6.12: Globalization and Technology

- Page ID

- 60124

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Outcomes

- Explain the advantages and concerns of media globalization

- Describe the globalization of technology

In this section, we will look more closely at how media globalization and technological globalization are integral parts of culture and cultural diffusion. As the names suggest, media globalization is the worldwide integration of media (all print, digital, and electronic means of communication) through the cross-cultural exchange of ideas. Technological globalization refers to the cross-cultural development and exchange of technology. The speed with which culture is diffused has changed as a result of technological advances. Sharing of ideas, information, goods, and services through globalization is also possible because of advances in communication technology and the media.

Media Globalization

Have you ever traveled to another country and been surprised to see American advertisements or watched American television or movies abroad? How have companies like Disney successfully marketed their products around the world? Lyons (2005) suggests that multinational corporations are the primary vehicle of media globalization, and these corporations control global mass media content and distribution (Compaine 2005). It is true, when looking at who controls which media outlets, that there are fewer independent news sources as larger and larger conglomerates develop. The United States offers about 1,500 newspapers, 2,600 book publishers, and an equal number of television stations, plus 6,000 magazines and a whopping 10,000 radio outlets (Bagdikian 2004).

On the surface, there is endless opportunity to find diverse media outlets, but the numbers are misleading. Media consolidation is a process in which fewer and fewer owners control the majority of media outlets. In 1983, a mere 50 corporations owned the bulk of mass-media outlets. Today in the United States (which has no government-owned media) just five companies control 90 percent of media outlets (McChesney 1999). Ranked by 2014 company revenue, Comcast is the biggest, followed by the Disney Corporation, Time Warner, CBS, and Viacom (Time.com 2014).

Media consolidation results in the following dysfunctions:

- consolidated media owes more to its stockholders than to the public and represent the political and social interests of only a small minority

- there are fewer incentives to innovate, improve services, or decrease prices

- cultural and ideological bias can be widespread and based on the interests of who owns the purveyors of media

Although we have cases where social media was used to document the Arab Spring uprisings in real time in 2011, current research suggests that the public sphere accessing the global village will tend to be rich, Caucasoid, and English-speaking (Jan 2009) and not the predicted “global village” (McLuhan 1964).

Cultural and ideological bias are not the only risks of media globalization. In addition to the risk of cultural imperialism and the loss of local culture, other problems come with the benefits of a more interconnected globe. One risk is the potential for censoring by national governments that let in only the information and media they feel serve their message, as is occurring in China. Criminals can circumvent local laws against socially deviant and dangerous behaviors such as gambling, child pornography, and the sex trade. Offshore or international web sites allow U.S. citizens (and others) to seek out whatever illegal or illicit information they want, from twenty-four hour online gambling sites that do not require proof of age, to sites that sell child pornography. These examples illustrate the societal risks of unfettered information flow.

Watch It: Media and Culture

Listen to Dr. Tom Patterson, Bradlee Professor of Government and Press at Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy. He also serves as the Research Director of journalistsresource.org. In this clip, he talks a little bit about the Journalist Resource website as well as some of the consequences of globalization.

You can visit the website Journalist’s Resource. to learn about some topics related to culture in the news (click on “Society” and then “Culture” from the dropdown menu).

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: http://pb.libretexts.org/its/?p=136

Technological Globalization

Technological globalization is accelerated in large part by technological diffusion, or the spread of technology across borders. In the last two decades, there has been rapid improvement in the spread of technology to peripheral and semi-peripheral nations, and a 2008 World Bank report discussed both the benefits and ongoing challenges of this diffusion. In general, the report found that technological progress and economic growth rates were linked, and that the rise in technological progress helped improve the situations of many living in absolute poverty (World Bank 2008). The report recognized that rural and low-tech products such as corn can benefit from new technological innovations, and that, conversely, technologies like mobile banking can aid those whose rural existence consists of low-tech market vending. In addition, technological advances in areas like mobile phones can lead to competition, lowered prices, and concurrent improvements in related areas such as mobile banking and information sharing.

However, the same patterns of social inequality that create a digital divide, or the uneven access to technology among different races, classes, and geographic areas, in the United States also create digital divides within other nations. While the growth of technology use among countries has increased dramatically over the past several decades, the spread of technology within countries is significantly slower for certain nations. In these countries, far fewer people have the training and skills to take advantage of new technology, let alone access it. Technological access tends to be clustered around urban areas and leaves out vast swaths of citizens. While the diffusion of information technologies has the potential to resolve many global social problems, it is often the population most in need that is most affected by the digital divide. For example, technology to purify water could save many lives, but the villages most in need of water purification don’t have access to the technology, the funds to purchase it, or the technological comfort level to introduce it as a solution.

