21.7: Theoretical Perspectives on Social Movements

- Page ID

- 60343

Learning Objectives.

- Discuss theoretical perspectives on social movements, like resource mobilization, framing, and new social movement theory

Theoretical Perspectives on Social Movements

Most theories of social movements are called collective action theories, indicating the purposeful nature of this form of collective behavior. The following three theories are but a few of the many classic and modern theories developed by social scientists.

Resource Mobilization

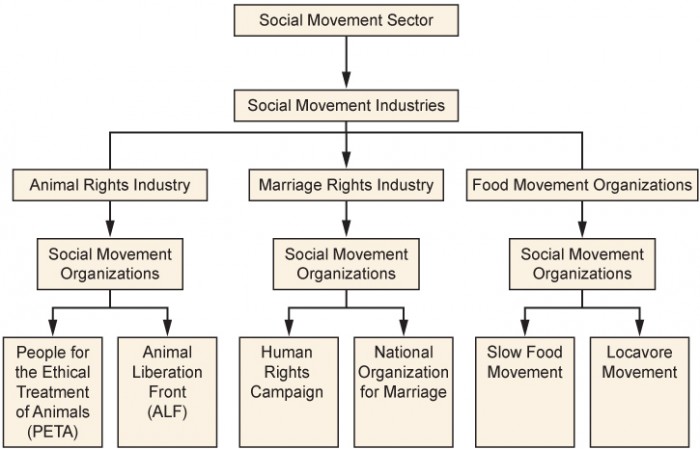

McCarthy and Zald (1977) conceptualize resource mobilization theory as a way to explain movement success in terms of the ability to acquire resources and mobilize individuals. Resources are primarily time and money, and the more of both, the greater the power of organized movements. Numbers of social movement organizations (SMOs), which are single social movement groups, with the same goals constitute a social movement industry (SMI). Together they create what McCarthy and Zald (1977) refer to as “the sum of all social movements in a society.”

Resource Mobilization and the Civil Rights Movement

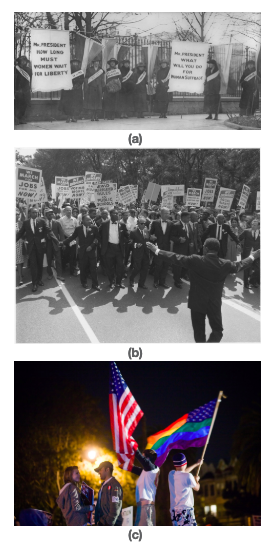

An example of resource mobilization theory is activity of the civil rights movement in the decade between the mid 1950s and the mid 1960s. Social movements had existed before, notably the Women’s Suffrage Movement and a long line of labor movements, thus constituting an existing social movement sector, which is the multiple social movement industries in a society, even if they have widely varying constituents and goals. The civil rights movement had also existed well before Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat to a white man. Less known is that Parks was a member of the NAACP and trained in leadership (A&E Television Networks, LLC. 2014). But her action that day was spontaneous and unplanned (Schmitz 2014). Her arrest triggered a public outcry that led to the famous Montgomery bus boycott, turning the movement into what we now think of as the “civil rights movement” (Schmitz 2014).

Mobilization had to begin immediately. Boycotting the bus made other means of transportation necessary, which was provided through car pools. Churches and their ministers joined the struggle, and the protest organization In Friendship was formed as well as The Friendly Club and the Club From Nowhere. A social movement industry, which is the collection of the social movement organizations that are striving toward similar goals, was growing.

Martin Luther King Jr. emerged during these events to become the charismatic leader of the movement, gained respect from elites in the federal government, and aided by even more emerging SMOs such as the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), among others. Several still exist today. Although the movement in that period was an overall success, and laws were changed (even if not attitudes), the “movement” continues. So do struggles to keep the gains that were made, even as the U.S. Supreme Court has recently weakened the Voter Rights Act of 1965, once again making it more difficult for black Americans and other minorities to vote.

Watch It

This video provides an explanation of how theories on social movements have evolved over time. For example, you’ll learn about mass society theory, relative deprivation theory, resource mobilization theory, and rational choice theory. Consider which of these theories best explains the emergence of a social movement you’ve learned about in this module.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: http://pb.libretexts.org/its/?p=602

Framing/Frame Analysis

Over the past several decades, sociologists have developed the concept of frames to explain how individuals identify and understand social events and which norms they should follow in any given situation (Goffman 1974; Snow et al. 1986; Benford and Snow 2000). Imagine entering a restaurant. Your “frame” immediately provides you with a behavior template. It probably does not occur to you to wear pajamas to a fine-dining establishment, throw food at other patrons, or spit your drink onto the table. However, eating food at a sleepover pizza party provides you with an entirely different behavior template. It might be perfectly acceptable to eat in your pajamas and maybe even throw popcorn at others or guzzle drinks from cans.

Successful social movements use three kinds of frames (Snow and Benford 1988) to further their goals. The first type, diagnostic framing, states the problem in a clear, easily understood way. When applying diagnostic frames, there are no shades of gray: instead, there is the belief that what “they” do is wrong and this is how “we” will fix it. The anti-gay marriage movement is an example of diagnostic framing with its uncompromising insistence that marriage is only between a man and a woman. Prognostic framing, the second type, offers a solution and states how it will be implemented. Some examples of this frame, when looking at the issue of marriage equality as framed by the anti-gay marriage movement, include the plan to restrict marriage to “one man/one woman” or to allow only “civil unions” instead of marriages. As you can see, there may be many competing prognostic frames even within social movements adhering to similar diagnostic frames. Finally, motivational framing is the call to action: what should you do once you agree with the diagnostic frame and believe in the prognostic frame? These frames are action-oriented. In the gay marriage movement, a call to action might encourage you to vote “no” on Proposition 8 in California (a move to limit marriage to male-female couples), or conversely, to contact your local congressperson to express your viewpoint that marriage should be restricted to male-female couples.

With so many similar diagnostic frames, some groups find it best to join together to maximize their impact. When social movements link their goals to the goals of other social movements and merge into a single group, a frame alignment process (Snow et al. 1986) occurs—an ongoing and intentional means of recruiting participants to the movement.

This frame alignment process has four aspects: bridging, amplification, extension, and transformation. Bridging describes a “bridge” that connects uninvolved individuals and unorganized or ineffective groups with social movements that, though structurally unconnected, nonetheless share similar interests or goals. These organizations join together to create a new, stronger social movement organization. Can you think of examples of different organizations with a similar goal that have banded together?

In the amplification model, organizations seek to expand their core ideas to gain a wider, more universal appeal. By expanding their ideas to include a broader range, they can mobilize more people for their cause. For example, the Slow Food movement extends its arguments in support of local food to encompass reduced energy consumption, pollution, obesity from eating more healthfully, and more.

In extension, social movements agree to mutually promote each other, even when the two social movement organization’s goals don’t necessarily relate to each other’s immediate goals. This often occurs when organizations are sympathetic to each others’ causes, even if they are not directly aligned, such as women’s equal rights and the civil rights movement.

Transformation means a complete revision of goals. Once a movement has succeeded, it risks losing relevance. If it wants to remain active, the movement has to change with the transformation or risk becoming obsolete. For instance, when the women’s suffrage movement gained women the right to vote, members turned their attention to advocating equal rights and campaigning to elect women to office. In short, transformation is an evolution in the existing diagnostic or prognostic frames that generally achieves a total conversion of the movement.

New Social Movement Theory

New social movement theory, a term developed by European social scientists in the 1950s and 1960s, attempts to explain the proliferation of postindustrial and postmodern movements that are difficult to analyze using traditional social movement theories. Rather than being one specific theory, it is more of a perspective that revolves around understanding movements as they relate to politics, identity, culture, and social change. The primary difference is in their goals, as the new movements focus not on issues of materialistic qualities such as economic wellbeing, but on issues related to human rights (such as gay rights or pacifism).

