Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Distinguish the functions of legislative, executive and judicial branches.

- Define Electoral Systems and Political Parties.

- Determine the implications of political party composition and organization.

Introduction

Some institutions tend to be common within democracies. Each building block has distinct functions, wielding distinct forms of power and operating within what political scientists would call a separation of powers with checks and balances. Separation of powers divides government functions into three areas:

- the legislature, tasked primarily with the making of laws

- the executive, who carries out or enforces these laws

- the judiciary, tasked with interpreting the constitutionality of laws

These three institutions generally operate under a process of checks and balances, which is a system that attempts to ensure that no one branch can become too powerful. Other hallmark institutions of democracies are their electoral systems and the presence of political parties, which are discussed later in this section.

Electoral systems are voting systems that provide a set of rules that dictate how elections (and other voting initiatives) are conducted and how results are determined and communicated. Political parties are groups of people who are organized under shared values to get their candidates elected to office to exercise political authority. All of these institutions, taken together, contribute to the many unique democracies that exist today.

Executive, Legislative and Judicial

While some elements and characteristics of democracy vary, one constant commonality is the separation of powers among institutions within governments. Separation of powers and checks and balances provides for power to be spread throughout multiple branches of government so that no single branch has too much power. Instead, all branches are empowered with their own institutionalized powers.

The legislative branch is tasked with performing three main functions:(1) making and revising laws; (2) providing administrative oversight to ensure laws are being properly executed; (3) and providing representation of the constituents to the government. There are three main types of legislatures worth noting.

- Consultative legislature is one where the legislature advises the leader, or group of leaders, on issues relating to laws and their application. Members could either be elected or appointed.

- Parliamentary legislature is one where members are elected by the people, enact laws on their behalf, and also serve as the executive branch of government.

- Congressional legislature is one where groups of legislators, elected by the people, make laws and share powers with other branches within the government. An example would be the United States.

Interestingly, while most of the legislatures in North and South America are congressional legislatures (with the exception of Canada, which has a parliamentary legislature), European legislatures have tended to be parliamentary. The main difference between the two systems is in how they structure their power. In the congressional system, power is divided for main functions, but shared with others. In the parliamentary system, the legislative body serves as both the legislative and the executive branches. The head of government, chosen by whoever the majority political party is at that time, attempts to build a majority group in the legislature to get laws made. If the leader is unable to build coalitions to reach agreements on legislation, laws cannot get made.

Within democracies, the executive branch is typically made up of a singular leader, a leader with an assistant (vice-president), or a small group of leaders who have institutional powers, and serves as both the head of government and the head of state. In their capacity as head of government, chief executives must run and manage the day-to-day business of the state. As the head of state, the chief executive must represent the country in the global arena, for formal gatherings to dictate policies as well as for ceremonial responsibilities.

The final “building block” of government to identify is the judiciary or Judicial Branch, where laws can be interpreted and enforced. In some countries, such as the United States, the judiciary is the third branch of government. In other countries, the judiciary shares the responsibility of interpreting the constitutionality of laws with other branches of government. In authoritarian regimes, the judiciary tends to be subservient to the executive and legislative branches. In democracies, the judiciary upholds the separation of powers, so no one branch can become too powerful.

In the U.S., the Supreme Court has the sole power of judicial review, which is the ability to interpret the constitutionality of laws. In doing so, they have the ability to overturn decisions made by lesser courts. Other countries have a similar process.

Electoral Systems & Political Parties

As described previously, electoral systems are voting systems. An electoral system provides a set of rules that dictate how elections (and other voting initiatives) are conducted and how results are determined and communicated. Elections are the mechanism through which leaders get chosen around the world. These rules can include when elections occur, who is allowed to vote, who is allowed to run as a candidate, how ballots are collected and can be cast, how ballots are counted, and what constitutes a victory. Usually, voting rules are set forth by constitutions, election laws, or other legal mandates/establishments. There are a number of different types of electoral systems.

- A plurality voting system is one where the candidate who gets the most votes, wins. There is no requirement to attain a majority, so this system can sometimes be called the first-past-the-post system. It's the second most common election type for presidential elections and elections for legislative members around the world.