The Mighty Cell Phone: How Mobile Phones Are Impacting Sub-Saharan Africa

Many of Africa’s poorest countries suffer from a marked lack of infrastructure including poor roads, limited electricity, and minimal access to education and telephones. But while landline use has not changed appreciably during the past ten years, there’s been a fivefold increase in mobile phone access. More than a third of people in Sub-Saharan Africa have the ability to access a mobile phone (Katine 2010). Even more can use a “village phone”—through a shared-phone program created by the Grameen Foundation. With access to mobile phone technology, a host of benefits become available that have the potential to change the dynamics in these poorest nations. Sometimes that change is as simple as being able to make a phone call to neighboring market towns. By finding out which markets have vendors interested in their goods, fishers and farmers can ensure they travel to the market that will serve them best and avoid a wasted trip. Others can use mobile phones and some of the emerging money-sending systems to securely transfer money to a family member or business partner elsewhere (Katine 2010). Cell phone usage in Africa has increased rapidly in African nations, with two-fifths of sub-saharan Africans owning cell phones in 2016, and nine out of ten people owning cell phones in South Africa, Nigeria, and Ghana.[1] In fact, cell phone access has outpaced access to electricity in several central African nations.[2]

These shared-phone programs are often funded by businesses like Germany’s Vodafone or Britain’s Masbabi, which hope to gain market share in the region. Phone giant Nokia points out that there are 4 billion mobile phone users worldwide—that’s more than twice as many people as have bank accounts—meaning there is an opportunity to connect banking companies with people who need their services (ITU Telecom 2009). Not all access is corporate-based, however. Other programs are funded by business organizations that seek to help peripheral nations with tools for innovation and entrepreneurship.

But this wave of innovation and potential business comes with costs. There is, certainly, the risk of cultural imperialism, and the assumption that core nations (and core-nation multinationals) know what is best for those struggling in the world’s poorest communities. Whether well intentioned or not, the vision of a continent of Africans successfully chatting on their iPhone may not be ideal. Like all aspects of global inequity, access to technology in Africa requires more than just foreign investment. There must be a concerted effort to ensure the benefits of technology get to where they are needed most.

Technological Inequality

As with any improvement to human society, not everyone has equal access. Technology, in particular, often creates changes that lead to ever greater inequalities. In short, the gap gets wider faster. This technological stratification has led to a new focus on ensuring better access for all.

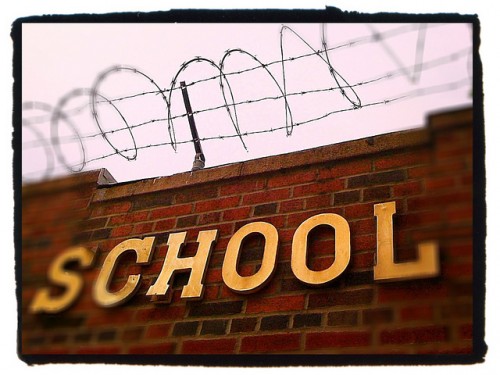

There are two forms of technological stratification. The first is differential class-based access to technology in the form of the digital divide. This digital divide has led to the second form, a knowledge gap, which is, as it sounds, an ongoing and increasing gap in information for those who have less access to technology. Simply put, students in well-funded schools receive more exposure to technology than students in poorly funded schools. Those students with more exposure gain more proficiency, which makes them far more marketable in an increasingly technology-based job market and leaves our society divided into those with technological knowledge and those without. Even as we improve access, we have failed to address an increasingly evident gap in e-readiness—the ability to sort through, interpret, and process knowledge (Sciadas 2003).

Since the beginning of the millennium, social science researchers have tried to bring attention to the digital divide. The term became part of the common lexicon in 1996, when then Vice President Al Gore used it in a speech. This was the point when personal computer use shifted dramatically, from 300,000 users in 1991 to more than 10 million users by 1996 (Rappaport 2009). In part, the issue of the digital divide had to do with communities that received infrastructure upgrades that enabled high-speed Internet access, upgrades that largely went to affluent urban and suburban areas, leaving out large swaths of the country.

