9.5: Campaign Finance

- Page ID

- 134578

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)“Money, get back

I’m all right, Jack, keep your hands off of my stack

Money, it’s a hit

Don’t give me that do goody good bullshit

I’m in the high-fidelity first-class traveling set

And I think I need a Learjet”

—Pink Floyd (1)

“The concentration of wealth in America has created an education system in which the super-rich can buy admission to college for their children, a political system in which they can buy Congress and the presidency, a health-care system in which they can buy care that others can’t, and a justice system in which they can buy their way out of jail.”

—Robert Reich (2)

The Role of Money in U.S. Politics

Money is so central to politics that political scientists and journalists often speak about the money primary, by which they mean “the competition of candidates for financial resources contributed by partisan elites before the primaries begin.” (3) You must either have enough to finance your own campaign, come from the elite strata where you have friends, contacts, and supporters with disposable wealth to donate to your campaign, or you must ingratiate yourself to the elites who can fund your campaign.

Because elections are so expensive, politicians appear to be in a never-ending race for money. It typically takes million dollars to win a race for House of Representatives or Senate. In presidential races, the candidates together spend billions of dollars—not counting outside spending by organized interests on behalf of one candidate or the other. (4) Congressional members can easily spend half their working time raising money rather than legislating. According to Newsweek, “A leaked PowerPoint presentation from the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) revealed that an ideal daily schedule consists of four hours of time spent on the phone.” (5) The need for money has even changed the very nature of congressional leadership. As law professor Lawrence Lessig said, “If leaders had once been chosen on the basis of ideas, or seniority, or political ties, now, in both parties, leaders were chosen at least in part on their ability to raise campaign cash. Leading fundraisers became the new leaders. Fundraising became the new game.” (6)

Corporations and wealthy individuals contribute the bulk at least two-thirds of federal-election money. A 2010 Good Magazine analysis revealed that .26 percent of the American population made up 68 percent of the money contributed to congressional members. (7) Former U.S. Secretary of Labor Robert Reich reported that while in 1980 the richest .01 percent of Americans accounted for 15 percent of all campaign contributions, by 2016 the richest .01 percent of Americans accounted for 40 percent of all campaign contributions. (8) Some candidates such as Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren did a good job crowd-sourcing their campaigns with large numbers of small donors, but they lost to other candidates in 2016 and 2018.

The candidate who spends the most money tends to win. Historically, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, the better financed House candidate wins about 90 percent of the time and the better financed Senate candidate wins about 80 percent of the time. (10) Most congressional races are financially uncompetitive, meaning that one candidate is spending two or more times the money of the other candidate.

Money pushes politics in a conservative direction. Back in 1995, political scientist Thomas Ferguson coined the phrase the investment approach to American party politics, in which he argued that ordinary voters cannot afford the costs of paying attention to political issues, researching candidates, watching what they do once elected, and rewarding or punishing them if they don’t pursue policies beneficial to those ordinary people. Who can afford those costs? Corporations and the wealthy invest in politics in ways that ordinary people cannot match, which pulls the entire system to the Right or conservative side of the ideological spectrum. (11)

The Supreme Court has stricken down many attempts to reign in money in American elections.

- Buckley v. Valeo (1976) Overall campaign spending, personal spending on one’s own campaign, and independent expenditures cannot be capped.

- FEC v. Wisconsin Right to Life (2007) The government cannot stop outside groups from spending on political advertising in the period before an election.

- Citizens United v. FEC (2010) The government cannot place limits on the amount of outside spending, and corporations can spend directly to support or oppose campaigns.

- Arizona’s Free Enterprise Club’s Freedom PAC v. Bennett (2011) Public financing systems cannot use escalating matching funds.

- American Tradition Partnership v. Bullock (2012) The Court struck down Montana’s ban on corporate spending on state elections that dated back to 1912.

