7.6: The Historical Development of the News Media

- Page ID

- 134570

"The media . . . tend to ignore broad social and economic policy issues because their complexity makes it difficult to simplify and dramatize them.”

—William Hudson (1)

The mass media provides information and images that range from the ridiculous to the sublime. Entertainment has political ramifications. Indeed, the entertainment industry can be overtly political while also covertly reinforcing or challenging established social and political norms and myths. For this page, the term media refers to mass communication’s whole range, involving newspapers, books, radio, television, movies, recorded music, and the internet. News media reflects mass communication’s subset news forms, which impart useful information that citizens need in a democratic republic.

A Quick History of the Media in U.S. Politics

From the beginning, the news media has been intimately involved in the U.S. political process. John Peter Zenger began publishing the New York Weekly Journal in 1733, and almost immediately printed critical articles about New York colony governor William Cosby, accusing him of “schemes of general oppression and pillage, schemes to depreciate or evade the laws, restraints upon liberty and projects for arbitrary will.” The paper went on to say that Cosby’s rule was so corrupt that the people of New York might soon rise up against the government. Zenger was arrested in 1734 and tried for seditious libel. The jury found him not guilty because the critical stories were factual and so did not constitute libel. Andrew Hamilton, Zenger’s lawyer, told the jury that “every man, who prefers freedom to a life of slavery, will bless and honor you, as men who have baffled the attempt of tyranny…exposing and opposing arbitrary power in these parts of the world at least, by speaking and writing truth.” (2) The case encouraged a rowdy press in the American colonies and also dissuaded the British from prosecuting writers who criticized them in the run-up to the American Revolution.

At the Constitutional Convention, the delegates adopted a secrecy rule. When someone carelessly left a copy of the Virginia Plan outside the meeting chamber, George Washington rose to “entreat the gentlemen to be more careful, least our transactions get into the newspapers and disturb the public repose by premature speculations.” (3) At the time of the American Revolution and the Constitutional Convention, the United States possessed a broadly literate population of white men who, for the most part, were able to read the arguments over independence and the debates between the federalists and the anti-federalists published in newspapers, journals, pamphlets, and flyers.

In 1798, Congress passed, and President Adams signed the Sedition Act, generally considered to be one of the greatest threats to a free press in the United States. Basically, the Federalist politicians were attempting to stifle the voices of opposition newspapers.

That if any person shall write, print, utter or publish…or shall knowingly assist or aid in writing, printing, uttering, or publishing any false scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of Congress of the United States, or the President of the United States, with intent to defame the said government, or to bring them…into contempt or disrepute; or to excite against them…the hatred of the good people of the United States, or to stir up sedition within the United States, or to excite any unlawful combinations therein, for opposing or resisting any law of the United States…then such person, being thereof convicted before any court of the United States having jurisdiction thereof, shall be punished by a fine not exceeding two thousand dollars, and by imprisonment not exceeding two years. (4)

The law did not exactly spell out how one would go about establishing the truth of an unfavorable opinion. Twenty-five Americans were arrested under the Sedition Act. Of which, fifteen were indicted for trial. The Sedition Act expired the day before President Jefferson took office in 1801, and Jefferson pardoned those who had been convicted under the law. Jefferson went on to bring seditious libel charges against Harry Croswell, a Federalist newspaper editor. Again, the case hinged on whether Croswell had printed the truth when he alleged that Jefferson paid James Callender to slander George Washington, John Adams, and other Federalists. Croswell was initially convicted of seditious libel but was granted a new trial after New York changed its libel laws. He was acquitted in the second trial, but no definitive evidence established the truth of his claims. (5)

During the latter half of the nineteenth century that the number of daily newspapers exploded from approximately 250 to over 2,000. The increase was partly due to the colonization of the American West and the creation of towns and cities that needed their own newspapers. Technology also improved and made it easier to print large runs of a newspaper in one day and then turn around and do it again the next day. Prices decreased as well.

After Benjamin Day began the first penny press in New York in 1833, more inexpensive newspapers proliferated. The 19th Century was the golden era of the partisan press. Most newspapers didn’t worry about objectively printing the day’s or week’s events. Indeed, they were often openly tied to political parties or movements and tilted the news accordingly. Competition in the business was stiff, and publishers often went for scandal and sensationalism to sell newspapers. This yellow journalism was perfected through the rivalry of the New York World, published by Joseph Pulitzer, and the New York Journal, published by William Randolph Hearst. Both Hearst and Pulitzer stirred up stories of Spanish atrocities in Cuba and implicated Spain in the explosion that destroyed the U.S.S. Maine in Havana harbor, which swayed the people to support the Spanish-American War.