At the end of the twentieth century, technology access was also a big part of the school experience for those whose communities could afford it. Early in the millennium, poorer communities had little or no technology access, while well-off families had personal computers at home and wired classrooms in their schools. In the 2000s, however, the prices for low-end computers dropped considerably, and it appeared the digital divide was ending. Research demonstrates that technology use and Internet access still vary a great deal by race, class, and age in the United States, though most studies agree that there is minimal difference in Internet use by adult men and adult women.

Data from the Pew Research Center (2011) suggest the emergence of yet another divide. As technological devices get smaller and more mobile, larger percentages of minority groups (such as Latinos and African Americans) are using their phones to connect to the Internet. In fact, about 50 percent of people in these minority groups connect to the web via such devices, whereas only one-third of whites do (Washington 2011). And while it might seem that the Internet is the Internet, regardless of how you get there, there’s a notable difference. Tasks like updating a résumé or filling out a job application are much harder on a cell phone than on a wired computer in the home. As a result, the digital divide might mean no access to computers or the Internet, but could mean access to the kind of online technology that allows for empowerment, not just entertainment (Washington 2011).

Mossberger, Tolbert, and Gilbert (2006) demonstrated that the majority of the digital divide for African Americans could be explained by demographic and community-level characteristics, such as socioeconomic status and geographic location. For the Latino population, ethnicity alone, regardless of economics or geography, seemed to limit technology use. Liff and Shepard (2004) found that women, who are accessing technology shaped primarily by male users, feel less confident in their Internet skills and have less Internet access at both work and home. Finally, Guillen and Suarez (2005) found that the global digital divide resulted from both the economic and sociopolitical characteristics of countries.

Technology Today

Does all this technology have a positive or negative impact on your life? When it comes to cell phones, a large majority of users check their phones for messages or calls even when the phone is not ringing. In addition, 71% of cell phone users sleep with the phone next to the bed, 60% of U.S. college students consider themselves to have a cell phone addiction, and 44% of people say they could not go a day without their cell phone.[3]

With so many people using social media both in the United States and abroad, it is no surprise that it is a powerful force for social change. Eighty-eight of 18- to 29-year-olds indicate that they use some form of social media.[4] You will read more about the influence of technology on social movements in later modules, but you can surely see examples around you of ways the technology has been used to raise awareness (like Twitter hashtags), fight stereotypes, or even change laws. In Latvia, two twenty-three-year-olds used a U.S. State Department grant to create an e-petition platform so citizens could submit ideas directly to the Latvian government. If at least 20 percent of the Latvian population (roughly 407,200 people) supports a petition, the government will look at it (Kumar 2014).

Think It Over

- Where do you get your news? Is it owned by a large conglomerate (you can do a web search and find out!)? Does it matter to you who owns your local news outlets? Why, or why not?

- To what extent is technology becoming a cultural universal?

- Can you think of people in your own life who support or defy the premise that access to technology leads to greater opportunities? How have you noticed technology use and opportunity to be linked, or does your experience contradict this idea?

glossary

- digital divide:

- the uneven access to technology around race, class, and geographic lines

- e-readiness:

- the ability to sort through, interpret, and process digital knowledge

- knowledge gap:

- the gap in information that builds as groups grow up without access to technology

- media:

- all print, digital, and electronic means of communication

- media consolidation:

- a process by which fewer and fewer owners control the majority of media outlets

- media globalization:

- the worldwide integration of media through the cross-cultural exchange of ideas

- technological diffusion:

- the spread of technology across borders

- technological globalization:

- the cross-cultural development and exchange of technology

- Cell Phones in Africa: Communication Lifeline. (2016, August 10). Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2015/04/15/cell-phones-in-africa-communication-lifeline/↵

-

https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2017/11/08/in-much-of-sub-saharan-africa-mobile-phones-are-more-common-than-access-to-electricity

↵

- Cell Phone Addiction. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.psychguides.com/behavioral-disorders/cell-phone-addiction/↵

- Smith, A., Anderson, M., Smith, A., & Anderson, M. (2018, September 19). Social Media Use 2018: Demographics and Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/↵

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Sarah Hoiland for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Introduction to Sociology 2e. Authored by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d/Introduction_to_Sociology_2e. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c...9333f3e1d@3.49

- The Internet, Globalization and the Media Future. Provided by: Harvard Kennedy School. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XuzvmoMCygg. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License