Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Distinguish between economic, political, and social fragmentation.

Introduction

Ironically, while the forces of globalization are strengthening worldwide connections, the forces of fragmentation threaten to tear apart existing global structures. Fracturing can take place at the individual level, the domestic level, and the global level.

The post-Cold War era has seen rapid changes in the way people work, communicate, buy, learn, and in some cases, physically survive. As such, individually, people are becoming less trustworthy of the world around them. Steger and James (2019) called it the Great Unsettling, where earlier ways of acting and knowing have been upended through globalization, causing uneasiness among people. By this, the authors mean relations between “people, machines, regimes, objects, [and] nature” that have defined our lives. An example is the ubiquity of technology and our reliance on it, especially during the pandemic. We use technology to order food, attend classes, and even date. The authors contend that for some people, there is a desire to ‘return’ to the past, when life was simpler.

Domestically, fragmentation is happening in two ways.

- Existing political systems in democratic countries are fraying. Historically, developed or consolidated democracies are dominated by center-right and center-left parties. For many European democracies, this idea was represented by the Christian Democrats on the right and the Social Democrats on the left. Since the Global Financial Crisis (2007-2008) voters have had less faith in established parties.

- Devolution was designed to bring democracy closer to the people through the empowerment of local and regional governments. The goal was to better respond to the voters’ needs, especially in countries with significant ethnic or religious minorities.

Globally, fragmentation is developing in two significant paths.

- The development of economic nationalism usually involves actions taken by a country to protect its economy from outside competition and influences such as tariffs, import quotas, and subsidies.

- Growing geopolitical tension between major powers has occurred. For example, China and Russia see themselves as global powers in their own right and are pushing back against US hegemony. China is asserting itself in the Asia-Pacific region, taking a more nationalistic tone towards the island of Taiwan. Russia has made it clear that the former Soviet Union is its sphere of influence, and has decried the potential NATO membership of neighboring Ukraine.

Economic Fragmentation

Economic fragmentation is intimately linked to globalization. Milanovic’s (2016) study shows that globalization has left many behind. Middle and working-class populations in developed economies have seen little to no benefit. This trend started in the 1990s and accelerated with the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. For example, in the US, the wages of less skilled workers—those without a college education—have stagnated or declined for decades. The pandemic has only made these issues more acute.

Neoliberal economies are deregulated and concentrated in their capital. Thus, Cumbers (2017) suggests that workers in neoliberal economies are ‘economically marginalized’. Workers in countries such as the U.S., UK, Singapore, and other similar countries, suffer from lower levels of social protection, employment rights, and democratic participation in their economic decision-making.

