14.14: Psych in Real Life- Blirtatiousness, Questionnaires, and Validity

- Page ID

- 60014

Learning Objectives

- Describe the complications of developing personality assessments, including the importance of reliability and validity

Creating a Personality Questionnaire

Psychologists often assess a person’s personality using a questionnaire that is filled in by the person who is being assessed. Such a tests is called a “self-report inventory.” To get into the spirit of personality assessment, please complete the personality inventory below. It has only 10 questions. Simply decide much each pair of words or phrases fits you.

Take the TIPI Personality Test

The questionnaire you just completed is called the TIPI: The Ten-Item Personality Inventory. It was created by University of Texas psychologist Sam Gosling as a very brief measure of five personality characteristics: Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional Stability, and Openness to Experience. These five personality dimensions are called “The Big Five” and, taken together, they have been found to be an excellent first-level summary of people’s personality.

Tests of the Big Five personality dimensions are widely used by researchers and by people in business and education who want a general view of a person’s personality. There are several different self-report inventories that have been developed to measure the Big Five traits, most with 50 or more questions. The TIPI, which you just took, was developed for situations where time is very limited and the tester (usually a researcher) needs a “good enough” version of the test. One of the longer versions would be used by someone needing a more reliable and nuanced view of someone’s personality.

Looking at the TIPI, you might have the impression that creating a personality inventory is pretty easy. You come up with a few obvious questions, find names that fit, and you’re ready to claim you are measuring something about people’s personality.

Undoubtedly you can find some “personality tests” on the internet that fit this description, but tests created by serious psychologists for use in research or in clinical settings must go through a much more careful development process before they are widely accepted and used. And, even then, the tests continue to be studied, criticized, and revised.

In this exercise, we will look more closely at some of the work that goes into creating a personality inventory or questionnaire. To help you keep your eyes on the process of test construction, we want you to think about a personality dimension that is not as obvious as self-esteem or extraversion. We are going to assess blirtatiousness.

Part 1: Creating the Blirt Scale

One of my closest friends is sometimes annoying and usually entertaining, but he never holds back; you always know what he’s thinking. His wife is kind and friendly, and she is first to arrive when help is needed, but she hides her feelings and opinions. It is not easy to know what she wants or where she stands.

Consider your own closest friends. Where do they fall on the continuum between my friends? Who is open and easy to read, and who is private and guarded?

Back in the early 2000s, social psychologist William Swann and his colleagues became interested in the impact of self-disclosure—the process of communicating information about ourselves to other people—on personal relationships. In one paper, the researchers wrote about “blirters” and “brooders”—good labels for my two friends. Early in their research, the psychologists realized that the story was not going to be simple. Enthusiastic self-disclosure (blirting) is sometimes good for relationships and sometimes bad, and the same is true about reluctance to self-disclose (brooding).

The researchers also realized that they didn’t really have a good way to sort people out on the self-disclosure continuum. Self-selection (“I’m very open.” “I’m very private.”) often doesn’t fit with how other people—including your friends—see you. And researchers’ first impressions (“He seems like a blirter.” “She seems like a brooder.”) are extremely unreliable. They needed a better way to measure people’s willingness to self-disclose.

In this exercise, we’re going to give you a small taste of the process of creating a personality questionnaire. To do this, we are going to re-create Dr. Swann’s “blirtatiousness” test that is now used by researchers studying self-disclosure in personal relationships.

By the way, even serious psychologists seem to want to give their tests interesting names, so the name BLIRT stands for Brief Loquaciousness and Interpersonal Responsiveness Test.

Scale Construction: What Questions Should We Use?

The first step in constructing a test or scale to measure some personal characteristic is to be clear about what it is you are measuring. In their papers, Dr. Swann and his colleagues discuss what they mean by “blirtatiousness” in detail, but here the following definition should be enough: Blirtatiousness is the extent to which people respond to friends and partners quickly and effusively. A person is effusive if they excitedly show and express emotion.

One thing to notice about this definition is that it focuses on behavior more than inner feelings. It is the behaviors of our friends and partners that affect us, regardless of their intentions and motivations, so that is what the BLIRT scale is all about.

