10.4: Defining Foreign Policy

- Page ID

- 147681

NOTE: Domestic Policy (also known as Public Policy) sets strategies internal to the United States, and was discussed in a previous chapter.

Foreign Policy Basics

What is foreign policy? One definition could be “the goals that a state’s officials seek to attain abroad, the values that give rise to those objectives, and the means or instruments used to pursue them.” [1] Foreign policy can be intertwined with domestic policy. For example, one might talk about Latino politics as a domestic issue when considering educational policies designed to increase the number of Hispanic Americans who attend and graduate from a U.S. college or university.[2] However, as demonstrated in the primary debates leading up to the 2016 election, Latino politics can quickly become a foreign policy matter when considering topics such as immigration from and foreign trade with countries in Central America and South America.[3]

What are the objectives of U.S. foreign policy? While the goals of a nation’s foreign policy are always open to debate and revision, there are nonetheless four general ideas:

- The protection of the U.S. and its citizens both while they are in the United States and when they travel aboard--Related to this security goal is the aim of protecting the country’s allies, or countries with which the United States is friendly and mutually supportive. In the international sphere, threats and dangers can take several forms, including military threats from other nations or terrorist groups and economic threats from boycotts and high tariffs on trade.

- The maintenance of access to key resources and markets--Resources include natural resources, such as oil, and economic resources, including the infusion of foreign capital investment for U.S. domestic infrastructure projects like buildings, bridges, and weapons systems. Of course, access to the international marketplace also means access to goods that American consumers might want, such as Swiss chocolate and Australian wine. U.S. foreign policy also seeks to advance the interests of U.S. business, to both sell domestic products in the international marketplace and support general economic development around the globe (especially in developing countries).

- The preservation of a balance of power in the world--A balance of power means no one nation or region is much more powerful militarily than the countries of the rest of the world. The achievement of a perfect balance of power is probably not possible, but general stability, or predictability in the operation of governments, strong institutions, and the absence of violence within and between nations may be.

- The protection of human rights and democracy--While certainly looking out for its own strategic interests in considering foreign policy strategy, the United States nonetheless attempts to support international peace through many aspects of its foreign policy, such as foreign aid, and through its support of and participation in international organizations such as the United Nations, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the Organization of American States. support of and participation in international organizations such as the United Nations, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the Organization of American States.

International Organizations

The United Nations (UN) is perhaps the foremost international organization in the world today,. The General Assembly includes all member nations and admits new members and approves the UN budget by a two-thirds majority. The Security Council includes fifteen countries, five of which are permanent members (including the United States) and ten that are non-permanent and rotate on a five two-year-term basis. The entire membership is bound by the decisions of the Security Council, which makes all decisions related to international peace and security. Two other important units of the UN are the International Court of Justice in The Hague (Netherlands) and the UN Secretariat, which includes the Secretary-General of the UN and the UN staff directors and employees. The UN’s main purposes are to maintain peace and security, promote human rights and social progress, and develop friendly relationships among nations.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was formed after World War II as the Cold War between East and West started to emerge. While more militaristic in approach than the United Nations, NATO has the goal of protecting the interests of Europe and the West and the assurance of support and defense from partner nations. However, while it is a strong military coalition, it has not sought to expand and take over other countries. Rather, the peace and stability of Europe are its main goals. NATO initially included only Western European nations and the United States. However, since the end of the Cold War, additional countries from the East, such as Turkey, have entered into the NATO alliance.

Besides participating in the UN and NATO, the United States also distributes hundreds of millions of dollars each year in foreign aid to improve the quality of life of citizens in developing countries. The United States may also forgive the foreign debts of these countries. By definition, developing countries are not modernized in terms of infrastructure and social services and thus suffer from instability. Helping them modernize and develop stable governments is intended as a benefit to them and a prop to the stability of the world.

Types of Foreign Policy Goals

The United States pursues its four main foreign policy goals through several different foreign policy types, or distinct substantive areas of foreign policy. These types are trade, diplomacy, sanctions, military/defense, intelligence, foreign aid, and global environmental policy.