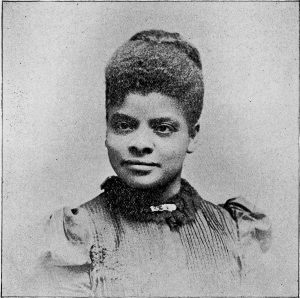

The early 20th Century muckrakers were pioneers of investigative journalism that continues to challenge the politically and economically powerful. (6) Considered a badge of honor among investigative journalists, a muckraker is a progressive-minded writer who investigates and reports on abuses of power and on the ways that government serves powerful interests at ordinary people’s expense. Lincoln Steffens was an editor and writer for McClure’s Magazine, where he wrote a series of investigative reports called “The Shame of the Cities” and “The Shame of the States,” focusing on political corruption and efforts to fight it. Ida Tarbell investigated the Standard Oil Trust, exposing the secret bookkeeping, bribery, sabotage, conspiracy and other machinations of the monopoly. Upton Sinclair wrote, The Jungle, which described the life of meatpacking industry workers through the character of Jurgis Rudkos and his family, as they experience corruption, injury on the job, unsanitary work conditions, jail, and homelessness. The publication of The Jungle aided the movement to pass the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. David Graham Phillips wrote a nine-installment series called “Treason of the Senate” in 1906, which documented corporate manipulation and the corrupt process of selecting U.S. Senators, which galvanized the reform movement that eventually resulted in the Seventeenth Amendment (1913) mandating that senators be elected directly by the people. Ida B. Wells, who was born into slavery and become a journalist and a African-American and women’s rights crusade organizer, wrote the pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, in which she referred to lynching as “that last relic of barbarism and slavery.”

By the 1920s, newspapers had a competitor. Radio was becoming commonplace, having an immediacy and presence that newspapers couldn’t replicate. Politicians could speak directly to people, unmediated by journalists and newspaper editors. The most effective early use of radio was Franklin Roosevelt’s “fireside chats” that began in 1933 and ran to 1944. These broadcasts helped him explain his policies and decisions directly to millions. For example, in the December 9, 1941 fireside chat he said,

“We are now in this war. We are all in it—all the way. Every single man, woman, and child is a partner in the most tremendous undertaking of our American history. We must share together the bad news and the good news, the defeats and the victories—the changing fortunes of the war.” (7)

In 1982, President Reagan revived the practice of doing a weekly radio broadcast, and presidents George Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama continued to do so. President Trump initially started doing weekly broadcasts on YouTube, but then stopped the practice.

The early 20th Century also witnessed the rise of a journalistic culture of objectivity. The partisan press of the nineteenth century began to fade, and professional journalism schools graduated journalists committed to reporting the news without intentionally slanting their coverage to suit party politics or ideology. Newspaper pages began to be separated into news stories, editorials, columns, and letters to the editor. The news stories were supposed to be objective, while the others were free to express opinions that would come from the author’s partisan or ideological preferences. The culture of objectivity continues to characterize most mainstream media outlets. Generally speaking, this is a positive aspect of American journalism. However, critics have pointed out that the culture of objectivity has unfortunately led to a false balance on some issues. False balance has been defined as “when journalists present opposing viewpoints as being more equal than the evidence allows. But when the evidence for a position is virtually incontrovertible, it is profoundly mistaken to treat a conflicting view as equal and opposite by default.” (8) According to these critics, both sides of issues like climate change and the efficacy of vaccines are treated equally in the media, when the science is overwhelmingly one-sided.

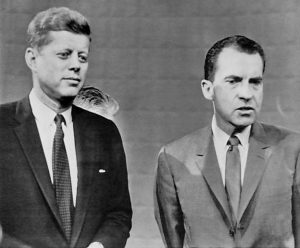

In the 1950s, the emergence of television eroded the preeminence of both radio and newspapers. Political campaigns started marketing candidates in television commercials that became increasingly more sophisticated over time. Televised presidential debates began in the 1960 election, and it immediately became clear that a candidate benefited from being telegenic. In the first of the four Nixon-Kennedy presidential debates in 1960, radio listeners thought that Nixon bested Kennedy, while television viewers came to the opposite conclusion. The reason? The radio listeners couldn’t see that with no make-up and sporting a five o’clock shadow, Nixon looked horrible compared to the tanned, make-up-wearing Kennedy. No presidential candidate has ever made Nixon’s mistake again. (9)

From 1949 to 1987, communication on public airwaves like radio and television was governed by the fairness doctrine. The Federal Communications Commission required licensees to serve the public interest in two ways:

- devote a “reasonable percentage of their broadcasting time to the discussion of public issues of interest to the community served by their stations”

- design programs “so that the public has a reasonable opportunity to hear different opposing positions on the public issues of interest and importance in the community.” (10)

Conservatives campaigned against the fairness doctrine, and Republican-appointed FCC commissioners voted to end it in 1987 even though congressional Democrats objected. Scrapping the fairness doctrine helped give rise to the resurgence of partisan media in the United States. This action, in turn, has contributed to the polarizing of the people.