- McCutcheon v. FEC (2014) A donor’s overall spending on federal campaigns cannot be capped. (12)

The Federal Election Commission (FEC), charged with regulating America’s election and campaign finance laws, has long been referred to as “The little agency that can’t.” (13) Structurally, the nature of the commission produces deadlock because the Democrats and Republicans each have the same number of commissioners. The FEC is under-funded, under-staffed, and has a perpetual backlog of cases so that candidates and organized interests have little fear of being prosecuted for alleged violations. (14) Sometimes, the FEC is given a near impossible task. Take the case of coordination: outside groups are forbidden from coordinating their expenditures with political campaigns. It’s extremely difficult to prove, especially for a hobbled agency like the FEC. (15)

Attempting to Regulate Money in U.S. Elections

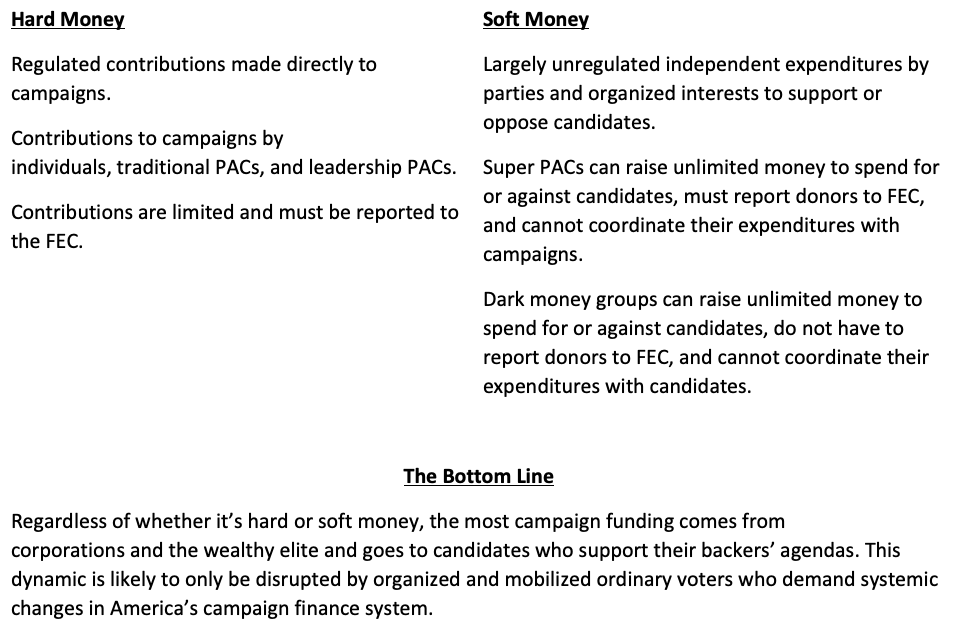

The U.S. has a long history of trying to regulate money in politics. The Tillman Act of 1907 banned corporations from making direct campaign contributions, and this prohibition was extended to unions in 1943. In 1971, Congress passed the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA). Over time, laws and court decisions have created a fairly confusing medley of rules and allowances. Generally speaking, we divide campaign finance into hard money and soft money.

Political Action Committee (PAC)

A political action committee, or PAC, is an FEC-recognized entity that can legally engage in campaign finance. There are different types of PACs that give directly to campaigns

- Traditional PACs are entities created by organized interests—corporations, unions, and interest groups—as vehicles to raise money and funnel it to candidates.

- Leadership PAC is established or controlled by a political candidate or a person who holds federal office to raise and give money to other politicians. Leadership PACs are separate from the candidate or office holder’s election or reelection committee. Congressional members often have leadership PACs to raise money and support candidates or other congressional members with whom they share ideology, party affiliation, or policy positions.

PACs give the overwhelming majority of their money to incumbents, or those who are in office and are running for reelection, as opposed to challengers. There are three reasons why PACs favor incumbents. For one thing, incumbents tend to win. Second, incumbents have Washington experience and might sit on important committees. Finally, incumbents have a voting track record on national issues.

