Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Evaluate the “logic of collective action” and challenges to cooperation

- Analyze the different factors that can facilitate collective action

The Logic of Collective Action

Collective action hinges on coordination and cooperation, and political scientists have employed many frameworks and utilized the tools of game theory to explore the conditions under which collective action occurs as well as when that action is likely to be successful.

One of the most influential frameworks for understanding collective action is Mancur Olson’s The Logic of Collective Action (1965), which argues that collective action failures are to be expected given rational and self-interested individuals. Such people are disinclined to organize and contribute to the production of a public or collective good, while letting others do the hard work of achieving the goal, then enjoy the fruits of that collective good once provided. This concept is known as the free rider problem.

Consider the example of climate change. Collective action in the form of everyone reducing carbon footprints would yield an abatement of this problem. Yet a single country or an individual has weak incentives. Why?

- A country’s leaders might reason, “If we reduce our carbon emissions through a carbon tax, that might dampen economic growth. Our constituents won’t like that, and that might hurt our global competitiveness.”

- An individual might think, “Let everyone else reduce their consumption, I’ll keep buying lots of stuff, driving cars and taking planes, and eating excessive amounts of animal protein. After all, What difference do my actions make? And if enough of everyone else changes their lifestyles, I can enjoy a healthier planet then, without sacrificing any of my comforts!” This logic is an example of 'free ride', knowing that the benefits of others' work will apply to everyone regardless of their contributions. This problem raises issues of fairness but even worse, a collective good may not be produced if enough people adopt a free-rider mentality.

Collective action also hinges on cooperation, which can be well-illustrated through the so-called Prisoner’s Dilemma. In this scenario, the players cooperate with a partner for mutual reward, or betray their partner for individual reward.

Here's another example of the cooperation game. Imagine Child Y and Child Z have taken cookies from the cookie jar at home -- without asking and while no one was looking. There is enough evidence (the missing cookies) to punish the children for their transgression but not enough proof of a more serious crime (such as repeatedly taking cookies from the cookie jar, over the course of months) to extend their punishment. The interrogating parent pressures each child to offer evidence of the other’s guilt. What should each do?

- Both stay silent--receive the lightest of possible punishments, a week without video games

- One stays silent while the other betrays--the betrayer gets zero punishment while the betrayed receives a long punishment of three weeks without video games.

- Both betray--both aren’t allowed video games for two weeks.

In each box, the first number indicates the punishment for Child Y and the second number indicates the punishment for Child Z (in weeks without video games).

| Payoff: Person Y, Person Z |

Z stays silent |

Z betrays |

| Y stays silent |

-1, -1 |

-3, 0 |

| Y betrays |

0, -3 |

-2, -2 |

This framework illustrates the interdependent nature of the game and weak incentives for cooperation. Each individual sees the immediate personal gain of betrayal. They know that staying silent would be the best for all, but they still have strong incentives to betray because staying silent means putting themselves at risk for the worst possible punishment. The expected outcome is both choosing to betray the other, and both suffering worse outcomes than if they had cooperated with one another.

When playing this game with one hundred or even millions of players, the problems of coordination and cooperation become evident. To take up the example of climate change again, we can replace the choices with the following: staying silent (cooperating) is equivalent to making lifestyle changes to lighten one’s carbon footprint, while betrayal is keeping a heavy carbon footprint. Viewed in this way, individuals’ choices and individual-level outcomes make sense as well as the overall outcome for society. Such cooperation challenges are also evident beyond the individual level. For countries, staying silent is equivalent to a government adopting major climate change mitigation policies, while betrayal is equivalent to doing nothing to address climate change.

Game theorists have developed ways to outsmart the Prisoner's Dilemma. Watch this video to learn more:

Factors promoting collective action

Cooperation can be costly. The Logic of Collective Action highlights important barriers to coordinated action. However, we observe them frequently in the social world.

