2.1: The Scientific Method and Comparative Politics

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 150425

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Consider the factors which make political science, and thereby comparative politics, a science.

- Identify and be able to describe the steps and key terms used in the scientific method.

Introduction

When many people consider the field of science, they may think of laboratories filled with clinicians in white lab coats, chemical experiments with bubbling vials, or vast chalkboards of mathematical equations. Science can actually be divided into small components.

- Hard sciences, such as chemistry, mathematics, and physics, work to advance scientific understanding in the natural or physical sciences.

- Soft sciences work to advance scientific understanding of human behavior, institutions, society, government, decision making, and power. A subfield is the social sciences, which scientifically study human society and relationships, such as history, psychology, politics, etc.

In considering the different challenges facing hard and soft sciences, Physicist Heinz Pagels called the social sciences the “sciences of complexity,” and said further, “the nations and people who master the new sciences of complexity will become the economic, cultural, and political superpowers of the 21st century" (Pagels, 1988). As science is defined as the systematic and organized approach to any area of inquiry, and utilizes scientific methods to acquire and build a body of knowledge, political science embodies the essence of the scientific method and possesses deep foundations for scientific tools and theory formation.

“Comparative politics is a subfield of study within political science that seeks to advance understanding of political structures from around the world in an organized, methodological, and clear way”. In observing countries and their similarities and differences, we need to be able to distinguish between actions or decisions that are happening systematically from actions or decisions that may happen randomly. To this end, political scientists follow and rely on the rules of scientific inquiry to conduct their research.

Why is Political Science a Science?

Thucydides, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle provided observations on their political worlds and ideas about why states and political actors may behave the way they do. The modern conception of Political Science is one that, like other social sciences, follows the scientific method and is based on a philosophic tradition regarding the nature of inquiry. Beginning in the late 1800s, scholars began attempting to treat political science as a hard science that could utilize the scientific method.

A seminal work in the field of Political Science that sought to describe the features of scientific research within the field came from Gary King, Robert Keohane and Sidney Verba, who wrote, Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research in 1994. Although the book was discussing political science in relation to qualitative research methods, they also spent a generous amount of time considering what scientific research in political science looks like.

According to King, Keohane, and Verba (1994), scientific research has four main characteristics.

- First, make descriptive or causal inferences. An inference is a process of drawing a conclusion about an unobserved phenomenon, based on observed (empirical) information. Note-- the accumulation of facts, by itself, does not make such an effort scientific. In order for a study to be scientific, it requires the additional step of going beyond the immediately observable information. The process of making inferences help us learn about the unobserved fact by describing it based on empirical information. For example, we cannot directly observe democracy. Yet, political scientists have identified various tenets and characteristics of democratic nations, to the extent that we can describe such a concept. We can also learn the causal effects from the observed information, such as studying the cause and effects of a war.

- Second, the procedures of scientific research must be public. Scientific research relies on 'explicit, codified, and public methods' so that the reliability of a study can be assessed effectively. The process of gathering and analyzing information/data must be reliable in order to make inferences. For example, as a condition for publication, authors must share data files or survey questionnaires to ensure that anyone could possibly replicate the work to assess its reliability as well as to evaluate the appropriateness of the method being used in such work.

- Third, the process of making inferences is imperfect, and the conclusions of scientific research are uncertain. Researchers must be aware of a reasonable estimate of uncertainty in their work to ensure that they can effectively interpret their conclusions. By definition, inferences without some level of uncertainty are not scientific.

- Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the content of scientific research is the method. Whether one’s research is scientific or not is determined by the way it is conducted as opposed to the subject matter of what is being studied. Validity is dependent on how closely one follows rules and procedures. Simply put, one can virtually study anything in a scientific manner as long as the researcher follows the rules of inference and scientific methods.

