12.7: Sexual Orientation

- Page ID

- 60218

Learning Outcomes

- Define sexual orientation and understand the role of homophobia and heterosexism in society

- Describe how sexual identities are part of the socialization process

Sexual Orientation

A person’s sexual orientation is his or her physical, mental, emotional, and sexual attraction to a particular sex (male or female). Sexual orientation is typically divided into at least four categories: heterosexuality, the attraction to individuals of the other sex; homosexuality, the attraction to individuals of the same sex; bisexuality, the attraction to individuals of either sex; and asexuality, no attraction to either sex. Heterosexuals and homosexuals may also be referred to informally as “straight” and “gay,” respectively.

According to current scientific understanding, individuals are usually aware of their sexual orientation between middle childhood and early adolescence (American Psychological Association 2008). They do not have to participate in sexual activity to be aware of these emotional, romantic, and physical attractions; people can be celibate and still recognize their sexual orientation. Homosexual women (also referred to as lesbians), homosexual men (also referred to as gays), and bisexuals of both genders may have very different experiences of discovering and accepting their sexual orientation. At the point of puberty, some may be able to announce their sexual orientations, while others may be unready or unwilling to make their homosexuality or bisexuality known since it goes against U.S. society’s historical norms (APA 2008).

People identifying as GLBTQ, sometimes also written as LBGT and LBGTQ, stands for “Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender” (and “Queer” or “Questioning” when the Q is added) were surveyed and were asked about their “coming out” experiences. The average age gay men said they had “first thoughts” that one might be gay was 10 years old, while the average gay man “knew for sure” at 15 years of age and “told someone” at age 18; whereas respondents identifying as lesbian had substantially higher averages with 13, 18, and 21 respectively.[1] This suggests that there is a gender difference in terms of self-identifying and of sharing one’s sexual orientation with others.

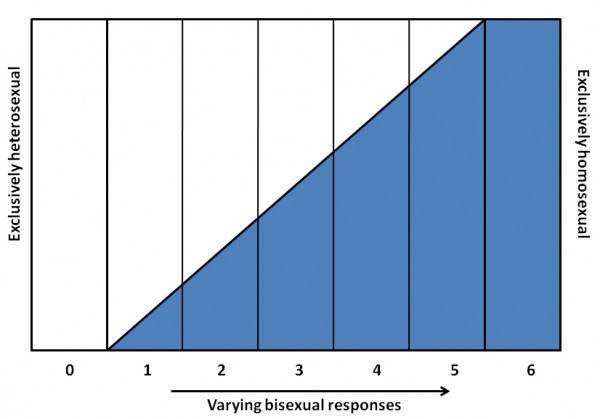

Alfred Kinsey was among the first to conceptualize sexuality as a continuum rather than a strict dichotomy of gay or straight. He created a six-point rating scale that ranges from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual. See the figure below. In his 1948 work Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Kinsey writes, “Males do not represent two discrete populations, heterosexual and homosexual. The world is not to be divided into sheep and goats … The living world is a continuum in each and every one of its aspects” (Kinsey 1948).

Later scholarship by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick expanded on Kinsey’s notions. She coined the term “homosocial” to oppose “homosexual,” and to describe nonsexual same-sex relations. Sedgwick recognized that in U.S. culture, males are subject to a clear divide between the two sides of this opposition, whereas females enjoy more fluidity. This can be illustrated by the way women in the United States can express homosocial feelings (nonsexual regard for people of the same sex) through hugging, handholding, and physical closeness. In contrast, U.S. males refrain from these expressions since they violate the heteronormative expectation that male sexual attraction should be exclusively for females. Research suggests that it is easier for women to violate these norms than men, because men are subject to more social disapproval for being physically close to other men (Sedgwick 1985). Sedgwick was also one of the founders of Queer Theory, which will be discussed later in this section.

There is no scientific consensus regarding the exact reasons why an individual holds a heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual orientation. Research has been conducted to study the possible genetic, hormonal, developmental, social, and cultural influences on sexual orientation, but there has been no evidence that links sexual orientation to one factor (APA 2008).

What is empirically clear is that GLBTQs are subjected to discrimination and violence in schools, the workplace, and the military. Much of this discrimination is based on stereotypes and misinformation. Some is based on heterosexism, which Herek (1990) suggests is both an ideology and a set of institutional practices that privilege heterosexuals and heterosexuality over other sexual orientations. Much like racism and sexism, heterosexism is a systematic disadvantage embedded in our social institutions, offering power to those who conform to hetereosexual orientation while simultaneously disadvantaging those who do not. Homophobia, an extreme or irrational aversion to homosexuals, accounts for further stereotyping and discrimination.

Major legal policies to prevent discrimination based on sexual orientation have only recently been instituted. In 2011, President Obama overturned “don’t ask, don’t tell,” a controversial policy that required homosexuals in the US military to keep their sexuality undisclosed. The Employee Non-Discrimination Act, which ensures workplace equality regardless of sexual orientation, is still pending full government approval. Organizations such as GLAAD (Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation) advocate for homosexual rights and encourage governments and citizens to recognize the presence of sexual discrimination and work to prevent it.

Sociologically, it is clear that gay and lesbian couples are negatively affected in states where they are denied the legal right to marriage. In 1996, The Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) was passed, explicitly limiting the definition of “marriage” to a union between one man and one woman. It also allowed individual states to choose whether or not they recognized same-sex marriages performed in other states. In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned part of DOMA in Windsor v. United States, and in 2015 same-sex marriage became legal nationwide when the Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges that state-level bans on same-sex marriage were unconstitutional. The court’s rationale was that the denial of marriage licenses to same-sex couples, and the refusal to recognize marriages performed in other jurisdictions, violated the Due Process and Equal Protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution.

