20.5: Russian Revolutions

- Page ID

- 173013

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)At the start of his reign in 1894, at the death of his father Alexander III, Tsar Nicholas II (1868-1918) was among the most powerful monarchs in Europe. Russia may have been technologically and socially backward compared to the rest of Europe, but it commanded an enormous empire and boasted a powerful military. In addition, the Tsars had successfully resisted most of the forces of modernity that had fundamentally changed the political structure of the rest of Europe. Nicholas ruled in much the same manner as had his father, grandfather, and great grandfather before him, holding nearly complete authority over day-to-day politics and the Russian Church.

During his reign, modernity finally caught up with Russia. In the first few years of the 20th Century, the Russian state was able to control the press and punish dissent, but then events outside of its immediate control undermined its ability to exercise complete control over Russian society. The immediate cause of the downfall of Nicholas's royal line, and the entire traditional order of Russian society, was war: The Russo - Japanese War of 1904 - 1905 and, ten years later, World War I.

Japan shocked the world when it handily defeated Russia in the Russo-Japanese War. To many Russians, the Tsar was to blame in both allowing Russia to remain so far behind the rest of the industrialized world economically, and because he had proved to be an indecisive leader. Following the Russian defeat, 100,000 workers tried to present a petition to the Tsar asking for better wages, better prices on food, and the end of official censorship. Troops fired on the unarmed crowds, sparking a nationwide wave of strikes. For months, the nation was rocked by open rebellions in navy bases and cities, and radical terrorist groups managed to seize certain neighborhoods of the major metropolises of St. Petersburg and Moscow. Finally, Nicholas II agreed to allow a representative assembly, the Duma, to meet, and after months of fighting the army managed to regain control.

After the (semi-)revolution, the Tsar still in power, and various newly-constituted political parties were elected to the Duma. Very soon, it was clear that the Duma was not going to serve as a counter-balance to Tsarist power. The Tsar retained control of foreign policy and military affairs. In addition, the parties in the Duma had no experience of actually governing, and quickly fell to infighting and petty squabbles, leaving most actual decision-making to the Tsar and his circle of aristocratic advisors. Still, some things did change: unions were legalized, and the Tsar was not able to completely dismiss the Duma. Most importantly, the state could no longer censor the press effectively. As a result, there was an explosion of anger as various forms of anti-governmental press spread across the country.

One great concern: his only male heir, the prince Alexei, was a hemophiliac (i.e. his blood did not clot properly when he was injured, meaning any minor scrape or cut could be potentially lethal). Nicholas's wife, the Tsarina Alexandra, called upon the services of a wandering, illiterate monk and faith healer named Grigorii Rasputin. Considered one of the most peculiar characters in modern history, Rasputin was somehow able (perhaps through a kind of hypnotism) to stop Alexei's bleeding. Thus, the Tsarina believed God sent him to protect the royal family. Rasputin moved in with the Tsar's family and quickly became a powerful influence.

When World War I began in 1914, the already fragile political balance within the Russian state teetered on the verge of collapse. In the autumn of 1915, as Russian fortunes in the war started to worsen, Nicholas departed for the front to personally command the Russian army. In 1916, a desperate conspiracy of Russian nobles, convinced that Rasputin was the cause of Russia's problems, managed to assassinate him. By then, however, the German armies were steadily pressing toward Russian territory, and tens of thousands of Russian troops were deserting to return to their home villages. As the social and political situation began to approach outright anarchy, one group of Russian communists steeped in the tradition of radical terrorism stood ready to take action: the Bolsheviks.

Radical politics revolved around apocalyptic revolutionary socialism. Mikhail Bakunin was an exemplary figure in this regard. He believed that the only way to create a perfect socialist future was to utterly destroy the existing political and social order, after which "natural" human tendencies of peace and altruism would manifest and create a better society for all. By the late nineteenth century, this homegrown Russian version of socialist theory was joined with Marxism, as various Russian radical thinkers tried to determine how a Marxist revolution might occur in a society that was still largely feudal.

Marx believed a revolution could only happen in an advanced industrial society. The proletariat would recognize that it had "nothing to lose but its chains" and overthrow the bourgeois order. In Russia, however, industrialization was limited to some of the major cities of western Russia, and most of the population were still poor peasants in small villages. This scenario did not look like a promising setting for an industrial working-class revolution.

Enter Vladimir Lenin, an ardent revolutionary and major political thinker. He created the concept of the "vanguard party": a dedicated group of revolutionaries who would lead workers and peasants in a massive uprising. Left to their own devices, he argued, workers alone would always settle for slight improvements in their lives and working conditions (also known as "trade union consciousness") rather than recognizing the need for a full-scale revolutionary change. However, the vanguard party, could both instruct workers and lead to the creation of a new society. A communist revolution could succeed in a backward state like Russia, jumping directly from feudalism to socialism and bypassing industrial capitalism.

In Lenin’s mind, the obvious choice of a vanguard party was his own Russian communist party, the Bolsheviks. By 1917, the Bolsheviks were a highly organized militant group of revolutionaries with contacts in the army, navy, and working classes of the major cities. When political chaos descended on the country as the possibility of full-scale defeat to Germany loomed, the Bolsheviks had their chance to seize power.

In February of 1917, a group of workers in St. Petersburg demonstrated against the Tsar's government to protest the price of food. Within days, similar demonstrations exploded across the country. Then, the army refused to put down the uprisings and instead joined them. Next, the Duma demanded that the Tsar step aside and hand over control of the military. In just a few weeks, the Tsar abdicated, realizing that he had lost the support of almost the entire population.

In the aftermath, power was split. The Duma appointed a provisional government that enacted important legal reforms, but did not have the power to relieve the Russian army at the front or to provide food to the hungry protesters. Likewise, the Duma represented the interests and beliefs of the educated middle classes, a tiny portion of the Russian population. The members of the Duma hoped to create a democratic republic like those of France, Britain, or the United States, but they had no road map to bring it about. Further, it had no way to enforce new laws, nor could it compel Russian peasants to continue fighting the Germans. Most critically, the members refused to sue for peace with Germany, believing that Russia still had to honor its commitment to the war despite the carnage being inflicted on Russian soldiers at the front.

Soon, in the industrial centers and many of the army and naval bases, councils of workers and soldiers (called soviets) sprang up and declared that they had the real right to political power. There was a standoff between the

- provisional government, which had no police force to enforce its will

- soviets, which could control their own areas but did not have the ability to bring the majority of the population (who wanted, in Lenin’s words, “peace, land, and bread”) over to their side.

People fled the cities for the countryside, peasants seized land from landowners, and soldiers deserted in droves. By 1917, fully 75% of the soldiers sent to the front against Germany had deserted.

As of the late summer of 1917, a vacuum had been created by the war and by the incompetence of the Duma. No group had power over the country as a whole, providing an opportunity for the Bolsheviks. In October, the Bolsheviks took control of the most powerful soviet, Petrograd (former St. Petersburg). Next, they seized control of the Duma, expelled the members of other political parties, and then stated their intention to seek unconditional peace with Germany and give land to the peasants with no compensation for landowners. In early 1918, the Bolsheviks signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, granting Germany huge territorial concessions in return for peace. (Germany would lose those new territories when it lost the war itself later that year.)

Almost immediately, a counter-revolution erupted, and civil war broke out. Their “Red Army” (Bolsheviks) engaged the “White” (counter-revolutionaries) all over western Russia and Ukraine. For their part, the Whites were an ungainly coalition of former Tsarists, the liberals who had been alienated by the Bolshevik takeover of the Duma, members of ethnic minorities who wanted political independence, an anarchist peasant army in Ukraine, and troops sent by foreign powers (including the United States), who were terrified of the prospect of a communist revolution in a nation as large and potentially powerful as Russia. Despite the fact that very few Russians were active supporters of communist ideology, the Red Army proved both coherent and effective under Bolshevik leadership.

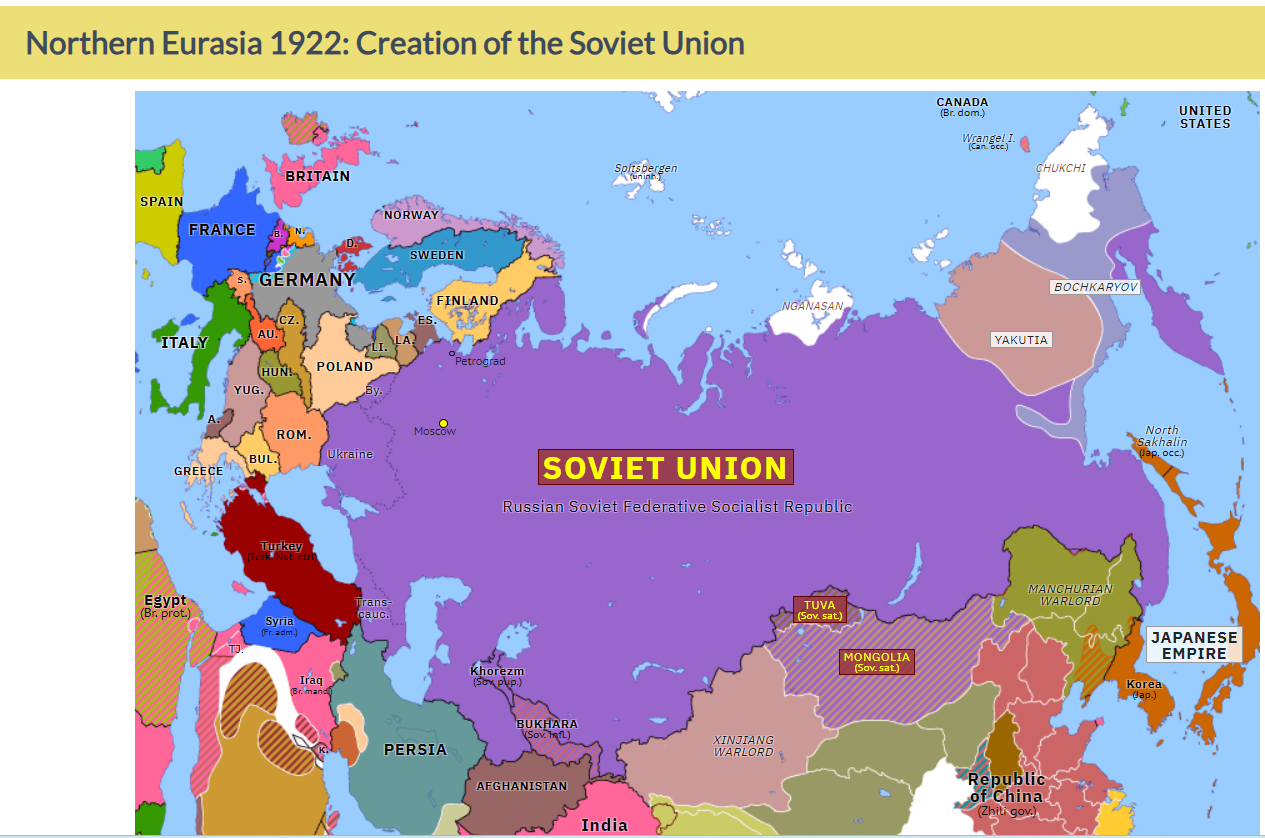

The civil war lasted for four years, and ultimately killed close to ten million people. Most of the causalities were massacred or starved. In the end, the Bolsheviks prevailed. A few Eastern European countries, including Finland and Lithuania, gained their independence. Elsewhere in the former Russian Empire, the Bolsheviks created a new communist empire: the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

Source: Omniatlas