The Scientific Method

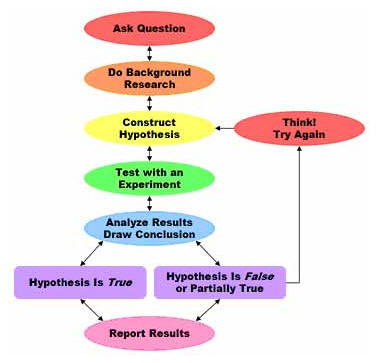

If you have ever enrolled in a science course, you have likely encountered the scientific method, a process by which knowledge is acquired through a sequence of steps, which generally include the following components: question, observation, hypothesis, testing of the hypothesis, analysis of the outcomes, and reporting of the findings. Ideally, the use of the scientific method will build a body of knowledge and culminate in the formation of inferences and potential theories for why/how phenomena exist or occur.

Broadly speaking, the scientific method within political science will involve the following steps:

- Research question: Develop a clear, focused, and relevant research question.

- Literature review: Research the context, background information, and previous research regarding the research question. The literature review is a section of your research paper or research process, where key sources and previous research are discussed. From this work, you are able to have a full scope of understanding of all previous work performed on your topic, which will enhance your knowledge in the field.

- Theory and hypothesis development: Develop a theory that explains a potential answer to your research question. A theory is a statement that explains how the world works based on experience and observation. From the theory, you will construct hypotheses to test the theory. A hypothesis, or set of hypotheses, will describe, in very clear terms, what you expect will happen given the circumstances. Within the hypothesis, variables will be identified. Political scientists are concerned with cause-and-effect relationships, and divide the variables into two categories:

- independent variables (explanatory variables) are the cause, and independent of other variables under consideration in a study.

- dependent variables (outcome variables) are the assumed effect, their values will (presumably) depend on the changes in the independent variables.

- Testing: A political scientist will test the hypothesis, or hypotheses, through observation of the relationship between the designated variables.

- Analysis: When the testing is complete, political scientists review their results and draw conclusions about the findings.

- Was the hypothesis correct? If so, report the success of the findings.

- Was the hypothesis incorrect? That’s okay! A famous quip in this field is, 'no finding is still a finding.' If the hypothesis was not proven true, or fully true, then it is back to the drawing board to rethink a new hypothesis and do the testing again.

- Reporting of findings: Reporting results, whether the hypothesis is true, partially true, or outright false, is critical to the advancement of the overall field. Typically, researchers will publish their findings so the findings are public and transparent, and others may continue research in that area.

Image: California State University--Northridge

Image: California State University--Northridge

Step One: The Research Question

Before a researcher can start thinking about describing or explaining a phenomenon, they must start with a question about the phenomenon of interest. So, how do you determine what characteristics define a good political research question?

First, a substantive and quality political science question needs to be relevant to the real political world. It does not need to only address current political affairs. In fact, many political scientists study historical events and past political behaviors. However, the results of political science research are often relevant to the current political environment and may come with policy implications. Second, as an academic discipline, political science research is a means through which the discipline grows in terms of its knowledge about the political realm.

Overall, a political science research question must be an important point. Indeed, the answer to such a statement has a chance of being wrong. In other words, a research question has to be falsifiable. Falsifiability, coined by philosopher of science, Karl Popper, is defined as the ability for a statement to be logically contradicted through empirical testing. (With empirical analysis being defined as the basis of an experiment, experience, or observation).

Some questions are inherently non-falsifiable, meaning the question cannot be proven true or false under present circumstances. This stance is particularly true in subjective questions (e.g. Are oranges better than lemons?) or technical limitations (Do angry ninja-robots live in Alpha Centauri?).

Consider the subjective example in political science: Which one is better, North Dakota or South Dakota?

This question is subjective. If the question was more refined and not simply a case of some abstract definition of ‘better than,’ perhaps the researcher could find something that could be proven:

Which state is more economically productive, North or South Dakota?

Now, the researcher could lay out metrics for what constitutes economically productive, and try to build from there.

Technical limitations are a problem in political science. Let's consider the question: Does investing in a country’s education system always mean it will eventually become democratic? There are two problems with this question. First, making a blanket statement that investing in education always leads to democracy is difficult to measure. Will you be able to test every situation and circumstance where education systems are invested in and democracy happens? Second, there’s an issue with the word ‘eventually.’ A country that invests heavily in education could become democratic 700 years from now. If the time span ends up being 700 years, we cannot truly infer that it was the initial investment in education that was the cause of that county’s democratic transition.

