Introduction

"When is violence considered political?” First, let's define the concept of violence. Kalyvas (2006) states that “[a]t the basic level, violence is the deliberate infliction of harm on people”. While harm can come in many types, such as social or economic oppression, political violence exclusively focuses on physical violence or the use of physical force to exert power. Examples include the use of weapons by criminal gangs to mark their territory, kidnappings, mass shootings, and torture. The simple act of violence itself does not make it political. There is another step. Political violence occurs when the use of physical harm is motivated by political intentions.

Differentiating when an act of violence is criminal or political can be tricky. The drug cartels often target law enforcement, kidnap the loved ones of government officials and threaten the government itself. Thus, by targeting the official capacity of the government, the Mexican drug trafficking groups are politically violent. However, what are the intentions of these narco groups? Their primary interests are financial; the continued flow of narcotics from Central and South America to the U.S. border. Thus, they are not challenging the socio-political order. They have little interest in regime change, or in elections. The drug cartels tend to get involved only when their interests are threatened. As long as the Mexican government stays out of their way, they will respond in kind.

Are interstate wars, or wars between two or more countries, considered political violence? The answer generally is no. The vast majority of political violence transpires within a state. While individuals are being subjugated to political violence in the context of an international war, such a war still is a contestation between two or more sovereign entities. The individuals are “participating” as a member of a sovereign state.

When classifying different forms of political violence, think about who is using the violence. Generally speaking, at least one of the parties is a non-state actor, “an individual or organization that has significant political influence but is not allied to any particular country or state” (Lexico, n.d.). Examples include non-governmental organizations, multinational corporations, and trade unions. Insurgents, guerilla groups, and terrorists may also be considered non-state actors. Finally, political violence can include a wide range of activities: terrorism, assassinations, coups, battles, riots, explosions, and protests.

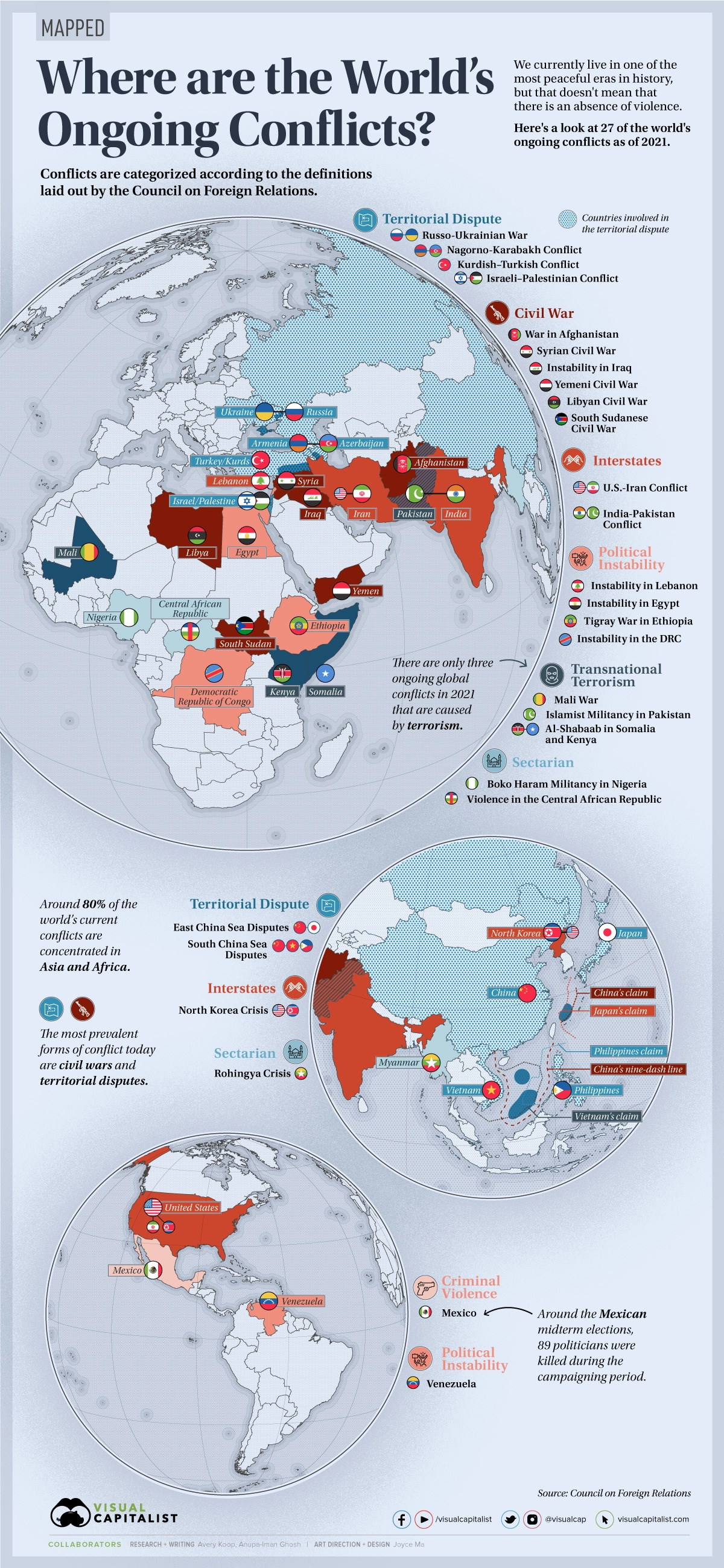

A more difficult differentiation occurs when non-state actors have a transnational presence. Transnational political violence is political violence that occurs across different countries or crosses state borders. By their nature, insurgents and guerilla groups tend not to be transnational, as their focus is on overthrowing a government within a specific country, or succeeding in the secession of a region or province. (Secession is the act of formal withdrawal or separation from a political entity, usually a state. )The goals of secessionist movements are often the creation of a new state, or leaving to join another state.

Since the 1990s, terrorism has become transnational, with the rise of groups such as al-Qaeda, their affiliates, and offspring. These actors blur the line between comparative politics and international relations. As countries have allied to combat transnational terrorist activity, their responses could be understood through international relations theory. In addition, international governmental organizations, such as the United Nations, have also worked with individual member-states on counterterrorism strategies. Still, terrorism is often researched by comparative scholars as the targets of their political violence are civilians. Given that these attacks happen within a country, comparative methodology can help in analyzing and/or assessing terrorist acts and their responses.

Given the above discussion, there are several categories of political violence.

- state-sponsored political violence occurs when a government uses violence either against its own citizens (internal sponsored political violence) or against foreign citizens, usually in neighboring countries (external sponsored political violence)

- non-state sponsored political violence involves insurgencies, civil wars, revolutions, and terrorism