7.3: Intersectionality

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 104071

- Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, & Joy Tsuhako

- Long Beach City College, Cerritos College, & Saddleback College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Origins of Intersectionality

This body of work, not to mention other contributions by Black feminists such as Patricia Hill Collins, Kimberlé Crenshaw, bell hooks, Audre Lorde, Barbara Smith, and others, engages in critical and important conversations about Black sexuality. Black feminists, for example, provided a theoretical lens to examine oppression referred to as intersectionality. This tool continues to be a major contribution as it examines how individuals experience oppression differently based on their social location in terms of their sexuality, gender, class, race, ability, and religion, among other identities.

Sociologist Patricia Hill Collins (1990) developed the matrix of domination/oppression, a sociological paradigm that explains issues of oppression that deal with race, class, and gender. Other forms of classification such as sexual orientation, religion, or age apply to this theory as well. In Collins’ Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, she first describes the concept of matrix thinking within the context of how Black women in America encounter institutional discrimination based upon their race and gender. A prominent example of this in the 1990s was racial segregation, especially as it related to housing, education, and employment. At the time, there was very little encouraged interaction between whites and Blacks in these common sectors of society. Collins argues that this demonstrates how being Black and female in America continues to perpetuate certain common experiences for African-American women. As such, African-American women live in a different world than those who are not Black and female. Collins notes how this shared social struggle can actually result in the formation of a group-based collective effort, citing how the high concentration of African-American women in the domestic labor sector in combination with racial segregation in housing and schooling contributed directly to the organization of the Black feminist movement. The collective wisdom shared by Black women that held these specific experiences constituted a distinct viewpoint for African-American women concerning correlations between their race and gender and the resulting economic consequences.

Kimberlé Crenshaw, the founder of the term intersectionality, brought national and scholarly credential to the term through the paper Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics in The University of Chicago Legal Forum. In the paper, she uses intersectionality to reveal how feminist movements and anti-racist movements exclude women of color. Focusing on the experiences of Black women, she dissects several court cases, influential pieces of literature, personal experiences, and doctrinal manifestations as evidence for the way Black women are oppressed through many different experiences, systems, and groups.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=328&height=492)

Though the specifics differ, the basic argument is the same: Black women are oppressed in a multitude of situations because people are unable to see how their identities intersect and influence each other. Feminism has been crafted for white middle-class women, hence only considering problems that affect this group of people. Unfortunately, this only captures a small facet of the oppression women face. By catering to the most privileged women and addressing only the problems they face, feminism alienates women of color and lower-class women by refusing to accept the way other forms of oppression feed into the sexism they face. Not only does feminism completely disregard the experiences of women of color, it also solidifies the connection between womanhood and whiteness when feminists speak for "all women" (Crenshaw, 1989, p. 154) Oppression cannot be detangled or separated easily in the same way identities cannot be separated easily. It is impossible to address the problem of sexism without addressing racism, as many women experience both racism and sexism. This theory can also be applied to the anti-racist movement, which rarely addresses the problem of sexism, even though it is thoroughly intertwined with the problem of racism. Feminism remains white, and antiracism remains male. In essence, any theory that tries to measure the extent and manner of oppression Black women face will be wholly incorrect without using intersectionality.

Both intersectionality and the matrix of domination help sociologists understand power relationships and systems of oppression in society. The matrix of domination looks at the overall organization of power in society while intersectionality is used to understand a specific social location of an identity using mutually constructing features of oppression. The concept of intersectionality today is used to move away from one dimensional thinking in the matrix of domination approach by allowing for different power dynamics of different identity categories at the same time. Researchers in public health are using Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis (IBPA) Framework to show how social categories intersect to identify health disparities that evolve from factors beyond an individual's personal health.

Intersectionality can also be used to correct for the over-attribution of traits to groups and be used to emphasize unique experiences within a group. As a result, the field of social work is introducing intersectional approaches in their research and client interactions. At the University of Arkansas, the curriculum for a Master of Social Work (MSW) is being amended to include the Multi-Systems Life Course (MSLC) approach. Christy and Valandra apply an MSLC approach to intimate partner violence and economic abuse against poor women of color to explain that symbols of safety (such as police) in one population can be symbols of oppression in another. By teaching this approach to future social workers, the default recommendation for these women to file a police report is amended and an intervention rooted in the individual case can emerge.

Black Sexuality and Origins of Discrimination

Black Sexuality and Origins of Discrimination

Twinet Parmer and James Gordon (2007) describe Black sexuality as “a collective cultural expression of the multiple identities as sexual beings of a group of Africans in America, who share a slave history that over time has strongly shaped the Black experiences in white America.” There has been a more pronounced focus on Black sexuality than on the sexuality of other ethnic groups. Sharon Rachel and Christian Thrasher (2015) note that “[t]here is no discourse on ‘white’ sexuality, ‘Jewish’ sexuality, ‘Native American’ sexuality, etc.” Even though there is not much work to speak of that focuses on “white” heterosexuality per se in the ways in which the discourse on Black sexuality has been created, it is safe to say that the dominant discourse about sexuality centers and normalizes white sexuality in general and is grounded in dominant cultural terms. It is also important to note that there has been pushback to de-center whiteness. Counternarratives, a component of Critical Race Theory as discussed in Chapter 2.3, question and interrogate the backdrop of whiteness (see also Chapter 6.3) that has been used to normalize white hegemonic sexuality on the one hand and at the same time degrade Black sexuality on the other hand. Black sexuality has historically been negatively judged against a particular kind of white sexual norms: “[t]he pathologizing of Black sexuality continued as means of affirming the superior status of Europeans while restricting the social movement of Black people by characterizing egalitarian interaction with them as undesirable”(McCruder, 2010, p. 104)

Perhaps one of the most poignant and foundational examples of debasing the female Black body with a particular emphasis on big breasts, buttocks, and other sexual body parts occurred in the early nineteenth century with the European obsession with a woman named Saartjie Baartman (1789-1815). Also known as “The Hottentot Venus,” Baartman was a Khoikhoi woman originally from southwest Africa. Essentially, Baartman was taken from her homeland in Africa to Europe, where she was put on exhibit for public viewings in England and France from 1810 until her death. Such a display of Baartman’s body was certainly a way of “Othering” her Black body, especially compared with white European women. Exhibiting Baartman was both a way of showing various aspects of Black sexuality as well as making her a spectacle. Her years on exhibition constituted more of an ongoing “freak show” than honoring Baartman or her body in any way. Magdalena Barrera (2002) has noted that “When the [public] paid to see her ‘perform’—she was held in a cage and made to dance half-naked in order to receive any food...People were so perplexed upon seeing her that they debated whether she was even human.” Following her death in 1815, Baartman’s image remained on display in the form of a plaster cast of her body at the Mus᷇ee de l’Homme in Paris, France, and her sexual body parts were preserved and kept on display until the 1970s. It was not until 2002 that Saartjie Baartman’s bodily remains were returned to her homeland in South Africa for a proper, respectful, and humane burial based on an arrangement made by South African President Nelson Mandela with the French government. Baartman's story illustrates the exoticization of the Black female body, which reified and perpetuated the Western notion of Blackness and linked it to being less than human, lascivious, and non-normative.

This section is licensed CC BY-NC. Attribution: Slavery to Liberation: The African American Experience (Encompass) (CC BY-NC 4.0)

Setting the Stage for Negative Attitudes About Black Sexuality

While the Baartman story provides a single example of the characterization of Black sexuality, it fits with a larger picture of the social construction of race, discussed in Chapter 1.2, that pre-dates Baartman being put on display in Europe. Europeans formed their views of Black people as far back as the sixteenth century. When Europeans came into contact with Africans and witnessed how they interacted sexually with other Africans and non-African individuals as well as the degree to which Africans were clothed, negative attitudes were formed about African sexuality. Historian Kevin McGruder (2010) further states that “[t]he limited apparel worn by most Africans was interpreted by Europeans as a sign of lasciviousness or lack of modesty rather than a concession to the tropical climate. Linked to this impression was a perception that the sex drives of Africans were uncontrollable.” Even more insidious was the suggestion that African people were less than human, even to the extent of their being animalized. This portrayal of African people by Europeans continued for the duration not only of chattel slavery in the American South from 1619 to 1863, but also long after slavery ended into the Jim Crow Era and beyond. Another factor that influenced and perpetuated racist ideologies that concerned both sexual and non-sexual aspects of Black people involved scientific racism that was prominent from the 1600s until the end of World War II (now regarded as pseudo-science or racialized science and thoroughly disregarded as nonsense). Among the academic and professional fields that practiced scientific racism were anthropology, biological sciences, medicine, and so on, in Europe and the United States. A description of Black people from this perspective was written by the nineteenth-century French naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier, the same individual who dissected and preserved Baartman’s sexual body parts, appeared in his book The Animal Kingdom: Arranged in Conformity with Its Organization. Among many other topics, Cuvier covered the varieties of the human species. In part, he wrote, “The Negro race is confined to the south of mount Atlas; it is marked by a Black complexion; crisp or woolly hair, compressed cranium, and a flat nose. The projection of the lower parts of the face, and the thick lips, evidently appropriate it to the monkey tribe; the hordes of which it consists have always remained in the most complete state of barbarism” (Cuvier, 1817). Such a description is not only generally dehumanizing but the likening of people of African descent to animals extends to attitudes about their sexuality. Such attitudes deriving from the observations of African people by Europeans when they first visited Africa in the sixteenth century coupled with the racist pseudo-science that was characterized by Cuvier’s claims above, in part, provided a rationale for enslaving people of African descent in North America, in particularly what would become the Southern states of the U.S.

Countering the Negativity About Black Sexuality

While it is important to mark the systemic racism (defined in Chapter 4.4) that has pointed to mainstream society’s discomfort and fear of Black sexuality, it is equally as important to discuss actions that have fought against such injustices. It is absolutely true that Black people and their communities have been maltreated by hundreds of years of racism that have caused both symbolic and material harm. The injustices done by castigating Black individuals for their sexuality have been unconscionable. Such abuses in the forms of microaggressions and macroaggressions have had significant detrimental impacts. There is no question about how profoundly Black individuals and their communities have suffered from racism and how that translated, in part, into demonizing their sexuality. That history is real and needs to be respected and in no way covered up or misrepresented. At the same time, it is also important to point out how Black people and their allies responded and fought back in response to the prejudice and discrimination regarding Black sexual matters.

In a number of ways, resistance to fight against racism has been both realized and effective. One such example is the NAACP’s response to Birth of a Nation (introduced earlier in Chapter 1.4). While it is true that many of the goals of the NAACP including censoring the film did not take hold, a number of other benefits for the NAACP and civil rights came as a result of organizing against the film. In the very early years of its existence, the NAACP focused predominantly on problematic issues that occurred almost exclusively in the South such as housing segregation and lynchings. However, once a Birth of a Nation was released, protests occurred all over the United States, as this film was a national phenomenon and relevant to more than one specific geographical area. Historian Stephen Weinberger (2011) put it best by asserting, “What is perhaps most interesting and important about the campaign against Birth is that while it did not achieve its goals, it transformed the NAACP in ways no one could have anticipated."

The Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s constituted many African American writers, artists, and social critics who questioned and challenged the pervasive stereotypes, racism, discrimination, and prejudice that haunted Black people from the slavery era well into the Jim Crow period in American history. Besides the overarching cultural work that the Harlem Renaissance achieved, it showed progress in the area of Black sexuality, as “we now know that many of the most significant participants within the Renaissance were... [gay, lesbian, bisexual, and queer people] who found unprecedented amounts of social and intellectual freedom in 1920s New York, not to mention places like Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Atlanta.” Such writers as Langston Hughes and Richard Bruce Nugent included queer themes in their writings, and Blues singer Gladys Bentley often performed in drag. Additionally, drag balls held during this period included hundreds of individuals who were cross-dressed. These are merely a few of the numerous individuals who contributed to this rich historical period. The cultural work that resulted certainly challenged the hegemonic narrative that long haunted Black Americans generally and more specifically about their sexuality.

Long before the successes of striking down the miscegenation laws nationally with the Supreme Court ruling on the Loving v. Virginia case (see also Chapter 1.4), fearless Black activists existed. A prime example of such courage in the face of savage and deadly racism were Black feminists. One such activist was Ida B. Wells (1862-1931), a journalist, “who not only exploded the myth of bestial, white-female-obsessed Black brute but who also established remarkably sophisticated ways of thinking of lynching as a means of controlling newly emancipated—and partially enfranchised—Black American populations.” A number of other Black activists spoke out against anti-Black sentiment connected to Black sexuality. Black icons W.E.B. Dubois (1868-1963), Mary Church Terrell (1863-1954), and Walter Francis white (1893-1955) were champions who specifically challenged the stereotype of the uncivilized Black male who sexually preyed on white women.

Another positive turn occurred when miscegenation laws nationwide were overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court. The last vestige of segregation laws was ruled unconstitutional in the famous court case of Loving v. Virginia in June of 1967. As a result of this Supreme Court ruling, all laws that banned marriages between individuals of mixed racial heritage were null and void. This finding freed individuals to marry whom they wished irrespective of the racial makeup of both people in the relationship. The case was a major victory considering the entrenched widespread belief and legal backing that white and Black individuals could not have interracial sex.

Issues of Black sexuality have surfaced in many other ways through popular culture. It has been a “mixed bag” in terms of perpetuating old, harmful stereotypes on the one hand or being liberatory on the other hand. Yet, some representations cannot be so neatly categorized in one camp or the other. Hollywood movies have portrayed Black sexuality in various ways, and music icons such as Aretha Franklin, Whitney Houston, Janet Jackson, Marvin Gaye, Prince, and others have lyrics in their songs that get at the heart of sex and relationships. How about rap and hip-hop artists and their messages about (Black) sexuality? How have they contributed to the discourse on Black sexuality? How about incidents that have spurred discussion such as when Magic Johnson was diagnosed with HIV, or the Congressional hearings that ensued when Clarence Thomas was being nominated to be an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court and Anita Hill brought charges of sexual harassment? How about popular television programs that feature African Americans? How about the notion of the “Down Low” that was originally discussed as an African American male phenomenon in which presumably otherwise straight men would have sexual contact with other men in a clandestine fashion? While space constraints do not allow for fuller details, descriptions, and analyses of these various popular cultural representations of Black sexuality, they are certainly worthy of detailed analysis in terms of how they have influenced our views and discourses about Black sexuality in U.S. society.

African-American LGBTQ Community

The African-American LGBTQ community is part of the overall LGBTQ culture. LGBTQ stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer. The LGBTQ community did not receive societal recognition until the historical marking of the Stonewall Riots in 1969 in New York at Stonewall Inn. The Stonewall riots brought domestic and global attention to the lesbian and gay community. During the first night of the Stonewall riots, LGBTQ African Americans and Latinos likely were the largest percentage of the protestors, because those groups heavily frequented the bar.

During the Harlem Renaissance, a subculture of LGBTQ African-American artists and entertainers emerged, including people like Alain Locke, Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, Wallace Thurman, Richard Bruce Nugent, Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, Moms Mabley, Mabel Hampton, Alberta Hunter, and Gladys Bentley. Places like Savoy Ballroom and the Rockland Palace hosted drag-ball extravaganzas with prizes awarded for the best costumes. Langston Hughes depicted the balls as "spectacles of color." George Chauncey, author of Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940, wrote that during this period "perhaps nowhere were more men willing to venture out in public in drag than in Harlem."

Black Lesbian Identity

There has historically been a lot of racism and racial segregation in lesbian spaces. Racial and class divisions sometimes made it difficult for Black and white women to see themselves as on the same side in the feminist movement. Black women faced misogyny from within the black community even during the fight for Black liberation. Homophobia was also pervasive in the black community during the Black Arts Movement because “feminine” homosexuality was seen as undermining Black power. Black lesbians especially struggled with the stigma they faced within their own community. With unique experiences and often very different struggles, Black lesbians have developed an identity that is more than the sum of its parts – Black, lesbian, and woman. Some individuals may rank their identities separately, seeing themselves as Black first, woman second, lesbian third, or some other permutation of the three; others see their identities as inextricably interwoven.

Black Transgender People

Black transgender individuals face higher rates of discrimination than black LGB individuals. While policies have been implemented to inhibit discrimination based on gender identity, transgender individuals of color lack legal support. Transgender individuals are still not supported by legislation and policies like the LGBTQ community. New reports show vast discrimination in the black transgender community. Reports show in the National Transgender Discrimination Survey that black transgender individuals, along with non-conforming individuals, have high rates of poverty. Statistics shows a 34% rate of households receiving an income less than $10,000 a year. According to the data, that is twice the rate when looking at transgender individuals of all races and four times higher than the general Black population. Many face poverty due to discrimination and bias when trying to purchase a home or apartment. Thirty-eight percent of black trans individuals report in the Discrimination Survey being turned down property due to their gender identity, while 31% of the Black individuals were evicted due to their identity.

Black transgender individuals also face disparities in education, employment, and health. In education, Black transgender and non-conforming persons face brutish environments while attending school. Reporting rates show 49% of black transgender individuals being harassed from kindergarten to twelfth grade. Physical assault rates are at 27% percent, and sexual assault is at 15%. These drastically high rates have an effect on the mental health of black transgender individuals. As a result of high assault/harassment and discrimination, suicide rates are at the same rate (49%) as harassment to Black transgender individuals. Employment discrimination rates are similarly higher. Statistics show a 26% rate of unemployed black transgender and non-conforming persons. Many Black trans people have lost their jobs or have been denied jobs due to gender identity: 32% are unemployed, and 48% were denied jobs.

Black Gay Pride Movement

The Black Gay Pride movement is a movement within the United States for African American members of the LGBTQ community. Started in the 1990s, Black Gay Pride movements began as a way to provide Black LGBTQ people an alternative to the largely white mainstream LGBTQ movement. White gay prides enforce, both consciously and unconsciously, the long history of ignoring the people of color who share in the experiences. The history of segregation seen in other organizations such as nursing associations, journalism associations, and fraternities is carried on into the black gay prides seen today. The exclusion of people of color in gay pride events plays into the existing undertones of white superiority and racist political movements. In response, the movement serves as a way for black LGBT people to discuss specific issues that are more unique to the black LGBT community and celebrate the progress of the black LGBTQ community. While the mainstream gay pride movement, often perceived as overwhelmingly white, has focused much of its energy on same-sex marriage, the Black Gay Pride movement has focused on issues such as racism, homophobia, and lack of proper health and mental care in Black communities.

Today, there are about 20 Black Gay Pride events all over the United States. The largest of these events have historically been D.C. Black Pride and Atlanta Black Pride. While black pride events started as early as 1988, D.C. Black Pride, which began in 1991, has been cited as one of the earliest celebrations. The D.C. Black Pride celebration started out of a tradition called the Children's Hour 15 years prior.

Economic Disparities within the African-American LGBTQ Community

Within the Black LGBTQ community many face economic disparities and discrimination. Statistically Black LGBTQ individuals are more likely to be unemployed than their non-Black counterparts. According to the Williams Institute, the vast difference lies in the survey responses of “not in workforce” from different populations geographically. Black LGBTQ individuals, nonetheless, face the dilemma of marginalization in the job market. As of 2013, same-sex couples' income is lower than those in heterosexual relationships with an average of $25,000 income. For opposite-sex couples, statistics show a $1,700 increase. Analyzing economic disparities on an intersectional level (gender and race), the Black man is likely to receive a higher income than a woman. For men, statistics shows approximately a $3,000 increase from the average income for all Black LGBTQ identified individuals, and a $6,000 increase in salary for same-sex male couples. Female same-sex couples receive $3,000 less than the average income for all Black LGBTQ individuals and approximately $6,000 less than their male counterparts. The income disparity amongst black LGBTQ families affects the lives of their dependents, contributing to poverty rates. Children growing up in low-income households are more likely to remain in the poverty cycle. Due to economic disparities in the black LGBTQ community, 32% of children raised by gay Black men are in poverty. However, only 13% of children raised by heterosexual Black parents are in poverty and only 7% for white heterosexual parents.

Comparatively looking at gender, race, and sexual orientation, Black women same-sex couples are likely to face more economic disparities than Black women in an opposite sex relationship. Black women in same-sex couples earn $42,000 compared to Black women in opposite-sex relationships who earn $51,000, a twenty-one percent increase in income. Economically, Black women same-sex couples are also less likely to be able to afford housing. Approximately fifty percent of black women same-sex couples can afford to buy housing compared to white women same-sex couples who have a seventy-two percent rate in home ownership.

Adultification Bias of Black Girls

Adultification bias is a form of racial prejudice where children of people of colors, such as African American girls, are treated as being more mature than they actually are by a reasonable social standard of development. As such, African American girls have reported to be treated unfairly such as their true ages were disbelieved when they told authority figures like police officers, and facing consequences in school for misbehaviors while white girls doing the same acts would have their young ages taken into account.

This video explains 'adultification bias' and highlights some of the stories discussed by Black women and girls during focus-group research conducted by the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty's Initiative on Gender Justice and Opportunity.

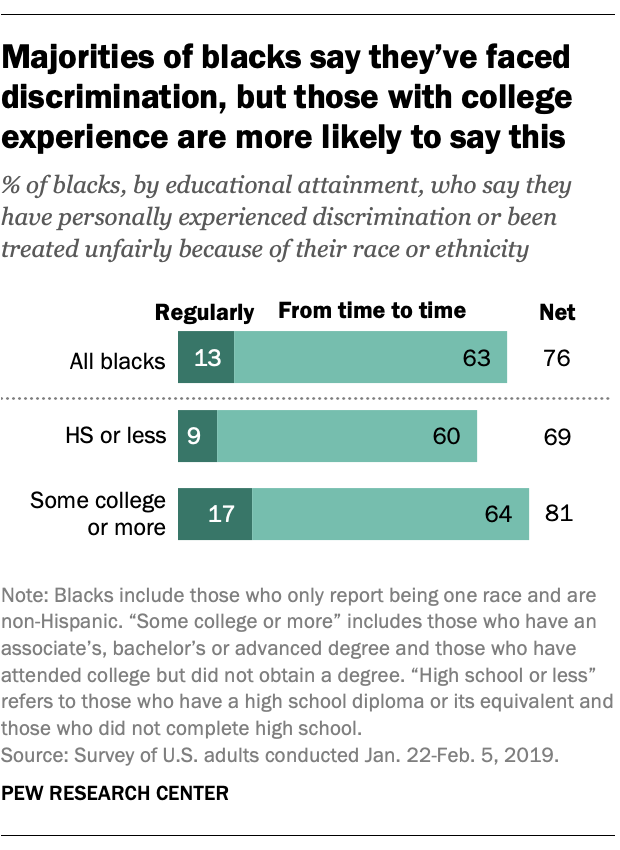

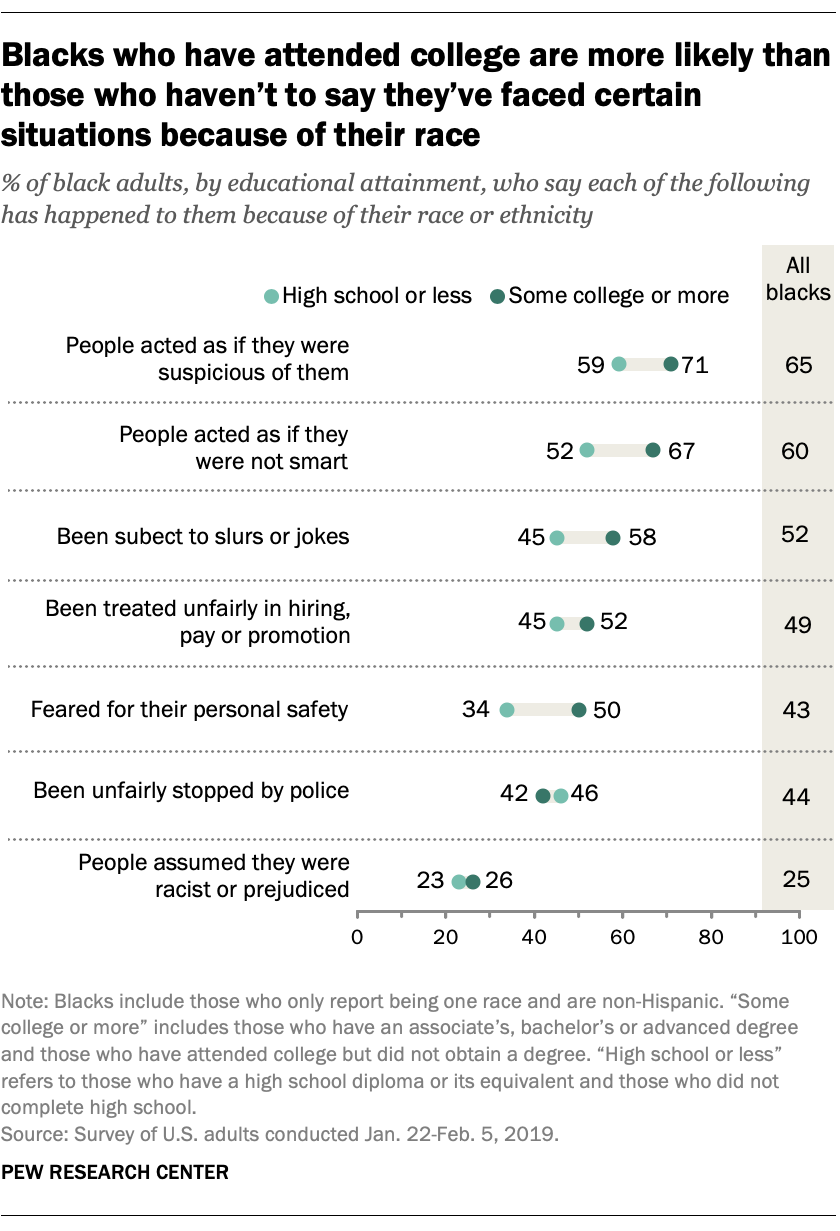

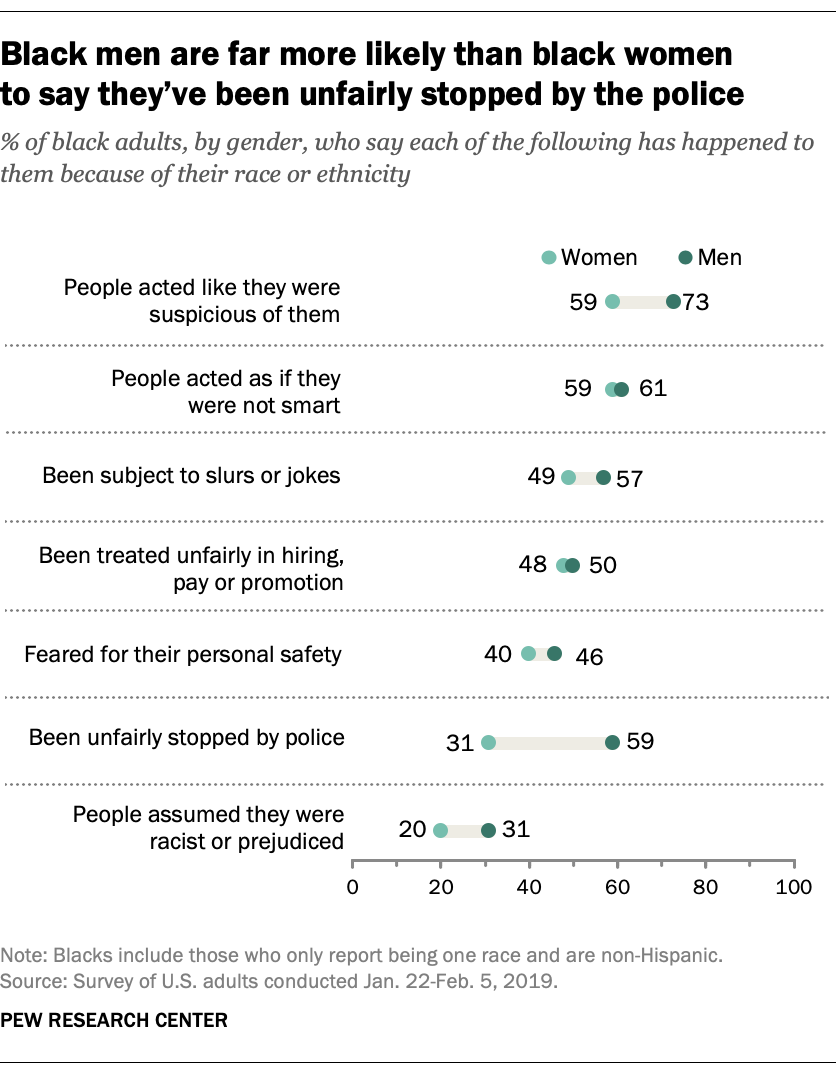

Black American Experiences of Racial Discrimination Vary by Education Level and Gender

Personal experiences with racial discrimination are common for Black Americans. But certain segments within this group – most notably, those who are college educated or male – are more likely to say they’ve faced certain situations because of their race, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

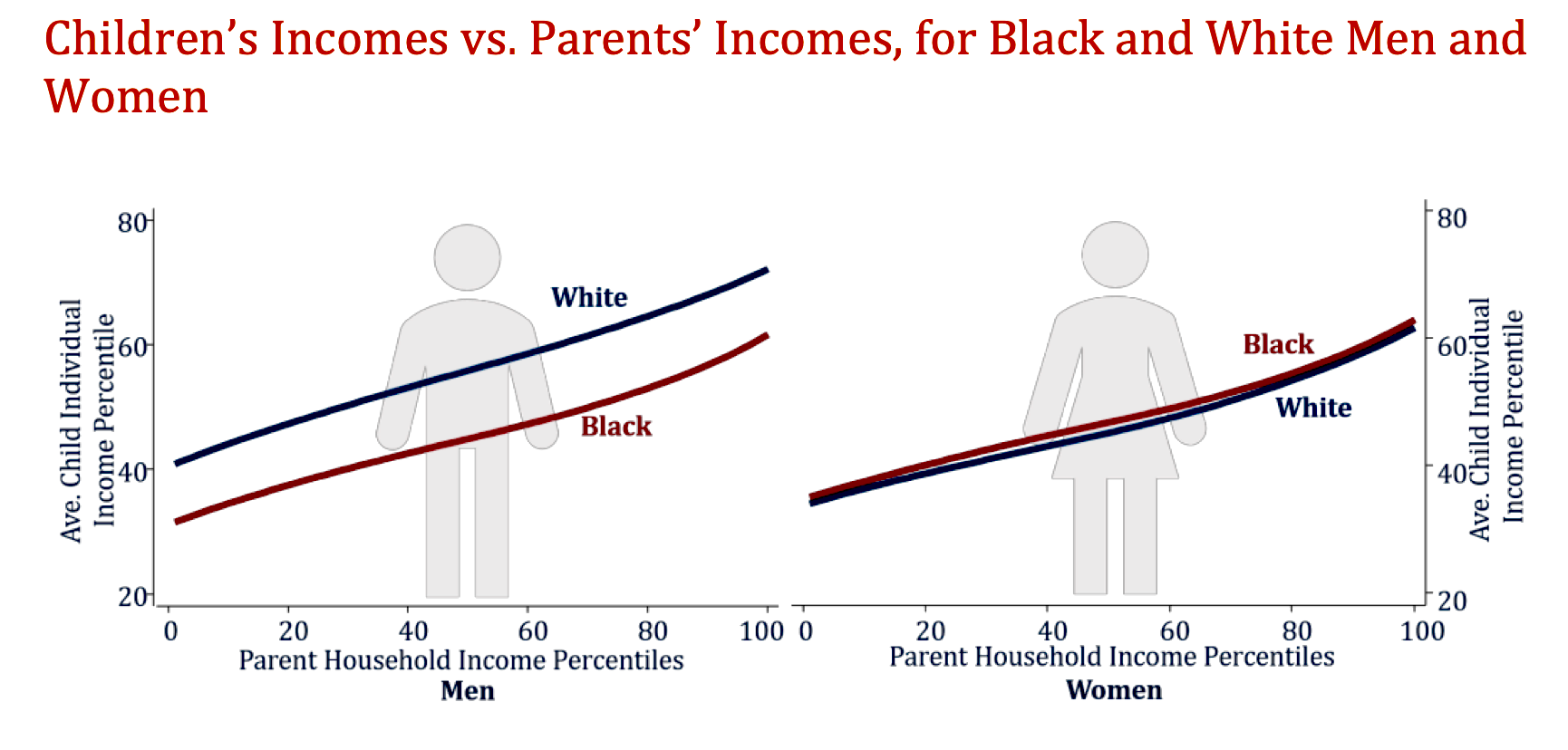

A study led by researchers at Stanford, Harvard and the Census Bureau, found in 99% of neighborhoods in the United States, Black boys earn less in adulthood than white boys who grow up in families with comparable income. According to this study (Chetty, Hendren, Jones, & Porter, (2020),

one of the most prominent theories for why Black and white children have different outcomes is that Black children grow up in different neighborhoods than whites. But, we find large gaps even between Black and white men who grow up in families with comparable income in the same Census tract (small geographic areas that contain about 4,250 people on average). Indeed, the disparities persist even among children who grow up on the same block. These results reveal that differences in neighborhood-level resources, such as the quality of schools, cannot explain the intergenerational gaps between Black and white boys by themselves.