Step Two: The Literature Review

Once you’ve found the research question, consider how much you actually know about the topic, and do some research about previous studies on the topic. In most cases, the literature review will have its own introduction, body, and conclusion. The introduction will explain the context of the research question. The body will summarize and synthesize all the research, ideally in either chronological, thematic, methodological, or theoretical order.

For chronological order, begin with the early research and end in the most recent research on a topic. If the research contains a number of interrelated themes, categorize the research based on its theme. Finally, you can organize the review by previous theories. In general, it’s important to consider the best way to showcase, summarize and synthesize previous research so it is clear to the readers and other scholars interested in the topic.

Step Three: Theory and Hypothesis Development

After the literature review, it is time to consider the theories and hypotheses that you will be using. Usually, the theory helps build your hypotheses for the study.

A scientific theory consists of a set of assumptions, hypotheses, and independent (explanatory) and dependent (outcome) variables. First, assumptions are statements that are taken for granted. For example, many international relations scholars assume that the world is anarchic, meaning that there is no meaningful central authority to enforce the rules of law. Scientific researchers are implicitly assuming that an objective truth exists. If we were to start a scientific inquiry by testing the assumption about the existence of an objective truth, we will never be able to proceed with the actual question of interest since such an assumption is not really testable. Again, we typically do not challenge a set of assumptions in scientific research.

Political science research involves both generating and testing hypotheses. Researchers may start by observing many cases that relate to a topic of inquiry. There are several methods

- inductive reasoning--scientists look at specific situations and attempt to form a hypothesis

- deductive reasoning--occurs when political scientists make an inference and then test its truth using evidence and observations

(To learn more about these types of reasoning, including examples, visit Live Science's Deductive reasoning vs. Inductive reasoning)

A hypothesis is a specific and testable prediction of what you think will happen. Variables will be identified. Remember, a variable is a factor or object that can vary or change. Again, as political scientists are concerned with cause-and-effect relationships, they will divide the variables into two categories: independent variables (explanatory variables) are the cause, and these variables are independent of other variables under consideration in a study. Dependent variables (outcome variables) are the assumed effect, their values will (presumably) depend on the changes in the independent variables.

Steps Four and Five: Testing and Analysis

The testing of a theory and set of hypotheses will depend on the research method you decide to employ. For our purposes, the basic research approaches of interest will be the experimental method, the statistical method, case study method, and the comparative method. Each one of these methods involves research questions, the use of theories to inform our understanding of the research problem, hypothesis testing, and/or hypothesis generation.

Similarly, an analysis of outcomes can be reliant on the research methodologies employed and is critical to the advancement of the field of political science. It is important to interpret findings as accurately and objectively as possible in order to lay the foundations for further research to occur.

Step Six: Reporting of Findings

A critical feature of the scientific method is to report your research findings. Not all research will result in publication. Sometimes research, if not published, is shared through research conferences, books, articles, or digital media. Overall, the sharing of information helps lend others to further research into your topic, or helps spawn new and interesting directions of research.

Interestingly, one can compare a world where research is shared versus where it was not shared. During the flu pandemic of 1918, many countries did not have freedom of the press, including the United States, which had implemented the Sedition Acts in the midst of World War I. Thus, many doctors around the world were not able to effectively communicate. Inundated with swarms of patients, flummoxed by the nature of the flu that was killing young, healthy adults, but largely sparing older individuals, doctors were trying all sorts of treatment methods, but were unable to broadly share their results of what worked and didn’t work well for treatment.

Contrast this scenario with the COVID-19 pandemic, many doctors were working on treatment plans worldwide, and were able to share their ideas on how to best treat the disease. Initially, there was a heavy reliance on ventilators. In time, some doctors found that repositioning patients on their stomachs could bide time for the patient to recover without having to resort to a ventilator right away.

All told, the sharing of results is critical to learning about a research area or question. If scientists, as well as political scientists, are unable to share what they’ve learned, it can stall the advancement of knowledge altogether.