The most recent development in political media’s history is the rise of the partisan conservative media ecosystem. The demise of the fairness doctrine in 1987 allowed corporations and wealthy libertarians to develop an especially insular media empire centered on conspiracy theories and partisan news. The Columbia Journalism Review explains the conservative media ecosystem’s meteoric rise after Republicans junked the fairness doctrine:

“A remarkable feature of the right-wing media ecosystem is how new it is. Out of all the outlets favored by Trump followers, only the New York Post existed when Ronald Reagan was elected president in 1980. By the election of Bill Clinton in 1992, only the Washington Times, Rush Limbaugh, and arguably Sean Hannity had joined the fray. Alex Jones of Infowars started his first outlet on the radio in 1996. Fox News was not founded until 1996. Breitbart was founded in 2007, and most of the other major nodes in the right-wing media system were created even later.” (12)

This media ecosystem predominantly exists outside of traditional journalistic outlets. It operates with its own journalistic standards and draws stories from the conspiratorial fringes to the more prominent outlets like Fox News, which is owned by the Australian billionaire Murdoch family. Often immune from facts, this media ecosystem recycles conspiracy theories: climate change is a Chinese hoax; prominent Democrats were running a child pornography ring out of a pizza restaurant in Washington; Ukraine was behind the theft of Democratic emails, and the server in question was hidden somewhere in that country; millions of illegal immigrants regularly voted in recent American elections; Barack Obama’s birth certificate was forged, and he wasn’t really born in Hawaii; a Democratic National Committee staffer stole the Democratic emails in 2016—not the Russians, as U.S. intelligence agencies concluded—and then was murdered for it, and so on. (13) This conservative media ecosystem's alternate reality empowers and normalizes what, in the past, were ideas that only existed at the fringes of U.S. political culture.

References

- William E. Hudson, American Democracy in Peril. Eight Challenges to America’s Future. Sixth edition. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2010. Page 194.

- Eric Burns, Infamous Scribblers. The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism. New York: Public Affairs, 2006. Pages 102-111.

- Christopher Collier and James Lincoln Collier, Decision in Philadelphia. New York: Ballantine Books, 1986. Page 115.

- Eric Burns, Infamous Scribblers. Pages 355-356.

- John Dickerson, “The Original Attack Dog,” Slate. August 9, 2016. The People of the State of New York v. Harry Croswell (1804).

- This section relies on Ann Bausum, Muckrakers. How Ida Tarbell, Upton Sinclair, and Lincoln Steffens Helped Expose Scandal, Inspire Reform, and Invent Investigative Journalism. Washington: National Geographic. 2007.

- The fireside chats are available from the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum.

- David Robert Grimes, “Impartial Journalism is Laudable. But False Balance in Dangerous,” The Guardian. November 8, 2016.

- To be fair, Nixon had recently injured his knee and spent two weeks in the hospital. He was still reportedly weak and twenty pounds underweight the night of that debate.

- William B. Fisch, “Plurality of Political Opinion and the Concentration of Media in the United States,” The American Journal of Comparative Law. Volume 58, 2010. Page 514.

- Lawrence Lessig, They Don’t Represent Us: Reclaiming Our Democracy. New York: HarperCollins. Page 94.

- Yochai Benkler, Robert Faris, Hal Roberts, and Ethan Zuckerman, “Breitbart-led Right-Wing Media Ecosystem Altered Broader Media Agenda,” Columbia Journalism Review. March 3, 2017.

- David Atkins, “The Conspiracy Theories a Conservative Must Believe Today,” Washington Monthly. November 10, 2019. David Roberts, “Why Conspiracy Theories Flourish on the Right,” Vox. September 13, 2016. Oliver Darcy, “Fox News Staffers ‘Disgusted’ at Network’s Promotion of Seth Rich Conspiracy Theory,” CNN Business. May 22, 2017.

Media Attributions

- Wells © Lawson Andrew Scruggs is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Kennedy Nixon © Associate Press is licensed under a Public Domain license