1.1: What is Politics?

- Page ID

- 134518

“Politics is the shadow cast on society by big business.”

–American Philosopher John Dewey (1)

The Definition of Politics

Political scientists study politics in its many forms. At least one professor would say that politics is everywhere. That may be true. If it is, it requires political scientists to cover considerable ground. However, they typically do not concern themselves with things like office politics, family politics, or student-government politics. Generally speaking, political scientists are interested in political matters of consequence at the city, state, national, or international level.

Political scientist Harold D. Lasswell came up with a concise definition of politics that provides a starting point for this course. According to him, politics can be defined as “who gets what, when, and how.” (2)

Who can refer to any member of a polity—a political organization that includes actors such as individuals, groups, corporations, unions, and politicians.

What might refer to government programs, societal resources, access to rights and privileges, or something as banal as tax breaks.

When refers to timing. Often the timing of a thing can be as important as the thing itself. As Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote in his Letter from Birmingham Jail in 1963, “Justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

How are the processes through which someone gets something in a polity, whether it be democratic or undemocratic, open or closed, fair or unfair; or which institutional arrangements are involved, such as constitutions, regulations, and laws; or which practices are employed, such as voting, lobbying, demonstrating, and decision making.

Lasswell’s simple definition of gets is an important word because it implies that someone has to make a choice among competing interests, that resources or benefits have to be allocated, and that the object of politics is limited in some way. After all, if the pie were larger than our combined appetites, we wouldn’t have to struggle over who gets a piece.

Try this definition of politics: Politics is the authoritative and legitimate struggle for limited resources or precious rights and privileges within the context of government, the economy, and society.

For this course, we will concern ourselves with the commonly understood practice of authoritatively and legitimately allocating resources—i.e., of who gets what. Of course, these are loaded terms, because one person’s view of authoritative and legitimate struggles over allocating resources might be different from another’s view. What we mean here is that regularized, established, legal, and generally accepted procedures are employed in allocating resources. If I work through the system and get more resources than you, it’s politics. If I steal something from you, it’s not politics.

We also want to highlight the word struggle. Politics in the United States is often a chaotic and painful clash of entrenched interests. Sometimes, a reasonable accommodation can be reached that satisfies all, but often the solution grossly favors one set of interests over others. As we’ll see—and as hinted at in John Dewey’s quote above—the struggle is often an unfair one, as those with the most resources and the most persistence have clear advantages in getting what they want out of the political system.

Government is a prime location for political struggles. Government refers to the collection of institutions and people who occupy them that is recognized as the legitimate authority to make decisions regarding the whole public in a defined geographic territory. An institution is an established organization, custom, or practice formed for a specific public purpose. Governments are composed of institutions like legislatures, courts, bureaucratic offices, and the like. Other institutions like civil marriage or corporations exist because government establishes rules and practices by which they operate.

Our definition broadens the traditional scope of politics to include the economy and society. Politics exists outside of legislative votes, Supreme Court nominations, and the voting behavior of citizens. These other contexts are important considerations. For example, how have historical developments preconditioned certain outcomes in today’s political world? Are economic and social considerations such as race, gender, and class relevant in allocating resources or accessing rights and privileges? Should people have a say in all major decisions that affect them? At work? In school? In church? If people do not have the ability to be full-fledged political actors in those settings, what impact would that have on their behavior and approach to traditional political campaigns, legislative debates, political news, and elections?

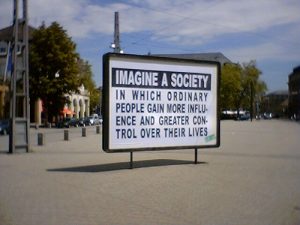

Political Imagination

Throughout this course, you should exercise your political imagination. In other words, ask “What if” questions: What if being informed about political issues and being registered to vote were a high school graduation requirement? What if we got rid of the nomination process and chose our candidates by lottery instead of primaries and caucuses? (Selecting decision-makers by lottery is an idea as old as the ancient Greeks.) What if every person were given an equal amount of money by the government each year to donate to a political cause and that money was the only money allowed to be spent on politics? What if we required that four of the nine Supreme Court justices could not possess a law degree?

Asking these kinds of questions gets us into two habits:

1) Envisioning a different and potentially better future

2) Realizing that our future is up to us.

All the good things in our country (national parks, public libraries, and public transportation)—and all the negative things (homelessness, suburban sprawl, and payday loan sharks)—are the result of political decisions that our polity made sometime in the past. We don’t have to accept our predecessors’ bad political decisions. We can make new, hopefully, better decisions. It just takes imagination, organization, and action.

A Word About Terminology

The term "American" has different meanings in different parts of the world. Throughout this course, we have tried to use the United States or U.S., as much as possible.

References

- John Dewey, The Later Works of John Dewey, 1925 – 1953. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press,2008. Page 163.

- Harold D. Lasswell, Politics: Who Gets What, When, and How. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1938.

Media Attributions

- Imagine © Fred is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license