10.2: Piaget preoperational stage

- Page ID

- 180266

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Piaget’s stage that coincides with early childhood is the preoperational stage. The word operational means logical or able to carry out mental operations, so these children were thought to be illogical. However, they were learning to use language or to think of the world symbolically. Let’s examine some of Piaget’s assertions about children’s cognitive abilities at this age.

Pretend Play

According to Piaget, the main characteristic of sensorimotor stage is that children are unable to use symbolic representation in their thinking. Once they are able to use symbols in their thought they are considered preoperational. In the preoperational stage, pretending is a favorite activity. A toy has qualities beyond the way it was designed to function and can now be used to stand for a character or object unlike anything originally intended. A teddy bear, for example, can be a baby or the queen of a faraway land!

According to Piaget, children’s pretend play helps them solidify new schemes they were developing cognitively. This play, then, reflects changes in their conceptions or thoughts. However, children also learn as they pretend and experiment. Their play does not simply represent what they have learned (Berk, 2007).

Egocentrism

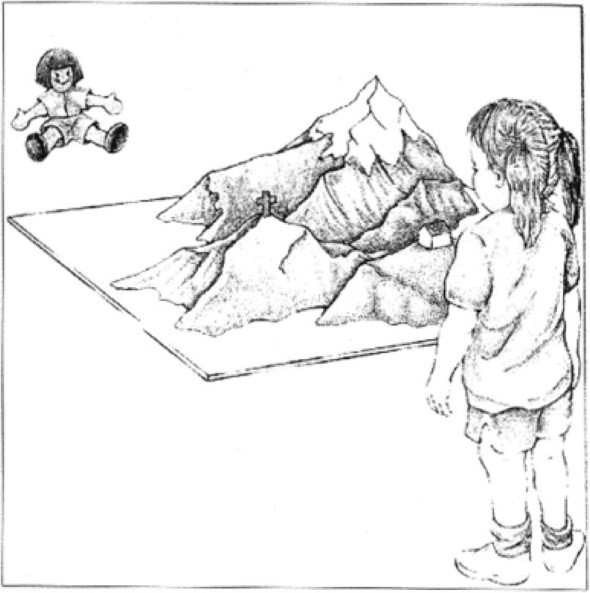

Egocentrism in early childhood refers to the tendency of young children to think that everyone sees things in the same way as the child. Piaget’s classic experiment on egocentrism involved showing children a 3-dimensional model of a mountain and asking them to describe what a doll that is looking at the mountain from a different angle might see. Children tend to choose a picture that represents their own view, rather than that of the doll.

However, children tend to use different sentence structures and vocabulary when addressing a younger child or an older adult. This indicates some awareness of the views of others.

Syncretism

Syncretism refers to a tendency to think that if two events occur simultaneously, one caused the other. An example of this is a child putting on their bathing suit to turn it to summertime.

Animism

Attributing lifelike qualities to objects is referred to as animism. The cup is alive, the chair that falls down and hits the child’s ankle is mean, and the toys need to stay home because they are tired. Cartoons frequently show objects that appear alive and take on lifelike qualities. Young children do seem to think that objects that move may be alive but after age 3, they seldom refer to objects as being alive (Berk, 2007).

Classification Errors

Preoperational children have difficulty understanding that an object can be classified in more than one way. For example, if shown three white buttons and four black buttons and asked whether there are more black buttons or buttons, the child is likely to respond that there are more black buttons. As the child’s vocabulary improves and more schemes are developed, the ability to classify objects improves.[3]

Conservation Errors

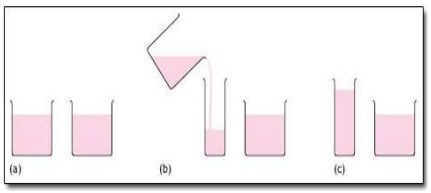

Conservation refers to the ability to recognize that moving or rearranging matter does not change the quantity. Let’s look at an example. A father gave a slice of pizza to 10-year-old Keiko and another slice to 3-year-old Kenny. Kenny’s pizza slice was cut into five pieces, so Kenny told his sister that he got more pizza than she did. Kenny did not understand that cutting the pizza into smaller pieces did not increase the overall amount. This was because Kenny exhibited Centration, or focused on only one characteristic of an object to the exclusion of others.

