacy, passion, and commitment—which is described as consummate love (Figure 3). However, different aspects of love might be more prevalent at different life stages. Other forms of love include liking, which is defined as having intimacy but no passion or commitment. Infatuation is the presence of passion without intimacy or commitment. Empty love is having commitment without intimacy or passion. Companionate love, which is characteristic of close friendships and family relationships, consists of intimacy and commitment but no passion. Romantic love is defined by having passion and intimacy, but no commitment. Finally, fatuous love is defined by having passion and commitment, but no intimacy, such as a long term sexual love affair. Can you describe other examples of relationships that fit these different types of love?

Taking this theory a step further, anthropologist Helen Fisher explained that she scanned the brains (using fMRI) of people who had just fallen in love and observed that their brain chemistry was “going crazy,” similar to the brain of an addict on a drug high (Cohen, 2007). Specifically, serotonin production increased by as much as 40% in newly in-love individuals. Further, those newly in love tended to show obsessive-compulsive tendencies. Conversely, when a person experiences a breakup, the brain processes it in a similar way to quitting a heroin habit (Fisher, Brown, Aron, Strong, & Mashek, 2009). Thus, those who believe that breakups are physically painful are correct! Another interesting point is that long-term love and sexual desire activate different areas of the brain. More specifically, sexual needs activate the part of the brain that is particularly sensitive to innately pleasurable things such as food, sex, and drugs (i.e., the striatum—a rather simplistic reward system), whereas love requires conditioning—it is more like a habit. When sexual needs are rewarded consistently, then love can develop. In other words, love grows out of positive rewards, expectancies, and habit (Cacioppo, Bianchi-Demicheli, Hatfield & Rapson, 2012).

Link to Learning

Watch this TED talk by Helen Fisher to learn more about the brain in love.

Try It

Query \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Social Exchange Theory

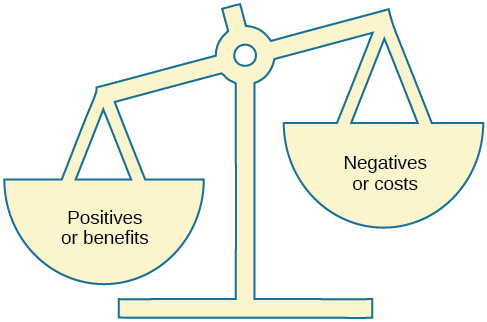

We have discussed why we form relationships, what attracts us to others, and different types of love. But what determines whether we are satisfied with and stay in a relationship? One theory that provides an explanation is social exchange theory. According to social exchange theory, we act as naïve economists in keeping a tally of the ratio of costs and benefits of forming and maintaining a relationship with others (Figure 4) (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003).

People are motivated to maximize the benefits of social exchanges, or relationships, and minimize the costs. People prefer to have more benefits than costs, or to have nearly equal costs and benefits, but most people are dissatisfied if their social exchanges create more costs than benefits. Let’s discuss an example. If you have ever decided to commit to a romantic relationship, you probably considered the advantages and disadvantages of your decision. What are the benefits of being in a committed romantic relationship? You may have considered having companionship, intimacy, and passion, but also being comfortable with a person you know well. What are the costs of being in a committed romantic relationship? You may think that over time boredom from being with only one person may set in; moreover, it may be expensive to share activities such as attending movies and going to dinner. However, the benefits of dating your romantic partner presumably outweigh the costs, or you wouldn’t continue the relationship.

Try It

Query \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{6}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{7}\)

Think It Over

- Think about your recent friendships and romantic relationship(s). What factors do you think influenced the development of these relationships? What attracted you to becoming friends or romantic partners?

- Have you ever used a social exchange theory approach to determine how satisfied you were in a relationship, either a friendship or romantic relationship? Have you ever had the costs outweigh the benefits of a relationship? If so, how did you address this imbalance?

Glossary

altruism: humans’ desire to help others even if the costs outweigh the benefits of helping

companionate love: type of love consisting of intimacy and commitment, but not passion; associated with close friendships and family relationships

consummate love: type of love occurring when intimacy, passion, and commitment are all present

empathy: capacity to understand another person’s perspective—to feel what he or she feels

homophily: tendency for people to form social networks, including friendships, marriage, business relationships, and many other types of relationships, with others who are similar

mere-exposure effect: the more often we are exposed to a stimulus (e.g., sound, person) the more likely we are to view that stimulus positively

prosocial behavior: voluntary behavior with the intent to help other people

reciprocity: give and take in relationships

romantic love: type of love consisting of intimacy and passion, but no commitment

self-disclosure: sharing personal information in relationships

social exchange theory: humans act as naïve economists in keeping a tally of the ratio of costs and benefits of forming and maintain a relationship, with the goal to maximize benefits and minimize costs

triangular theory of love: model of love based on three components: intimacy, passion, and commitment; several types of love exist, depending on the presence or absence of each of these components

Contributors and Attributions

CC licensed content, Original

- Modification and adaptation, addition of link to learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Prosocial Behavior. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@5.52:QoyK23PR@5/Prosocial-Behavior. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11629/latest/.

- Paragraph on love and the brain. Authored by: Debi Brannan and Cynthia D. Mohr . Provided by: Western Oregon University, Portland State University. Located at: http://nobaproject.com/textbooks/introduction-to-psychology-the-full-noba-collection/modules/love-friendship-and-social-support. Project: The Noba Project. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Paragraphs on familiarity and the mere exposure effect. Authored by: Debi Brannan and Cynthia D. Mohr. Provided by: Western Oregon University, Portland State University. Located at: http://nobaproject.com/modules/love-friendship-and-social-support. Project: The Noba Project. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike