7.5: Social Change and Resistance

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 104073

- Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, & Joy Tsuhako

- Long Beach City College, Cerritos College, & Saddleback College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Origins of the Civil Rights Movement

Education was but one aspect of the nation’s Jim Crow machinery. African Americans had been fighting against systemic racism, a variety of racist policies, cultures and beliefs in all aspects of American life. And while the struggle for Black inclusion had few victories before World War II, the war and the Double V campaign as well as the postwar economic boom led to rising expectations for many African Americans. The Double V campaign was a slogan and drive to promote the fight for democracy in overseas campaigns and at the home front in the United States for African Americans during World War II. The Double V refers to the "V for victory" sign prominently displayed by countries fighting "for victory over aggression, slavery, and tyranny," but adopts a second "V" to represent the double victory for African Americans fighting for freedom overseas and at home. When persistent racism and racial segregation undercut the promise of economic and social mobility, African Americans began mobilizing on an unprecedented scale against the various discriminatory social and legal structures.

While many of the Civil Rights Movement’s most memorable and important moments, such as the sit-ins, freedom rides and especially the March on Washington, occurred in the 1960s, the 1950s and 1940s were a significant decade in the sometimes-tragic, sometimes-triumphant march of civil rights in the United States - resistance which ultimately began with the antebellum movement to abolish slavery in the 1800s. Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Henry Box Brown, Nat Turner and Marcus Garvery are among those who set the stage for the Civil Rights Movement. In 1941, A. Phillip Randolf planned a massive march on Washington to protest against the exclusion that Black Americans faced when applying for defense jobs and access to the New Deal opportunities. In 1953, years before Rosa Parks’ iconic confrontation on a Montgomery city bus, an African American woman named Sarah Keys publicly challenged segregated public transportation. Keys, then serving in the Women’s Army Corps, traveled from her army base in New Jersey back to North Carolina to visit her family. When the bus stopped in North Carolina, the driver asked her to give up her seat for a white customer. Her refusal to do so landed her in jail in 1953 and led to a landmark 1955 decision, Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company, in which the Interstate Commerce Commission ruled that “separate but equal” violated the Interstate Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution. Poorly enforced, it nevertheless gave legal coverage for the freedom riders years later. Moreover, it was a morale-building decision. Six days after the decision was announced, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat in Montgomery.

But if some events encouraged civil rights workers with the promise of progress, others were so savage they convinced activists that they could do nothing but resist. In the summer of 1955, two white men in Mississippi kidnapped and brutally murdered a fourteen-year-old boy, Emmett Till. Till, visiting from Chicago and perhaps unfamiliar with the etiquette of Jim Crow, allegedly whistled at a white woman named Carolyn Bryant. Her husband, Roy Bryant, and another man, J.W. Milam, abducted Till from his relatives’ home, beat him, mutilated him, shot him, and threw his body in the Tallahatchie River. But, the body was found. Emmett’s mother held an open-casket funeral so that Till’s disfigured body could make national news. The men were brought to trial. The evidence was damning, but an all-white jury found the two not guilty. Only months after the decision the two boasted of their crime in Look magazine. For young Black men and women soon to propel the Civil Rights Movement, the Till case was an indelible lesson. Bryant later recanted the story in an interview 60 years later; nonetheless, a trail of white women weaponizing lies against Black men still persists today and can be understood in the "Karen's of 2020."

Four months after Till’s death, Rosa Parks refused to surrender her seat on a Montgomery city bus. Her arrest launched the Montgomery bus boycott, a foundational moment in the civil rights crusade. Montgomery’s public transportation system had longstanding rules that required African American passengers to sit in the back of the bus and give up their seats to white passengers when the buses filled. Parks refused to move on December 1, 1955 and was arrested. She was not the first to protest against the policy by staying seated on a Montgomery bus, but she was the woman around whom Montgomery activists rallied a boycott.