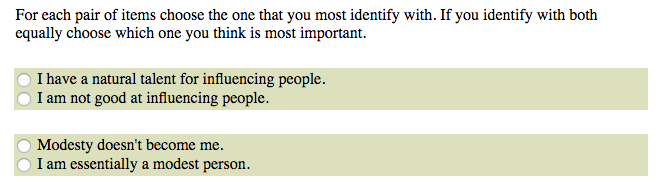

Obviously, the first step in creating a questionnaire is writing the questions, but this is not as straightforward as it seems. Will they be open-ended (e.g., “How open-minded are you? ___). Probably not, as they are hard to score. Forced-choice, where a person chooses one of several options, is a better choice. Some forced-choice questions make you give rankings, or others may have you choose from options, like these questions from the Narcissistic Personality Inventory:

Figure 1. The questions from Terry Raskin’s Narcissistic Personality Inventory force participants to choose between two options.

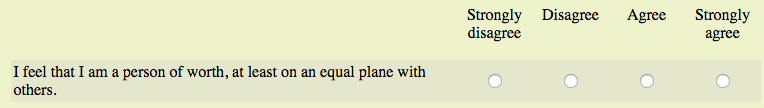

Another common forced-choice format is the Likert[1] scale, which is composed of a statement (not a question) followed by 5 or 7 numbers allowing you to indicate your level of agreement with the statement. For example, here is an item from the Rosenberg Self-Esteem inventory:

Figure 2. Morris Rosenberg’s questions on the self-esteem inventory utilize the Likert scale.

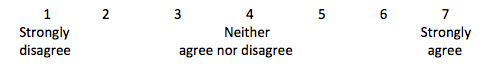

Dr. Swann and his team chose a 7-point Likert format to measure blirtatiousness. To do this, they needed to write clear, simple statements that people could agree or disagree with, where different levels of agreement were possible.

We aren’t going to ask you to write any questions, but join the test-development team by looking at the eight statements below. Choose four that you think would be the best items to include in the BLIRT scale.

Query

When they were developing the scale, Dr. Swann and his team wrote dozens of questions, and then pared them down to 20. Then, they got 237 undergraduates to rate the 20 questions for how well they fit the qualities that the BLIRT scale was trying to measure.[2]

Questionnaire writers have strategies to encourage people to read the statements carefully. For example, they often write “reverse scoring” items. To show what this means, just below is the 7-point Likert scale used with the Blirtatiousness questionnaire. Below that you will see two statements. Look at how the statements and the Likert scale fit together.

Figure 3. A Likert scale.

- I speak my mind as soon as a thought enters my head.

- For this question, 1 means not blirtatious and 7 means very blirtatious.

- I speak my mind as soon as a thought enters my head.

- For this question, 1 means very blirtatious and 7 means not blirtatious.

Dr. Swann and his team chose 8 items for the BLIRT scale and half were worded so that higher numbers mean more blirtatious, and half so that high numbers mean less blirtatious. After the test, a process called “reverse scoring” put all the questions back on the same scale, so that higher numbers mean more blirtatious.[3]

At this point in the test-creation process, Dr. Swann and his team settled on eight statements that seemed to measure BLIRT. They were ready to administer the test, but before they could praise the test and its effectiveness, they needed to be sure of a few things: the questions need to work together as a set, the test must be reliable, and the test must be valid.

- The questions must work together as a set. In other words, we want to be sure that the 8 items are all giving us responses about the same quality (blirtatiousness) and that the responses people are giving are consistent with one another.

- You might think that a single question would be enough to measure blirtatiousness. Why ask 8 questions when one would do? But research has shown that asking variations on the same question 8 or 10 different times gives a more stable measure. The questions must be slightly different (enough to make people think carefully), but not too different (so they measure different things).

- The researchers administered the BLIRT to 1,137 students and used statistical procedures[4] to be sure that the 8 items in the scale worked together. The results indicated that the 8 items on the scale were consistent with each other in measuring the same psychological quality.

- The test must be reliable. The word “reliability” means “consistent.” We should be able to give you a test of some quality (e.g., how extraverted you are) and then give you that same test again two months later, and your scores should be pretty similar. This is important for what are called “stable traits”. Obviously, some psychological qualities, like moods, change all the time and we would not expect consistency. But blirtatiousness should be a stable trait.

- One common way to measure reliability of a test is a process called “test-retest reliability.” It is as simple as it sounds: you give the test, wait some period of time, and give again to the same people.

Try It

Query

- The test must be valid. Believe it or not, after all this work, we still don’t know if the BLIRT scale is VALID. Validity is a question of whether or not we are measuring the thing we are trying to measure. Reliability doesn’t tell us if a scale is valid; reliability simply means that we get consistent answers. So how can we figure out if our test is valid or not? We’ll go into that in the next section.

