1.7: Sub-Disciplines of Geography

- Page ID

- 131867

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Geography has two primary branches, physical and human geography, but numerous sub-disciplines. Furthermore, as with world regions, it’s often difficult to make precise boundaries between fields of study. A geographer might be a human geographer who specializes in culture who further specializes in religion. That same geographer might also conduct side research on environmental issues. And she might, in her spare time, investigate geographies of fictional landscapes. Everything happens somewhere, and thus everything is geographical.

Within physical geography, the main sub-disciplines are:

- biogeography (the study of the spatial distribution of plants and animals),

- climatology (the study of climate),

- hydrology (the study of water), and

- geomorphology (the study of Earth’s topographic features).

This list is not inclusive. Some geographers study geodesy, the scientific measurement and representation of Earth. Others study pedology, the exploration of soils. What unites physical geographers is an emphasis on the scientific study of the physical features of Earth in all of its many forms.

Human geography consists of a number of sub-disciplines that often overlap and interact. The main sub-disciplines of human geography include:

- cultural geography (the study of the spatial dimension of culture),

- economic geography (the study of the distribution and spatial organization of economic systems),

- medical geography (the study of the spatial distribution of health and medicine),

- political geography (the study of the spatial dimension of political processes),

- population geography (also known as demography, the study of the characteristics of human populations),

- and urban geography (the study of urban systems and landscapes).

Human geographers essentially explore how humans interact with and affect the earth.

Political geography provides the foundation for investigating what many people understand as geography: countries and governmental structures. Political geographers ask questions like “Why does a particular state have a conflict with its neighbor?” and “How does the government of a country affect its voting patterns?” When political geographers study the world, they refer to states, which are independent, or sovereign, political entities recognized by the international community. States are commonly called “countries” in the United States. For example, Germany, France, China, and South Africa are all “states.”

So how many states are there in the world? The question is not as easy to answer as it might seem. What if a state declares itself independent, but is not recognized by the entirety of the international community? What if a state collaborates so closely with its neighbor that it gives up some of its sovereignty? What happens if a state is taken over by another state? As of 2019, there are 206 states that could be considered sovereign, though some are disputed and are only recognized by one other country. Only 193 states are members of the United Nations. Others, like Palestine, are characterized as “observer states.” The United States Department of State recognizes 195 states as independent, including the Holy See, often known as Vatican City, and Kosovo, a disputed state in Southeastern Europe.

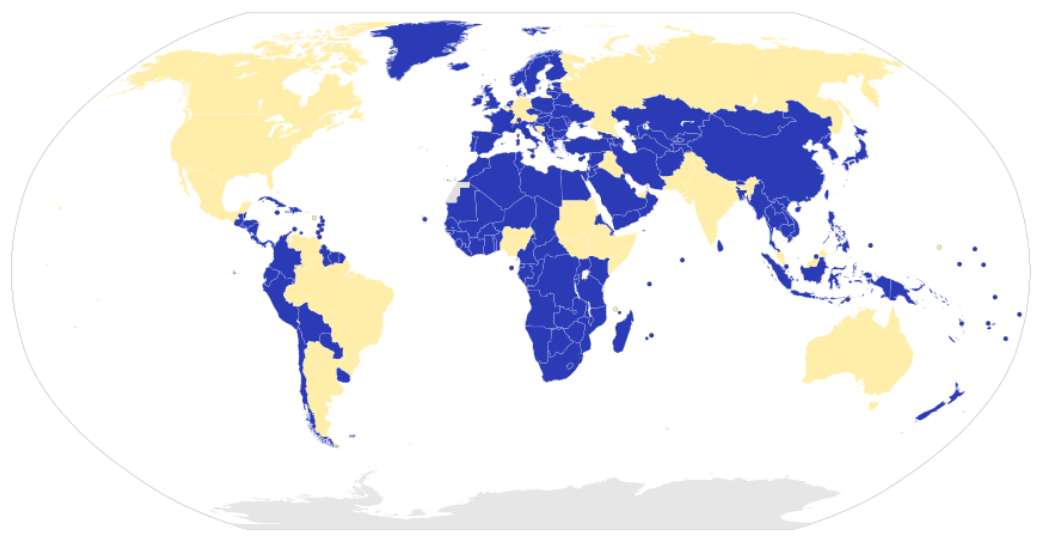

In addition to questions of sovereignty, political geographers investigate the various forms of government found around the world (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). States govern themselves in a variety of ways, but the two main types of government are unitary and federal. In a unitary state, the central government has the most power. Local or regional governments might have some decision-making power, but only at the command of the central government. Most of the states of the world have unitary systems. A federal state, on the other hand, has numerous regional governments or self-governing states in addition to a national government. Several large states like the United States, Russia, and Brazil are federations.

Economic geographers explore the spatial distribution of economic activities. Why are certain states wealthier than others? Why are there regional differences related to economic development within a country? All countries have some sort of economic system but have different resources, styles of development, and government regulations. So how can we compare countries in terms of economic development? One way is by examining a country’s gross domestic product (GDP), the value of all the goods and services produced in a country in a given year. Often, it is helpful to divide GDP by the number of people in a country; this is known as GDP per capita and it roughly equates to average income. However, goods have different costs in different countries, so GDP per capita is generally given in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP), meaning that each country’s currency is adjusted so that it has roughly the same purchasing power. Thus, GDP per capita in terms of PPP simply refers to the amount of goods and services produced in a country divided by the number of people in that country and then adjusted for how much goods and services actually cost in that country.

One limitation of GDP is that it only takes into account the goods and services produced domestically. However, many businesses today have locations and production facilities in other countries. Gross National Income (GNI) is a way to measure a country’s economic activity that includes all the goods and services produced in a country (GDP) as well as income received from overseas.

- States:

-

an independent and sovereign political entity recognized by the international community

- Unitary State:

-

a political system characterized by a powerful central government

- Federal State:

-

a political system characterized by regional governments or self-governing states

- Gross Domestic Product:

-

the value of all the goods and services produced in a country in a given year

- Gross National Income:

-

the value of all the goods and services produced in a country in a given year and the income received from overseas