Super PACs are a new kind of organization that falls under the soft money category. Where traditional and leadership PACs donate money directly to campaigns, super PACs cannot do so. But they can spend unlimited amounts of money on behalf of one candidate or another. However, they must act independently of the candidate they are supporting, meaning they cannot coordinate their activities with the candidate's campaign. They can also raise unlimited amounts of money from corporations, unions, and individuals, but they must disclose their donors to the FEC.

A special kind of soft money is called dark money. Under sections 501(c)(4) and 501(c)(6) of the tax code, politically active nonprofit organizations can raise unlimited money and spend it to support or oppose candidates. “Dark” means that they don’t have to disclose the sources of their money. These organizations are supposed to be primarily social-welfare groups rather than overtly political, but neither the IRS nor the FEC has cracked down on them.

What If. . . ?

What if in every election cycle, the federal government gave all voting age adults four “democracy vouchers” of $10 each that they could donate to any federal campaign or donate to no one? What if candidates for federal office could decide whether to raise money from corporations, wealthy individuals and PACs, or they could raise money via these democracy vouchers, but not both? (19)

References

- “Money” written by Roger Waters of Pink Floyd.

- Robert B. Reich, The System: Who Rigged It, How We Fix It. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2020. Kindle edition. Page 4 of 198.

- Randall E. Adkins and Andrew J. Dowdle, “The Money Primary: What Influences the Outcome of Pre-Primary Presidential Nomination Fundraising?” Presidential Studies Quarterly. June, 2002. Page 257.

- See current figures at Center for Responsive Politics website: www.opensecrets.org

- Stacey Selleck, “Congress Spends More Time Dialing for Dollars Than on Legislative Work,” U.S. Term Limits. April 26, 2016. Ryan Bort, “John Oliver Breaks Down the Disturbing Truth of Congressional Fundraising.” Newsweek. April 4, 2016.

- Lawrence Lessig, Republic, Lost: How Money Corrupts Congress—and a Plan to Stop It. New York: Twelve, 2011. Page 94.

- See current figures at Center for Responsive Politics website: www.opensecrets.org. See the Good Magazine infographic here.

- Robert B. Reich, The System: Who Rigged It, How We Fix It. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2020. Kindle edition. Page 16 of 198.

- Peter Overby, “Explainer: What is a Bundler?” NPR. September 14, 2007. Maggie Severns, “Biden Reveals Deep Bench of Campaign Bundlers,” Politico. December 27, 2019.

- Anonymous Author, “Did Money Win?” Center for Responsive Politics.

- Thomas Ferguson, Golden Rule: The Investment Theory of Party Competition and the Logic of Money Driven Political Systems. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1995. See his quick synopsis of this theory on YouTube.

- Andrew Prokop, “40 Charts That Explain Money in Politics,” Vox. July 30, 2014.

- Benjamin Weiser and Bill McAllister, “The Little Agency That Can’t,” The Washington Post. February 12, 1997.

- Dave Levinthal, “Another Massive Problem With U.S. Democracy: The FEC is Broken,” The Atlantic. December 17, 2013. Kelly Ceballos, “Federal Election Commission Must Be Restructured,” League of Women Voters. April 14, 2016. Soo Rin Kim, “FEC Left Toothless With Three Empty Seats Heading Into the 2020,” ABC News. August 27, 2019.

- Rachael Marcus and John Dunbar, “Rules Against Coordination Between Super PACs, Candidates, Tough to Enforce,” Center for Public Integrity. January 13, 2012.16. Center for Responsive Politics. At https://www.opensecrets.org/outsidespending/fes_summ.php

- See current figures at Center for Responsive Politics website: https://www.opensecrets.org/dark-money/top-election-spenders

- Lawrence Lessig, Republic, Lost: How Money Corrupts Congress—and a Plan to Stop It. New York: Twelve, 2011. Page 191.

- Lawrence Lessig, They Don’t Represent Us: Reclaiming Our Democracy. New York: Harper Collins, 2019. Pages 141-142.

Media Attributions

- Money Politics © Damian Gadal is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Campaign Finance Summary © David Hubert is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license