Some of these more complex interrelated movements include ecofeminism, which focuses on the patriarchal society as the source of environmental problems, and the transgender rights movement. Sociologist Steven Buechler (2000) suggests that we should be looking at the bigger picture in which these movements arise—shifting to a macro-level, global analysis of social movements.

The Movement to Legalize Marijuana

The movement to legalize marijuana can be an example of a New Social Movement theory as it focuses on changing the culture of the United States by assimilating a previous illegal substance into something people could legalize use in their everyday life thus creating a new norm for what is considered deviant in society. The early history of marijuana in the United States includes its use as an over-the-counter medicine as well as various industrial applications. Its recreational use eventually became a focus of regulatory concern. Public opinion, swayed by a powerful propaganda campaign by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics in the 1930s, remained firmly opposed to the use of marijuana for decades. In the 1936 church-financed propaganda film “Reefer Madness,” marijuana was portrayed as a dangerous drug that caused insanity and violent behavior.

One reason for the recent shift in public attitudes about marijuana, and the social movement pushing for its decriminalization, is a more-informed understanding of its effects that largely contradict its earlier characterization. The public has also become aware that penalties for possession have been significantly disproportionate along racial lines. U.S. Census and FBI data reveal that blacks in the United States are between two to eight times more likely than whites to be arrested for possession of marijuana (Urbina 2013; Matthews 2013). Further, the resulting incarceration costs and prison overcrowding are causing states to look closely at decriminalization and legalization.

In 2012, marijuana was legalized for recreational purposes in Washington and Colorado through ballot initiatives approved by voters. While it remains a Schedule One controlled substance under federal law, the federal government has indicated that it will not intervene in state decisions to ease marijuana laws. Cannabis is now legal for recreational use in over 10 states, legal for medical use for other 33, and decriminalized in many others.[1]

Watch IT

Watch this Ted talk by Greg Satell to learn more about the things that make a successful social movement.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: http://pb.libretexts.org/its/?p=602

Think It Over

- Think about a social movement industry dealing with a cause that is important to you. How do the different social movement organizations of this industry seek to engage you? Which techniques do you respond to? Why?

- Do you think social media is an important tool in creating social change? Why, or why not? Defend your opinion.

- Describe a social movement in the decline stage. What is its issue? Why has it reached this stage?

- diagnostic framing:

- a the social problem that is stated in a clear, easily understood manner

- frame alignment process:

- using bridging, amplification, extension, and transformation as an ongoing and intentional means of recruiting participants to a movement

- motivational framing:

- a call to action

- new social movement theory:

- a theory that attempts to explain the proliferation of postindustrial and postmodern movements that are difficult to understand using traditional social movement theories

- prognostic framing:

- social movements that state a clear solution and a means of implementation

- resource mobilization theory:

- a theory that explains social movements’ success in terms of their ability to acquire resources and mobilize individuals

- social movement industry:

- the collection of the social movement organizations that are striving toward similar goals

- social movement organization:

- a single social movement group

- social movement sector:

- the multiple social movement industries in a society, even if they have widely varying constituents and goals

- Berke, Jeremy and Skye Gould (March 2016). New Jersey lawmakers postponed a critical vote to legalize marijuana — here are all the states where pot is legal. Business Insider. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/legal-marijuana-states-2018-1↵

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Rebecca Vonderhaar for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Social Movements. Authored by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: https://cnx.org/contents/AgQDEnLI@10.1:zqE5zZje@5/Social-Movements. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c...9333f3e1d@10.1.

- Explanatory sentence on goals of new social movements. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/New_social_movements. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Social movements | Society and Culture | MCAT . Provided by: Khan Academy. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y7YPTD7QwR4. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Why do some movements succeed, while others fail?. Authored by: Greg Satell. Provided by: TEDx. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IOt1dLVyHjQ. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License