Soon after Parks’ arrest, Montgomery’s Black population, organized behind the recently arrived Baptist minister, Martin Luther King, Jr., and formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to coordinate a widespread boycott. During December 1955 and all of 1956, King’s leadership sustained the boycott and thrust him into the national spotlight. The Supreme Court ruled against Montgomery and on December 20, 1956 King brought the boycott to a successful conclusion, ending segregation on Montgomery’s public transportation and establishing his reputation as a national leader in African American efforts for equal rights.

Motivated by the success of the Montgomery boycott, King and other African American leaders looked for ways to continue the fight. In 1957, King helped create the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Unlike the MIA, which targeted one specific policy in one specific city, the SCLC was a coordinating council to helping civil rights groups across the South plan and sustain boycotts, protests, and assaults on southern Jim Crow laws and practices.

As pressure built, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first such measure passed since Reconstruction. Although the act was nearly compromised away to nothing, although it achieved some gains, such as creating the Civil Rights Commission in the Department of Justice to investigate claims of racial discrimination, it nevertheless signaled that pressure was finally mounting for Americans to finally confront the racial legacy of slavery and discrimination.

Despite successes at both the local and national level, the Civil Rights Movement faced bitter opposition. Those opposed to the movement often used violent tactics to scare and intimidate African Americans and subvert legal rulings and court orders. For example, a year into the Montgomery Bus Boycott, angry white southerners bombed four African American churches as well as the homes of King and fellow civil rights leader E. D. Nixon. Though King, Nixon and the MIA persevered in the face of such violence, it was only a taste of things to come. Such unremitting hostility and violence left the outcome of the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement in doubt. Despite its successes, civil rights activists looked back on the 1950s as a decade of at-best mixed results and incomplete accomplishments. While the bus boycott, Supreme Court rulings and other civil rights activities signaled progress, church bombings, death threats, and stubborn legislators demonstrated the distance that still needed to be traveled.

The Civil Rights Movement (1960s)

So much of the energy and character of “the sixties” emerged from the Civil Rights Movement, which won its greatest victories in the early years of the decade. The movement itself was changing. Many of the civil rights activists pushing for school desegregation in the 1950s were middle-class and middle-aged. In the 1960s, a new student movement arose whose members wanted swifter changes in the segregated South. Confrontational protests, marches, boycotts, and sit-ins accelerated.

The tone of the modern U.S. Civil Rights Movement changed at a Greensboro, North Carolina department store in 1960, when four African American students participated in a “sit-in” at a whites-only Woolworth's lunch counter. The 1960 Greensboro sit-ins were an instrumental action and also the best-known sit-ins of the civil rights movement. They are considered a catalyst to the subsequent sit-in movement, in which 70,000 people participated. Activists sat at segregated lunch counters in an act of defiance, refusing to leave until being served and willing to be ridiculed, attacked, and arrested. It drew resistance, but it forced the desegregation of Woolworth's department stores. It prompted copycat demonstrations across the South. The protests offered evidence that student-led direct action could enact social change and established the civil rights movement’s direction in the forthcoming years.

The following year, civil rights advocates attempted a bolder variation of a “sit-in” when they participated in the Freedom Rides. Activists organized interstate bus rides following a Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation on public buses and trains. The rides intended to test the court’s ruling, which many Southern states had ignored. An interracial group of Freedom Riders boarded buses in Washington D.C. with the intention of sitting in integrated patterns on the buses as they traveled through the Deep South. On the initial rides in May 1961, the riders encountered fierce resistance in Alabama. Angry mobs composed of KKK members attacked riders in Birmingham, burning one of the buses and beating the activists who escaped. Despite the fact that the first riders abandoned their trip and decided to fly to their destination, New Orleans, civil rights activists remained vigilant. Additional Freedom Rides launched through the summer and generated national attention amid additional violent resistance. Ultimately, the Interstate Commerce Commission enforced integrated interstate buses and trains in November 1961.

In the fall of 1961, civil rights activists descended on Albany, a small city in southwest Georgia. A place known for entrenched segregation and racial violence, Albany seemed an unlikely place for Black Americans to rally and demand civil rights gains. The activists there, however, formed the Albany Movement, a coalition of civil rights organizers that included members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, or, “snick”), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the NAACP. But in Albany the movement was stymied by Police Chief Laurie Pritchett, who launched mass arrests but refused to engage in police brutality and bailed out leading officials to avoid negative media attention. It was a peculiar scene, and a lesson for Southern activists.

Despite its defeat, Albany captured much of the energy of the civil rights movement. The Albany Movement included elements of the Christian commitment to social justice in its platform, with activists stating that all people were “of equal worth” in God’s family and that “no man may discriminate against or exploit another.” In many instances in the 1960s, Black Christianity propelled civil rights advocates to action and demonstrated the significance of religion to the broader civil rights movement. King’s rise to prominence underscored the role that African American religious figures played in the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. Protestors sang hymns and spirituals as they marched. Preachers rallied the people with messages of justice and hope. Churches hosted meetings, prayer vigils, and conferences on nonviolent resistance. The moral thrust of the movement strengthened African American activists while also confronting white society by framing segregation as a moral evil.

As the Civil Rights Movement garnered more followers and more attention, white resistance stiffened. In October 1962, James Meredith became the first African American student to enroll at the University of Mississippi. Meredith’s enrollment sparked riots on the Oxford campus, prompting President John F. Kennedy to send in U.S. Marshals and National Guardsmen to maintain order. On an evening known infamously as the Battle of Ole Miss, segregationists clashed with troops in the middle of campus, resulting in two deaths and hundreds of injuries. Violence despite federal intervention served as a reminder of the strength of white resistance to the Civil Rights Movement, particularly in the realm of education.

The following year, 1963, was perhaps the decade’s most eventful year for civil rights. In April and May, the SCLC organized the Birmingham Campaign, a broad campaign of direct action aiming to topple segregation in Alabama’s largest city. Activists used business boycotts, sit-ins, and peaceful marches as part of the campaign. SCLC leader Martin Luther King Jr. was jailed, prompting his famous handwritten Letter from Birmingham Jail urging not only his nonviolent approach but active confrontation to directly challenge injustice. The campaign further added to King’s national reputation and featured powerful photographs and video footage of white police officers using fire hoses and attack dogs on young African American protesters. It also yielded an agreement to desegregate public accommodations in the city; activists in Birmingham scored a victory for civil rights and drew international praise for the nonviolent approach in the face of police-sanctioned violence and bombings.

White resistance magnified. In June, Alabama Governor George Wallace famously stood in the door of a classroom building in a symbolic attempt to halt integration at the University of Alabama. President Kennedy addressed the nation that evening, criticizing Wallace and calling for a comprehensive civil rights bill. A day later, civil rights leader Medgar Evers was assassinated at his home in Jackson, Mississippi. Civil rights leaders gathered in August 1963 for the March on Washington. The March called for, among other things, civil rights legislation, school integration, an end to discrimination by public and private employers, job training for the unemployed, and a raise in the minimum wage. On the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, an internationally renowned call for civil rights and against racism that raised the movement’s profile to unprecedented heights. The year would end on a somber note with the assassination of President Kennedy, a public figure considered an important ally of civil rights, but it did not halt the civil rights movement.

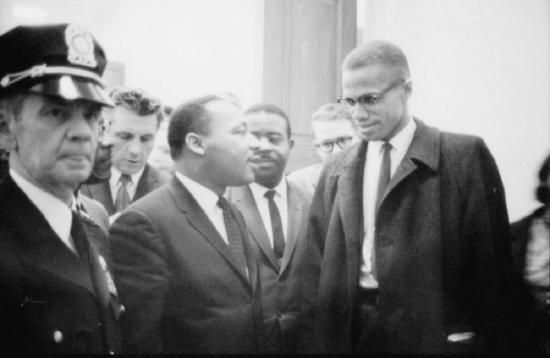

(CC PDM 1.0; National Archives via Wikimedia)

President Lyndon Johnson embraced the Civil Rights Movement, though somewhat reluctantly as he navigated between white Southern segregationists and activists such as Dr. King. The following summer, Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, widely considered to be among the most important pieces of civil rights legislation in American history. The comprehensive act barred segregation in public accommodations and outlawed discrimination based on race, ethnicity, gender, and national or religious origin.

Direct action continued through the summer, as student-run organizations like SNCC and CORE (The Congress of Racial Equality) helped with the Freedom Summer in Mississippi, a drive to register African American voters in a state with an ugly history of discrimination. Freedom Summer campaigners set up schools for African American children and endured intimidation tactics. Even with progress, violent resistance against civil rights continued, particularly in regions with longstanding traditions of segregation.

Direct action and resistance to such action continued in March 1965, when activists attempted to march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, with the support of prominent civil rights leaders on behalf of local African American voting rights. In a narrative that had become familiar, “Bloody Sunday” featured peaceful protesters attacked by white law enforcement with batons and tear gas. After they were turned away violently a second time, marchers finally made the 70-mile trek to the state capitol later in the month. Coverage of the first march prompted President Johnson to present the bill that became the Voting Rights Act of 1965, an act that abolished voting discrimination in federal, state, and local elections with an eye on African American enfranchisement in the South. In two consecutive years, landmark pieces of legislation had helped to weaken de jure segregation and disenfranchisement in America.

And then things began to stall. Days after the ratification of the Voting Rights Act, race riots broke out in the Watts District of Los Angeles. Rioting in Watts stemmed from local African American frustrations with residential segregation, police brutality, and racial profiling. Waves of riots would rock American cities every summer thereafter. Particularly destructive riots occurred in 1967—two summers later—in Newark and Detroit. Each resulted in deaths, injuries, arrests, and millions of dollars in property damage. In spite of Black achievements, inner-city problems persisted for many African Americans. The phenomenon of white flight—when whites in metropolitan areas fled city centers for the suburbs—often resulted in “re-segregated” residential patterns. Limited access to economic and social opportunities in urban areas bred discord. In addition to reminding the nation that the Civil Rights Movement was a complex, ongoing event without a concrete endpoint, the unrest in northern cities reinforced the notion that the struggle did not occur solely in the South. Many Americans also viewed the riots as an indictment of the Great Society, President Johnson’s sweeping agenda of domestic programs that sought to remedy inner-city ills by offering better access to education, jobs, medical care, housing, and other forms of social welfare. This would mark the decline of the Civil Rights Movement.

Black Power Movement

By the late 1960s, SNCC, led by figures such as Stokely Carmichael who later changed his name to Kwame Ture, had expelled its white members and shunned the interracial effort in the rural South, focusing instead on injustices in northern urban areas. After President Johnson refused to take up the cause of the Black delegates in the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party at the 1964 Democratic National Convention, SNCC activists became frustrated with institutional tactics and turned away from the organization’s founding principle of nonviolence over the course of the next year. This evolving, more aggressive movement called for African Americans to play a dominant role in cultivating Black institutions and articulating Black interests rather than relying on interracial, moderate approaches. At a June 1966 civil rights march, Carmichael told the crowd, “What we gonna start saying now is Black power!” The slogan not only resonated with audiences, it also stood in direct contrast to King’s “Freedom Now!” campaign. The political slogan of Black power could encompass many meanings, but at its core stood for the self-determination of Blacks in political, economic, and social organizations.

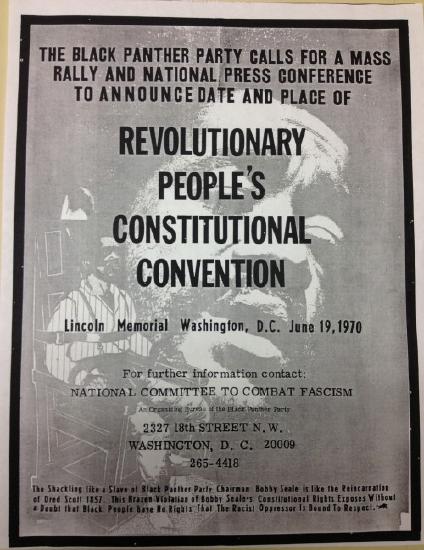

While Carmichael asserted that “Black power meant Black people coming together to form a political force,” to others it meant violence. In 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale formed the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California. The Black Panthers became the standard-bearers for direct action and self-defense, using the concept of decolonization in their drive to liberate Black communities from white power structures. The revolutionary organization also sought reparations and exemptions for Black men from the military draft. Citing police brutality and racist governmental policies, the Panthers aligned themselves with the “other people of color in the world” against whom America was fighting abroad. Although it was perhaps most well-known for its open display of weapons, military-style dress, and Black nationalist beliefs, the Party’s 10-Point Plan also included employment, housing, and education. The Black Panthers worked in local communities to run “survival programs” that provided food, clothing, medical treatment, and drug rehabilitation. They focused on modes of resistance that empowered Black activists on their own terms.

By 1968, the Civil Rights Movement looked quite different from the one that had emerged out of the 1960 Greensboro sit-ins. The movement had never been monolithic, but prominent, competing ideologies had now fractured it significantly. King’s assassination on a Memphis hotel room balcony in April sparked another wave of riots in over 100 American cities and brought an abrupt, tragic end to the life of the movement’s most famous figure. Only a week after his assassination, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, another significant piece of federal legislation that outlawed housing discrimination. Two months later, on June 6, Robert Kennedy was gunned down in a Los Angeles hotel while campaigning to be the Democratic candidate for President. The assassinations of both national leaders in succession created a sense of national anger and dissolution.

The frustration prompted dozens of national protest organizations to converge on the Democratic National Convention in Chicago at the end of August. A bitterly fractured Democratic Party gathered to assemble a passable platform and nominate a broadly acceptable presidential candidate. Outside the convention hall, numerous student and radical groups—the most prominent being Students for a Democratic Society and the Youth International Party—identified the conference as an ideal venue for demonstrations against the Vietnam War and planned massive protests in Chicago’s public spaces. Initial protests were peaceful, but the situation quickly soured as police issued stern threats, and young people began to taunt and goad officials. Many of the assembled students had protest and sit-in experiences only in the relative safe havens of college campuses, and were unaccustomed to the heavily armed, big-city police force, accompanied by National Guard troops in full riot gear. Attendees recounted vicious beatings at the hands of police and Guardsmen, but many young people—convinced that much public sympathy could be won via images of brutality against unarmed protesters—continued stoking the violence. Clashes spilled from the parks into city streets, and eventually the smell of tear gas penetrated upper floors of the opulent hotels hosting Democratic delegates.

The ongoing police brutality against the protesters overshadowed the convention and culminated in an internationally televised standoff in front of the Hilton Hotel, where policeman beat protestors chanting, “the whole world is watching!” For many on both sides, the Chicago riots engendered a growing sense of the chaos rocking American life. The disparity in force between students and police frightened some radicals out of advocacy for revolutionary violence, while some officers began questioning the war and those who waged it. Many more, though, saw disorder and chaos where once they had seen idealism and progress. Ultimately, the violence of 1968 was not the death knell of a struggle simply for the end of Black-white segregation, but rather a moment of transition that pointed to the continuation of past oppression and foreshadowed many of the challenges of the future. At decade’s end, civil rights advocates could take pride in significant gains while acknowledging that many of the nation’s racial issues remained unresolved.

Black Lives Matter Movement

Black Lives Matter (BLM) is a decentralized political and social movement advocating for non-violent civil disobedience in protest against incidents of police brutality and all racially motivated violence against Black people. The broader movement and its related organizations typically advocate against police violence towards Black people as well as for various other policy changes considered to be related to Black liberation.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=515&height=386)

In July 2013, the movement began with the use of the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter on social media after the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of African-American teen Trayvon Martin 17 months earlier in February 2012. The movement became nationally recognized for street demonstrations following the 2014 deaths of two African Americans, that of Michael Brown—resulting in protests and unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, a city near St. Louis—and Eric Garner in New York City. Since the Ferguson protests, participants in the movement have demonstrated against the deaths of numerous other African Americans by police actions or while in police custody. In the summer of 2015, Black Lives Matter activists became involved in the 2016 United States presidential election. The originators of the hashtag and call to action, Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi, expanded their project into a national network of over 30 local chapters between 2014 and 2016. The overall Black Lives Matter movement is a decentralized network of activists with no formal hierarchy.

The movement returned to national headlines and gained further international attention during the global George Floyd protests in 2020 following the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. An estimated 15 million to 26 million people, although not all are members or part of the organization, participated in the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests in the United States, making Black Lives Matter one of the largest movements in United States history. The movement has advocated to defund the police and invest directly into Black communities and alternative emergency response models.

The popularity of Black Lives Matter has rapidly shifted over time. Whereas public opinion on Black Lives Matter was net negative in 2018, it grew increasingly popular through 2019 and 2020. A June 2020 Pew Research Center poll found that the majority of Americans, across all racial and ethnic groups, have expressed support for the Black Lives Matter movement.

Black Social Media: A New Age Revolution

A new age Black revolution is currently waging on YouTube and Black Twitter by passionate African American social media personalities determined to help Black people defeat and rise above white supremacy’s boundaries. In recent years, social media sites like Facebook,Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram, BlogTalkRadio, and YouTube have reformatted Black radicalism in the United States by providing zealous African American activists with an online platform to boldly express their concerns and gain a following by using the Internet. As a result, significant shifts in Black revolutionary thought or consciousness and new protest methods have developed in combination with the rapid growth in human dependency on computer capabilities. The new virtual home for Black resistance to white-led racial oppression is rooted inside the Black radical tradition of remaining committed to an idealized, Black liberationist goal of securing self-regulating social, political, cultural, and economic freedom for people of African descent worldwide.

Black Twitter is an online subculture largely consisting of Black users on the social network Twitter focused on issues of interest to the Black community, particularly in the United States. Black Twitter has been describe as "a collective of active, primarily African-American Twitter users who have created a virtual community ... [and are] proving adept at bringing about a wide range of sociopolitical changes" (Jones, 2013). Although Black Twitter has a strong Black American user base, other people and groups are able to be a part of this social media circle through commonalities in shared experiences and reactions to such online. Calling out cultural appropriation was a chief focus of the space in the early 2010s.

Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\): The aftermath of the death of Trayvon Martin brought Black Twitter to wider public attention. (CC BY 2.0; ann harkness via Flickr)

The thought leaders of Black social media are both eagerly and often hesitantly referred to as spearheads of the Black Conscious Community. The Black Conscious Community is a conglomerate of sporadically allied African Americans who advocate replacing mainstream Black philosophies and institutions with Afrocentric and Black Nationalist ideas and action. The YouTubers of focus were chosen due to their loose connections and because they are among the most influential and thought-provoking in their justifications for the complete transformation of the psyche and physical reality of all people of African descent. Many of the Black YouTube radicals are often offended by the term and categorization of “YouTube Revolutionary” or “Web-Oblutionary” because they believe such titles diminish the importance of their online and in-person work. Yet, the label is appropriate and reflects unique characteristics that make the online Black militants’ important voices in the current political and social media landscape. The new virtual presence in Black radical thinking and action amassed by these YouTube radicals are worthy of serious scholarly study because they represent a critical stage of development in Black revolutionary history and consciousness.

This section is licensed CC BY-NC. Attribution: Slavery to Liberation: The African American Experience (Encompass) (CC BY-NC 4.0)

Contributors and Attributions

Content on this page has multiple licenses. Everything is CC BY-SA other than Black Social Media: A New Age Revolution which is CC BY-NC.

- Johnson, Shaheen. (Long Beach City College)

- Hund, Janét. (Long Beach City College)

- Black Lives Matter (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Black Panther Party (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Black Power (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Black Twitter (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Civil Rights Act of 1968 (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Double V Campaign (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- United States History 2 (Lumen) (CC BY-SA 4.0)

- Greensboro Sit-Ins (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Nation of Islam (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Slavery to Liberation: The African American Experience (Encompass) (CC BY-NC 4.0) (Contributed to: Black Social Media: A New Age Revolution)

- Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Students for a Democratic Society (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Ten-Point Program (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Voting Rights Act of 1965 (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Youth International Party (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)