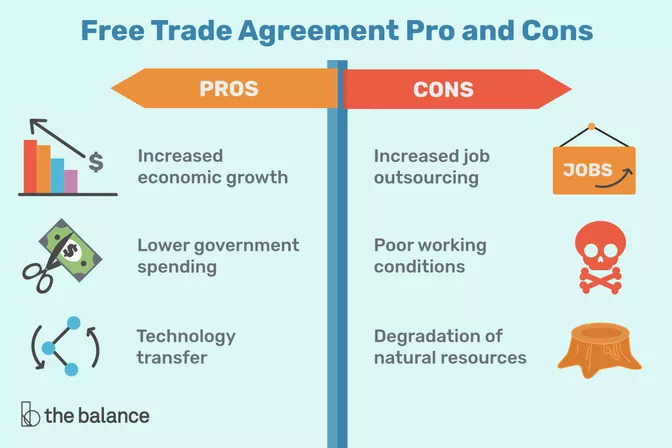

Trade policy is the way countries interact to ease the flow of commerce and goods and services. A country is said to be engaging in protectionism when it does not permit other countries to sell goods and services within its borders, or when it charges very high tariffs (or import taxes) to do so. At the other end of the spectrum is a free trade approach, in which a country allows the unfettered flow of goods and services between itself and other countries. At times the United States has been free trade–oriented, while at other times it has been protectionist. In 1991, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) removed trade barriers and other transaction costs levied on goods moving between the United States, Mexico, and Canada. (NAFTA was replaced by the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) on July 1, 2020.)

Source: The Balance

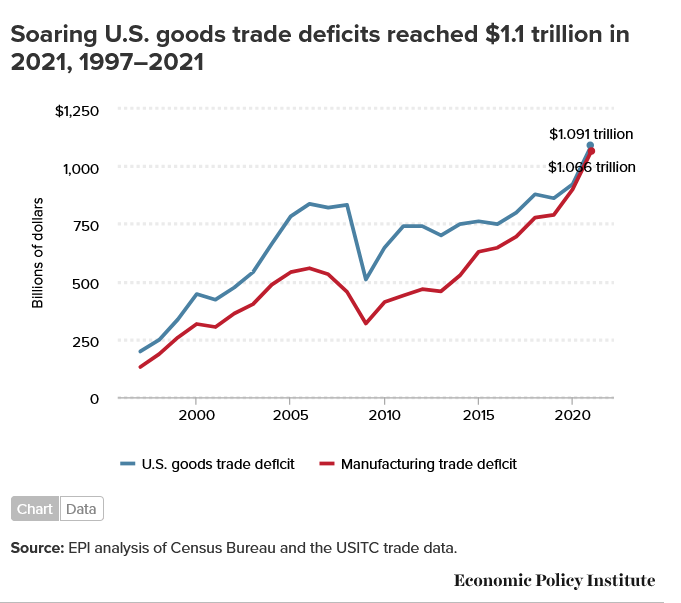

The balance of trade is the relationship between a country’s inflow and outflow of goods. The United States sells many goods and services around the world, but overall it maintains a trade deficit, in which more goods and services are coming in from other countries than are going out to be sold overseas. This trade deficit has led some to advocate for protectionist trade policies.

Source: Economic Policy Institute

Diplomacy is the establishment and maintenance of a formal relationship between countries that governs their interactions on matters as diverse as tourism, the taxation of traded goods, and the landing of planes on each other’s runways. Diplomatic relations are formalized through the sharing of ambassadors (country representatives who live and maintain an office known as an embassy).

To illustrate how international relations play out when countries come into conflict, consider the Hainan Island incident. In 2001, a U.S. spy plane collided with a Chinese jet fighter near Chinese airspace, where U.S. planes were not authorized to be. The Chinese jet fighter crashed and the pilot died. The U.S. plane made an emergency landing on the island of Hainan. China retrieved the aircraft and captured the U.S. pilots. U.S. ambassadors then attempted to negotiate for their return. These negotiations were slow and ended up involving officials of the president’s cabinet, but they ultimately worked. Had they not succeeded, an escalating set of options likely would have included diplomatic sanctions (removal of ambassadors), economic sanctions (such as an embargo on trade and the flow of money between the countries), minor military options (such as establishment of a no-fly zone just outside Chinese airspace), or more significant military options (such as a focused campaign to enter China and get the pilots back). Nonmilitary tools to influence another country, like economic sanctions, are referred to as soft power, while the use of military power is termed hard power.[5]