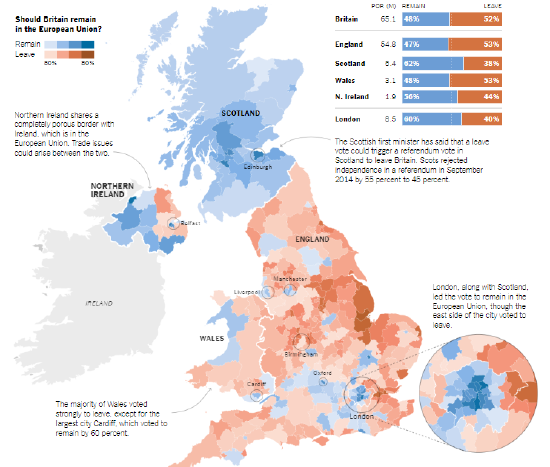

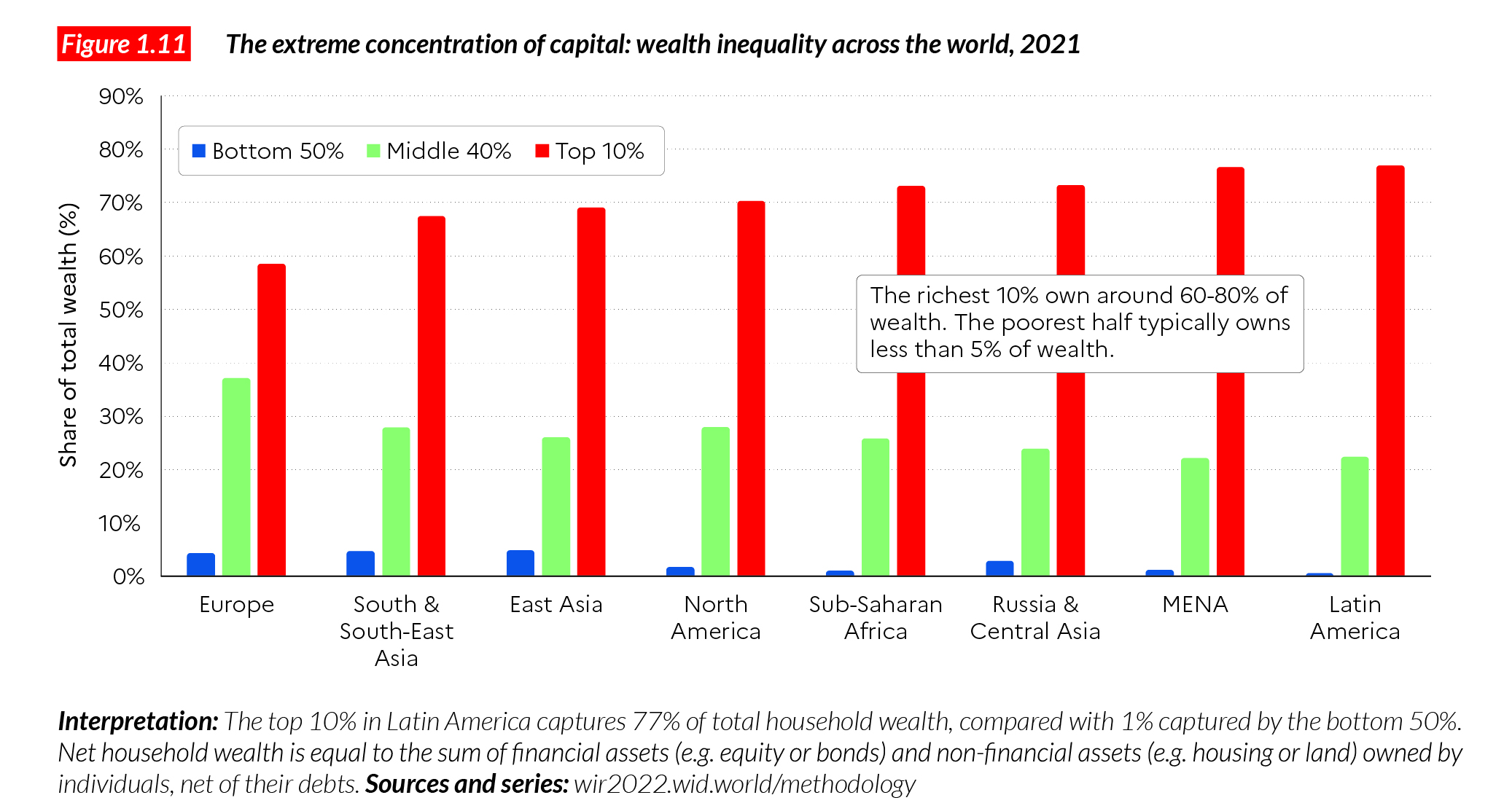

The World Inequality Lab is a research laboratory focusing on the study of inequality worldwide. The WIL hosts the World Inequality Database, the most extensive public database on global inequality dynamics. This image is taken from the World Inequality Report 2022.

The lab breaks the world into regions for comparative studies.

Political Fragmentation

Job losses in manufacturing and other labor positions have a direct effect on domestic politics in democracies, as does the rise of populism, especially national populism. Populism is built on an appeal to the people, is often a denunciation of the elite, and promotes the idea that politics should be an expression of the general will. Ideologically, it can occur on both the left and right sides of the political spectrum.

Leftist populism is characterized by a combination of populism with some form of socialism where the ‘worker’ needs protection from globalization. Its goal is to prioritize class allegiance over national attachment. Leftist populists see capitalists as greedy, and immigration as a weapon used by global capitalists to pit working-class people against each other. Leftist populism had political success in Latin America in the 2000s and is often an alternative.

National populism occurs when right-wing populists combine it with nationalism. In national populism, the ‘nation’ needs protection from globalization. In the aggregate, they oppose or reject liberal globalization, mass immigration, and the consensus politics of recent times. They promise instead to give voice to those who feel that they have been neglected, if not held in contempt, by increasingly distant elites. In addition, they tend to use nationalistic slogans such as “take our country back!” or “make America great again!”

National-Populism centers on three “threats”:

- Threats to one’s employment (economic threat hypothesis)

- Threats to one’s cultural or national identity (cultural threat hypothesis)

- Threats to one’s personal security or physical safety (security threat hypothesis)

Societal Fragmentation

The Global Financial Crisis (2007/2008) exposed serious cracks in global civil society. Belief in the future of globalization was muted, and unemployment levels increased. This event contributed to the Arab Spring, particularly in Egypt, where the crisis affected wages. Similarly, protest movements developed in Greece fueled by the debt crises, and in the US where the Tea Party movement took to the streets.

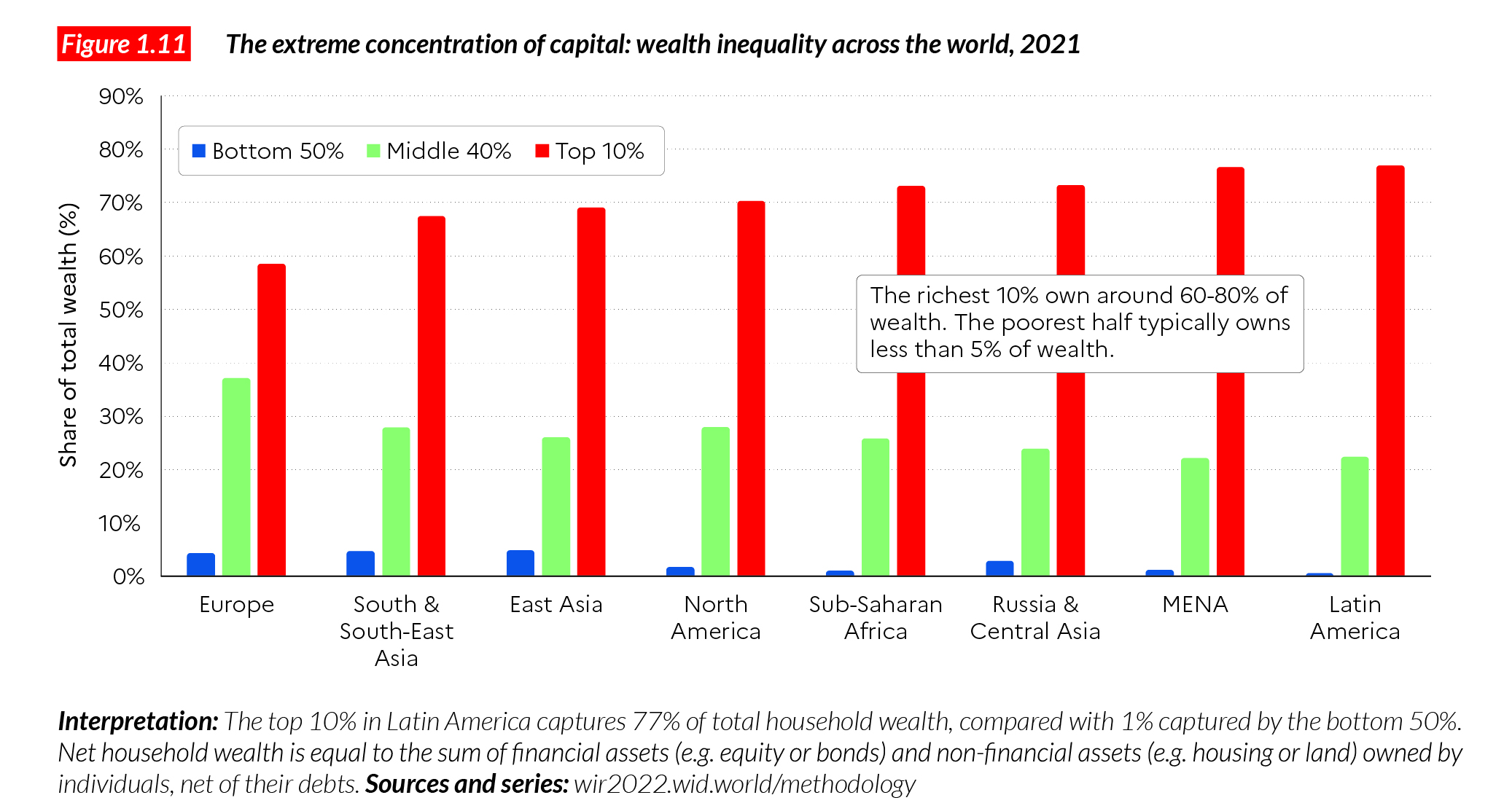

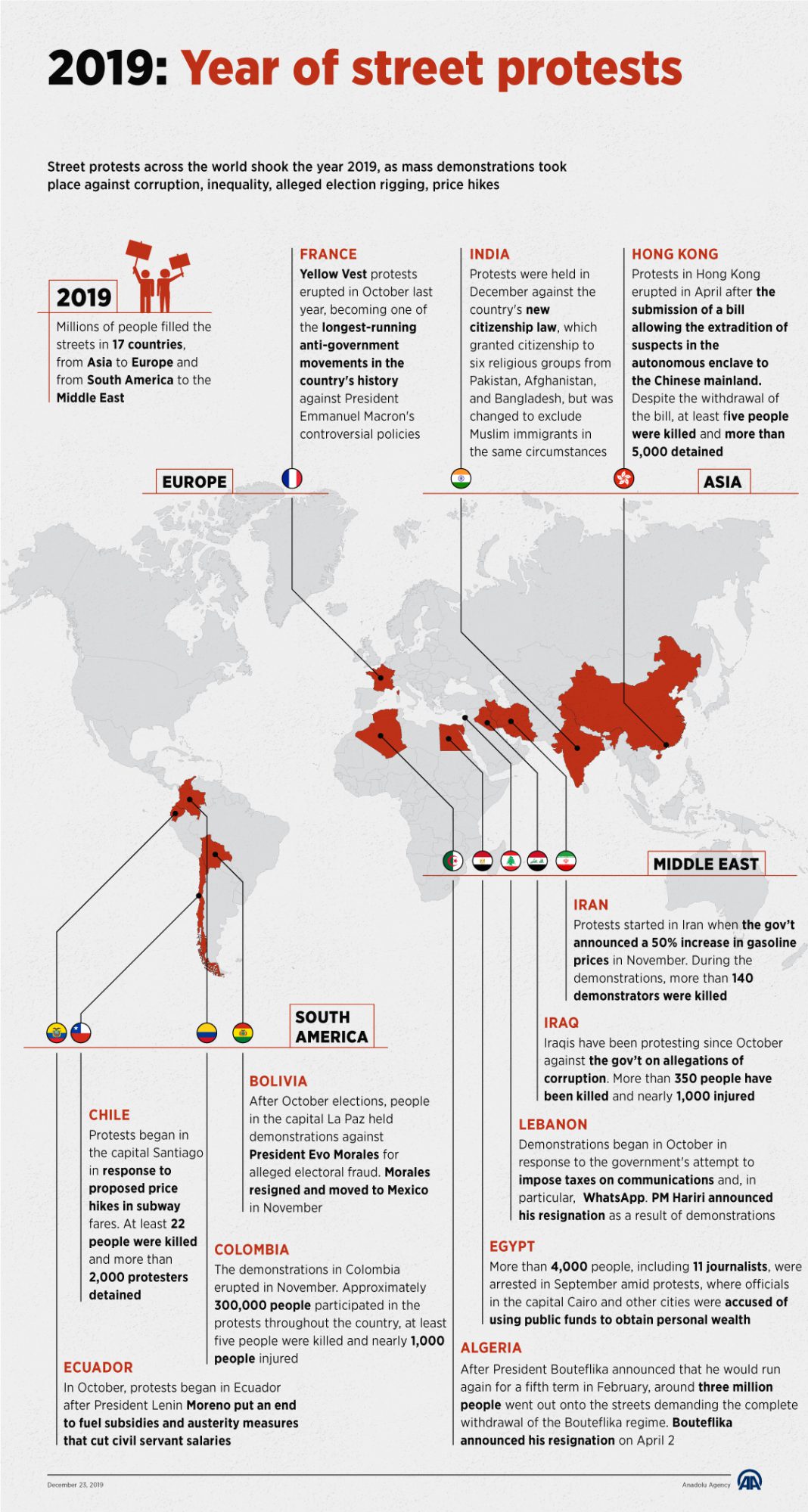

In 2019, the "Year of Protests" occurred. Most of these protests were sparked by local issues, such as rising fuel prices or dissatisfaction with a leader. Others demonstrators shared grievances centered around economic inequality, government corruption, and poor governance. In fact, in Chile, the protests led to a complete rewrite of the country’s constitution.

To see a full-screen image, click here 2019: Year of street protests compiled by the Turkish Press

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to an explosion of protests. According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), protests actually increased 7% in 2020. At first, the protests were against the lockdowns of societies. Then, vaccine mandates led to more protests. Most protesters framed closures and mandates as government overreach and argued they were fighting for their freedoms.

Another example of societal fragmentation is Brexit, the UK’s decision to leave the European Union (EU). The EU is a supranational organization, where member-states agree to give up or share sovereignty on particular issue areas. The UK joined in the 1970s, with the intent of benefiting from closer economic ties. However, as the EU progressively became more of a political union, successive UK governments balked and opted to not enter into three major EU projects:

- the Schengen Agreement, where citizens of the EU can move freely without a passport

- the monetary union, where countries adopted the Euro

- the Charter of Fundamental Rights

Traditionally, the UK has been a global leader in the promotion of neoliberalism. The Global Financial Crisis deeply affected the UK, and the Conservative Party adopted a policy of austerity, where the government preferred not to run large budget deficits to strengthen the economy. General discontent led voters to seek alternative parties. The surge of the UK Independence Party (UKIP) worried the Conservative Party, which forced then Prime Minister David Cameron to call for a Brexit vote so he would not lose MPs to UKIP. UKIP campaigned on an explicit anti-immigrant and anti-Islam message that proved effective. Was UKIP responsible for Brexit? No. But UKIP provided ammunition for people who supported Brexit.