The free rider problem can be resolved when a group is sufficiently organized. Economist Elinor Ostrom observed the power of smaller groups with unifying interests: “Mobs, gangs, and cartels are forms of collective action as well as neighborhood associations, charities, and voting,” (2009b). His framework suggests that collective action is most likely to take place in groups with concentrated interests, where the effort expended is more likely to yield significant gains for each participant. An example would be the interest groups lobbying in many wealthy democracies today.

Additional organizational factors can encourage collective action, such as the existence of competent leaders or a federated structure where smaller units contribute to a larger whole. It also matters when participants know each other, which raises the level of accountability for any proposed action.

Thomas Schelling has noted that the barriers to collective action are not quite as high as proposed by Olson. In his opinion, collective action is possible when rational and self-interested individuals have reasonable expectations that others will join the movement. This action can happen when individuals signal to each other that they are willing to join the movement. It can be wearing a certain color or seeing a certain number of people subscribed to an organizing website. Hence collective action can often be observed in seemingly sudden moments of rapid change, when everyone is joining the movement because they feel like many others around them are also in the movement.

This framework has its limits because it does not explain who or what is the spark that starts the collective action. Timur Kuran, in the article “Now Out of Never,” suggested individuals are moved to act when they reach their individual threshold for tolerance on an issue. In a collective action situation, there are “first movers” who have the strongest preferences for change. These initial movers then create momentum. For example, people have different tolerances for the effects of climate change. Some individuals want to see change immediately -- and are publicly agitating for those changes or making more quiet personal adjustments -- while others see no need to act. Kuran’s framework is powerful for connecting the individual-level psychology of collective action with what we observe in the streets.

Circling back to the simple cooperation game described above, scholars have also considered the implications of different variations on the game. What might happen if the game is repeated, which is the case for many scenarios in the world, where we see the same people again and again? Kreps et al. have argued convincingly that when a cooperation game such as the Prisoner’s Dilemma is repeated, players will eventually settle on a strategy of cooperation rather than the non-cooperation we observe when the game is played once.

In short, logics exists of collective action. While there exist barriers to collective action, such as group size, the temptation to free ride, and incentives for non-cooperation, there are also conditions under which collective action takes place. Instances of successful collective action can produce desired outcomes such as public goods and sustained stewardship of natural resources. Understanding the conditions under which collective action is possible continues to be critical for organizing the people and resources to address global and community-level challenges which still plague us.

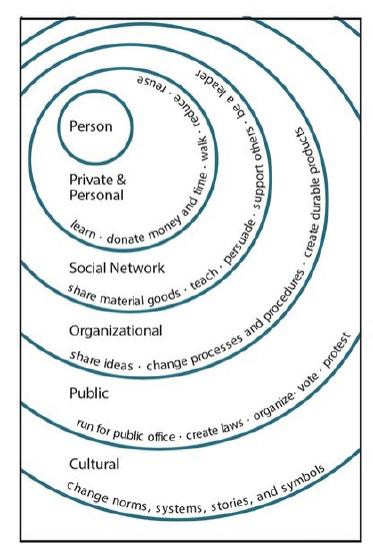

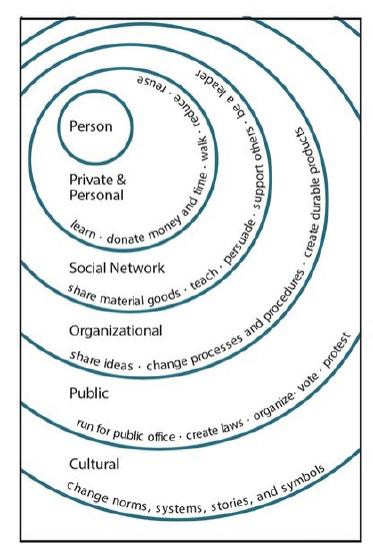

Individuals play a critical role in inspiring collective actions within various spheres of influence. This image was included in the article: Understanding how to inspire individual and collective action on climate change