As a last resort, and when diplomacy fails, the U.S. military may wage war. (Keep in mind, only Congress can officially declare war. However, the president may commit troops as long as Congress is notified of such actions.) Some conflicts are offensive, such as the Iraq War in 2003 and the 1989 removal of Panamanian leader Manuel Noriega. Or it can be defensive, as a means to respond to aggression from others, such as the Persian Gulf War in 1991, also known as Operation Desert Storm.

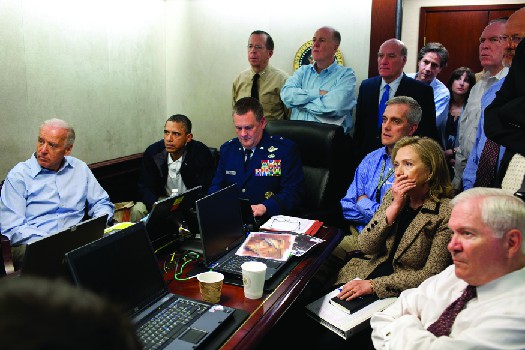

Intelligence policy is related to defense and includes the overt and covert gathering of information from foreign sources that might be of strategic interest to the United States. The intelligence world captures the imagination of the general public. Many books, television shows, and movies entertain us (with varying degrees of accuracy) through stories about U.S. intelligence operations and people.