The exercises you just reviewed give you a taste of the initial steps in creating a personality inventory. We started by carefully defining the personality trait. We had to figure out how we were going to ask our questions, and we chose a Likert scale. The questions had to be carefully written to be clear and focused on the trait we are studying: blirtatiousness. Writing effective items usually involves a process of writing, testing, selection, rewriting, retesting, and selecting again, until we are satisfied that our questions are good. Once we have compiled a test–at least a candidate for the test–we need to administer it to people to see if it is reliable and internally consistent (i.e., that all the questions are measuring the same trait).

Meassuring Personality

Before you go on, now is a good time to measure your blirtatiousness. Follow the link below to find out if you are a blirter or a brooder.

Part 2: Does the Blirt Scale Measure What It Claims to Measure?

No one wants to use a scale that hasn’t been shown to be valid. And validity is really hard to show.

Analyzing Validity

Here is our challenge. Remember that blirtatiousness is the extent to which people respond to friends and partners quickly and effusively. Our questions may look good, but we need evidence that the numbers we get actually measure the trait.

There is no one way to determine the validity of a scale. Test developers like Dr. Swann usually take several different approaches. They may compare the test results with other personality tests of similar traits (convergent validity), or compare scores from the BLIRT test with other dissimilar tests (discriminant validity). Researchers may also compare the results of the BLIRT test to real-world outcomes (criterion validity), or see if the results work to predict people’s behavior in certain situations (predictive validity).

In the sections below, we will peek at some studies that try to assess these different aspects of validity.

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

One way to test the validity of a test is to compare it to results from tests of other traits for which validated tests already exist. There are two types of comparisons that researchers look for when they validate a test. One is called convergent validity and the other is called discriminant validity.

When testing for convergent validity, the researcher looks for other traits that are similar to (but not identical to) the trait they are measuring. For example, we are studying blirtatiousness. It would be reasonable to think that a person who is blirtatious is also assertive. The two traits—blirtatiousness and assertiveness—are not the same, but they are certainly related. If our blirtatiousness scale is not at all related to assertiveness, then we should be worried that we are not really measuring blirtatiousness successfully.

We can use the correlation between the BLIRT score and a score on a test of assertiveness to measure convergent validity. The researchers gave a set of tests, including the BLIRT scale and a measure of assertiveness[5] to 1,397 college students. Assertiveness was just one of several traits that were expected to be similar to blirtatiousness.[6]

Try It

Query

We want our BLIRT score to have a moderate-to-strong relationship with traits that are similar, but we also want it to be unrelated to traits or abilities that are not similar to blirtatiousness. Tests of discriminant validity compare our BLIRT score to traits that should have weak or no relationship to blirtatiousness. For example, people who are blirtatious may be good students or poor students or somewhere in-between. Knowing how blirtatious you are should not tell us much about how good a student you are.

The researchers compared the BLIRT score of the 1,397 students mentioned earlier to their self-reported GPA.[7]

Try It

Query

Dr. Swann’s team compared 21 different traits and abilities to the blirtatiousness scale. Some assessed convergent validity and others tested discriminant validity. The results were generally convincing: BLIRT scores were similar to traits that should be related to blirtatiousness (good convergent validity) and unrelated to traits that should have no connection to blirtatiousness (good discriminant validity).

Criterion Validity

Another way to test the validity of a measure is to see if it fits the way people behave in the real world. The BLIRT researchers conducted two studies to see if BLIRT scores fit what we know about people’s personalities. Criterion validity is the relationship between some measure and some real-world outcome.

Librarians or Salespeople?

Who do you think is more likely to be blirtatious, a salesperson or a librarian? The researchers found thirty employees of car dealerships and libraries in central Texas and gave them the BLIRT scale. Their ages ranged from 20 to 66 (average age = 34.3 years).

Try It

Using the bar graph below, adjust the bars based on your prediction about who will be more blirtatious. Then click the link below to see if your prediction is correct.

Query

Most people expect salespeople to be more blirtatious than librarians. The researchers explained that we assume that high blirters will look for a work environment that rewards “effusive, rapid responding,” while low blirters would prefer a workplace that encourages “reflection and social inhibition.” As you can see, the results of the study were consistent with this idea: salespeople had significantly higher blirt scores (on the average) than librarians.