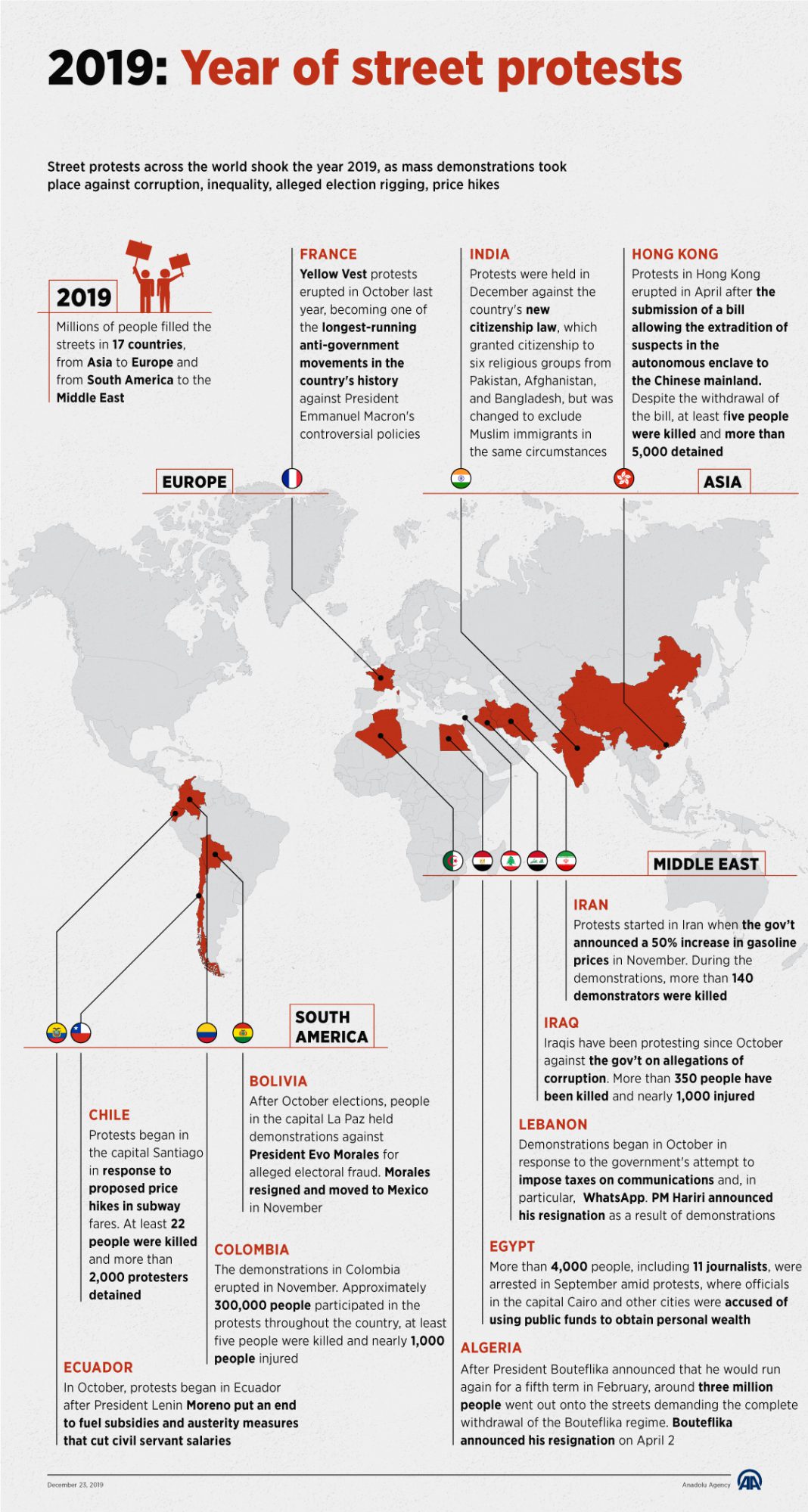

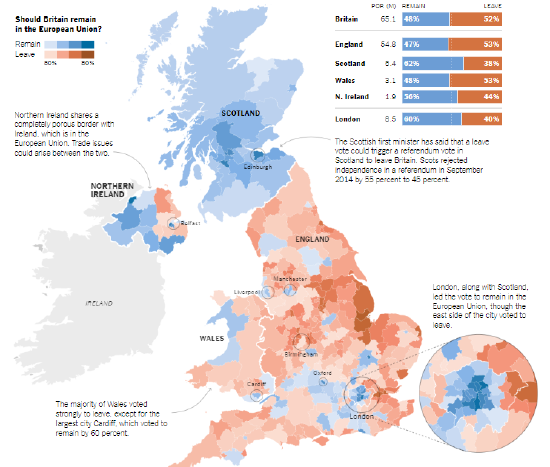

On 23 June 2016, the United Kingdom held a referendum to gauge public support for continued British membership in the European Union, with a majority voting to leave. ‘Sovereignty’ and ‘immigration’ were the two most frequently cited concerns among those who voted Leave. Thus, it was the interaction between Britons’ strong sense of national identity and the enlarged EU’s movement toward a political union that arguably took the UK out.

Brexit has led to serious economic and political consequences. Scotland voted to remain. Indeed, Scottish nationalists are pushing for a second independence referendum, claiming that Brexit goes against the will of the Scottish people. In addition, Brexit has led to a unique situation in Northern Ireland, where the UK shares a land border with Ireland, an EU member-state. To halt the free movement of European citizens into Britain, they would have to erect border controls with the Republic of Ireland or between Northern Ireland and Great Britain. Finally, Brexit has implications for the future of the EU. Could other countries follow? If so, will it become more difficult for Europe to coordinate meaningful policies?

To see a full-screen image, visit How Britain Voted in the E.U. Referendum published by the New York Times