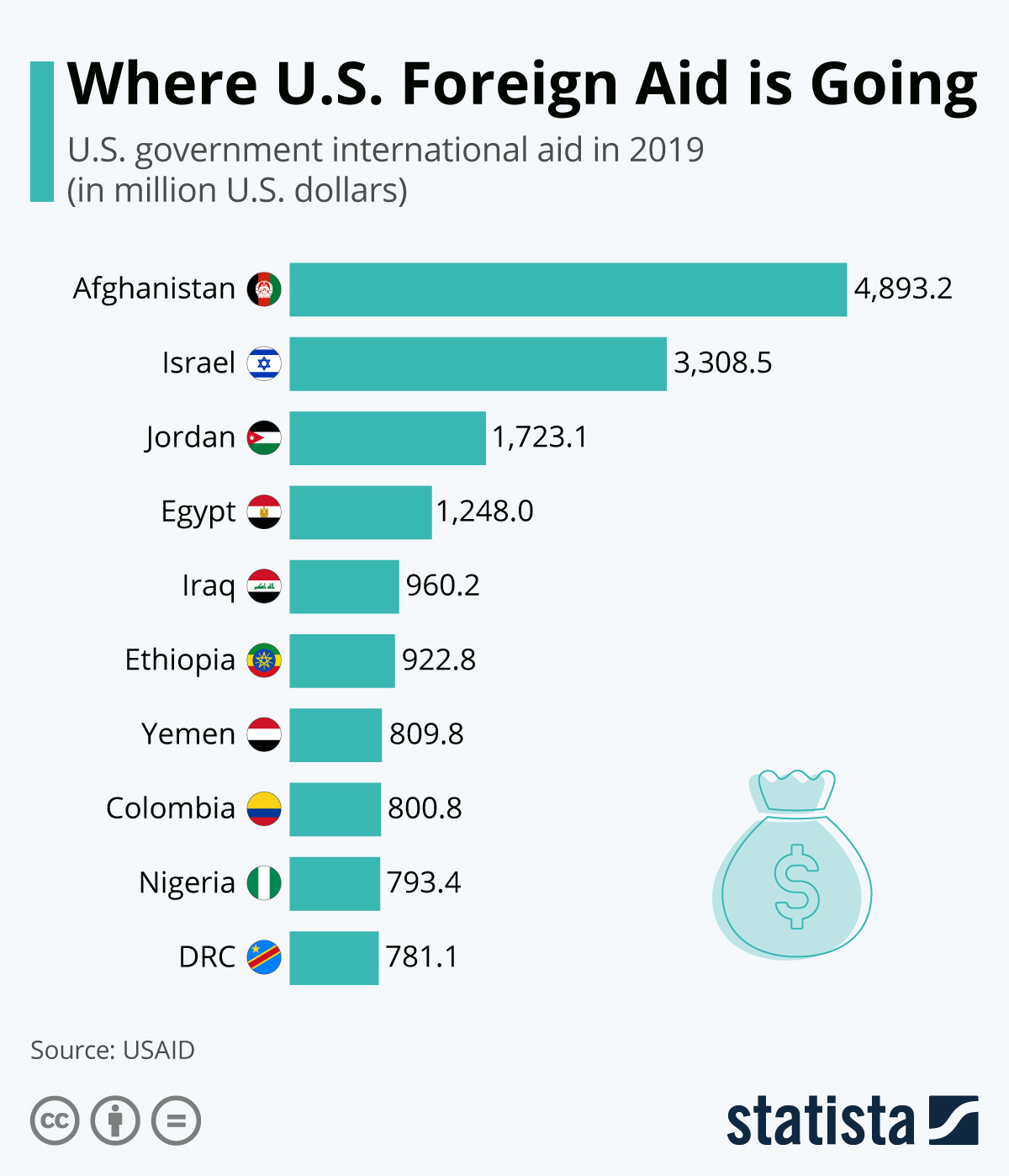

Foreign aid and global environmental policy are the final two foreign policy types. With both, the United States operates as a strategic actor with its own interests in mind, but also acts as an international steward trying to serve the common good. Through foreign aid, the United States provides material and economic aid to other countries, especially developing countries, in order to improve their stability and their citizens’ quality of life. NOTE: This chart shows U.S. foreign aid for 2019. Subsequent years were skewed by the Covid-19 Pandemic.

Source: Statista

Global environmental policy addresses world-level matters, such as climate change and global warming, the thinning of the ozone layer, rainforest depletion in areas along the Equator, and ocean pollution and species extinction. The United States’ commitment to such issues has varied considerably over the years. For example, the United States was the largest country not to sign the 1997 Kyoto Protocol on greenhouse gas emissions. However, it does support the Paris Accords, an international treaty on climate change adopted in 2015.

Unique Challenges in Foreign Policy

U.S. foreign policy is a massive and complex enterprise. What are its unique challenges for the country?

First, there exists no true world-level authority dictating how the nations of the world should relate to one another. If one nation negotiates in bad faith or lies to another, there is no central world-level government authority to sanction that country. Foreign relations are certainly made smoother by the existence of cross-national voluntary associations like the United Nations, the Organization of American States, and the African Union. However, these associations do not have strict enforcement authority over specific nations, unless a group of member nations takes action in some manner (which is ultimately voluntary).

The European Union is the single supranational entity with some real and significant authority over its member nations. Adoption of its common currency, the euro, brings with it concessions from countries on a variety of matters, and the EU’s economic and environmental regulations are the strictest in the world. Yet even the EU has enforcement issues, as evidenced by the battle within its ranks to force member Greece to reduce its national debt or the recurring problem of Spain overfishing in the North Atlantic Ocean. The withdrawal of the United Kingdom (commonly referred to as Brexit, short for British exit) also points to its struggles.

International relations take place in a relatively open venue. When does it make sense to sign a multinational pact and when doesn’t it? Is a particular bilateral economic agreement truly as beneficial to the United States as to the other party? These are open and complicated questions.

A second challenge is the widely differing views among countries about the role of government in people’s lives. The hardline communist North Korean government regulates everything in its people’s lives every day. At the other end of the spectrum are countries with little government activity at all, such as parts of the island of New Guinea. In between is a vast array of diverse approaches to governance. Countries like Sweden provide cradle-to-grave human services programs such as health care and education that in some parts of India are minimal at best. In Egypt, the nonprofit sector provides many services rather than the government. The United States falls somewhere in the middle of this continuum because of its focus on law and order, educational and training services, and old-age pensions and health care in the form of Social Security and Medicare.