The study also states,

Black-white disparities exist in virtually all regions and neighborhoods. Some of the best metro areas for economic mobility for low-income Black boys are comparable to the worst metro areas for low-income white boys, as shown in the maps below. And Black boys have lower rates of upward mobility than white boys in 99 percent of Census tracts in the country (Chetty et. al, 2020).

This study also found that the Black-white income gap is entirely driven by differences in men’s, not women’s, outcomes. The findings show that among those who grow up in families with comparable incomes, Black men grow up to earn substantially less than the white men. In contrast, Black women earn slightly more than white women, which is found to be conditional on parent income. The study also found little or no gap in wages or work hours between Black and white women.

Contributors and Attributions

Content on this page has multiple licenses. Everything is CC BY-SA other than Black Sexuality and Origins of Discrimination which is CC BY-NC.

- Johnson, Shaheen. (Long Beach City College)

- Hund, Janét. (Long Beach City College)

- Slavery to Liberation: The African American Experience (Encompass) (CC BY-NC 4.0) (Contributed to Black Sexuality and Origins of Discrimination)

- Adultification Bias (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Black Gay Pride Movement (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Matrix of Domination (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- African-American LGBTQ Community (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Works Cited

- Barrera, M. (2002). Hottentot 2000: Jennifer Lopez and her butt. In K. Phillips & B. Reay (Eds), Sexualities in History: A Reader, 411-417. London, UK:Routledge.

- Bowleg, Lisa (2008). "When Black + Lesbian + Woman [Not Equal To] Black Lesbian Woman: The Methodological Challenges of Qualitative and Quantitative Intersectionality Research". Sex Roles. 59 (5–6): 312–325. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9400-z. S2CID 49303030 – via ProQuest.

- Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Jones, M.R., & Porter, S.R. (2020). Race and economic opportunity in the United States: An intergenerational perspective. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(2), 711-783.

- Christy, Kameri; Valandra, Dr. (2017, September). A multi-systems life course perspective of economic abuse. Advances in Social Work. 18 (1): 80–102.

- Collins, P.H. (2000) Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 13.

- Cuvier G.. (n.d.). The Animal Kingdom: Arranged in Conformity with its Organization. (New York, NY: G. & C. & H. Carvill).

- Dang, Alain; Frazer, Somjen (December 2005). "Black Same-Sex Households in the United States" (PDF). National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute National Black Justice Coalition. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- McGruder, K. (2010). Pathologizing Black sexuality: The us experience. In J. Battle & S. Barnes (Eds), Black Sexualities: Probing Powers, Passions, Practices, and Policies, 101-118. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Moore, Mignon (2008). "Gendered Power Relations among Women". American Sociological Review. 73 (2): 335–356. doi:10.1177/000312240807300208. S2CID 143591010 – via ProQuest.

- Moore, Mignon R. (2006). "Lipstick or Timberlands? Meanings of Gender Presentation in Black Lesbian Communities". Signs. 32 (1): 113–139. doi:10.1086/505269. JSTOR 10.1086/505269. S2CID 146712513 – via JSTOR.

- Lewis, Cristopher S. (2012). "Cultivating Black Lesbian Shamelessness: Alice Walker's 'The Color Purple'". Rocky Mountain Review. 66 (2): 158–175. doi:10.1353/rmr.2012.0027. JSTOR 41763555. S2CID 145014258 – via JSTOR.

- Parmer, T. & Gordon, J.J. (2007). Cultural influences on African American sexuality: the role of multiple identities on kinship, power and ideology. Sexual Health: Moral and Cultural Foundations, 3, 173-201. Retrieved from psycnet.apa.org/record/2007-01235-000

- Rachel, S. & Thrasher, C. (2015). A History of ‘Black’ Sexuality in the United States: From Preslavery to the Era of HIV/AIDS to a Vision of HOPE for the Future. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association.

- Reid-Pharr, R. (2009) “Sexuality,” in Encyclopedia of African American History: 1899 to the Present—From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-First Century (Volume 4), ed. Paul Finkelman (Ed), New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Wallenstein, P. (1995). The right to marry: Loving v. Virginia. OAH Magazine of History, 9, no. 2, 41.

- Weinberger, S. (2011). "The birth of a nation" and the making of the naacp. Journal of American Studies, 77-93.