Asian Americans or European Americans?

How blirtatious a person is can be influenced by a lot of factors, including “cultural norms”—ways of acting that we learn from our families and the people around us as we grow up. Although we shouldn’t overstate the difference, Asian cultures tend to emphasize restraint of emotional expression, while European cultures are more likely to encourage direct and rapid expression.

The researchers were able to get BLIRT scores from 2,800 students from European-American cultures and 698 students from Asian-American cultures. What would you predict about the BLIRT scores for these two groups?

Try It

Using the bar graph below, adjust the bars based on your prediction about who will be more blirtatious. Then click the link below to see if your prediction is correct.

Query

As you can see, the results were consistent with the researchers’ expectations. The difference between the groups was small, but statistically significant. The small difference indicates that we shouldn’t turn these modest differences into cultural stereotypes, but the statistically significant difference suggests that cultural experiences may have a real—if modest—effect on people’s blirtatiousness.

Predictive Validity

Another way to assess validity of the BLIRT scale is to see if it predicts people’s behavior in specific situations. Based on research about first impressions, the experimenters believed that people who are open and expressive should, in general, make better first impressions than people who are reserved and relatively quiet.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers recruited college students and put them into pairs. The members of each pair had a 7-minute “getting acquainted” telephone conversation. The members of the pairs did not know each other and, in fact, they never saw each other. The participants also completed several personality measures, including the BLIRT scale. Note that they were NOT paired based on their BLIRT scores, so there were different combinations of blirtatiousness across the 32 pairs tested.

Try It

Query

Measuring Personality

You now know more about creating a personality test than most people do. Scales like the BLIRT or the Big Five test you took at the beginning of this exercise are used for serious purposes. Psychological researchers use them in their studies, of course. But psychological tests are also used by companies in their hiring process, by therapists trying to understand their patients, school systems assessing strengths and weaknesses of their students, and even sports teams trying to identify the best athletes to fit their system.

Blirtatiousness is simply an example of a personality trait, and it is not among the most widely used scales. There are hundreds of personality tests in use today. For example, the Big Five personality traits (conscientiousness, agreeability, neuroticism, openness to experience, and extraversion) are among the most widely used scales, and they have been extensively studied and validated. Other qualities, like intelligence, self-esteem, and general anxiety level, have also been widely studied, and they have well validated measures.

We hope that this exercise has given you some insight into the characteristics of a good personality test, and the work that goes into developing a useful scale. Next time you take one, consider the process that went into its development.

Glossary

convergent validity: the relationship between traits that are similar to (but not identical to) the trait being measured

criterion validity: the relationship between some measure and some real-world outcome

discriminant validity: the relationship between some traits that should have weak or no relationship

predictive validity: the relationship between experimental results and the ability to predict people’s behavior in certain situations

Footnotes

- The man who created the scale pronounced his name as LICK-ert. Many psychologists—maybe even your instructor—pronounce it LIKE-ert. It probably doesn’t matter much which way you say the name. ↵

- Note: Notice that the four items from the BLIRT are about what you DO. They aren’t about your beliefs (option 1), how you think other people see you (option 3), opinions about yourself (option 4), or what you think about other people (option 6). ↵

- Reverse scoring is simple: 7 becomes 1, 6 becomes 2, 5 becomes 3, 4 stays 4, 3 becomes 5, 2 becomes 6, and 1 becomes 7. Only the 4 items with the reverse wording are rescored this way. The goal is to make it so that higher numbers mean more blirtatious for all the items. ↵

- Cronbach’s alpha and Factor Analysis ↵

- The Rathus Assertiveness Schedule ↵

- Others included self-perceived social confidence, extraversion, impulsivity, and self-liking. ↵

- Other traits assessed for discriminant validity were agreeableness, conscientiousness, affect intensity (how strongly people were influenced by their emotions). ↵

Contributors and Attributions

CC licensed content, Original

- Psychology in Real Life: Blirtatiousness, Questionnaires, and Validity. Authored by: Patrick Carroll for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Sample of narcissistic personality disorder. Authored by: Raskin, R.; Terry, H. Provided by: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Located at: https://openpsychometrics.org/tests/NPI/. Project: A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. License: All Rights Reserved

- Sample of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem inventory. Authored by: Morris Rosenberg. Located at: https://openpsychometrics.org/tests/RSE.php. Project: Society and the adolescent self-image. License: All Rights Reserved