Thirdly, countries have varying ideas about the appropriate form of government, ranging from democracies on one side to various authoritarian (or nondemocratic) forms on the other. Relations between the United States and democratic states tend to operate more smoothly, based on a shared core assumption that the government’s authority comes from the people. Monarchies and other nondemocratic forms of government do not share this assumption, which can complicate foreign policy discussions immensely. People in the United States often assume that people who live in a nondemocratic country would prefer to live in a democratic one. However, in some regions of the world, people often prefer having stability within a nondemocratic system over changing to a less predictable democratic form of government. Or they may just believe in a theocratic form of government.

A fourth challenge is that many new foreign policy issues transcend borders. There are no longer simply friendly states and enemy states. Terrorism, the international slave trade, and climate change originate with groups and issues that are not country-specific. They are transnational. For example, while we can readily name the enemies of the Allied forces in World War II (Germany, Italy, and Japan), the U.S. war against terrorism has been aimed at terrorist groups that do not fit neatly within the borders of any one country. Intelligence-gathering and focused military intervention is needed more than traditional diplomatic relations, and relations can become complicated when the United States wants to pursue terrorists within other countries’ borders.

The fifth and final unique challenge is the varying conditions of the countries in the world and their effect on what is possible in terms of foreign policy and diplomatic relations. Relations between the United States and a stable industrial democracy are going to be easier than between the United States and an unstable developing country being run by a military junta (a group that has taken control of the government by force). Moreover, an unstable country will be more focused on establishing internal stability than on broader world concerns like environmental policy. In fact, developing countries are temporarily exempt from the requirements of certain treaties while they seek to develop stable industrial and governmental frameworks.

Summary

As the president, Congress, and others carry out U.S. foreign policy in the areas of trade, diplomacy, defense, intelligence, foreign aid, and global environmental policy, they pursue a variety of objectives and face a multitude of challenges. The four main objectives of U.S. foreign policy are the protection of the United States and its citizens and allies, the assurance of continuing access to international resources and markets, the preservation of a balance of power in the world, and the protection of human rights and democracy.

The challenges of the massive and complex enterprise of U.S. foreign policy are many. First, there exists no true world-level authority dictating how the nations of the world should relate to one another. A second challenge is the widely differing views among countries about the role of government in people’s lives. A third is other countries’ varying ideas about the appropriate form of government. A fourth challenge is that many new foreign policy issues transcend borders. Finally, the varying conditions of the countries in the world affect what is possible in foreign policy and diplomatic relations.

Connecting Chapters

- What are two key differences between domestic policymaking and foreign policymaking?

Resources

- Eugene R. Wittkopf, Christopher M. Jones, and Charles W. Kegley, Jr. 2007. American Foreign Policy: Pattern and Process, 7th ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. ↵

- Michelle Camacho Liu. 2011. Investing in Higher Education for Latinos: Trends in Latino College Access and Success. Washington, DC: National Conference of State Legislatures. http://www.ncsl.org/documents/educ/trendsinlatinosuccess.pdf (May 12, 2016). ↵

- Charlene Barshefsky and James T. Hill. 2008. U.S.–Latin America Relations: A New Direction for a New Reality. Washington, DC: Council on Foreign Relations. i.cfr.org/content/publications/attachments/LatinAmerica_TF.pdf (May 12, 2016). ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau, "Foreign Trade: U.S. International Trade Data" https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/data/index.html (May 12, 2016). ↵

- Joseph S. Nye, Jr. 2005. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. Washington, DC: Public Affairs. ↵

- U.S. Agency for International Development, "U.S. Overseas Loans and Grants (Greenbook)," https://explorer.usaid.gov/reports-greenbook.html (June 18, 2016); C. Eugene Emery Jr., and Amy Sherman. 2016. "Marco Rubio says foreign aid is less than 1 percent of federal budget," Politifact, 11 March 2016. http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2016/mar/11/marco-rubio/marco-rubio-says-foreign-aid-less-1-percent-federa/. ↵

- American Government 2e. Authored by: OpenStax. Located at: https://cnx.org/contents/nY32AU8S@5.1:xJJkKaSK@5/Preface. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/9d8df601-4f1...50bf739e5f@5.1