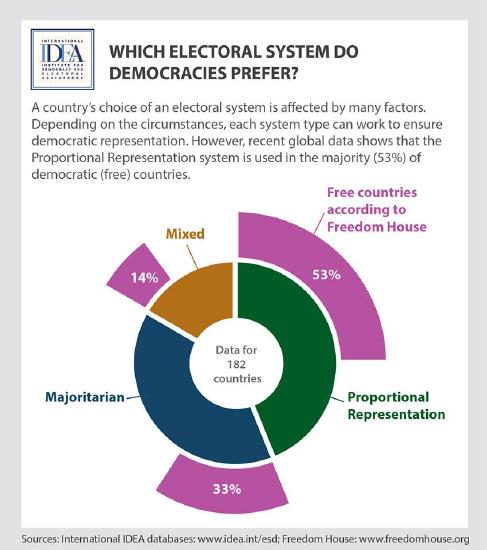

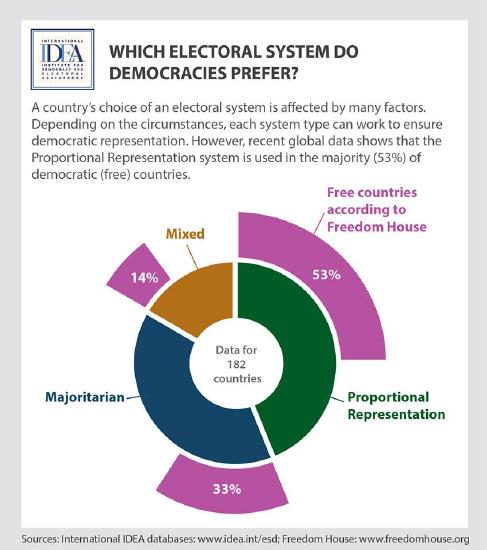

- The majoritarian voting system is one where candidates must win a majority in order to win the election. If they do not win a majority, there needs to be a runoff election.

- The proportional voting system is one where voting options reflect geographical or political divisions in the population to enable proportional leadership when elected. For instance, if 10% of the population are members of Political Party A, then the country’s legislature will allow for 10% of its membership to reflect this.

- Some countries employ mixed voting systems, which can combine the use of any of the aforementioned election systems, using different systems for different types of elections, i.e. presidential versus legislative.

Date of publication November 2016

Political parties play am important role in elections and how political agendas are accomplished in different countries. Often, parties use a label to indicate group leaders as well as their core values/priorities. It is interesting to consider political parties in the context of U.S. democracy. Originally, the country didn’t plan for parties. In fact, political leaders warned against them as deleterious.

Political parties are not altogether helpful in democracies, but can be mitigated by means of an extended political sphere. In other words, if factions must exist, it is better to have too many than too few. That way, as U.S. President George Washington stated in his farewell address, myriad factions make it “less likely…that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens.”

Political parties can lead to observably intense partisanship, measured quantitatively by the lack of compromise. An example can be found in former U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s proverbial “11th Commandment” which posited “Republicans should never {publicly} criticize fellow Republicans”. Arguably, the impeachment of former president Bill Clinton and both impeachments of former president Donald Trump all ended with no political consequence. Specifically, while both Clinton and Trump were impeached in the House of Representatives along almost unanimous party lines, neither were convicted in the Senate in what was likewise near-unanimous party-line votes.

Katz classifies political parties by:

- the number of parties competing--The number of parties depends upon the electoral formula and the number of deputies from each district. A large-district, proportional representation electoral system generally yields the greatest number of parties.

- orientation-ideological/national vs. local/service--The orientation depends upon the electoral formula. Generally, proportional representation systems yield parties with an ideological orientation.

- internal unity--It depends upon the given electoral formula. If there are intra-party preference votes (primaries), there is likely to be more internal disunity; particularly, there will be diffused leadership. If resources are so diffused that each candidate must build their own resources and following, then a fractionalized party is likely.