Kenny focused on the five pieces of pizza to his sister’s one piece even though the total amount was the same. Keiko was able to consider several characteristics of an object than just one. Because children have not developed this understanding of conservation, they cannot perform mental operations.

Evaluating the preoperational stage

Similar to the critique of the sensorimotor period, several psychologists have attempted to show that Piaget also underestimated the intellectual capabilities of the preoperational child. For example, children’s specific experiences can influence when they are able to conserve. Children of pottery makers in Mexican villages know that reshaping clay does not change the amount of clay at much younger ages than children who do not have similar experiences (Price-Williams et al, 1969). Crain (2005) indicated that preoperational children can think rationally on mathematical and scientific tasks, and they are not as egocentric as Piaget implied.13 Research on Theory of Mind (discussed later in the chapter) has demonstrated that children overcome egocentrism by 4 or 5 years of age, which is sooner than Piaget indicated.

Both Piaget and Vygotsky believed that children actively try to understand the world around them. More recently, developmentalists have added to this understanding by examining how children organize information and develop their own theories about the world.

Theory of mind refers to the ability to think about other people’s thoughts. This mental mind reading helps humans to understand and predict the reactions of others, thus playing a crucial role in social development. One common method for determining if a child has reached this mental milestone is the false belief task, described below.

The research began with a clever experiment by Wimmer and Perner (1983), who tested whether children can pass a false-belief test.14 The child is shown a picture story of Sally, who puts her ball in a basket and leaves the room. While Sally is out of the room, Anne comes along and takes the ball from the basket and puts it inside a box. The child is then asked where Sally thinks the ball is located when she comes back to the room. Is she going to look first in the box or in the basket? The right answer is that she will look in the basket, because that’s where she put it and thinks it is; but we have to infer this false belief against our own better knowledge that the ball is in the box. This is very difficult for children before the age of four because of the cognitive effort it takes. Three- year-olds have difficulty distinguishing between what they once thought was true and what they now know to be true. They feel confident that what they know now is what they have always known (Birch and Bloom, 2003).

Even adults need to think through this task (Epley et al, 2004) To be successful at solving this type of task the child must separate what he or she “knows” to be true from what someone else might “think” is true. In Piagetian terms, they must give up a tendency toward egocentrism. The child must also understand that what guides people’s actions and responses are what they “believe” rather than what is reality. In other words, people can mistakenly believe things that are false and will act based on this false knowledge. Consequently, prior to age four children are rarely successful at solving such a task (Wellman et al, 2001). But this is quite different from Piaget’s ideas that a child remains in the preoperational stage from 2 until 7 years old!

References:

Birch, S., & Bloom, P. (2003). Children are cursed: An asymmetric bias in mental-state attribution. Psychological Science, 14(3), 283-286.

Crain, W. (2005). Theories of development concepts and applications (5th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson.

Epley, N., Morewedge, C. K., & Keysar, B. (2004). Perspective taking in children and adults: Equivalent egocentrism but differential correction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 760–768.

Price-Williams, R., Gordon, W., & Ramirez, M. (1969). Skill and conservation: A study of pottery making children.Developmental Psychology, 1, 769.

Wellman, M., Cross, D., & Watson, J. (2001). Meta-analysis of theory of mind development: The truth about false belief. Child Development, 72(3), 655-684.

Wimmer, , & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition, 13, 103–128.

Attributions:

Child Growth and Development by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Rymond, 2019, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[1] Image by Ermalfaro is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

[2] Image by Rosenfeld Media is licensed under CC BY 2.0

[3] Lifespan Development - Module 5: Early Childhood by Lumen Learning references Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology by Laura Overstreet, licensed under CC BY 4.0

[4] Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

[5] Image by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0