Watch It: The 50th Anniversary of The Stonewall Riots

Watch this brief clip that summarizes what occurred at The Stonewall Inn, located in Greenwich Village in New York City, in 1969 and what is considered the origin of the Gay Liberation Movement.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: http://pb.libretexts.org/its/?p=334

Socialization and Sexual Identity

Like gender role socialization, sexual identities are heavily socialized from early ages. The United States is a heteronormative society, meaning it assumes sexual orientation is biologically determined and unambiguous. Consider that homosexuals are often asked, “When did you know you were gay?” but heterosexuals are rarely asked, “When did you know that you were straight?” (Ryle 2011).

Societal acceptance of homosexuality has increased over time, including in the U.S., where 60% of respondents in 2013 said homosexuality should be accepted, as opposed to 49% who said so in 2007. This still ranks well below Canada, Spain, Germany, the Czech Republic, France, Italy, Britain and Argentina, where national acceptance is over 70%[2] A Pew Research poll found that 63% of Americans said homosexuality should be accepted by society in 2016 [3]

A 2017 Gallup poll concluded that 4.5% of adult Americans identified as LGBT with 5.1% of women identifying as LGBT, compared with 3.9% of men. A different survey in 2016, from the Williams Institute, estimated that 0.6% of U.S. adults identify as transgender. Studies from several nations, including the U.S., conducted at varying time periods, have produced a statistical range of 1.2 to 6.8 percent of the adult population identifying as LGBT.

The District of Columbia has the highest GLBTQ population at 8.6%, followed by Vermont with 5.3%, Massachusetts, California, and Oregon, all at 4.9%, and Nevada with 4.8%.[4]

Like other aspects of socialization, norms and values related to sexuality and sexual orientation are transmitted through various agents of socialization beginning with the family. We can examine views on sexual orientation and examine other variables such as religion, country of origin, age, political affiliation, and others in order to theorize how values and norms related to sexual orientation operate.

Heteronormative behaviors are reinforced through agents of socialization, including popular movies and TV shows that feature LBGTQ relationships and individuals, which is symbolic of growing cultural awareness of relationships that are not heteronormative. Emmy-award winning comedienne Ellen DeGeneres broke early barriers by starring in a sitcom (Ellen 1994-1998) with herself as a gay female lead who comes out during an episode (April 30, 1997). Roseanne (1988-1997), starring Roseanne Barr, also revolutionarily featured several same sex couples and featured the first gay wedding of a recurring character in the episode “December Bride” (December 12, 1995). Roseanne made a comeback in 2018, but Barr herself was written out of the show and widely ostracized after posting an Islamophobic and racist tweet comparing an African American political operative to an ape.

The Showtime series Shameless (2011-present) has featured several same sex couples, and has intersected class, the military, and religion in its depiction of homosexual central character Ian Gallagher. HBO series Game of Thrones (2011-present) boasts 11 LGBTQ characters, including lesbian Lara Greyjoy and non-gender conforming Brienne of Tarth, among others.

Perhaps the biggest shift in popular culture has been to include LGBTQ characters in childrens’ series. The Legend of Korra (2012-2014), successor to Avatar: The Last Airbender (2005-2008), features a queer lead and explicitly addresses sexism. [5]

In 2012, Tammy Baldwin became the first openly gay politician, and the first Wisconsin woman, to be elected to the U.S. Senate. Prior to being elected to the Senate, Baldwin had been the first openly gay member of the U.S. Congress, joining the body in 1998.

glossary

[glossary-page]

[glossary-term]heteronormative society:[/glossary-term]

[glossary-definition]assumes sexual orientation is biologically determined and unambiguous[/glossary-definition]

[glossary-term]heterosexism:[/glossary-term]

[glossary-definition]an ideology and a set of institutional practices that privilege heterosexuals and heterosexuality over other sexual orientations[/glossary-definition]

[glossary-term]sexual orientation:[/glossary-term]

[glossary-definition]a person’s physical, mental, emotional, and sexual attraction to a particular sex (male or female)[/glossary-definition]

[/glossary-page]

- "A survey of LBGT Americans." (2013). Pew Research Center. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/06/13/a-survey-of-lgbt-americans/. ↵

- "The global divide on homosexuality," 2013. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2013/06/04/the-global-divide-on-homosexuality/. ↵

- Brown. A. 2017. "Five key findings." Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/06/13/5-key-findings-about-lgbt-americans/. ↵

- Gates, G. 2017. "Vermont leads states LGBT identification," Gallop Social and Public Issues. https://news.gallup.com/poll/203513/vermont-leads-states-lgbt-identification.aspx. ↵

- Necessary, T. "10 Kids Shows." Pride. https://www.pride.com/geek/2019/1/27/10-modern-kids-shows-awesome-queer-characters. ↵

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Sex and Gender; Sex and Sexuality. Authored by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: https://cnx.org/contents/AgQDEnLI@11.1:JvZuwiUn@7/Sex-and-Gender. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c...9333f3e1d@3.49

- Stonewall Inn. Authored by: Rhododendrites . Provided by: Wikpedia. Located at: https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Stonewall_Inn#/media/File:Stonewall_Inn_10_pride_weekend_2016.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- LGBT demographics of the United States. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/LGBT_demographics_of_the_United_States. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- How the Stonewall Riots Sparked a Movement. Provided by: History. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=181&v=Q9wdMJmuBlA. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License